On August 5, 2019, Indian Home Minister Amit Shah presented the draft of the Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) Reorganization Bill in the Lok Sabha, the lower house of India’s parliament. The bill threatened to permanently alter the legal, political, and economic status of the state, sparking widespread outrage in the region and across the world. As Yamini Aiyar of the Hindustan Times commented:

The undemocratic manner in which the J&K reorganization bill was passed in Parliament, the silencing of voices of those affected by these actions, and the unprecedented move to convert a recognised state into a Union Territory (UT) —mark a rupture in India’s federal trajectory. India is now firmly on the path to centralisation of power and may well be inching toward transforming into a unitary rather than federal state.1

The bill proposed revoking the state’s constitutional autonomy, downgrading it to an Indian Union territory directly administered by the Indian government, and opening its international legal status to dispute. Most importantly, it abrogated Article 370 of the Indian Constitution, which in 1949 gave Jammu and Kashmir “special status,” including measures of autonomy from the Indian union government and the ability to grant special employment and land ownership privileges to permanent residents.

The right-wing ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) used its majority to force through the bill in both houses of Parliament. On August 6, a day following the bill’s presentation, Article 370 was repealed by Presidential order. The move was widely considered illegal by constitutional experts and the Indian Supreme Court and lacked support from J&K’s elected state government—a coalition led by the local People’s Democratic Party—which itself was dismissed by Presidential decree in June 2019. Preempting resistance in what has been the site of continuous armed insurgency against Indian rule since 1988, Shah added 35,000 armed forces to the existing 308,000 stationed in J&K. Indian soldiers stretched barbed wire across neighborhood exit points; the state cut mobile and internet services and imposed restrictions on movement. The lockdown served to silence Kashmiri resistance, allowing the Indian government to control the information emerging from the protests. The government crafted a narrative of Kashmiri violence and backwardness.

The centralization initiated by the bill bears powerful implications for regional development. In his speech before Parliament, Amit Shah declared that corruption had ruined the state, claiming that “only 3 families benefited from Article 370.” The government narrative held that the repeal would ultimately facilitate investment to benefit the state. But contrary to the depiction of the region as underdeveloped, chaotic, and in need of governance, Jammu and Kashmir boasts one of the lowest poverty rates in India.

Jammu and Kashmir’s distinct distributional history is intimately linked to its regional autonomy. It was J&K’s special status that empowered the state government to implement the most radical land reform policies in the nation post-Independence, in which over 90 percent of land owned by landlords was redistributed. These unrivaled policies laid the foundation for the state’s later development success.

Measuring development in Jammu and Kashmir

Despite Shah’s assertions, J&K has consistently been ranked among the highest across most developmental indicators. Examining Census of India and Planning Commission data from 2011, H.A. Drabu notes that “the relative inequality, the distribution of income as well as consumption in J&K are all much more evenly spread across the population.”2

Figures from the 2012 Reserve Bank of India report (the most recent report available) show the absolute poverty rate in J&K was 13.1 percent, compared to 37.2 percent in India. With an overall Gini coefficient of 0.24, J&K has significantly less income inequality than India, which has a Gini coefficient of 0.34—making it one of the eleven most unequal countries in the world.3 These figures help make J&K “one of the most egalitarian sub-national economies in the country.”4

The percentage of indebted households in J&K was estimated at 29.5 percent for rural areas and 17.9 percent for urban areas, compared to 31.4 percent and 22.3 percent, respectively, at the all India level in 2017. In the same year, the percentage of indebted households in J&K was estimated at 29.5 percent for rural areas and 17.9 percent for urban areas, compared to 31.4 percent and 22.3 percent in India.5 According to Drabu, “Households in J&K [had] the second lowest incidence of indebtedness in the country. Combining the incidence of indebtedness and the average value of assets per household, J&K, with a debt-to-asset ratio of less than one, is one of the best in the country.”

