We live in a period of unparalleled financial complexity, and, as the history of recent decades has demonstrated, unparalleled financial risk. The recurring crises which plague the global economy have brought theorists of systemic instability to the fore. Key among them has been Hyman Minsky, whose framework for understanding financial market fragility takes a cyclical form. In his model, an excessive credit expansion (“displacement”) fuels a speculative bubble (“mania”) and causes “financial distress,” leading to credit contraction and the bursting of the bubble (“panic”).

The appeal of Minsky’s model lies, in part, in its structural perspective. In contrast to the general tendency to disregard financial market practices, Minsky leveraged institutional and legal structures of the financial markets to develop his views. A classic example is his interpretation of the 1980s debt crisis—unlike orthodox theories of profit determination based on productivity and market power, Minsky linked firms’ performance to the developments of the financial market. Specifically, he focused on the 1980s merger and acquisition mania and the structure of junk bonds. Whereas neoclassical theories priced cash flows based on profitability, Minsky analyzed them as claims on firms’ tangible assets, which were often used as collateral for junk bond loans. In the 1980s, financial distress thus enabled issuers to refrain from making payments, generating a liquidity crisis that neoclassical frameworks could not understand.

In Minsky’s vision, instability is an essential characteristic of market structure. Because credit expansion depends on the creation of private monetary instruments, and a panic involves a flight from such speculative assets towards safe, liquid monetary liabilities issued by a central bank, his framework opens the way for analyzing how the hierarchy of monetary liabilities influences the stability of the system as a whole.

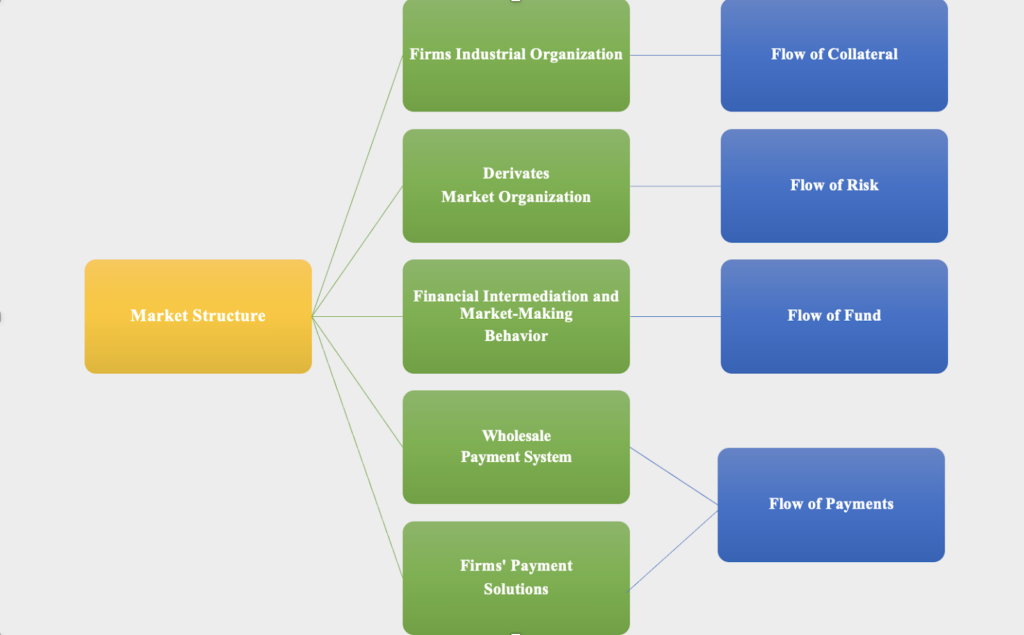

By demonstrating how instability is generated, Minsky’s theory is a valuable guide to policymaking aimed at controlling systemic risk. However, most of the work inspired by Minsky uses it to understand instability after the fact. In examining the ex-ante formation of systemic risk, economists narrowly focus on the status of short-term funding and monitor a few liquidity or volatility indicators. Consequently, the structural and institutional aspects of derivative markets, payment systems, and the supply chain of collateral, remain a black box. I take the black box as my primary point of departure—examining the intricate workings of financial stability through market microstructures underlying financial flows.

