When Americans ran short on baby food last year, President Joe Biden made use of a Korean War-era authority—the Defense Production Act (DPA)—to airlift goat milk from Australia, despite protectionist howls from American formula companies. Operation Fly Formula funded the passage of 27 million powdered milk tins of Bubs Australia to American babies. If that makes you wonder whether the same authority could be used to get the critical minerals needed for the energy transition, then you might just be a Polycrisis reader.

At the G7 summit in Hiroshima last week, Biden met Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese. Together, they set out to answer a crucial question: is it possible for a country to have China as its largest trading partner, but the US as its security ally? The pair signed a wide-ranging compact that could see American taxpayers support—as buyers, matchmakers, and financiers—Australian mineral projects under the DPA. Details will be fleshed out by the US National Security Council and Australian Department for Industry. If approved by Congress, which looks likely, Australia will be counted as a “domestic” territory of the US under DPA’s key Title 3 on strategic industrial policy. Currently, only foreign companies with mines operating inside the US or Canada can obtain DPA investment.

Approval of the compact would help solve a major problem facing the US and the G7. Clean energy components like electric vehicle (EV) batteries require minerals like lithium and nickel. But reserves in both the US and Europe are either scarce or extraction is held up by concerns over pollution and indigenous land rights. Australia mines more than half of the world’s lithium and virtually all of it goes to China for processing. The West wants that dependence to change. Australia and Canada, both US allies with significant reserves of most transition minerals, and with powerful local mining constituencies, are stepping up for G7 “friendshoring.”

In addition to lithium, Australia has substantial reserves of nickel and cobalt, also used for making EV batteries, as well as copper, used for making, well, everything electric. Days after the G7, Australian trade minister Don Farrell was euphoric, following a Detroit meeting with US secretary of commerce Gina Raimondo. He spoke of a “golden age” of mining to come.

Farrell was in Detroit for talks on the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework: a quasi-trade agreement that the US is developing with thirteen countries, to coordinate supply chains. Ministers from another transition minerals powerhouse, Indonesia, were also in attendance. But DPA deals were not forthcoming, even though economic affairs minister Airlangga Hartarto said his country was ready to supply the US with its domestically made EV batteries.

Both Australia and Indonesia have to balance their relationship with China, their biggest export customer, with the allure of US markets and the new subsidies on offer there. Mineral resources—iron, gas, lithium, copper—form the bulk of Australia’s $180-billion-a-year exports to China; more than half of Indonesia’s sales to China are ores and metals. A call for an investigation into the origins of Covid-19 led to China effectively banning Australian coal, timber, lobster, wine, and barley. The impact was muted as other markets filled some of the gap, but the lifting of restrictions this year was welcomed by smaller sectors.

Appeal to the base

Australia has long enjoyed a security treaty with the US, a relationship it is now making use of to advance its own interests. Last December, Australian foreign minister Penny Wong, a veteran of the center-left Labor Party, which returned to power in 2022, delivered a speech in Washington addressing the rising tensions between the US and China. Countries shouldn’t be required to pick a side in the great power rivalry, she argued. Respecting the agency of nations in the Asia Pacific region meant recognizing their close economic ties with China. For Pacific Island countries, it meant taking seriously the problems of debt, development finance, and “their most profound concern: climate change.”

Wong’s support for regional agency and non-alignment put Australian rhetoric at some distance from the New Washington Consensus espoused by the US administration, which has so far offered little to developing countries. Domestically, she hewed closer to Jake Sullivan and his colleagues’ “foreign policy for the middle class” framing: Australia would be “creating] domestic economic resilience, addressing climate change and energy security through more robust supply chains, making more things in Australia, and skilling our people.”

For a long time now, making things has not been the Australian way, however. It has been far too profitable to simply sell stuff dug up from under the ground—and sometimes from what’s grown on it. Manufacturing began its slow decline in the 1960s and was not helped by an enthusiastic adoption of liberalization policies in the 1980s.

Today the country has essentially no industrial policy, save for that focused on military development. Australia’s analogue of the IRA might be the nuclear submarine program of the joint Australia-UK-US pact (AUKUS), finalized in March. The goal is to boost their combined defense industrial base to deter China. Nuclear propulsion is the crown jewel of the US military industrial complex; the AUKUS agreement is only the second time it has shared the technology. The program, which includes eight Virginia-class submarines, is estimated to cost $AUD368 billion of public funds over thirty years—a substantial amount for an economy one-twentieth the size of the US.

