In terms of its size, dynamism, and degree of global integration, China’s market economy is extraordinary. Though it’s known officially as a “socialist market with Chinese characteristics,” its market features far predate the 1978 decision on “reform and opening.” The reformist Chinese growth model has always been characterized by a distinct pragmatism. This involves integrating macro programming and regulations, a mix of public and private ownership and control, market allocation to various degrees of resources and distribution, bureaucratic cronyism in productive and business organizations, and international “free trade.”

This model is the outcome of decades of adaptation and innovation. While much has been written on pre-nineteenth century Chinese economic strategy, far less attention has been paid to the wartime fiscal and monetary experiments undertaken during the Communist Revolution. In an effort to rectify this oversight, I review revolutionary economic policy from the 1920s until the 1940s, reflecting on its theoretical and institutional implications.

The pacified empire

The unified Qin–Han state originated from an amalgam of the annals of Warring States around the same time as the rise of Rome in the Western Hemisphere. While the Roman Empire fell in the fifth century, imperial China outlived it and subsequent empires. This longevity was in part rooted in its socioeconomic arrangements. Trade had flourished early with extensive internal and external networks across continental and maritime expanses, encompassing numerous silk roads and transportation routes to reach many societies and cultures.

Prior to 1800, the Chinese, Indian, East Asian, Southeast Asian, and Arab economies were weightier producers than their counterparts elsewhere.1 In The Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith recognized that “China is a much richer country than any part of Europe,” despite signs of stagnation.2 Instead of an industrial revolution, the Chinese accomplished an “industrious revolution,” argued Giovanni Arrighi, consistent with a Smithian path of “natural progress of opulence” rather than the “unnatural and retrograde” European path of interstate rivalries over power and colonial extraction.3 China at its splendor was so wealthy, thanks to regions like the Yangzi Delta, that while Europe was compelled to adopt machines to cut labor costs, “China didn’t ‘miss’ the industrial revolution—it didn’t need it.”4

By the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, China had become the largest trader on the silver standard, contributing to the emergence of global capitalism but without transforming into a colonial empire. In a review of Chen Huan-chang’s 1911 The Economic Principles of Confucius and his School, John Maynard Keynes noted China’s trimetallic system dating back to “the remotest times,” observing that in the use of paper money, the Chinese “long anticipated other peoples.”5

Accordingly, “cooperative banks” were invented around 220 AD, and, in subsequent centuries, developed into government and shadow banking of coins, notes, bills, bonds, and “flying money”—money certificates to “control the price of all commodities.”6 In place of the liberal legal institutions, credit systems, and public budgeting that characterized early modern Europe, the Chinese economy operated through informal arrangements of properties and contracts, claims and debts, rights and liabilities, which relied on personal and family ties, townsmen associations, and other private partnerships.7 Ingenious transactions and lending in China’s commercial centers notwithstanding, underdeveloped financial infrastructure and stimuli of the economy came to be a competitive disadvantage. The “pacified empire,” Max Weber remarked, was a contrast to war-financed “varieties of booty capitalism” in Europe, where states enriched themselves “through war loans and commissions for war purposes.”8

Economic difficulties and political turmoil around the transition from Ming to Qing were an instance of the financial weakness of the Chinese imperial monetary system. Under Europe’s financial hegemony, major inflation in China was directly caused by the depletion of silver inflow in the seventeenth-century world crisis.9 En route, European ocean vessels linked American cotton and mining products derived from slave labor and trade from Africa with the Chinese-Indian-Arab markets. Gunder Frank recounts this gigantic trading triangle in which the Europeans took out American silver to “buy themselves tickets on the Asian train.”10 Finding itself a “bottomless pit” for the influx of American silver and its monetization, China became dependent on foreign currency supplies and offshore exchange rates. This was not only economically but also politically costly, as the monetary arbitrage from the externally forged silver standard undermined the Chinese state. Foreign banks and other financial institutions had also come to China since the late-nineteenth century, hence the formation of a Chinese comprador class of financiers and financial brokers who locally facilitated imperialist super profits and rents.

Lacking the capitalist mechanisms of creative destruction and limitless accumulation, the premodern Chinese economy followed its own patterns of evolution—or involution, as some economic historians prefer to characterize it. Examples of its working methods are many: state depots of an “ever normal granary” (changpingcang) to balance seasonally fluctuated grain prices and regional price differentials; periodic government procurement of other essential goods in preparation for disaster relief and the easing of lean time market pressure; and recurrent reforms to unify taxation, regulate commerce, and calibrate competition. These ideas and institutions, refined over successive dynastic regimes, have been studied by economists, historians and sociologists in a growing scholarship of comparative economic history.