The most established financial flow indicator is the flow of funds. Inspired by Walter Bagehot’s monetary world and Minsky’s market structure vision, macroeconomists began to examine sources and uses of short-term funding. Traditionally, the flow of funds was sufficient to capture the market structure’s resilience and financial stability. This is because the financial participants’ search for liquidity represented the real economy’s aggregate demand. However, the flow of funds alone cannot sufficiently reflect the institutional realities of the modern financial ecosystem.

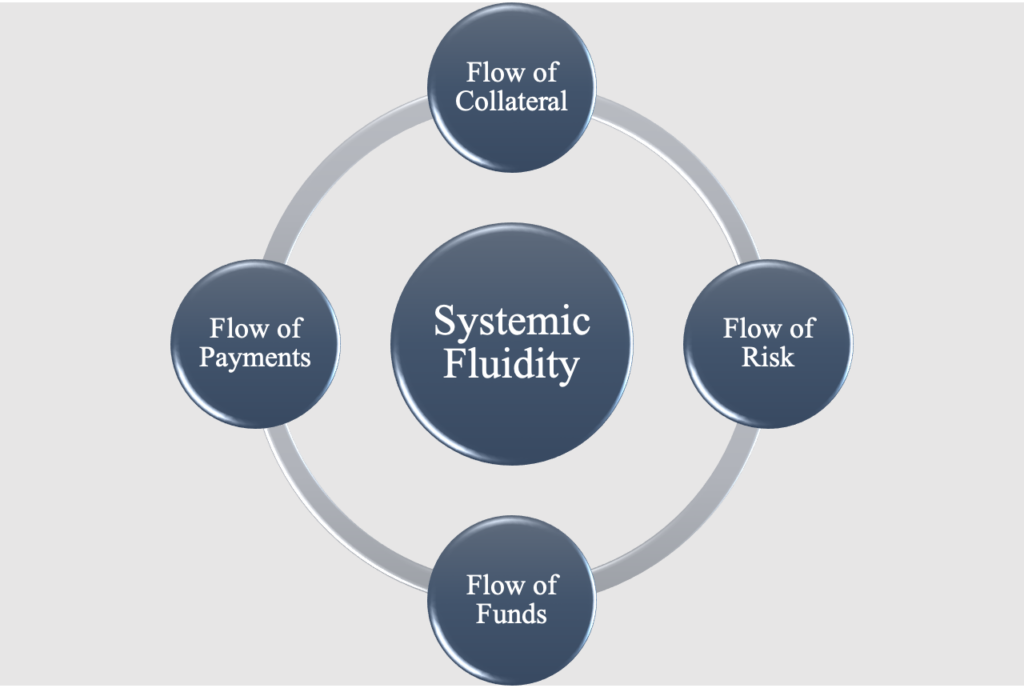

For example, in a shadow banking system, the demands for short-term funding are not driven by transaction needs in the real economy. Instead, they reflect the state of the collateral supply chain, institutional aspects of the derivatives market, and the structure of payment systems. Therefore, to analyze financial stability, we should update the measure of financial flow and supplement the flow of funds with three new sets of flows: the flow of collateral, the flow of risk, and the flow of payments.

Together, these flows give insight into the microstructure of financial markets—the mechanisms which drive the willingness of financial participants to trade. The transactions resulting from this willingness contribute towards overall systemic fluidity.

Crucially, this approach doesn’t take liquidity for granted. Instead, liquidity exists when the mechanisms underpinning transactions work seamlessly. While liquidity is necessary for systemic fluidity, it is not the only determinant. In the framework I present below, each element of systemic fluidity is linked to a particular market microstructure: collaterals move between different types of entities in accordance with firms’ industrial organization. The flow of risk depends on the institutional qualities of derivative markets, which, through derivative dealers, can distribute risk across the financial system. The flow of funds depends on the quality of liquidity in circulation, which in turn is shaped by the structure of the market for financial intermediation. Finally, the flow of payments depends on the tendency of two systemically important aspects of the payment infrastructure, the two-stage payment mechanism and firms’ payment solutions, that accumulate junk liquidity and siphon off high-quality claims.

