As the pandemic forced schools shut, the Public Schools of Robeson County in North Carolina scrambled to save the rural district’s closed and crumbling buildings. At the same time, they faced the major task of providing education to children taking online classes, in a district where 43 percent of households lacked internet connection. At South Robeson Intermediate School, 20 percent of students lived in areas lacking cell service. Every two weeks that spring, parents had to pick up flash drives with lessons and instruction from the school, and return drives with completed homework; yellow school buses were repurposed into WiFi hotspots. For Robeson—as for schools across the country—the pandemic’s toll on education revealed widespread structural deficiencies.

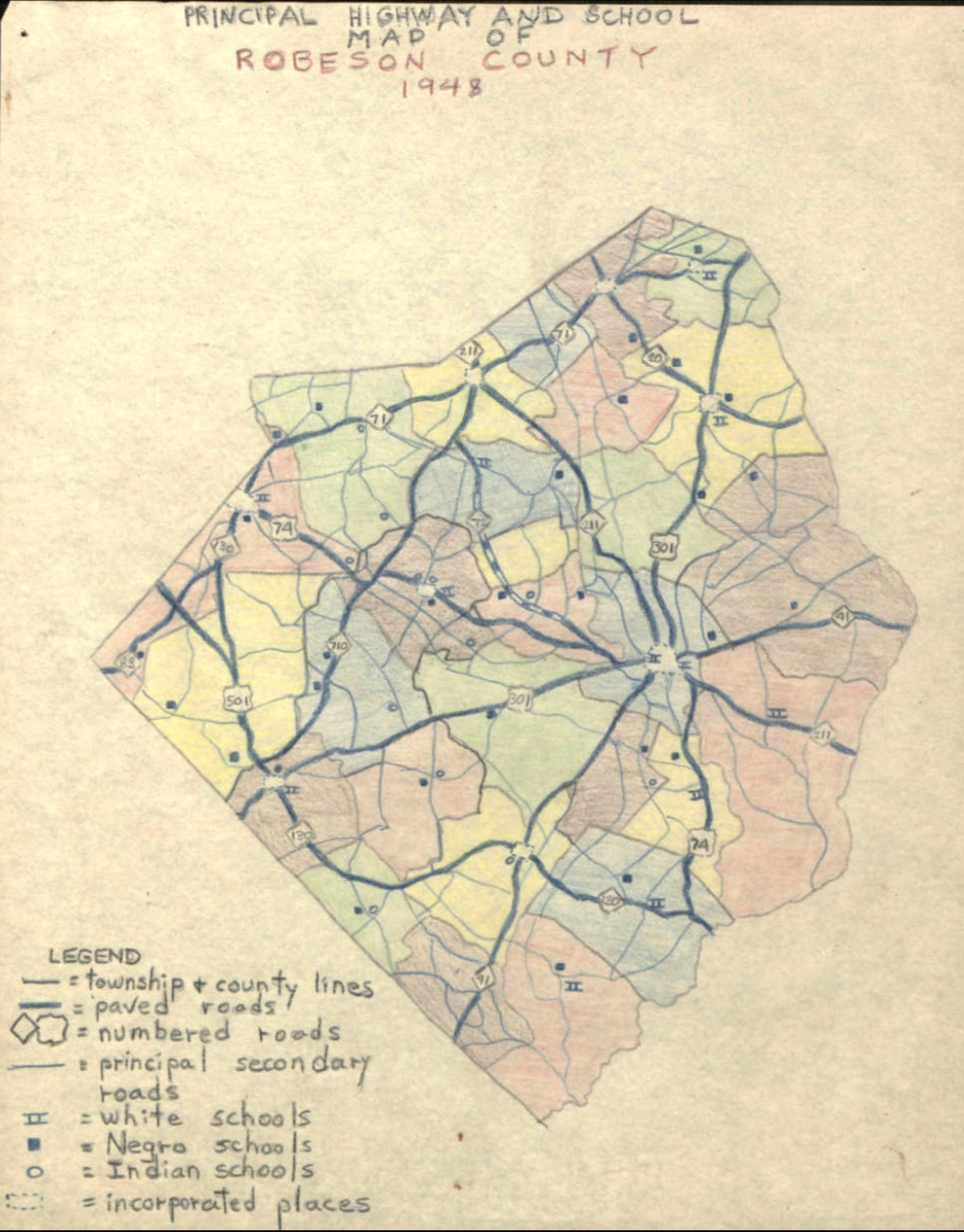

The Public Schools of Robeson County—a consolidated, countywide district—has a long history of underfunding. Previously named Robeson County Schools, the school district in the past served Black and Native American students in rural areas of the county. Separate urban districts concentrated around the county’s main towns catered to a majority white population. The school funding structure, largely based on property taxes, created ever-widening gaps between smaller, whiter districts and the larger, more diverse county school district.1 Even district mergers have not solved the longstanding legacies of Jim Crow in school funding, and inequalities have lasted to this day.2 School buildings themselves reveal decades, if not centuries, of neglect—visible in wall cracks, roof leaks, inadequate equipment, and unsafe schooling conditions.3

School finance inequality

The same trends are visible throughout the nation. Decades of data analysis have shown that money matters for education quality and equality,4 but school districts serving predominantly white students are better resourced, on average, than school districts serving students of color. Predominantly white districts receive an estimated $23 billion more in funding nationally, which corresponds to $2,200 more per student per year. While districts in communities of color often need more resources than their white counterparts, they instead face chronic underfunding.

Moreover, the gap between ultra-wealthy public school districts and the rest has grown over recent decades. The top one percent of school districts (in terms of cost-adjusted wealth) in the United States are disproportionately located in white, suburban, wealthy communities. Between 2000 and 2015, and in spite of the 2008 financial crisis, the relative wealth of these top districts increased by more than 30 percent. This reached an average of approximately $21,000 in cost-adjusted per-pupil revenues, about three times more than the average amount received by districts in the bottom 99 percent.

