On September 25, Italians will be called to elect a new Parliament. The snap election follows on the heels of the collapse of the government in late July and the resignation of former European Central Bank (ECB) President Mario Draghi. That the country would dismiss such an esteemed prime minister and hold early elections—while it remains lashed by the interconnected crises of Covid-19, the rise in energy prices, and an impending recession—has been a cause of consternation and confusion for many in the international press.

From the outside, Italian politics appears mystifying and convoluted. In reality, it is quite predictable: Patterns that occurred in previous decades reemerge and repeat themselves in a cyclical manner. For the past thirty years, Italy’s perpetual state of emergency has periodically necessitated the formation of expert-led national-emergency governments. In subsequent elections, disappointed voters shift their allegiance to individuals and organizations that can credibly present themselves as an alternative to the status quo. All the while, a new existential threat on the horizon compels the remaining “responsible” forces to empower a new cohort of technocrats.

Marx warned that history repeats itself—first as tragedy, then as farce—but he never elaborated what might come next. Perhaps more germane to the Italian situation is a paraphrase of Nietzsche: Italian politics is the eternal return of the same. In Italy, this pattern is accompanied by a long-term economic decline encompassing stagnating growth and labor productivity, and increasingly precarious jobs. The homines novi (or, more accurately, mulieres novae) who are called upon to save the country are becoming increasingly worrying.

As the new secretary of the Partito Democratico (PD), Matteo Renzi benefited from an aura of novelty in the European elections of 2014. The same can be said of the Movimento Cinque Stelle (M5S) when it rose to prominence in 2013—and again in 2018. Both parties lost much of their appeal after their involvement in government produced paltry results, proving themselves unable to halt economic stagnation. Now, with fresh elections to take place later this month, it will be the turn of Giorgia Meloni, leader of the post-fascist Fratelli d’Italia (FdI), to capitalize on the allure of newness. Having remained in opposition to recent governments, especially Draghi’s, she has some claim to outsider status (never mind her and her rumored future cabinet members’ positions in Silvio Berlusconi’s 2008–2011 government). Polls anticipate an avalanche of votes putting her in pole position to lead the next government.

The economic crisis

Once a model of economic development, Italy’s economic growth has been considerably slower than that of other OECD nations since the mid-1990s. There is no consensus among academics regarding the causes of the country’s economic stagnation. Mainstream Italian economists contend that the country’s woes are due to insufficient liberalization reforms, but in fact Italy has introduced more liberalization than many of its European neighbors. In some cases, these reforms have achieved the opposite of their intended goals. For instance, the labor-market liberalization enacted since 1996 has facilitated the creation of low-skill or low-value-added jobs and led to the simultaneous spread of precarious employment and stagnant labor productivity.

An alternative explanation attributes Italy’s stagnation to the country’s botched integration into the European Monetary Union (EMU). Prior to the financial crisis, the EMU economic architecture allowed two types of growth models: export-led and debt-led growth. The former, exemplified by Germany, was based on a real exchange rate devaluation that stimulated exports and a real wage moderation that depressed domestic demand. The latter model, epitomized by Spain and pre-crisis Ireland, was based on credit creation that fueled a construction boom, which had positive knock-on effects for domestic demand but resulted in substantial current account deficits, financed through capital imports from central and northern European countries. Italy failed to capitalize on either growth driver. Because the Italian export sector is too small to carry the economy on its shoulders, an export-led growth model was unrealistic. And given Italy’s tendency to produce higher inflation than its trading partners within the eurozone and the price sensitivity of its exports, real appreciation penalized Italian exports and made imports cheaper. Furthermore, with extremely high levels of public debt as a proportion of GDP, the primary fiscal balance had to remain in surplus, particularly in the late 1990s. The need to keep government accounts in check made an expansion of domestic demand improbable.

In the late 2000s to the early 2010s, the country was hit by two shocks in short succession. First, the global financial crisis led to a drastic contraction in demand, to which the government responded with an insufficient fiscal expansion. Then, just a few years later, Italy felt the brunt of the sovereign debt crisis. Although there was no requirement to negotiate a bailout program with the troika, it voluntarily introduced austerity measures (expenditure cuts and taxation increases) as well as structural reforms to regain the confidence of international bond markets. Consequently, the economy fell into a double-dip recession and was unable to recover to pre-crisis GDP levels.