Analyzing changes in market microstructure thus presents a constructive avenue through which to understand and predict the fluidity and stability of financial markets. By analyzing research outputs from key financial actors and reflecting on them with researchers from these institutions, this essay and accompanying posts aim to let the market speak in real time. It will leverage academic frameworks to cut through the many noises of market-generated narratives, differentiating structural, cyclical, and event-driven market shifts. In this first piece, I take a focused look at the relationship between financial flows and market microstructures in order to set the groundwork for analysis in subsequent articles.

The flow of collateral

Transactions on wholesale capital markets are often secured by marketable collateral. Collaterals flow for different purposes, including secured funding, investment, short-selling, margin requirements, and lending by securities owners. The flow of these securities is a cornerstone of system-wide fluidity—if collaterals are not delivered on time or arranged cheaply, funding will evaporate.

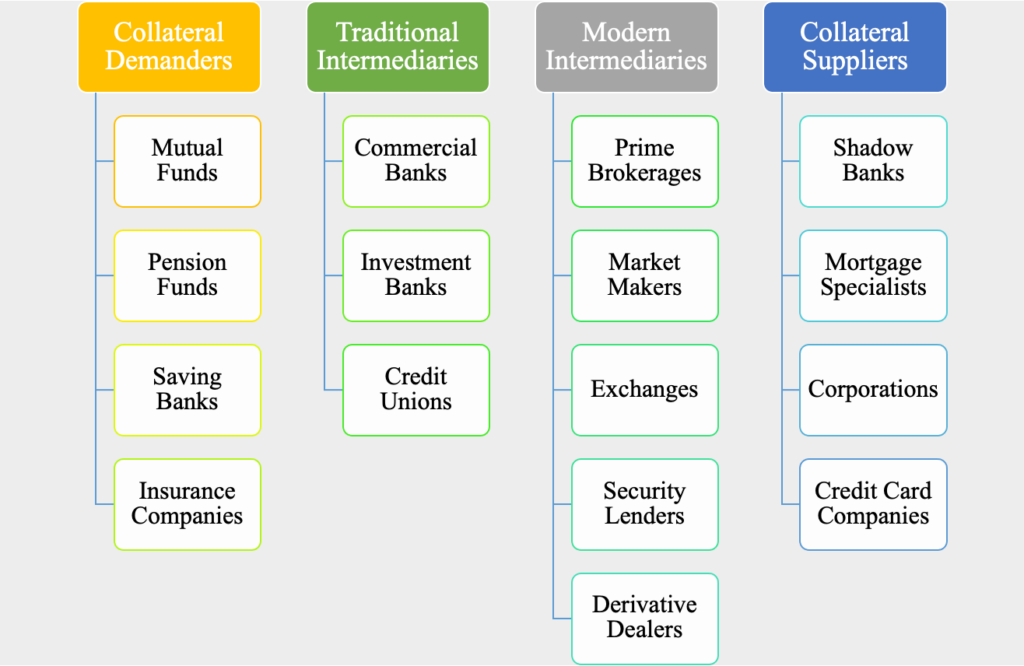

Classical financial stability models tend to focus on the role of financial intermediaries like broker-dealers in managing the securities market. But in reality, collaterals flow through a wide range of institutions with varying business models— including institutional investors, money market funds, asset managers, and securities firms. The economic structures and balance sheets of each of these institutions underpin the collateral supply chain.

The collateral chain is essential for the functioning of the modern financial system, but it remains grossly understudied. Understanding the collateral supply chain requires outlining the particularities of each actor’s industrial organization, including its degree of market power, balance sheet positions, and interactions with market structure.

There has been a recent and burgeoning theoretical literature which argues that firms’ market power determines their willingness-to-pay for securities. This willingness-to-pay, in return, affects the resale value of securities used as collateral in the money market. In addition, it can change the market structure by influencing regulators’ behavior and other market practices. Our interest is in understanding the type of firm-level industrial organization strategies that affect the stability of overall market structures.