It’s widely known that basing school funding on property taxes contributes significantly to these large disparities between school districts.5 The funding structure is rooted in a 1973 Supreme Court decision: San Antonio v. Rodriguez closed the doors to federal reform towards school finance equity by upholding the Texas school funding formula, which partially relied on the property tax. The court argued that although the system led to gross inequities, it did not violate the US Constitution, which does not explicitly guarantee a right to education. Attorneys have litigated against the use of property tax to fund public schools at the state level since then, with mixed results.6

Disparities in school finance, however, also appear in less expected ways. They emerge through differences in state aid, teacher salaries, and other policies that on face value appear race neutral, but which intensify the accumulation of inequities over decades. The roots of these gaps are located in a patchwork of state and local discriminatory policies, some stemming from the nineteenth century and others introduced in the last few years. In my research, I look at the creation of unequal tax bases in North Carolina, through the strategic boundary drawing around tax-generating industrial property (such as Research Triangle Park), the maximization of resources for white schools, and the disproportionate investment of state and county funds towards these schools, together forming a kleptocratic political regime. Understanding these mechanisms as forms of dispossession—and recognizing their disparate origins—is crucial to countering their effects.

State policy and the persistence of funding gaps

Despite countless studies documenting district inequalities and years of school finance litigation across the nation, funding gaps have persisted. No state uses race as a factor in its school funding formula,7 and even states that have policies promoting educational equity have special exceptions, giving preference to wealthy white schools. Many of these policies were not remnants of the Jim Crow era, but rather passed and implemented in the past few decades, as a reaction to state equalization measures that sought to level district finances. The state of Kansas, for example, instituted caps on the revenue that schools can raise locally in order to promote equity between communities whose resources vary widely.8 In 2005, however, the Kansas legislature introduced a provision that raised the limit for sixteen wealthy school districts, claiming that the higher cost of living in these areas justified their need for more funding to attract teachers. This “cost-of-living” adjustment created an exception for districts that were predominantly white.

