This is the second edition of The Polycrisis newsletter, written by Kate Mackenzie and Tim Sahay. Subscribe here to get it in your inbox.

The economic fallout of the pandemic hit Latin America harder than almost anywhere else in the world, kicking 12 million people out of the middle class in a single year. In a string of recent elections—Chile, Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador—voters have punished incumbent politicians, and the winner has been Latin America’s left. The question facing the continent is whether the new Pink Tide can become a green one.

In his victory speech on Sunday, flanked by trade unionists and landless peasants, Brazilian President-elect Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva pledged to pursue strategic non-alignment. “We will not accept a new Cold War between the United States and China. We will have relations with everyone.” China is already Brazil’s largest trading partner and Brazil chose not to join the G7 sanctions on Russia, citing its agricultural sector’s dependence on Russian fertilizers. South-South cooperation may be a big theme of his presidency; Lula’s speech mentioned South American and Caribbean alliances, BRICS, and collaboration with African countries.

We will resume the monitoring and surveillance of the Amazon, and combat any and all illegal activities, whether they be mining, logging, or improper cattle ranching. – Lula, victory speech.

When Lula was last in power, soy and beef moratoriums reduced Brazil’s deforestation of the Amazon by 80% between 2004 and 2012, even as Brazilian agricultural production boomed. Norway paid over a billion dollars to Brazil for avoided deforestation. Brazilian law enforcement agencies used Indian and Chinese satellites to monitor deforestation from space, while police and prosecutors enforced it on the ground.

Bolsonaro’s parliamentary coalition of rural agribusiness interests—the so-called beef, bible, and bullets coalition—blew up that deal. Without Lula-era enforcement of environmental laws, criminal gangs and agribusiness companies pushed the soy and beef frontier further into the Amazon rainforest, driving a massive spike in deforestation. The most egregious culprit was the meatpacking company JBS, which runs the world’s largest slaughterhouses and processes a quarter of the planet’s beef, and whose emissions from deforestation are larger than all of Italy’s.

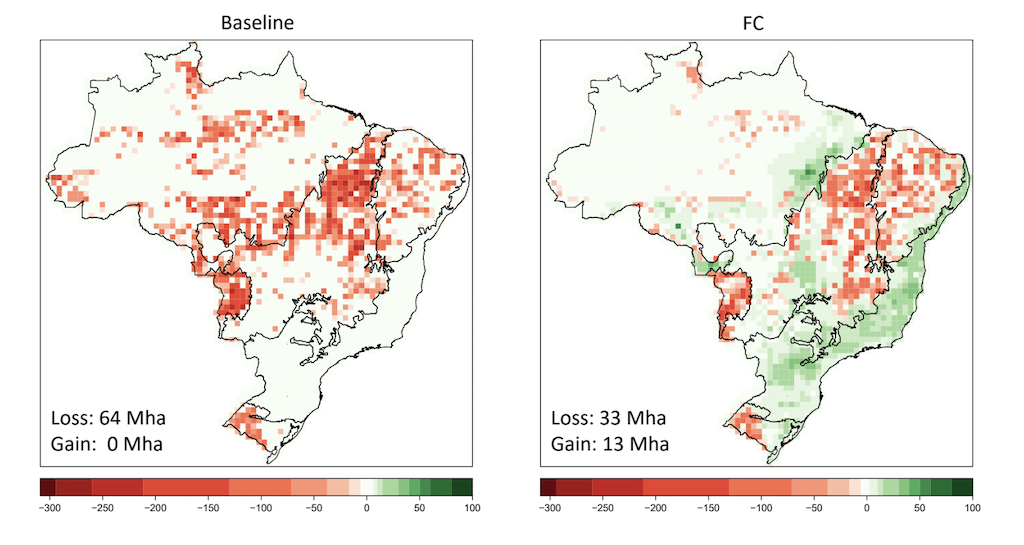

A Lula government that enforces the decades-old Forest Code could see Amazon deforestation dramatically reduced, and some restoration in parts of the south and south-east.

Regions that are worse off in the right-hand map above include the Cerrado grasslands in eastern Brazil, which are less carbon-rich than the Amazon but nevertheless serve as major stores of carbon dioxide. Lula and Dilma Rousseff’s earlier governments also protected the country’s northern Amazon regions, turning a blind eye to forest clearing in other regions.