Financial firms may adjust their business strategies, as they do with Collateral Management and Assets and Liabilities Management (ALM), and actively shape collateral flows. Through collateral management processes, firms strategically match assets and liabilities or adjust the type of collaterals they accept from counterparties like banks, broker-dealers, insurance companies, hedge funds, and pension funds. These strategies can help maximize utility, achieve higher investment returns, and reduce counterparty risks at the firm level. At the market level, however, the adjustments can alter securities lending and investment activities by shaping the type of securities companies are willing to acquire and their willingness-to-pay.

In this way, firms’ business management practices can affect an entire industry. Indeed, the increase in securities lending post-2000, the secular decline in market-making post-2008 Great Financial Crisis, and the sell-off of the US Treasury securities in March 2020 are examples of the systemic impacts of such firm-level strategies. In viewing firm balance sheets as a pipeline of collateral flows, we can uncover hidden vulnerabilities underlying market operations. We can also understand how shocks are transmitted and amplified between different firms. Thus, combining the overlooked industrial organization of the non-intermediaries with that of the more well-known financial intermediaries helps pave the way to a new framework describing the financial system.

The flow of risk

Derivative markets are the key structure underlying risk distribution within the financial system, separating the flow of risks from the flow of collaterals. If firms were to lend their securities without proper hedging strategies, they would assume an unsecured and undiversified counterparty credit risk which may not obtain the risk manager’s approval. Institutional investors’ function as securities lenders partially stems from the existence of derivatives that transfer the risks to willing counterparties.

In turn, the availability of derivatives and hedging strategies depends on institutional aspects of the derivatives market, such as the market-making mechanisms, their legal structure, and financial engineering.

While derivative strategies are considered essential for firm-level risk management, they are often described as “financial weapons of mass destruction” and condemned as a “trigger” of the 2008-09 financial crisis. Derivatives are absent from balance sheets—having no initial value, they are not bought or sold, and consequently remain unrecorded by position takers.

But their absence from balance sheets is not the only attribute shaping derivatives’ net impact on systemic fluidity. Derivatives separate the flow of risks (foreign exchange, interest rate, and credit) from the flow of collateral. Thus, they strip risk from financial assets and become the parallel track required for shifting hedged collaterals across the financial industry. In this way, they transform collaterals into funding and enable market makers to provide liquidity. Derivative markets thus provide a market-based structure for risk management and collateral valuation.

Derivative positions also determine the fluidity of collaterals by reducing counterparty credit concerns and protecting against exposures. Financial instruments like US Treasury bonds can be traded as at least two separate instruments: they can be used as collateral to obtain short-term funding and make payments, or used as derivatives like interest rate swaps (IRS) and credit default swaps (CDS). The first shifts interest rate risks, and the second distributes the default risk from the issuer to the derivative holder.

In addition to enabling the flow of collateral and secure funding, derivatives also allow for the ongoing swap of IOUs in the form of cash. This parallel loan construction creates a web of hidden short-term debts which can pressure the traditional bank-based payment system both within and across borders.

For instance, interest rate swaps typically involve temporarily exchanging floating interest payments for fixed ones. Similarly, credit-default swaps require the derivatives issuer to make periodic payments to its counterparty as a kind of insurance premium. These payments parallel the debt issuers’ periodic interest payments, so that the time pattern of the derivatives holders’ payments mirror that of the issuers of debt securities.

The parallel loan structure of derivatives links them to system-wide liquidity and funding conditions. A mark-to-market financial engineering technique, in which investors pay for daily gains or losses according to changing asset value, makes derivatives’ actual cash flow commitments higher than their implied level. In doing so, it converts otherwise cash-rich institutions, such as pension funds, into vehicles of systemic liquidity risk.

Cash-pool investment vehicles like pension funds use derivative strategies to hedge significant pension plan liabilities against interest rate risks. Because they hold large cash pools, they simultaneously use derivative techniques such as Liability-Driven Investment (LDI) to earn higher yields. These institutional investors’ dual role in the derivative market exposes them to significant margin calls during large price swings. In this way, the cash-rich investors transform into vehicles of systemic liquidity vulnerabilities.