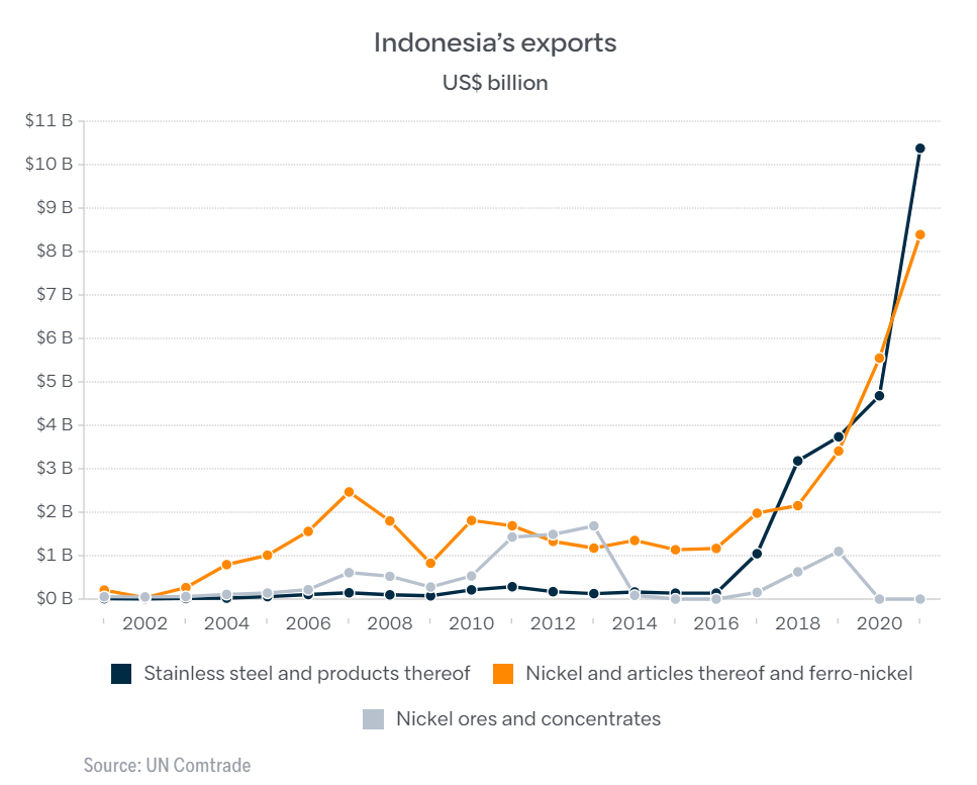

By contrast, Indonesia is strategically using its nickel reserves to move up the value chain of clean energy technologies. President Joko Widodo banned export of unprocessed nickel in 2020 and began offering incentives for production of EV batteries on domestic soil. In response, Korean companies Hyundai and LG onshored a battery facility, China’s Contemporary Amperex Technology Co., Limited (CATL) now has a processing plant, and Ford and Volkswagen also have plans. Jokowi now wants to go further and produce electric cars in Indonesia. His government is persuading Elon Musk to onshore Tesla, instead of their current $5 billion deal to import battery nickel.