Among the most well known classics is the Guanzi (seventh century BC). Two millennia before the advent of classical and neoclassical economics, this economic-philosophical text, believed to be a reflective record of the economic principles discussed between the Duke of Qi and his prime minister Guan Zhong in the Chun-Qiu period, can be read contemporarily. The core argument is a “heavy-light” distinction in the hierarchy of importance attached to goods in their production and trade, which determines the need for, and techniques of, official pricing. To ensure adequate supply of the “heaviest” items, for example, the government must “stabilize the price of grain in order to stabilize the overall price level and the value of money.”11 On Salt and Iron is another famous classic, a collection of documents on the salt and iron debate between the realist Guanzians and the moralistic Confucian literati. At a West Han conference (81 BC), the former group as policy advocates promoted state intervention as an obligation for economic prosperity and price stability. The latter group, on behalf of aggrieved producers and merchants suffering predatory officials, lamented a foregone age of pliable governments.12

Following the Wu emperor (141-87 BC) who endorsed rounds of monetary reform, central monopolies of salt and iron developed, and became a staying policy. The state reined in fierce competition among the large landed and mercenary interests. These events were analytically narrated in such writings as “treatise on foodstuffs” and “usurers.”13 Ban had incorporated what was earlier documented in the “biographies of usurers” (book 129) and “a treatise of leveling” (pingzhun shu, book 30) by Si Maqian in the Records of the Grand Historian. The pingzhun officials were assigned to the balancing act of market stabilization by organizing “selling [crops etc.] where and when they are scarce and dear, and buying them where and when they are bountiful and cheap.” This particular conception and measure of pingzhun, together with the heavy-light differentiation based priorities, are perhaps the most outstanding of the ancient economic wisdoms in laying the policy foundation of China’s future economic performance.14

Power and adaption

In contrast to China’s pre-communist economic history and thought, wartime communist economic management has been largely neglected outside of China. The fusion of old wisdoms and novelties in this unique experience, however, deserves greater attention.

The story begins with the first tide of the labor movement in the early 1920s. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and its Trade Union Secretariat resolved to amalgamate political and economic class struggles. Its earliest experiment with shareholding cooperation was a self-managed cooperative for the coalminers and railway workers in Anyuan, Hunan, in 1923. This effort initiated the use of membership “red shares” and coupons. Mao Zemin, a younger brother of Mao Zedong’s, was twice its general manager. After the Guomindang (GMD) right wing slaughtered tens of thousands of communists and sympathizers in 1927, the CCP retreated from urban agitation and recruited at the rural margins. In these areas, cooperative farms, workshops, credit, trading and remittance networks developed widely, with voluntary participants as shareholders of specialized or multifunctioning cooperatives.15

The cooperatives were also a vehicle of mutual aid and political education. Yu Shude, a party veteran since 1922, recognized that “creating collective power through cooperation” was a means for the vulnerable majority of the Chinese population to forge political ties. The ultimate aim was to replace private property, but “before the new social organization can be established, cooperation is the rescue for petty producers.”16 This idea was popular, and it echoed in the non-communist reform movements for Rural Reconstruction and Popular Education.17 It later accented the national rural cooperative campaign of the 1950s and was revived through the “Marxist theory of cooperation” to legitimize collectivization in the early 1980s.

The uneven nature of Chinese development and the temporal-spatial specificities of the Chinese revolution bore significant implications for the revolution’s economic orientation. State building in the People’s Republic thus began in the rural peripheries decades before the CCP came to national power, with the strategy of “encircling the cities from the countryside.” The revolutionary bases were created and expanded in discrete territories to break the weak links of counterrevolution. This was possible because imperialist powers and their local pillars in China were divided, and conflicts among the warlords were pervasive. In his analysis of how the small, separatist red regimes could survive privation and isolation, Mao highlighted semi-coloniality and the indirect nature of imperialist rule.

In the absence of an integrated national market, the red forces could carve out their own territories around the borders of several provinces away from the counterrevolutionary strongholds. However slim, the opportunity gave rise to the daring endeavor to build the “armed independent power of workers and peasants” as a “movable counter power.” Ultimately, the revolutionaries sought to aggregate a historical bloc out of this “state within the state.”18 During the next waves of revolution, they were vindicated, as a single spark did start a prairie fire.