In North Carolina, where the development of charter schools has contributed to increased segregation and larger funding disparities, white communities in the suburbs of Charlotte sought to secede from the large Charlotte-Mecklenburg school district in 2017.9 Although the North Carolina legislature rejected a bill that would have created a path for any municipality to secede from county school districts, lawmakers passed two bills in 2018 that effectively circumvented this decision for those four specific municipalities through the use of charter schools.10 In these two instances, the neighborhoods that benefited from legislative exceptions have a history of racial segregation—restrictive covenants kept people of color out of white communities, and a racialized real estate market inflated property values.

Many states across the country use new legislation to build on legacies of segregation, resulting in similarly unequal school finance systems.11 Policies presented as neutral consistently benefit white districts in practice. In his study of Pennsylvania school districts, Matthew Gardner Kelly found that a provision limiting state equalization aid, which Pennsylvania lawmakers added into the state’s new school funding formula, hurt districts that served the highest number of students of color. These districts now receive less state aid, show lower levels of local and state funding for schools, and have lower expenditures than other, predominantly white districts with similar financial needs. The new legislation aimed to increase equity in school funding, but the special provision blunted its potential benefits.

Even controlling for wealth differences between school districts, funding gaps existed based on the racial composition of schools alone. Kelly identified 149 school districts that were hurt by the cap placed on state equalization aid, finding that those districts received $1.1 billion less in state equalization aid as a result of the provision. These 149 districts enrolled 79 percent of all Black and Latine students attending Pennsylvania’s public schools in 2016 to 2017. Kelly’s findings confirm earlier research about Pennsylvania, where, according to data scientist David Mosenkis, “[a]t any given poverty level, districts that have a higher proportion of white students get substantially higher funding than districts that have more minority students.”

Bruce Baker and Preston Green III found a similar phenomenon in Alabama and Kansas, two states with stark histories of racial segregation, in which laws introduced in the early 2000s entrenched disparities.12 Alabama implemented a a degree-based teacher salary system—teachers with Master’s degrees, on average, taught in schools with fewer Black students. Those schools offered higher teaching salaries, and thus received more funding. In Kansas, a policy that based organizational and cost adjustments on district size provided more funding to smaller, predominantly white rural districts. Mechanisms buried in the finer print of state funding formulas, distinct from funding allocation based on local property values, ultimately served to underfund districts serving students of color.

Contending with racist histories

In 1968, the Green v. County School Board school desegregation case pressed school districts in the nation to eliminate racial discrimination “root and branch,” but school finance inequities proved difficult to remove. The legal strategies of the mid-twentieth century focused on the psychological damage of segregation, as most notably seen in Brown v. Board of Education. To overturn the “separate but equal” doctrine of Plessy v. Ferguson, attorneys for the NAACP devised a successful legal campaign that set aside financial disparities—meaning that courts could not order equalizing remedies—in favor of ending segregation. School finance was thus separated from desegregation in the legal battle. During the last decades of the twentieth century, school finance attorneys avoided making claims of racial discrimination, knowing that it would be a losing legal strategy.

Today, funding gaps between districts exhibit more than wealth differences—schools themselves influence the value of property in a given school district. School finance policies, then, shape not only how taxes are levied, but also how school districts are formed, how their boundaries can be adapted, and how they are governed. Unequal tax bases result from deliberate policies to produce wealth differences themselves, as seen in the notorious practice of redlining.13 School districts can be seen not as fixed monoliths, but as dynamic entities whose evolution reveals loaded political choices.14

Looking closely at the boundaries of municipalities and school districts offers a better sense of these inequalities. In her historical study, Emily Straus highlights the systemic discrimination that precipitated the financial crisis faced by schools in Compton, California. Compton’s schools were excluded from neighboring districts, including Los Angeles, though Compton would have benefitted from linking its tax base to its wealthier neighbors. Instead, the district dealt with a major lack of resources due to its inadequate tax base, leaving its schools with leaking roofs and unsafe conditions. The poor state of Compton’s schools unleashed a vicious cycle by reinforcing its already low property values. It became nearly impossible for Compton to grow its tax base, and with it, its school budget.