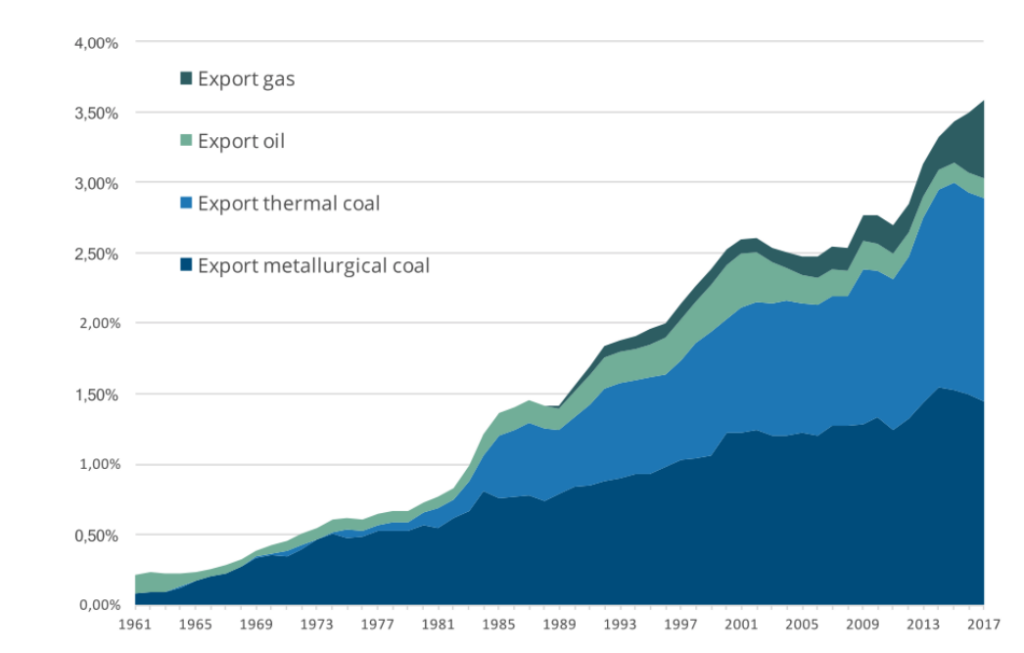

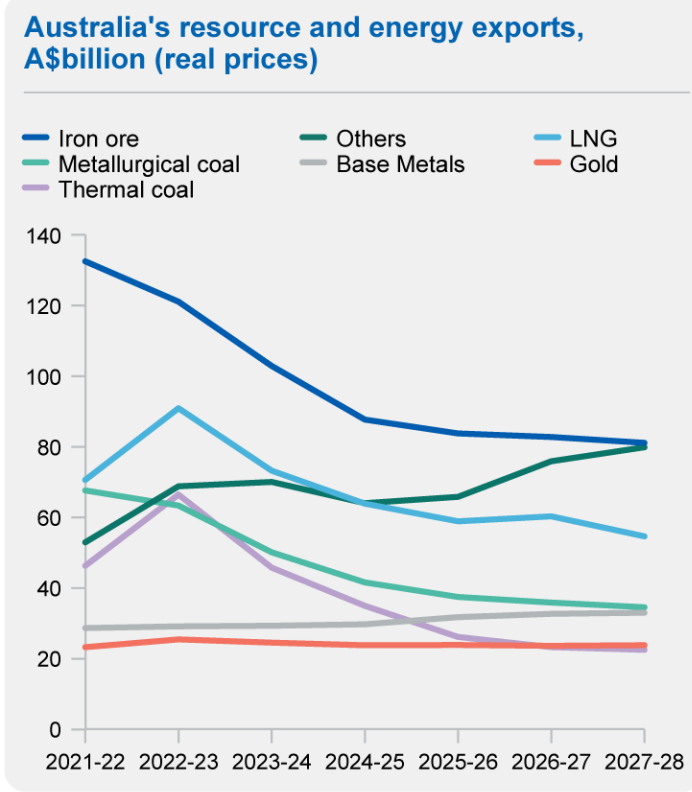

While weak on industrial policy, Australia is strong on pollution: it is one of the world’s most emissions intensive countries, on a per capita basis. Its coal and gas exports make a big contribution to this record. However, as the Grattan Institute has forecast, Australia faces the prospect of these earnings declining, because of the transition to cleaner and cheaper energy as well as China’s onshoring and near-shoring of coal from Mongolia. Australia’s liquefied natural gas (LNG) exports too are facing stiff competition from both the US and Qatar—and peak LNG demand looms.