Just as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine spurred more fossil fuel extraction, the Trump administration’s tariff war against China accelerated the pace of clearing land for soybean crops in Brazil, as China stopped buying US soy. Soybeans are Brazil’s biggest export earner. Beef, meanwhile, drives most Brazilian land clearing, and here, pressure from outside Brazil matters less than national politics, since 80% of the beef produced is consumed domestically.

Who will be Lula’s Manchin?

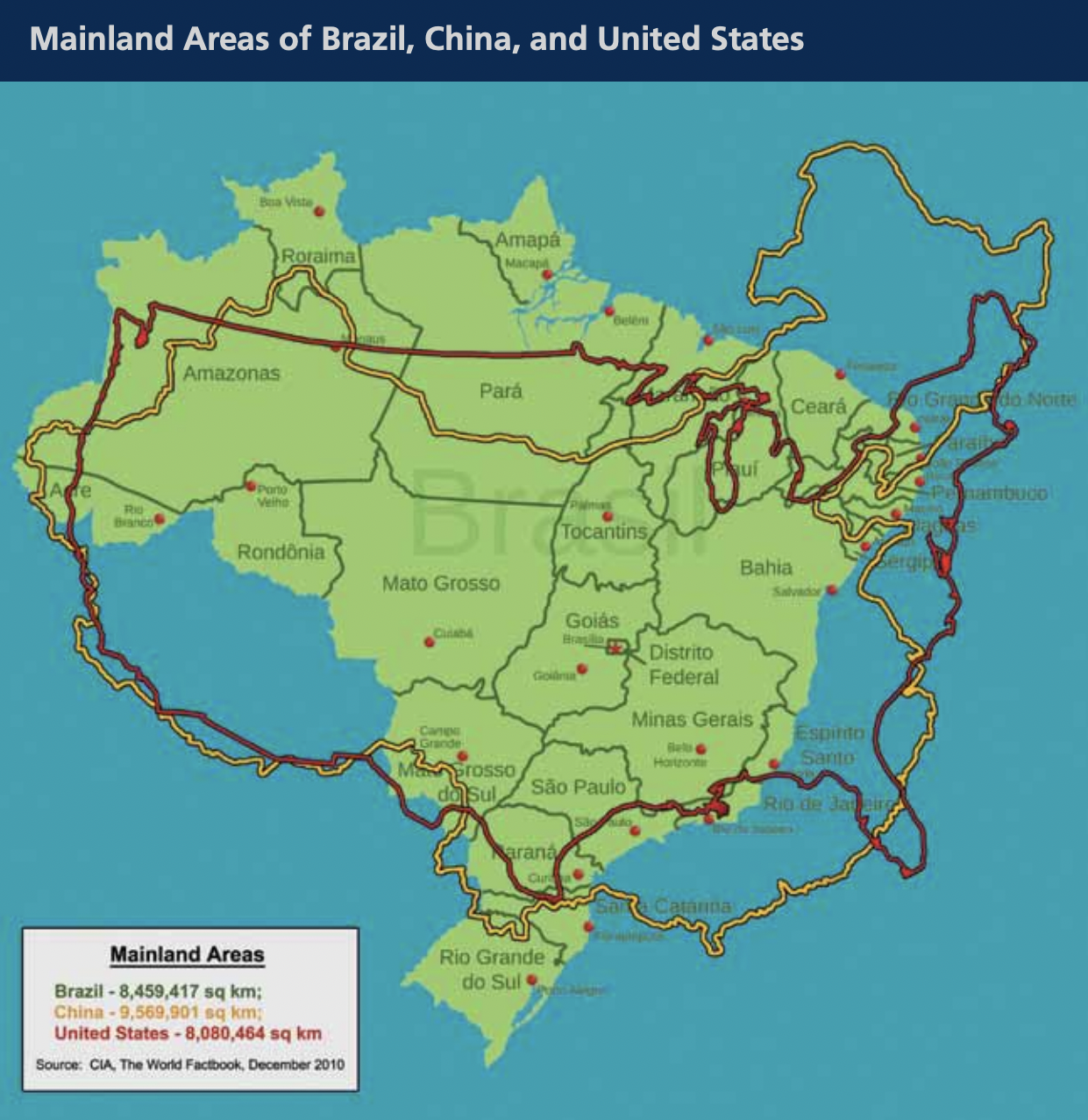

Brazil has long seen itself as the southern hemisphere twin of the United States. In the last few decades, Brazilian agriculture has expanded furiously, plowing the Cerrado with a capital intensity rivaling the earlier plundering of the American prairies. That demolition produced vast soy and corn latifundia that has put Brazil in direct competition with the Midwestern corn belts and the soy towns along the Mississippi. As in the US, Brazilian farmland expansion has gone hand in hand with state support, including a web of rail, roads, and waterways to maximize agricultural extraction for internal and export markets.