A notable feature of school funding inequities in the United States is their ubiquity: they appear across states and regions with distinct political histories, in urban, suburban, and rural districts. My research on North Carolina shows that racial injustice in schooling persisted beyond the abolition of slavery, the legal death of Jim Crow, and the victories of the civil rights movement. Studying the formation of unequal tax bases in the state, I name the regime that has sustained and intensified these boundaries a kleptocracy.15 Many education scholars refer to these discriminatory practices as resource hoarding, but “kleptocracy” explicitly names stealing of resources from disadvantaged communities, emphasizing the relational mechanisms of dispossessions rather than wealth accumulation alone. Processes of disenfranchisement, gerrymandering, and funding allocation designed unequal wealth, the repercussions of which extended beyond how property tax funding compounded existing realities.

Halifax County, one of the case studies in my dissertation, illustrates the links between the historical roots of contemporary struggles around school finance inequalities. A rural county on the border with Virginia and among the poorest in North Carolina, Halifax County is divided into three distinct and competing school districts: Halifax County Schools, a large, rural, predominantly Black school district; Roanoke Rapids Graded School District, a small white enclave around the city of Roanoke Rapids; and Weldon City Schools, a small, predominantly Black school district. The county’s combination of Black farmer land loss, discriminatory taxation, and longstanding disenfranchisement led to the formation of these fractured and unequal districts.

County commissioners, who hold authority over local school budgets, consistently promote funding policies that favor the predominantly white Roanoke Rapids school system. Instead of basing funding on the number of students, commissioners chose to distribute the share of funds from local sales taxes ad valorem—in proportion to the property wealth of each district. Roanoke Rapids’ district budget is bolstered by the existence of three districts to segment property wealth, alongside a supplemental tax. In response, Halifax County residents have challenged the decisions of county commissioners and organized to increase Black representation on school boards.

The Halifax case shows that disenfranchisement works hand in hand with school district gerrymandering. Back in 1901, the North Carolina state legislature passed a law that regulated the implementation of a special tax that allowed school districts to supplement school budgets through a vote, while simultaneously disenfranchising Black voters in elections. As a result, white school districts across the state passed supplemental school taxes in mass numbers following the passage of the bill, which exacerbated funding disparities between Black and white schools.

Outside of state and county-level policies, funding inequalities can be traced to the school board, a hyper-local elected body. In many districts, persistent practices of disenfranchisement have diluted the influence of communities of color in school board elections.16 In 2013, voters in Wake County, North Carolina, which includes the countywide school district in and around Raleigh, formed an organization dedicated to the interests of Black residents to challenge a redistricting plan for electing the Wake County School Board.17 The plaintiffs provided evidence of racial gerrymandering for the new voting districts and contended that the school district’s redistricting plans aimed to give more weight to white suburban and rural voters, thus favoring Republican candidates to the school board. There are numerous cases of similar practices, where white communities have secured disproportionate power over educational coffers through discriminatory voting schemes.

Path forward

Scholars have analyzed three different waves in the evolution of school finance cases: equity claims based on the US Constitution, with the San Antonio v. Rodriguez case (1973), state equity cases, and state adequacy cases. Instrumental in this last shift was the emergence of standards-based reform, which introduced judicially manageable standards for educational outcomes. Adequacy-type claims revolve around the idea that students need enough resources to receive the opportunity to achieve on the state’s own standards of educational performance. While scholars today often focus on student performance, I argue that we must move beyond student outcomes. These arguments obscure inter-district differences and the process of line drawing, central to understanding school finance. An analysis of schooling must start at the root, considering how those with disproportionate power have historically manipulated taxation, school district boundaries, and voting schemes in order to exclude communities of color.