With low poverty and indebtedness, Jammu and Kashmir scores higher than India on average on other Human Development Indicators, including life expectancy at birth, infant mortality rate, maternal mortality rate, household access to clean drinking water, household access to sanitation, nutrition, and prevention of homelessness and child marriage.

| Key HDI Indicator | India | Jammu & Kashmir |

|---|---|---|

| Sex ratio of the total population (females per 1,000 males) | 991 Rural 1,000 | 972 Rural 978 |

| Sex ratio at birth for children born in the last five years (females per 1,000 males) | 919 Rural 927 | 922 Rural 928 |

| Households with electricity (%) | 88.2 Rural 83.2 | 97.4 Rural 96.3 |

| Households with an improved drinking-water source (%) | 89.9 Rural 89.3 | 89.2 Rural 85 |

| Households using improved sanitation facility (%) | 48.4 Rural 36.7 | 52.5 Rural 45.9 |

| Mothers who had antenatal check-up in the first trimester (%) | 58.6 Rural 54.2 | 76.8 Rural 74.1 |

| Mothers who had at least four antenatal care visits (%) | 51.2 Rural 44.8 | 81.4 Rural 78.8 |

| Average out of pocket expenditure per delivery in public health facility (Rs.) | 3,198 Rural 2,947 | 4,192 Rural 4,104 |

| Children age 12-23 months fully immunised (BCG, measles, and three doses each of polio and DPT) (%) | 62 Rural 61.3 | 75.1 Rural 72.9 |

| Children under five years who are stunted (height-for-age)12 (%) | 38.4 Rural 41.2 | 27.4 Rural 28.8 |

| Men who are literate (%) | 85.7 Rural 82.6 | 87 Rural 86.5 |

| Women who are literate (%) | 68.4 Rural 61.5 | 69 Rural 65.4 |

| Institutional Births | 78.9 Rural 75.1 | 85.7 Rural 82 |

| Women whose Body Mass Index (BMI) is below normal (BMI <18.5 kg/m2) (%) | 22.9 Rural 26.7 | 12.1 Rural 14.1 |

| Men whose Body Mass Index (BMI) is below normal (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2) (%) | 20.2 Rural 23 | 11.5 Rural 13.6 |

| Anaemic children between 6-59 months (<11 gidl) (%) | 58.4 Rural 59.4 | 43 Rural 44.1 |

| Pregnant women age 15-49 years who are anaemic(<11g/dl) (%) | 50.3 Rural 52.1 | 38.1 Rural 39.4 |

| Infant Mortality Rate (per thousand live births) | 41 | 32 |

| Under five mortality rate (per thousand live births) | 50 | 38 |

| Life expectancy at birth(in years) | 67.9 | 72.6 |

These figures from the Indian government-supported National Family Health Survey indicate that J&K leads India in twenty out of twenty-two of the key indicators. With a Human Development Indicator (HDI) score of 0.53, the state is well above India’s average HDI score of 0.47.6

“New Kashmir”

Jammu & Kashmir’s legal autonomy and unique political circumstances have been key to its development achievements. When India became an independent nation on August 15, 1947, J&K was characterized by feudal land ownership, an abysmally low literacy rate of 5 percent (compared to 18.3 percent in India), and a life expectancy of just twenty-seven years. Like many other princely states in India, it was given the choice to join either India or Pakistan, but the territory’s leader Maharaja Hari Singh favored independence and remained sovereign until October 1947. The 1947 tribal invasion from Pakistan dramatically shifted the political calculus. The Maharaja was forced to appeal to India for military assistance, in exchange for which the Indian government demanded that J&K join the Dominion of India. During the ensuing Partition, thousands of Muslims from Jammu were killed by the Maharaja’s Dogra mercenaries, with assistance of the Hindu nationalist Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS).7 The Maharaja signed Article 35A of the Indian Constitution, which later became Article 370, and negotiated the terms of membership so that J&K could draft its own Constitution as well as retain the right to ratify all Indian laws through the state Assembly. This granted the newly semi-autonomous state the tools to craft a distinct legal foundation for its development policy.