Mao was writing in the mountainous provincial edges where the first Chinese red army regiments battled to win a primitive home as the cradle of an armed revolution. The Jinggang base was the first among communist local regimes to survive attacks by extreme adversaries. For the base, economic viability meant life or death.

Central to the party’s minimum program was land revolution. This revolution was of epochal significance in overturning China’s thousands of years old “feudal” (a borrowed term in the communist vocabulary) order, which entailed the polarity of land concentration and landlessness, the collusion of landlords and bureaucrats, widespread miseries and stalled modernization. The communists sought to alter the division between capital accumulation and productive investment which resulted from land purchases and usury. By the same token, as the landed, money-owning, and power-holding classes were jointly destroying the agricultural base of Chinese society, the country’s legendary but stifled productive forces were invigorated thanks to the redistribution of land.

In the following two decades, the CCP carried out this effort while remaining sensitive to changing political circumstances. Policies on land redistribution or rent reduction engaged the regional communist governments, the red army, the trade unions, peasant associations, women’s federations, and other mass organizations. Without the economic conventions directed by a landed and patriarchal gentry, the party prioritized productive self-sufficiency, popular livelihood and military provision.

Trade was a predominant priority for impoverished red regions. Tungsten mining in the Jinggang mountains, for instance, was an indispensable source of income, hence the trading of ore with non-local merchants in return for certain daily necessities and badly needed medicines for injured soldiers. Over a series of military victories, the Chinese Soviet Republic was declared in the town of Ruijin in Jiangxi from 1931 to 1934, which commanded dozens of border region soviets nationally. This was a turning point in communist state crafting.

But these enclaved regimes had to quickly develop commercial and financial ties. The joint-stock Zhicheng Bank in Shenyang is a good example of efforts to accomplish this. The bank was a vital asset of the party struggling to provide the isolated Northeastern Anti-Japanese Aggression Volunteers with medical and arms supplies.19 Just as remarkably, the party ran a commercial station in Hong Kong as a mission facility in the lifeline of its base areas and guerrillas. Qin Bangli, a banker in training and brother of Bo Gu, politburo general secretary from 1931 to 1935, was a “capitalist in practice but communist by conviction” who “scrimped every Hong Kong dollar he could” from business for the revolution while his family lived in a bare rented apartment.20

Despite a battle for self defense, the red regimes were repeatedly overrun, cut off from one another, and economically strained. The central soviet experienced dramatic shortages and inflation, and consequently its authority had to resort to barter borrowing in 1934. Losing Ruijin to the GMD military extermination campaigns in the same year, the communists embarked on the epic long march and relocated their counter-state headquarters in Yan’an in northern Shaanxi (Shanbei). A special troop of the long marchers shouldered the soviet treasury in gold, silver, banknotes, and minting machines trekked a perilous 6000-mile journey.

The relaunch of the soviet central bank in 1935 was based on these capital funds and the reserves of the existing local soviet bank. Soon after the three red field armies joined forces in Shanbei in 1936, they were restructured under the second CCP-GMD united front of the national resistance war and fought the Japanese and their puppet army in the most arduous conditions. By the end of 1945, the communists were in control of vastly enlarged “liberated areas” of ninety million people, or one fifth of the national population behind the enemy lines. Gathering momentum during the civil war, the now renamed People’s Liberation Army (PLA) took offensives to liberate north China and by the early summer of 1949 crossed the Yangzi river to seize the south. The US-backed GMD forces crumbled and fled to Taiwan.

The communist managers strove to foster subsistence and commercial agriculture as well as rudimentary industries with a facilitating ownership structure, schemes of subsidies, tax breaks, and other incentives. The red army depended mainly on resources from the battleground but also ran military clothing and munition factories. The “campaign for mass production” in the Shan-Gan-Ning border region from 1940 to 1946 engaged all the government and army units; party and army leaders were each assigned quotas of labor or products to fulfill. This movement ensured that the main communist regional powers would be economically viable. It also initiated a proud tradition of self-reliance and the army’s productive and constructive roles in peacetime.

The huge Huaihai campaign in the winter of 1948–49 also demonstrated how the sweeping land reform and related socioeconomic policies decisively changed the outcomes of the war. Thanks to the enrollment of recently landed peasants, the PLA was able to defeat the far better equipped GMD army. Division after division of the GMD army defected to the PLA on the spot, choosing to fight for their own land.