Finally, derivatives directly link financialized commodity markets with the broader financial system. Because derivative contracts in large part depend on commodities, fluctuation in their prices can generate excessive margin calls. Through a financialized business model, derivatives allow commodity traders to exploit their information advantage as the market makers. As non-financial corporations, however, they ultimately rely on bank funding. The mark-to-market nature of derivatives means that large swings in commodity prices can expose them to significant and frequent margin calls. In this way, commodity traders’ extensive usage of derivative strategies and over-reliance on bank funding can cause system-wide liquidity vulnerabilities.

Derivatives are thought to be toxic for overall financial stability, especially after 2008. However, derivatives mediate broader stability in far more nuanced ways. Their concealment of actual leverage in circulation, off-balance sheet calculation, and unpredictable margin calls can make these instruments dangerous. However, derivatives are also the backbone of secured funding. These instruments strip risks of long-term securities, convert them into collateral, and become the source of immediate liquidity. Furthermore, derivatives can be valuable for managing business risks and expanding operations with relative safety.

An institutional approach toward the derivatives market provides a robust framework for examining the risks and benefits of these instruments for financial stability. The goal is to design a type of derivatives market that becomes vital plumbing for the simultaneous flows of collateral and risk in the system. This aspect, which is relegated to the background in most financial stability frameworks, will be a critical parameter of our approach when assessing the systemic impacts of derivatives.

A narrative of the crisis that overstates the threat of derivatives can lead to policies that excessively limit and depress their use. The outcome will not be a more resilient financial system but one in which various business risks that have been hedged with derivatives will sprout up in their absence.

The flow of funds

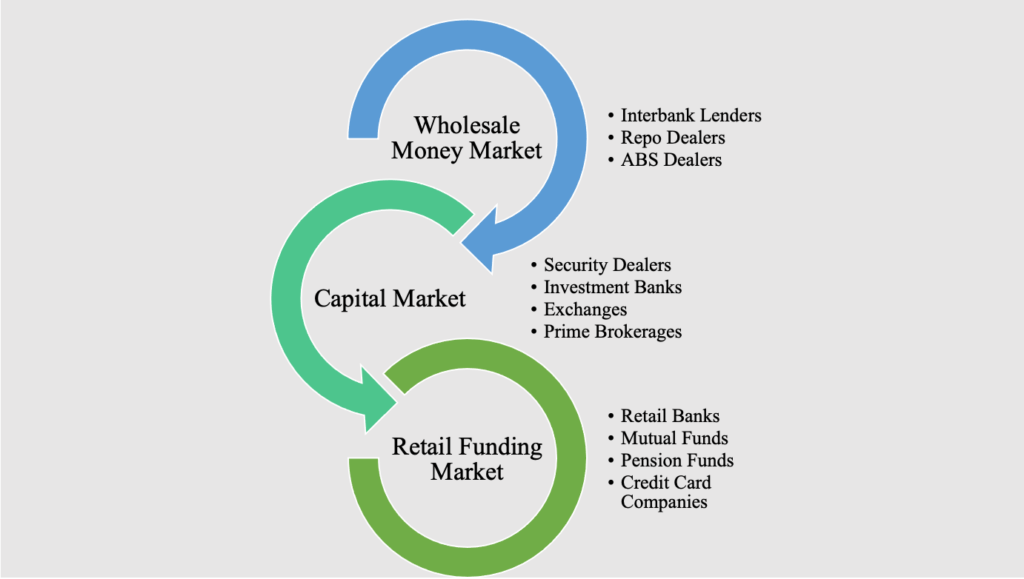

Unlike collateral flows, which are delivered in the long-term capital market, funding is provided in the short-term money market. The seamlessness with which funding flows across the financial system depends in large part on the quality of monetary liabilities in circulation. The changing composition of players and activities all shape this quality.