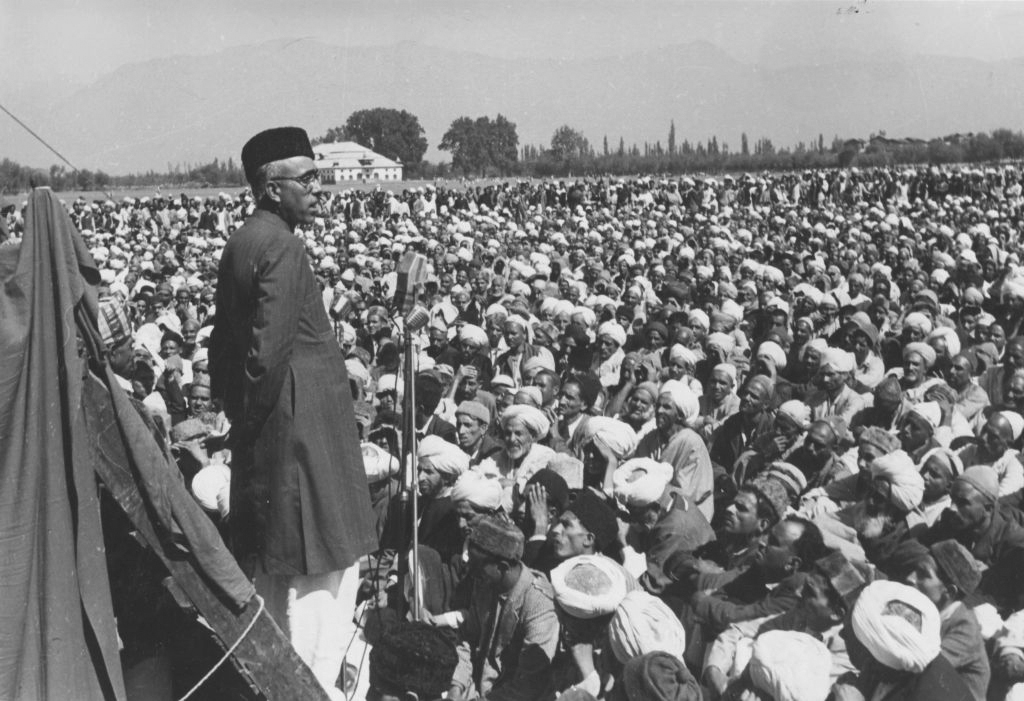

The invasion’s aftermath led to an interim emergency administration headed by Sheikh Abdullah, who was supported by Indian Prime Minister Jawarahal Nehru. The Maharaja was soon forced to leave Kashmir; he spent the remainder of his life exiled in Bombay, with Abdullah left to serve as the first Prime Minister of J&K from 1947 to 1953. The emergency administration was granted sweeping powers, giving Abdullah the unique chance to implement his party’s communist-inspired agenda, unfettered by the possible political fallout as state elections were only held in 1952. The Maharaja and his old feudal loyalists had little influence—military support from New Delhi gave Abdullah effective control of power, and a close personal relationship with Nehru further bolstered his position. The monarchy was formally abolished in 1952, eroding resistance from landlords on the ground. The weakened political position of landowners combined with the state’s legal status thus paved the way for land reforms.

Abdullah’s key alliances extended beyond Nehru. Influenced by communist ideals and his friends B.P.L Bedi and Freda Bedi, Abdullah made asset redistribution a primary objective. The Bedis, committed communists active in the “Quit India” movement, were closely allied with Abdullah and his party, the National Conference. Borrowing ideas from Stalin’s constitution in the Soviet Union , B.P.L. Bedi led the drafting of the National Conference’s 1944 manifesto, “New Kashmir,” which was meant to modernize the then princely and semi-feudal state.8 The radical directive principles promoted not only a planned economy, but also the abolition of the “big private capitalist” and “landlordism.” The J&K state Constitution adopted specific provisions of the document, including:

the promotion of the welfare of the mass of the people by establishing and preserving a socialist order of society wherein all exploitation of man has been abolished, and society wherein justice—social economic and political—shall inform all the institutions of national life.

Legal autonomy and development

J&K’s special status meant that unlike other states, the region’s land policies were not restricted by Article 19 of the Indian Constitution, which prohibited land redistribution without paid compensation to landowners and enshrined the right to property. Even in West Bengal and Kerala, where communist parties held power for several decades, land reforms were limited, with costs of compensation serving as a major barrier. In both states, only a small percentage of land was distributed—66,000 out of 4 million acres in Kerala,9 and one million out of 13 million acres in West Bengal.10 In most other Indian states, powerful landlord lobbies successfully blocked land reforms, leaving exploitative ownership structures in place. This led to persistent poverty, malnutrition, and indebtedness, with caste and landed hierarchies remaining firmly in place.