Undoubtedly, the fact that the communist local blocs had sustained themselves since the Yan’an era, with some even growing into economic strongholds, helps explain their success. They selectively reappropriated methods from a splendid civilizational tradition and invented their own. A most salient example was the purchasing of harvest in times of abundance and its distribution during lean times. Salt monopoly had also been adapted to manage the market and secure revenue. Though they lack a systematic economic ideology, these policies captured and nurtured market opportunities for common economic life, especially in trade within and beyond their borders.

Regional communist fiscal and monetary policies

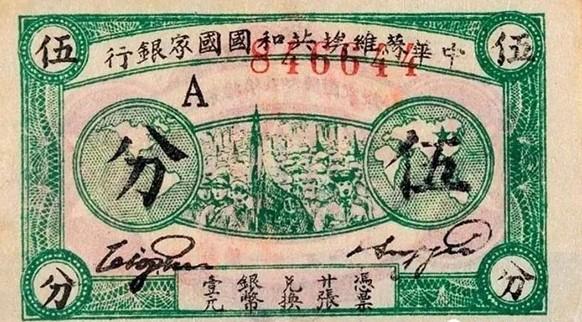

The communists initially used portable mining machinery to strike coins as the circulating subsidiaries to silver dollars. These became the standard national currency. Although the images appeared crude (see the portraits meant to be of Lenin below), “what these coins may have lacked in appearance, they made up for in integrity.” That is, the communists were honest in their dealings with the peasants, and ensured that their coinage maintained good weight and fineness—in contrast to alternatives which had varied weights and qualities.21

This applied to the earliest red paper notes as well, which, despite a ragged surface, were promised at full value. Mao Zemin, now the Governor of the Chinese Soviet State Bank founded in 1931, together with Lin Boqu and Deng Zihui, Ministers of Economy and of Finance respectively, devised an independent regional money called guobi in July 1932. With the aim of creating a unified financial system, the Guobi was declared the only acceptable currency for taxpaying and other formal payments.

The bank issued public bonds and opened a range of banking businesses of deposit, mortgage, loan, credit funds, bill discount, and remittance in support of the local economy. To strengthen the newly instituted central treasury and secure a source of revenue for fiscal and military expenditures, the financial authority directly operated a state mining company. Most impressively, it also pioneered special trade zones to bypass the anticommunist embargo half a century before China’s reform-era special economic zones. Encouraging the export of cheap local products like grain, timber, paper, and ore, while importing locally wanted goods, the “state bureau of foreign trade” set up multiple offices and warehouses alongside the borders between red and white jurisdictions.

The market logic and contradictions within the white regimes thus combined to generate a commercial boom in such places. The neighboring Min-Zhe-Gan soviet also used secrete transportation routes with armed protection and invited outside merchants into its internal markets to boost trade. Its regional bank successfully made government offerings and was able to financially assist the central soviet.22

In January 1935, the long marchers entered the small city of Zunyi in Guizhou and were stationed there for merely two weeks. They injected guobi brought from Ruijin into the market right away, pegging it to salt, the scarcest local commodity. Backed by the salt reserve seized from the warlords, the “red army notes,” as they were then dubbed, were received as “salt notes.” The purchasing power of the notes for salt and other basic goods was instantly stronger than any other currencies in the local market. Meanwhile, the exchange of red army notes with silver dollars was guaranteed by the soviet bank.

The result was immediate and by any account a miracle. With its evident credibility, the new currency stimulated the market, aided the poor, and replenished supplies for an exhausted army. Before leaving the city, the bank opened a number of emergency stores for people to quickly use up their red army notes on materials or silver dollars, achieving almost complete withdrawal of the currency.23 Unsurprisingly, the red banks which already existed in Shanbei had also pegged their currencies to salt. The shared tactic of salt monopoly continued after the arrival of the central soviet.