Addressing school finance inequalities and its myriad of sources presents a major policy challenge. Preston Green III and Bruce Baker have advocated for federal audits of different state school finance systems to identify policies within school systems that reinforce racial inequality and build on systemic racial discrimination. With most states reluctant to conduct these analyses themselves, they advocate for federal government intervention. Policies like canceling school district debt for the most disadvantaged communities could be a path towards more educational equity.

Until now, colorblind remedies to schooling inequality have been insufficient, but many states have implemented legislation that prevents them from using race as a criterion to distribute educational resources. Court decisions that have mandated school finance reform have indirectly led to moderate results on lessening inequality, but the racial gap persists. Many of these legal remedies have ordered states to guarantee the provision of an adequate education, meaning a minimum threshold of instruction, without addressing inequities between the wealthiest and poorest districts. The persistent failure of these reforms thus far calls for a radical reframing of the issue. Naming resource inequalities as actual theft, rather than static differences, could be a start.

FootnotesEsther Cyna, “Shortchanged: Racism, School Finance and Educational Inequality in North Carolina, 1964-1997,” Ph. D. dissertation, Teachers College, Columbia University (2021), Chapter 2.

Esther Cyna, “Equalizing Resources v. Maintaining Political Power: Paradoxes of Suburban-Urban School District Merger in Durham, North Carolina, 1958-1996,” History of Education Quarterly, vol. 59, iss. 1 (February 2019): 35-64.

Esther Cyna, “Funding the High School of Tomorrow: Inequity in Facility Construction and Renovation in Rural North Carolina (1964-1997),” in Kyle Steele (dir.), New Perspectives on the History of the Twentieth-Century American High School (Palgrave Macmillan Press, 2021).

National studies of school finance reform have shown that increases in education spending can lead to improved outcomes such as increased standardized test scores, higher graduation rates, and adult earnings. Lafortune, Julien, Jesse Rothstein, and Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach, “School Finance Reform and the Distribution of Student Achievement,” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, vol. 10, iss. 2 (2018): 1-26; Christopher A. Candelaria, Kenneth A. Shores, “Court-ordered Finance Reforms in the Adequacy ERA: Heterogeneous Causal Effects and Sensitivity,” Education Finance and Policy, vol. 14, iss. 1 (2019): 31-60; C. Kirabo Jackson, Rucker C. Johnson, Claudia Persico, “The Effects of School Spending on Educational and Economic Outcomes: Evidence from School Finance Reforms,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, vol. 131, iss. 1 (2016): 157–218.

Charles J. Ogletree, Jr. and Kimberly Jenkins Robinson (eds.), The Enduring Legacy of Rodriguez: Creating New Pathways to Equal Educational Opportunity (Harvard Education Press, 2015); Bruce Baker, Educational Inequality and School Finance: Why Money Matters for America’s Students (Harvard Education Press, 2018); James E. Ryan, Five Miles Away, A World Apart: One City, Two Schools, and the Story of Educational Opportunity in Modern America (Oxford University Press, 2010).

San Antonio Independent School District v. Rodriguez, 411 U.S. 1 (1973).

The Sheff v. O’Neill school finance case in Connecticut, filed in 1989 and first decided by the Connecticut Supreme Court in 1996, illustrates the difficulty of framing school finance as a racial discrimination issue. Plaintiffs in Sheff challenged district fragmentation, suburban poverty, and racial isolation in Hartford, Connecticut, and argued that racial isolation was the connection between school finance and desegregation. The case did not cast segregation as inherently harmful because of social homogeneity, but instead showed that the boundaries that upheld segregation deepened inequalities. The plaintiffs argued that racial integration and funding equity in tandem would transcend these boundaries in order to try and undermine their oppressive effects. The case, however, yielded mixed results. Its remedy failed to redraw district lines, and instead led to the creation of magnet schools to encourage integration. For more, see Susan Eaton, The Children in Room E4: American Education on Trial (Chapel Hill: Algonquin Books, 2007); Jack Dougherty, “Sheff v. O’Neill: Weak Desegregation Remedies and Strong Disincentives in Connecticut, 1996-2008,” in Claire Smrekar and Ellen B. Goldring, (eds.), From the Courtroom to the Classroom: The Shifting Landscape of School Desegregation (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2009), 103-12.