Article 370 gave unparalleled legal powers to the state government and served as a shield against Article 19, with a sub-clause of J&K’s constitution preventing the land reforms from being annulled by the Indian Supreme Court. In total, successive state governments transferred the ownership rights of more than 620,875 acres of land to the tillers, out of a total of 687,500 acres of land owned, without any compensation for landowners.11 More than 90 percent of all land under feudal landlords was redistributed to landless tillers. The effects were immense: according to the 1941 Census of India, agriculture supported 87.5 percent of the total population in these areas, and land redistribution substantially weakened the territory’s landed aristocracy. The district-wise allocation of land was as follows (figures in kanals12):

| Kashmir | |

| Srinagar | 20943 (least in Kashmir) |

| Budgam | 736188 (most in Kashmir) |

| Anantnag | 214660 |

| Kulgam | 40833 |

| Bandipora | 70988 |

| Kupwara | 131844 |

| Ganderbal | 55351 |

| Baramulla | 69336 |

| Shopian | 55903 |

| Pulwama | 108152 |

| Ladakh | |

| Leh | 17614 |

| Kargil | 12608 |

| Jammu | |

| Jammu | 777508 (most overall) |

| Doda | 158271 |

| Reasi | 559981 |

| Kathua | 447825 |

| Udhampur | 476543 |

| Kishtwar | 63332 |

| Samba | 120405 |

| Ramban | 166955 |

| Rajouri | 658939 |

| Poonch | 3462 (least overall) |

| Total | 4967641 |

Drabu notes, “It is because of land reforms that our poverty ratio is 10 percent, which is less than half of all India level; our indebtedness at 12.67 is nearly one third of the national average [and] there is a near absence of landless labor, less than 2 percent of our workforce.” Other development indicators—including the region’s vast improvements in literacy and life expectancy over the second half of the twentieth century—can be tied to the post-1947 policies that targeted inequality. In addition to land redistribution, the Distressed Debtors’ Relief Act of 1950 abolished all non-commercial private debt, breaking the stranglehold of the moneylender system which charged exorbitant rates of interest and imposed debt slavery on the rural poor. The debt conciliation policy ensured that the land redistributed would not be mortgaged by farmers in lieu of debts. No other state in India has passed legislation targeting indebtedness as comprehensively. Moneylenders across the country still exploit the poor “with interest rates as high as 120 percent,”13 though limited legislation to write off farmer’s loans was passed in Tamil Nadu in 1936 and in Haryana in 2007.

Because the autonomous J&K Constitution excluded the right to property, landlords initially had little recourse to challenge the initial land and debt reforms. In 1954, when the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court of India was extended to the state, the bulk of the land had already been given to the tillers, and landlords could not afford long and costly legal battles. The reforms’ political effects were tremendous—they catapulted Sheikh Abdullah’s status across the state, and he soon came to be seen as the savior of tenant farmers. To this day, the Jammu & Kashmir National Conference maintains a loyal rural voter base.

After August 5, 2019

Recent tax policies, “anti-encroachment” measures, and quota systems targeting residents are only the latest in a long history of Indian government attempts to control the nation’s only Muslim-majority state. Through what has been termed a “civilizing mission,” successive liberal administrations sought to “show Kashmir’s overwhelmingly religious Muslims the light of secular reason, by force if necessary.”14 In 1953, Sheikh Abdullah was imprisoned on charges of political conspiracy. Conservative governments attempted to curb Kashmir’s autonomy, dismissing elected state governments and curtailing financial and legal authorities through twenty-seven constitutional orders between 1964 and 1975. In 1987, the federal government rigged state elections on a mass scale, prompting the armed insurgency that launched in 1988. The Indian government then imposed direct rule in 1990, with state Parliamentary elections only resuming in 1996. Kashmir was transformed into the most militarized region in the world. With the victory of Narendra Modi in 2014, the BJP seized the opportunity to build on this political tradition.