In the financial ecosystem, short-term monetary liabilities are produced, traded, and priced in the market for financial intermediation. The microstructure of this funding market is determined by how traders on the sell- and buy-side share their responsibilities and roles. Liquidity providers (banks, dealers and brokers) and liquidity takers (asset managers) form the pipeline that moves funds across the system. Thus, the resilience of this pipeline depends on the dynamics in each of these spheres.

This financial intermediation process is performed by various players operating at different levels of the supply chain of funds. Nonetheless, regarding the degree of “cash equivalence,” not all players on the sell-side of funding instruments provide the same quality. The hierarchy of liquidity providers, ranked by their business model and the type of intermediation, is an essential characteristic of the financial intermediation industry. For instance, a traditional financial intermediary simply connects cash-rich to cash-deficit agents without making the market for funding. Similarly, the modern brokerage business only connects different counterparties and provides information about fair prices through financial analysis. These sell-side entities provide conditional liquidity by connecting traders with opposing needs.

By contrast, market makers, including dealers, are the source of continuous liquidity. This is because they are unbiased liquidity providers who trade with any interested trader. When a dealer absorbs monetary instruments onto its own balance sheets, it creates a position in those instruments. In doing so, it establishes long positions in certain assets and short ones in others—if a repo dealer borrows cash from an overnight market and lends it to the term (i.e., three-month) market, it has a long position in term repo loans and a short position in overnight cash loans.

This inventory position generates risks by preserving long term monetary liabilities. Dealers can shed this risk by trading out the claims if circumstances allow. By using their balance sheets to absorb unwanted inventories in order to acquire rewards, dealers make markets. Because they provide continuous liquidity, prices, and liquidity risk premia, they are at the top of the sell-side hierarchy.

The buy-side’s access to funding is equally hierarchical. Monetary liabilities in circulation have varying levels of quality, and high quality funding is unequally distributed. Financial firms at the top of the hierarchy have access to highly convertible and liquid monetary instruments, including central bank reserves. Others, however, have to pick from a menu of shadow funds, which are expensive and provided by low-rated and unstable liquidity providers.

In normal times, the elasticity of credit and frequency with which shadow funds are traded blurs the buy-side hierarchy. But during a crisis, the double hierarchies of the sell-side and buy-side bind simultaneously and to the fullest extent. Not only does the distinction between the sell-side and buy-side become unmistakable, but the different qualities of liquidities in circulation also become evident. When this happens, the pipeline and infrastructure that circulates funding, in dynamics between the sell-side and buy-side, become the vessel for moving liquidity risk across the system.

The linkage between the sell-side and buy-side, rather than the resilience of a few systemically important financial institutions, can aggravate an idiosyncratic funding problem into a system-wide liquidity crisis. Understanding the linkages between funding, collateral, and derivatives of the financial web is necessary for exploring the financial system as a dynamic process rather than a snapshot. Rather than focusing on cash and balance sheet items, our systemic fluidity framework shows these complex movements and shifts.

The flow of payment

The payment system is the real life stress test of the system-wide tendency to hoard junk liquidity and siphon off high-quality claims. The financial system continually transforms public claims into private claims through two different channels: the payment processing system and firms’ liquidity and payment solutions.

The former is composed of payment and settlement, where the quality of claims in the first stage is usually lower than that in the final stage. The latter continually transforms the liquidity and maturity of firm balance sheets. Both tend to hoard bogus liquidity and siphon off public liquidity, but the system’s overall quality depends on the trust that relatively safe and secured monetary liabilities exist at every layer. These claims are made by collateral-taking private entities or the government’s presence as a lender of last resort.

The liquidity transformation that occurs in the system has two separate roots. The first component is the intrinsic feature of the payment system. Every payment starts and ends with liquidity. However, the quality of funding instruments required to settle each stage differs. Payments are processed in two phases. The first stage, known as the payment stage, is when the promise to make the final payment is made. These promises to pay are usually funded by exchanging collateral (secured funding) or short-term monetary liabilities (unsecured financing). At this stage, at each layer of the hierarchy, payments happen as a conversion of the lower-quality liabilities into higher-quality ones (issued by entities at the higher layer of the sell-side hierarchy). In the first stage, the hierarchical structure of funding instruments remains invisible.