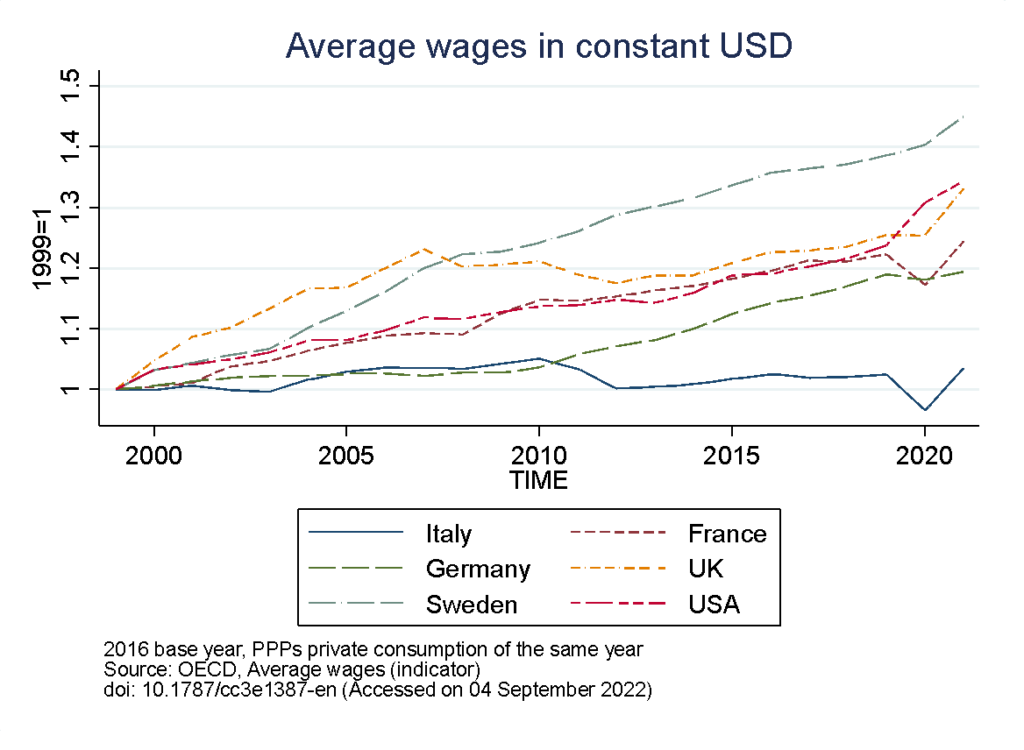

Then came a third shock: the Covid-19 pandemic. This, too, resulted in a sharp decrease in aggregate demand. This time the government did respond with more robust budgetary expansion, which the EU authorities allowed. Opting for a very different approach to previous crises, it authorized the issuance of shared debt to assist the member states most severely impacted by the pandemic, among them Italy. However, this was not enough to mitigate the effects of the previous crises. Between 1999 and 2020, Italy’s real wages did not increase at all (see graph). External constraints, especially the need to remain a member of the eurozone, governed Italy’s most important policy decisions at critical junctures.

The political response

In recent years, Italy’s politics have been characterized by a peculiar combination of technocracy and anti-elite populism. The reliance on technocratic solutions began with the crisis of the early 1990s, when Italy’s attempt to rigidly fix its nominal exchange rate within the European Monetary System (EMS), the precursor to the euro, led to a competitiveness crisis. This in turn was followed by a confidence crisis, which resulted in the Lira’s expulsion from the EMS. The outcome was not unpredictable for a country with a higher inflation rate than its exchange-rate partners, and therefore subject to real exchange-rate erosion. Not to be discouraged, only three years later, the Italian government decided to double down and enter an even more rigid exchange-rate mechanism: the euro. Within the confines of the euro, the possibility of nominal exchange rate adjustment was completely eliminated.

Italy’s mode of crisis management was established in the early 1990s. In the midst of the Mani Pulite wave of corruption scandals, a government of unelected experts—led by the Bank of Italy’s former president Carlo Azeglio Ciampi—was installed. It had almost unanimous support from all parties, particularly from the center-left. Its task was to do the dirty work that the parties were unwilling to do: institutionalized wage moderation, expenditure cuts, tax increases, structural reforms. The government collapsed after little more than a year, but it had created the pattern that would be repeated for years to come.