That physical infrastructure is kept running by agribusiness bosses and their cronies in parliament, who will stick around through Lula’s next term. We’ve just seen this show play out in the United States. Biden’s climate bills were critically weakened in negotiations with Senator Joe Manchin, representing the voice of oil and gas companies grown fat on a fracking boom. Likewise, Lula will have to make bruising compromises with the JBS-commandeered rural bloc of politicians seeking subsidies for agro-industry. The Workers’ Party (PT) may control the presidency, but Bolsonarists hold the largest bloc in Congress with 99 seats and 14 of 27 states governorships, while the center-right parties form the largest Senate bloc. That legislative impasse means Lula will have to pick battles from his ambitious agenda of social housing, greening agro-industry, and transitioning Petrobras, the national oil company.

The new Lula government will have to contend with homelessness, unemployment, and more than a quarter of the population living with hunger. But backed by housing movements, Lula aims to expand social housing and public-transit-oriented green urban development. Any success would serve as a model for other middle income democracies.

Crude oil is also a significant source of Brazil’s export income, not far behind soybeans. In a late-March interview with Time, Lula dismissed talk of ending national oil extraction. But a Lula government will exert more control over Petrobras, seeking more domestic refining capacity and a vision like that of European oil majors who are declaring themselves “integrated energy companies” that make renewable electricity.

COP27

Brazil’s election result and Lula’s attendance will boost the mood at the UN annual climate conference, which begins its 27th meeting on Sunday in Egypt. But the pull of Brazil’s big agriculture and oil underlines how difficult the meeting will be.

Standard agenda items relating to money won’t be easily smoothed over by rallying around familiar long-term targets and sectoral pledges. The global debt/currency crisis has prompted tougher questions around the broader financial architecture. Participants from the global South may no longer be content to quarrel over commitments within the confines of climate finance. Many developing countries are experiencing a dire mix of debt distress, high commodity import prices, climate-driven disasters, and scarce access to hard currency.

Our first newsletter explored some of the proposals to fix the widening north-south disparity in financial architecture using mechanisms, such as sovereign debt reform and IMF Special Drawing Rights. These matters are now, at last, reaching beyond the world of the Bretton Woods institutions and into UN climate diplomacy.

A thread linking the two together is “Loss and Damage,” a kind of sovereign compensation for climate-driven harms. L&D, which is distinct from climate “adaptation” because it denotes harms that can’t be managed or avoided, finally attained a place in the formal COP agenda last year, but with little promise of funds.

Loss and Damage will be harder to downplay now as Pakistan faces an historic crisis. Monsoon rains flooded over a third of the country’s land mass, in the wake of severe heatwaves and on top of a Covid-19 exacerbated debt crisis. Sherry Rehman, climate change minister, has told international and domestic media that wealthier countries with greater responsibility for planet-heating emissions need to pay up. “The bargain between the global North and global South is not working and it needs to be fixed for the global South to survive the oncoming train of climate change,” she told Dawn, adding that official climate finance takes two to three years to access.

The IMF will loan Pakistan $1.17bn of a $6bn facility agreed in 2019. But the total cost of the flooding is estimated at $15 to $30 billion. While the loan may help with immediate crisis-fighting efforts in Pakistan, it could also be just enough aid to create the appearance of acting on L&D pre-COP.

The moral case for loss and damage compensation is plain: By and large, the greatest temperature increases and most punishing storms will hit poor countries clustered near the equator that have contributed little to climate change. Yet proposals for rich countries to pay up have so far proved a political cul-de-sac.

The US in particular is wary of anything that might look like reparations or might identify vast liabilities. “You tell me the government in the world that has trillions of dollars, ’cause that’s what it costs,” John Kerry said last month.

Domestic politics constrains the US, which is only slowly edging towards enabling the World Bank to lend more, even while Fed rate rises heap more pain onto low-income countries.

To the Conference of the Parties, global South countries are bringing demands for loss and damage, the Bridgetown Agenda, and a possible debt strike by the climate-vulnerable. Can Lula build global South solidarity? How will the Biden administration approach Brazil’s moves? Instead of fearing autonomy from new Pink Tide governments, Biden should take the easy win of supporting Lula to achieve shared goals of planetary stability.

Filed Under