However, this hierarchy becomes binding in the final stage of payment. At this stage, all the net payments should be settled and cleared. The final clearance happens only if the payment system can convert the remaining payments into the highest-quality form of money, such as the central bank’s reserve or cash. A systemic problem will happen if this convertibility is not economical. In this case, the conversion, if it happens, will be at a penalty or negotiable at prices lower than par and cause system-wide missed payments. The continuity of liquidity transformation in the first and last stages of payments determines the resilience of payment flows. The payment flows seamlessly only if there is a systemic trust that relatively safe and secured monetary liabilities exist at every layer.

The second channel reflects the corporates’ cash management strategies. Various types of financial and non-financial participants are involved in the payments ecosystem. Importantly, all these large firms use somewhat similar liquidity and payment solutions to meet their daily cash flow constraints. For instance, the two core and standard liquidity management techniques are netting and cash pooling. Netting aims to reduce funds transfer between subsidiaries or separate companies by settling the funds to a net amount. Cash pooling allows enterprises to combine positive and negative positions from various bank accounts into one account. This aims to reduce short-term borrowing costs and maximize returns on short-term cash. Corporate treasurers’ payment solutions, an often overlooked aspect of systemic risk, link the business models of otherwise wildly divergent firms with each other. As a result, the liquidity transformation that happens at the firm level can leave industry-level footprints on the payments system.

Corporate treasurers manage liquidity and payment costs by not leaving liquid assets uninvested for at least two reasons. First, the monetary instruments earn very low-interest rates. Second, the wholesale cash is uninsured and exposes the corporates to credit risk. If and when funding is required to ensure the payment accounts remain in a positive balance position, they convert these investments back to more cash-like instruments. As a result, they change the level of liquidity transformation daily and expose the system to systemic forecasting errors.

Through channels such as “payment system” and “firms’ liquidity and payment solutions,” the financial ecosystem transforms public (high-quality) claims into private (lower-quality) ones. Many transformations are taking place in the complex payment system infrastructure. The two-stage payment mechanism is based on an inherent mismatch between the quality of the claims at the different layers. The type of acceptable claim in the first stage, dubbed the “payment” stage, is usually of a lower quality than in the second stage, called the “settlement” stage. In addition to the black box of the payment system, and at a firm level, treasurers’ liquidity and payment solutions enhance the liquidity mismatch between their balance sheets’ asset and liability sides. From a holistic perspective, the payment system is built on a tendency to hoard bogus liquidity and siphon off public liquidity. In this environment, the market structure’s quality depends on the “trust” that relatively safe and liquid claims exist at every stage. Such trust ultimately depends on the willingness of collateral-taking private entities or the central banks to extend high-quality liquidity.

In standard times, these strategies might not be consequential. Large corporates have access to short-term money market funding. In this system, money market dealers act as the ultimate corporate treasurers and correct their cash flow miscalculations. In doing so, money market dealers become the linkage between payment flows and short-term funding. In crisis times, however, this link might break. Under such circumstances, market makers usually exit the market. In this case, the full force of the liquidity mismatch embedded in the financial ecosystem becomes visible to everyone. Corporate treasuries’ liquidity and payment strategies can expand the current level of liquidity transformation in the ecosystem and make its management unsustainable. In such circumstances, the payment system that inherently depends on the system-wide ability to manage such transformation will break down.

Conclusion

Although invisible, market microstructure is the infrastructure underlying the financial system. In particular, its destabilizing dynamics can vividly disrupt the financial system’s fluidity captured by the shifting nature of collateral, the distribution of risk, the transmission of funding, and flow of payments. Although these four pillars of systemic fluidity can be examined individually, they are inseparable features of real world market structure. Forthcoming posts will delve into the industrial organization of firms, the dealing mechanisms and engineering of derivatives, the hierarchies of financial intermediation, and the structure of the payments system. Instead of monitoring liquidity and volatility indicators, we look inside the black box of the market structure, where the pressing concerns of market participants and regulators are found.

Filed Under