In 1937, the communists formally launched their Shan-Gan-Ning Regional Bank under Cao Jvru’s governorship as the new soviet state bank replacing the Northwestern Branch under Lin Boqu since 1935. Confronted with critical economic and fiscal challenges in a poverty ridden region, and upon the issuing of the new border region banknotes or bianbi in various denominations on paper or cloth, Mao telegrammed the party’s policy leaders on August 17, 1938. He underscored monetary policy principles in the prolonged war against Japanese invasion: local base currency stability, avoidance of oversupply and hence depreciation; sufficient bank reserves in kind as well as in Japanese puppet notes or weibi and the GMD national fabi; efficient external trade; and sustained army supply. The key was to “keep the value of our regional notes equivalent to or above the exchange rate of Japanese money.” Minor and less dependable currencies were also to be cleared out.24

The “foreign” currency of weibi was held as the secondary reserve because “foreign trade” with the Japanese occupied areas was unavoidable for both importing essential industrial and consumer goods and shielding the bianbi against too much fluctuation. As for the fabi, given its domination in the national market as a relatively strong currency backed by the dollar and the pound (after the silver standard belatedly elapsed in China in 1935), it was also a necessary reserve for trade across red-white boundaries.25 After the January 1941 Wannan Incident in which the communist New Fourth Army was unexpectedly attacked and nearly annihilated by the GMD, and with the Japanese occupiers pouring billions of weibi into the market to devalue the fabi, the communists had to alter their monetary policies.

Each border region administered its own banking and taxation systems to promote local businesses while countering hostile market manipulations. The regional banks and tax regimes were relatively autonomous in their relationship with Yan’an, due to sheerly uneven economic conditions across regions and individually specific situations in the midst of war and revolution. As the institutions of the state within the state, they constituted a system separate from the national economic and financial jurisdiction. These institutions served as the guardians and facilitators of local economic resilience and hence the viability of the revolutionary bases.

In the Shan-Gan-Ning region, government trading companies, such as the mainstay Guanghua Store26 and many cooperative traders, participated in the “financial warfare” waged to defend the bianbi. They furnished vouchers or cash coupons tied to the red money. To strike fair distribution between revenue and tax burdens, the Jin-Cha-Ji border region introduced and amended its cumulative tax rules in the early 1940s. Party leaders and dispatched offices worked painstakingly to design a system of enhancing state fiscal capacity without overburdening common taxpayers.27 To uphold the value of jinanbi issued by the Jin-Ji-Lu-Yu region’s Jinan Bank, the regional government designated “foreign trade” denominated in it as the standard currency, and price control was instrumental for weibi holders to pay more for the same goods.28

The odds, however, were enormous, and the bianbi did devalue on occasion. Shanbei had been hit by inflation from time to time due to a war racked economy and an adverse balance of payments. The export of salt, oil and other commodities was far from sufficient to offset importing locally unavailable manufactured goods.29 The Jinan Bank was forced to inject extra notes and coins into the market to compete with the fabi and weibi which had been both banned but only ineffectively. They lingered as the bianbi was volatile. To contain the damage, the regional government kept the window of currency exchange legitimately open, while implementing ‘gradient’ rating differentials between the region’s central and peripheral areas. This move at least protected the value of the jinanbi in the core market of the red region and its assets and stocks.30 A more effective way developed only later in the Shandong revolutionary base where the established monetary standards were resolutely abandoned.

The Shandong regional Bank of Beihai, established in 1938, had since developed a cluster of divisions alongside the communist military advances in East China. The bank treated commerce as a weapon in the communist hands to integrate production, trade, and finance under a sustainable money and pricing regime.31 Xue Muqiao, chief financial advisor to the regional government in 1943–47, led an expert team to end the constant inflationary threats. The diagnosis was of a persistent inflow of weibi and a collapsing fabi. The Beihai Bank’s beihaibi or beipiao had already been declared the sole base currency in 1942, along with the financial authority’s stated mission of “issuing the kangbi, supplanting the fabi, and prohibiting the weibi.” (Kangbi or “money for resisting Japan” was another name for bianbi and here Beipiao.) This objective, however, did not materialize until nearly two years later, when the government achieved two preparatory objectives: possession of a sufficient stock of essential commodities to back beipiao, and parity of beipiao’s exchange rate for external trade. Steadily earning popular confidence and positive convertibility, this regional currency was consolidated to witness “good money driving out bad money.” As public and private traders and fabi holders either spent the money elsewhere or redeemed it for beipiao, the latter’s credibility accelerated. It became the most stable and favorable currency not only locally but also in the surrounding areas.

Shandong was a model of communist regional economic governance, where farms, factories, shops, and other market actors came to flourish. Enemy currencies were expelled and trade thrived. The Shandong liberated areas became a resourceful base for the communist victory in the impending civil war. Xue explained this success through a strict limit on the quantity of circulating currencies and the red money’s overpowering market capture. “The law of ‘bad money driving out good ones’ discovered by the bourgeois economists’ could be reversed.”32 The fabi must be locally delegitimized because its ongoing cocirculation would weaken beipiao’s self-defense and material reserves.