At the end of 2011, the political response to the euro crisis followed suit. At the time, the yield on Italy’s treasury bonds was reaching unmanageable levels, threatening a default or a bailout package. Mario Monti, a professor of economics and former European commissioner for competition, was hastily chosen as prime minister of a new technocratic government to replace the discredited Berlusconi government. Its main goal was to regain the confidence of international financial markets by implementing policies similar to those imposed by the troika on “program countries,” i.e. business-friendly structural reforms, budget consolidation, and the destruction of domestic demand to produce a current account surplus. Unsurprisingly, the remedy threw the nation into a deep recession, and the proportion of debt to GDP grew even further. Nonetheless, the objective of preserving Italy’s participation in the euro was attained.

In Italy, technocracy and anti-elite populism are deeply entwined. At critical junctures, when the nation allegedly faces an existential threat, experts are called in to save the day; armed with technical expertise, they claim to understand what it takes to turn around the economy. They impose measures like budget consolidation and structural reforms, which they see as necessary despite their unpopularity. Not being accountable to voters as a political party would be, their task is to simply administer the bitter medicine. Then comes disappointment, as the measures fail to rekindle growth. This failure, however, is not attributed to a misdiagnosis of the problem. Rather, it is society’s stubborn resistance to structural reform that is blamed. In other words, the cure was right, but the patient did not take the prescribed medication, and the dose was insufficient. At the next election, the “responsible” forces that supported technocratic administrations are punished, while the Italian voter swings towards actors that can credibly claim they are not compromised by the status quo, and therefore have the ability to turn things around.

The winner of the 2013 election, following the Monti administration, was the M5S, whose vote share grew from 0 to 25.5 percent. The young party promised to “open the parliament like a can of tuna fish.” Lacking the votes to form a government, the Movimento remained in opposition. The social-democratic Partito Democratico (PD), heir of the Italian Communist Party, was the dominant party in government during the 2013–2018 legislature, despite performing far worse at the ballot box than predicted by pre-election polls. The PD has evolved into the party of government par excellence. Since 2011, it has participated in every government except one.

The most recent legislature was more of the same. The M5S won the election of 2018 with almost 33 percent of the vote. In a bid to safeguard Italy’s membership in the euro, which was thought to be threatened by anti-system forces like the M5S and the Lega, President of the Republic Sergio Mattarella sought to cobble together another technocratic government, but failed. Eventually, M5S and the Lega formed a joint government led by Giuseppe Conte, a law professor with no previous political experience. This green-yellow executive passed measures to alleviate poverty (citizenship income) and combat precarious employment (decreto dignità), at the same time as it passed anti-immigrant policy (decreti sicurezza) and made an unsuccessful attempt to flout EU budget rules to engineer a fiscal expansion. The Lega pulled the plug on the government in the summer of 2019—likely to avoid having to sign a budget law that would reduce the public deficit. It also hoped to capitalize on its significant surge in opinion polls in the event of early elections. At the time of the government crisis, the Lega polled well above 30 percent, up from 17 percent in the 2018 legislative elections.

However, there were no early elections, and a new coalition M5S–PD government led by Conte was created. Starting in February 2020, the government’s first goal was to address the massive health and economic crisis caused by Covid-19, which struck Italy earlier and more harshly than other European countries. The Conte administration was a strong advocate for a unified European approach to the crisis and requested the creation of common European debt. Despite initial reluctance, the German government eventually agreed to this proposal, which led to the introduction of NextGenEU, from which Italy benefited disproportionately by receiving €69 billion in grants and €123 billion in loans to invest in digitalization, healthcare, and the green transition.