The Reorganization Order threatens the core identity of Jammu and Kashmir. “Israel style settlements” bode displacement, reduced access to employment for the local population, and worsening violence.15 Although the BJP argued that eliminating Article 370 would stem militancy, youth recruitment has persisted. Ipsita Chakravarty notes, “Ceasefire violations on the Line of Control doubled in 2019 from the year before . . .The first six months of 2020 have been one of the most lethal periods in recent years, killing 118 militants and 26 security forces.”

Additionally, with the repeal of 370, independent statutory bodies that dealt with women’s rights, children’s welfare, disability rights, human rights, and public accountability are now in danger of elimination. J&K was previously the only state in India to reserve half of its medical seats for women, thereby improving women’s health access. The lockdown’s movement and internet restrictions further impeded access to education and healthcare, and the Kashmir valley’s economy lost ₹40,000 crore. 500,000 Kashmiris lost their jobs due to closures.16 The Covid-19 pandemic only intensified economic distress.

Jammu and Kashmir’s dramatic turnaround after 1947 signals the success of a radical redistributive policy. The formerly feudal territory enacted the most extensive redistribution policies in the nation, but its gains in development occurred alongside the restriction of political choice. Understanding the J&K’s developmental trajectory—and the legal autonomy that enabled it—offers a glimpse of the Reorganization Order’s long-term significance. The residents of Jammu and Kashmir have been further disempowered, leaving the state’s resources open for plunder. With the purported aim of “opening up” Kashmir to India and the world, and under the guise of “development,” the pursuit of investment and militarized control now reigns.

Aiyar, Yamini, “India’s March towards Centralisation,” Hindustan Times, August 11, 2019.

↩Drabu, H. A. “Was Special Status a development dampener in J&K?”, Livemint, August 7, 2019.

↩The Commitment to Reducing Inequality Index measures government action on social spending, tax, and labor rights, the three areas international experts say are critical to reducing inequality. India ranks 147th out of 157 countries in this index because of massive government failures in collecting tax from the richest, extending public spending and providing entitlements to the millions who work in the agricultural and unorganised sectors. In its report on CRI globally, Oxfam International described India’s neglect in addressing inequality as “a very worrying situation given that it is home to 1.3 billion people, many of whom live in extreme poverty.”

↩Drabu, H. A. “Was Special Status a development dampener in J&K?”, Livemint, August 7, 2019.

↩National Sample Survey Office “NSS Survey 71st round, August 2016, Schedule 25,” New Delhi: Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation Central Statistics Office, Research & Publication Unit, 2017.

↩Planning Commission, India Human Development Report, New Delhi: Government of India, 2011.

↩Christopher Snedden (2001), “What happened to Muslims in Jammu? Local identity, ‘the massacre of 1947’ and the roots of the ‘Kashmir problem,’”South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies, 24:2, 111-134.

↩Whitehead, A., “The Rise and Fall of New Kashmir,” in Chitralekha Zutshi, ed., Kashmir: History, Politics, Representation, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2018, p. 75-76.

↩Jayadev, Anishia and Huong Ha, “Land Reforms in Kerala: An aid to ensure sustainable development” in Huong Ha ed, Land and Disaster Management Strategies in India, New Delhi: Springer, 2015.

↩UNDP, West Bengal Human Development Report, 2014.

↩Beg, Mirza Mohammad Afzal, On the Way to Golden Harvest: Agricultural Reforms in Kashmir, Government of Jammu & Kashmir, Jammu & Kashmir, 1951.

↩A kanal is Jammu and Kashmir’s official unit of measurement of land. One kanal is one eighth of an acre.

↩Qazi, M “Inside the world of Indian money lenders,” The Diplomat, March 31, 2017.

↩Wade, F., “The Liberal Order Is the Incubator for Authoritarianism: A Conversation with Pankaj Mishra,” The Los Angeles Review of Books, November 15 2018.

↩The union government claimed that private investment was previously hindered by Article 35A (the restrictions it imposed on land ownership by non-residents. But before August 5, land for industry was available for a ninety-year lease (renewable further) on easy terms by the Jammu and Kashmir government, much like other state governments across India.

↩Kashmir Chambers of Commerce and Industry.

↩

Filed Under