Xue’s theory focused on the “material standard” (wuzi benwei) for paper money as opposed to the “universal gold standard.”33 As mentioned, it was decided that the primary reserve for the bianbi was to be “goods, especially industrial goods.”34 Only with such a material backing could the independently issued local currency hold on value and market confidence. Quoting Marx’s concept of money as commodities’ “general equivalent,” Xue argued that seeing the kangbi (bianbi) as “a castle in the air” without a metal foundation was mistaken. A currency could be pegged to precious metals or any hard currency as much as material goods. What mattered to the locals in the base areas was the worth of money materialized in physical rather than nominal forms. In Shandong, aside from producer goods, grain, peanuts, cooking oil, sea salt, cotton and other livelihood products were “the best guarantee” behind kangbi.

Responding to an American journalist who asked how beipiao had triumphed, Xue specified that “our material standard meant that we must monitor money supply according to the market demand. For every 10,000 yuan we issued . . . we would use at least 5,000 yuan to procure material goods.” With sufficient material reserves in place, the regional government could be a market regulator and price stabilizer by reflowing money from sales against inflation or increasing money to augment purchases and thereby neutralize deflation.35

Towards the national planning and market

The protection and development of independent markets in communist territories required the designation of local base currencies supplied in the right amount at the right times. The red banks functioned as central banks while playing a range of microeconomic roles as commercial banks as well. The Northeast Bank followed this pattern to issue and solidify its dongbeibi after Japan surrendered. The revolution took the whole region in the next few years and turned the northeast into its own gigantic industrial and financial powerhouse. Both Dongbei and Beihai banks had thrived until the end of 1948 when the People’s Bank of China came into being in Shijiazhuang, Hebei, where the CCP leadership was getting ready to enter Beiping (Beijing). Formed through the merger of red Huabei, Beihai and Northwest Farmers’ banks, the communist national bank began to issue the first set of renminbi or “people’s dollars” on the eve of the founding of the PRC.

The new state was confronted with economic chaos—acute hyperinflation, urban food shortages, and violent sabotage were symptomatic of a long mismanaged, deeply corrupt, and failing old regime. The crisis intensified with the 1948 GMD reform that introduced Golden Yuan Notes (jinyuanquan) to replace the severely depreciated fabi. Without minimal assurance in fiscal preparation and quantum of issuance, the note depreciated much faster than its predecessor and soon became nearly worthless. Relentlessly and soaring inflation directly contributed to the downfall of the GMD regime.

A famous case of communist resolve was displayed in Shanghai upon the communist takeover. In early 1949, the municipal government transported a large quantity of cereals and other basic supplies into the city, bulk buying through government retailers to hasten price increases and then flooding the market with released stocks to bankrupt hoarding speculators. Differentiating between essential or heavy and non-essential or light commodities, the former were protected through a cost-plus formula for the latter. Skillfully utilizing market instruments to simultaneously depress both inflated prices and excess cashflow, the new authority swiftly restored the value of money and economic order.36 Stabilizing the price of grain followed by intermediate consumer goods, the communists seemed to pick up on a traditional practice of purchasing the plenty to be sold in scant times.

Winning economic battles nationally allowed coordinated state actions across regions. The wartime experiences proved handily valuable for the new state to manage economic recovery (while sustaining the war effort in Korea). In the process, the communist economic strategists also flouted the logic of a neoclassical postulate by stabilizing the price level before fixing the budget deficit.37

Overcoming hyperinflation, financial breakdown, and speedy price stabilization also granted the rural powerholders a firm foothold in urban China. The enraged international ruling class had predicted that the rustic reds would not be able to manage large cities and the national economy, but this was soon disproven.

A treasure trove

The demise of the old state and society paved the way for socialist industrialization without conventional market incentives or financial disciplines. Despite policy blunders and serious setbacks, the communist undertaking of “internal accumulation” was spectacularly developmental, both in physical infrastructure and in human development.

Today, the importance of fiscal and monetary sovereignty and market stability remain crucial points of contention for developing and transitional economies around the world. Government reserves of essential goods, a public system of regional development banks, and the maintenance of a stable money supply are just some of the communist wartime policy experiments which bear contemporary resonance.