The life of the second Conte government was cut short by internecine conflict over the management of both the Covid-19 crisis and NextGenEU. This resulted in the formation of yet another technocratic government of national unity, led by Italy’s most prestigious international public servant, former ECB president Mario Draghi. All parties joined the new governing coalition—but for Giorgia Meloni’s Fratelli d’Italia. In refusing participation, Meloni saved her party from the voter discontent that plagued the others. What precipitated the collapse of the Conte government remains unclear, but it cannot be excluded that a new government was required to prevent the M5S, the largest party in parliament, with a strong electoral base in the Mezzogiorno, from managing the allocation and distribution of European funds to benefit its southern constituency. Over the last thirty years, the South has experienced an economic decline even more pronounced than the rest of the country, and the state has ceased any efforts to close the gap. Since one of the objectives of the European funds is to reduce regional disparities, the money should indeed have been largely allocated to the southern regions. But this would have harmed the richer northern regions, the backbone of Italy’s productive system.

The Draghi government was in office between February 2021 and July 2022. During this period, the M5S steadily lost support—hardly a surprise for a party that pitched itself as an alternative to every other party yet ended up ruling with practically all of them, with mediocre results—as did the Lega. Electoral support for the PD, by contrast, remained stable at 20–22 percent. While the PD benefited little from the M5S’s decline, support for FdI soared to about 25 percent of the vote, becoming the leading party in Italy.

The legislature was due to expire in early 2023, with elections to be held in the spring. Its term was foreshortened, however, as the M5S grew increasingly uneasy about backing a government that appeared determined to weaken or reverse a number of its signature policies (such as the citizenship income). In turn, Forza Italia and the Lega wanted a new government that would exclude M5S. Even Mario Draghi seemed unenthusiastic about the prospect of guiding a government through the numerous interconnected emergencies on the horizon—among them continuing support for the war in Ukraine, the energy crisis, rising inflation, the tightening of monetary policy, and possibly a new sovereign bond crisis. Interestingly, the M5S itself was split about whether or not to support the Draghi government, and a substantial number of parliamentarians, who had previously pledged to turn the Italian political system inside out, joined the ranks of the responsible forces backing the government. The government fell nonetheless.

The limits of change

With fresh elections on the horizon, front runner Giorgia Meloni is well-positioned to head the next executive. What kinds of changes might we anticipate? Meloni has made it abundantly clear that she wishes to avoid any confrontation with the European Union over budget issues, and she is staunchly on the side of NATO with regard to Italy’s participation in the Ukraine conflict. In terms of economic policy, any new Italian government will have little room for maneuver. Although the Stability and Growth Pact is suspended until 2023 (due to both the pandemic and war), Italy’s involvement in the NextGenEU severely restricts any future expenditure decisions, be it in terms of their nature, amount, or timing. In addition, for a high-debt, low-growth country like Italy, it is crucial that the ECB be prepared to intervene in bond markets as a buyer of last resort. It is prepared to perform this role with the adoption of the Transmission Protection instrument (TPI) in July 2022, but will do so only if the Italian government adheres to the European fiscal rules and honors the commitments of the NextGenEU.

In 2013, Mario Draghi, then President of the ECB, stated that Italy’s economic policy was “independent of election results” and running “on autopilot.” It’s a statement that is even more accurate now. Italy’s economic policy will continue to be guided by external constraints. However, the shift in government will not be without consequence, and two groups in particular—migrants and the poor—will likely bear the brunt of any changes. Under a Meloni-led government, it will be more difficult for new migrants to reach Italy’s coasts. We may see a repeat of 2018–2019, when refugee-filled vessels were kept anchored outside of ports and denied entry. Existing migrants’ rights, such as access to social services, may also be restricted. This will please the highly anti-immigrant electoral base of the right.

Beneficiaries of the citizenship income, a sort of basic income, will be the second group to be targeted. According to Italy’s statistical agency ISTAT, one million individuals were lifted out of poverty by the citizenship income in 2020 at a cost of 7.2 billion euros (corresponding to less than 0.5 of GDP). The right holds the citizenship income accountable for the labor shortage that hotels and restaurants experienced last summer. They have pledged to eliminate the citizenship income and reallocate the meager proceeds to one of the right’s primary constituencies: the self-employed and small-business owners. Other initiatives, such as the proposals for a flat tax, are too costly for the incoming government to contemplate without factoring in a tough fight with the EU over budget overshoots.

To be sure, the measures one can realistically expect from a new right-wing government are unlikely to reverse Italy’s ongoing economic crisis. Beyond September 25, one can expect the cycle of stagnation, emergency, national solidarity governments, and the populist backlash to continue. All this signals the further disintegration of Italy’s existing party system in the years to come.

Filed Under