Daniel R. Mullins and Bruce A. Wallin, “Tax and Expenditure Limitations: Introduction and Overview,” Public Budgeting & Finance, vol. 24, issue 4 (2004): 2-15; Preston Green III and Bruce Baker, “How Reparations Can Be Paid Through School Finance Reform,” The Conversation, September 16, 2021.

The four wealthy suburban White communities were Cornelius, Huntersville, Matthews and Mint Hill. See Helen Ladd, Charles Clotfelter and John Holbein, “The Growing Segmentation of the Charter School Sector in North Carolina,” Education Finance and Policy, vol. 12, no. 4 (2017): 536-563; and Jenn Ayscue, Amy Hawn Nelson, Roslyn Arlin Mickelson, Jason Giersch, and Martha Cecilia Bottia, “Charters as a Driver of Resegregation,” Civil Rights Project, January 2018.

North Carolina General Assembly, Session 2017 Session Law 2018-3 House Bill 514; North Carolina General Assembly, Session 2017 Session Law 2018-5 Senate Bill 99.

Bruce Baker and Sean Corcoran, The Stealth Inequities of School Funding: How State and Local School Finance Systems Perpetuate Inequitable Student Spending, Center for American Progress, 2012; Leanna Stiefel, Amy Ellen Schwartz, Robert Berne, Colin C. Chellman, “Finance Court Cases and Disparate Racial Impact,” Education and Urban Society, vol. 37, iss. 2 (2005): 151–173.

Bruce Baker and Preston Green III, “Tricks of the Trade: State Legislative Actions in School Finance Policy that Perpetuate Racial Disparities in the Post-Brown Era,” American Journal of Education, vol. 111, iss. 3 (2005): 372–413.

Literature on racial capitalism has been extremely fruitful in exposing historical racist public policies. See Destin Jenkins, The Bonds of Inequality: Debt and the Making of the American City (University of Chicago Press, 2021); Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, Race for Profit: How Banks and the Real Estate Industry Undermined Black Homeownership (University of North Carolina Press, 2019).

Education historians have traced the history of specific school districts to highlight the political weight of policies affecting their boundaries. On the history of the American school district, see David Gamson and Emily Hodge (eds.), The Shifting Landscape of the American School District: Race, Class, Geography, and the Perpetual Reform of Local Control, 1935-2015 (New York: Peter Lang, 2018).

I define “kleptocracy” as a system rooted in law and policy that relies on the theft of rights, land, capital and labor from people of color to engineer unequal wealth between white people and people of color. Ta-Nehisi Coates and Van R. Newkirk II have used the term “kleptocracy” to talk about systemic racial oppression. Ta-Nehisi Coates, “The Case for Reparations,” The Atlantic, June 2014; and Vann R. Newkirk II, “This Land Was Our Land” / “The Great Land Robbery,” The Atlantic, September 2019. The word “kleptocracy” otherwise appears in literature about foreign dictatorships, especially in Eastern Europe and Russia, where it refers to government confiscation. In the U.S., scholars have used it in the context of governmental property seizure related to criminal activity. Leonard Levy, A License to Steal: The Forfeiture of Property (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996).

Historian Robert Margo studied the relationship between Black disenfranchisement and school finance at the turn of the twentieth century in Louisiana and Alabama. Robert Margo, Disenfranchisement, School Finance, and the Economics of Segregated Schools in the United States South, 1890-1910 (New York: Garland, 1985).

Raleigh Wake Citizens Ass’n v. Wake Cnty. Bd. of Elections, 166 F. Supp. 3d 553 (E.D.N.C. 2016)

Filed Under