No man is an island

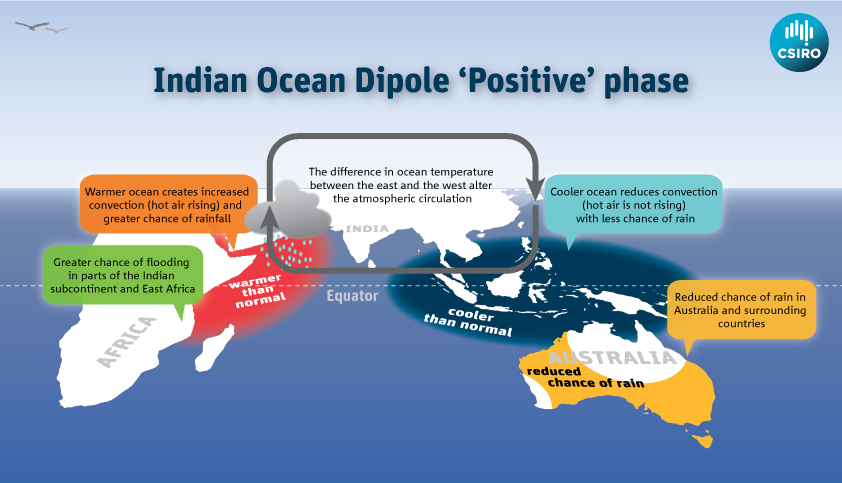

The terrible bushfires in Australia’s east during the “black summer”of 2020 were exacerbated by climate change, which amplifies the heating and drying effects of El Niño and the positive phase of the Indian Ocean Dipole. Both are predicted to return later this year, heightening the threat of bushfires in Australia and peat fires in Indonesia, as well as torrential floods in East Africa. The bushfires left millions of citizens choking, killed over a billion native animals, and prompted the Australian navy to undertake its largest ever civilian evacuation. The disaster was politically galvanizing for Australians too, who voted out the conservative government at the next election and support decarbonization. Ninety percent of Australians now want to see the climate recognized as a vital national security interest.

Australia’s single biggest export commodity is iron ore, the vast majority of which goes to China. Iron ore extraction is, in some respects, immune to the clean energy transition, as the stuff will be needed for wind turbines and buildings; the International Energy Agency projects that steel demand will grow by a third by 2050. It is not, however, immune to changes in China’s steel-intensive economic model. LNG and thermal coal export revenues are equivalent to about half of iron ore earnings.

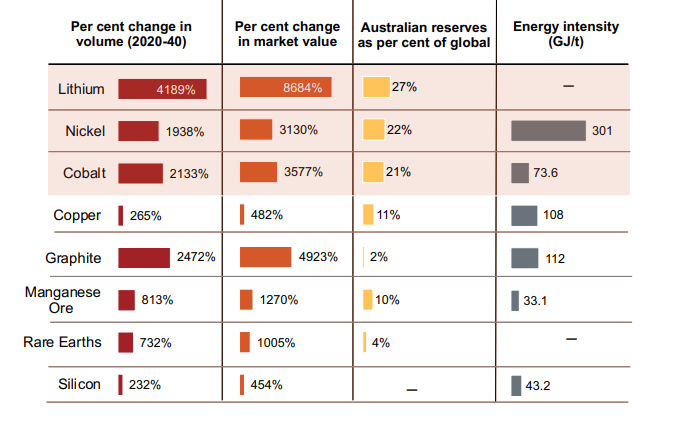

In theory, ample reserves of some transition minerals could take up a lot of slack. But will volumes and prices offset inevitable declines in other commodity exports? Long-term forecasts about the market for these substances—such as those below—very often derive from a small number of sources, and don’t explore a range of plausible demand-side measures, recycling, and material substitutions (such as sodium-ion batteries reducing demand for cobalt and lithium):

The country does not lack for capital to experiment with new industries. It has an AAA sovereign debt rating and an AUD2 trillion pension fund pool. Its more forward-looking billionaires want to export the country’s abundant sunshine and space, but distance from big markets makes that challenging. Green hydrogen, made with renewable electricity, favored by iron ore baron Andrew Forrest, is expensive to transport; the biggest users will be able to make their own closer to home. Atlassian co-founder Mike Cannon-Brookes has a big venture to send renewable electricity to Singapore, but transmitting electricity thousands of miles under the sea is, again, likely to prove too expensive.

Australia’s neighbors can perhaps see its predicament most clearly. In February, Indonesia’s chamber of commerce and industry, Kadin, signed a memorandum of understanding on critical minerals and batteries with the mining-heavy state of Western Australia. “We must use this opportunity to jointly develop a battery manufacturing factory in Indonesia taking advantage of Australia’s lithium and profitable investment to realize the potential of Indonesia’s nickel reserves and abundant workforce,” Kadin’s chairperson Arsjad Rasjid said, neatly acknowledging Australia’s comparative advantages in the twenty-first century: a large, although incomplete, complement of transition minerals and financing options that developing countries can only dream of.

Filed Under