In reflecting on how the legal tender of bianbi was locally requisite forty years down the line, Xue Muqiao stressed its status as the only circulating currency vigilantly guarded in size and value. “The basic policy of monetary struggle” was to defend and consolidate the autonomy and security of the beihaibi market.38 He contemplated that this understanding should be useful for those postcolonial nations still lacking the means to counteract imperialist money printing machinery, short-term bonds, and contagious inflation. Financial integration at the expense of autonomy in a speculative and crisis-ridden global market can be perilous.39

Relatedly, the regulation of money supply continues to be debated. The provisional charter of the Chinese Soviet State Bank stipulated in 1932 that “money must be supplied in line with market demand” and “extremely cautiously” in an orderly manner, as again asserted at the second soviet national congress in 1934.40 In addition to capping the size of currency circulation as an intricate artwork adjusted to changing demands, the rates of currency exchange were also closely monitored. In the 1940s, Zhu Lizhi, one time governor of the Shan-Gan-Ning regional bank had recourse to fiscal flexibility. Reacting to a hazardous budget deficit, Zhu elevated the bar on bianbi supply and encouraged business lending and mortgage loans to both monetize the deficit and provide for entrepreneurial cashflow.41 The one-sided austere methods, as he saw it, could harm liquidity and in turn worsen inflation.42

State reserves also functioned as a price control mechanism. The material reserves behind bianbi balanced abundance and scarcity in the market and stabilized the currency through enabling government intervention. The financial authority could thus use its discretion to increase goods supply to lower prices against inflation or increase money circulation and buy in goods to hold prices against deflation. This “material standard,” set to constrain money supply and preserve the worth of unit money, was a token of communist financial governance banked on the regional political-legal power. An implication of this novelty in an age of unbridled financial capitalism could be the advantage of a strong real economy, for which the optimal fiscal and monetary means are yet to be worked out.

Frank, Andre Gunder, ReOrient: Global Economy in the Asian Age (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008), ch. 4.

↩Smith, Adam, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, [1776]1976), 30, 70–71, 210.

↩Arrighi, Giovanni, Adam Smith in Beijing: Lineages of the Twenty-First Century (London: Verso, 2007), 69.

↩van Zanden, J.L., “Before the Great Divergence: The Modernity of China at the Onset of the Industrial Revolution,” Jan 26, 2011; Pomeranz, Kenneth,The Great Divergence: Europe, China, and the Making of the Modern World Economy (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2000).

↩Keynes, J.M., “The Economic Principles of Confucius and his School,” by Chen Huan-chang, The Economic Journal 22:88, December (1912) : 585.

↩Keynes, 585-86.

↩Rosenthal, Jean-Laurent and Bin Wong, “Another Look at Credit Markets and Investment in China and Europe before the Industrial Revolution,” Yale University Economic History Workshop (2005), 14-18; Rosenthal, Jean-Laurent and Bin Wong, Before and Beyond Divergence: The Politics of Economic Change in China and Europe (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2011), ch. 5; Rawski, Evelyn and Thomas Rawski, “Economic Change around the Indian Ocean in the Very Long Run,” paper presented at the Harvard-Hitotsubashi-Warwick Conference, Venice, July 2008.

↩Weber, Max, The Religion of China (1915), trans. by Hans Gerth (New York: Free Press, 1965), 26, 103–104, 61-62; Ertman, Thomas, Birth of the Leviathan: Building States and Regimes in Medieval and Early Modern Europe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 74–87; Tilly, Charles, Coercion, Capital, and European States, AD 990–1992 (Oxford: Blackwell, 1992), ch. 3.

↩Wakeman, Frederic, Telling Chinese History: A Selection of Essays (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009), 27–35.

↩Frank.

↩Weber, Isabella, How China Escaped Shock Therapy: The Market Reform Debate (London and New York: Routledge, 2021), 24–5; Wu, Baosan, A Study of Guanzi Economic Thought (Beijing: Chinese Social Sciences Publisher, 1989).

↩Nolan, Peter, China at the Crossroads (Cambridge: Polity, 2005), ch. 3; Weber, Isabella

↩Volumes 24 and 91 respectively, of the Book of Han, by Ban Gu (32-92 AD).

↩Sima, Qian, Records of the Grand Historian: Qin Dynasty, trans by Burton Watson (New York: Columbia University Press, 1995), 89–100; Ban, Gu, Food and Money in Ancient China: The Earliest Economic History of China to A.D. 25, trans by N.L. Swann, Nancy Lee (Princeton, 1950) (New York: Octagon Books, 1974).

↩Chinese Cooperation Times, “The First ‘Red’ Stock of Anyuan Railroad and Mine Workers’ Consumer Cooperative,” March 25, 2021; Hu, Deping, “In Response to the Question Concerning Supply and Marketing Cooperatives,” China Green Development Society, November 10, 2022, https://mbd.baidu.com/newspage/data/landingsuper?sShare=1&context=%7B%22nid%22%3A%22news_8738844951950484093%22,%22sourceFrom%22%3A%22bjh%22%7D.

↩Yu, Shude, “Lecture Notes on Cooperation at the First Training Class by the Chinese Disaster Relief and Charity Association,” 1925: http://www.coopunion.cn/news/zhuanjiaguandian/25bb209bcc4bc2160abc193f5a277db4.html; Yu, Shude, Lectures on Cooperation, (Nanjing: China Cooperation Study Society, 1934).

↩Hayford, Charles,To the People: James Yen and Village China (New York: Columbia University Press, 1990).; Lv, Xinyu, “Rural Reconstruction, the Nation-State. and China’s Modernity Problem: Reflections on Liang Shuming’s Rural Reconstruction Theory and Practice,” in Tian Yu Cao, et al. eds. Culture and Social Transformations in Reform Era China (London: Brill, 2010), 235-56.

↩Mao, “Why Is It That Red Political Power Can Exist in China?” October 5, 1928, Selected Works vol.1 (Beijing: People’s Publishing House, [1928] 1991); Mao, “A Single Spark Can Start a Prairie Fire,” 5 January 1930, Selected Works, vol.1,(Beijing: People’s Publishing House, [1930]1991).

↩Xiang, Guolan, “Red Finance,” Kunlunce Research Academy, October 3, 2021.

↩Kelly, Jason, Market Maoists: The Communist Origins of China’s Capitalist Ascent (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 2021), 26–29.

↩Kann, Eduard, “Paper Money in Modern China 1900-1956: Chinese Communists as Issuers of Notes,” Far Eastern Economic Review, Hong Kong (1957): part 25; O’Neill, E. F, “The Copper Cash and Silver Dollar Notes of the Hunan-Hubei-Jiangxi Workers’ and Peasants’ Bank,” in John Sandrock, The Money of Communist China (1927-1949) (Hong Kong: Shing Lee Company, 1989) part I; Sandrock, John (?), The Money of Communist China 1927-1949, part II: Money of the Base Areas during the War of Resistance against Japan 1936-1945.

↩Cao, Hong and Zhou Yan, “Mao Zemin: From a Peasant in Shaoshan to the Governor of State Bank,”Party History Review 6 (in Chinese) (2007); Xu, Shuxin, An Outline of the Development of Money in China’s Revolutionary Bases, (Beinging: China Financial Publishing House, 2008); Xiang, Guolan.

↩Wang, Zhongxin, “The Contemporary Relevance of ‘Salt Currency’ Created by Mao,” Kunlunce Research Academy, November 16, 2022.

↩Mao, “Fiscal Policy of the Border Region,”Collected Works of Mao, vol. 2, (Beijing: People’s Publishing House, [1938]1993).

↩Sandrock, part II.

↩Cui, Qimin, “An Analysis of the Guanghua Store’s Cash Coupons,” Modern Communication 17 (2019).

↩Li, Jinzheng, “Background: the Introduction and Revision of the Unified and Accumulated Tax Rules in the Shanxi-Chahar-Hebei Border Region During the Anti-Japanese War,” Studies of the Soviet Areas: 4 (2022).

↩Liu, Haibo, “An Analysis of the Revelation of Monetary Work in China’s Revolutionary Bases,” Global Finance no.6 (2013).

↩Zhu, Lizhi, Zhu Lizhi on Financial Governance, (Beijing: The CCP History Publisher, 2017).

↩Liu, Mohan, “Fiscal Wisdom of 土八路,” Huarun Magazine 7 (2022): 258.

↩Weber, Isabella.

↩Xue, Muqiao, “The Battle of Currency in the Shandong Base Area,” in Selected Economic Essays, Ch.6, Beijing: Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, et al (1984): 64–71.

↩Xue, Muqiao (1996), Memoirs. Tianjin: Tianjin People’s Publishing House.

↩Mao “Fiscal Policy of the Border Region.”

↩Xue, 65–67.

↩Weber, Isabella, 84, 102–03.

↩Weber, Isabella, 80.

↩Xue, 67.

↩Xue, 70–71.

↩Yu and Zhang.

↩Zhu, 5, 44.

↩Yu, 9.

↩

Filed Under