Richard Nephew, advisor to both the Obama and Biden administrations, candidly observed in his 2017 book that the outcome of sanctions depends on two factors: pain and resolve. The pain must be applied precisely and for maximum impact. Should the pressure point be missed or the injury blundered, sanctions may backfire, producing the perverse effect of merely steeling the target’s resolve.

The sanctions applied against Russia in response to its invasion of Ukraine signal a new era of economic coercion. Modern sanctions have typically been aimed at states on the periphery of the international order. By contrast, these have been issued against the world’s eleventh largest economy. In addition, Russia is a pivotal exporter of numerous vital commodities, a member of the Group of 20, and a permanent fixture on the UN Security Council. When the sanctions were issued, neither the aims nor the conditions for eventually revoking them were defined. Policymakers have spoken of requiring some Russian military retreat to end sanctions, but whether that means to positions as of February 2022 or January 2014 is unclear. In vaguer terms still, others have spoken of preventing Russia’s “destabilization of Ukraine” more broadly.

Pain

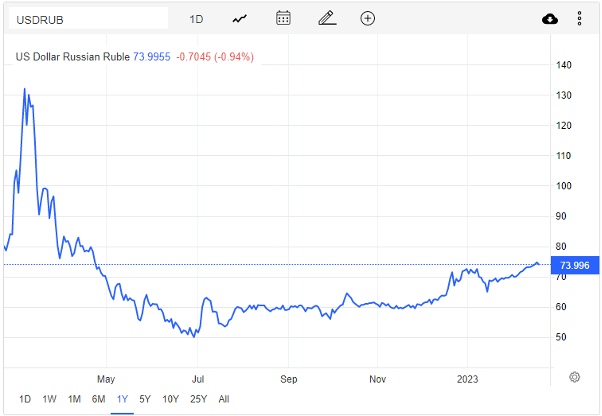

The pain administered thus far has been largely absorbed by its target. Contrary to the claims of the Biden administration, the sanctions against Russia are not “devastating their economy,” nor are they “crippling Putin’s ability to wage war,” as per the bombast of the UK government. The sanctions did not precipitate an immediate financial crisis, nor did the rouble collapse. Rather, the introduction of capital controls and restrictions on foreign exchange have stabilized the currency at its pre-invasion level.

Despite the initial 2.2 percent hit to its GDP in 2022, the International Monetary Fund has now upgraded its outlook for Russia’s 2023 output, predicting an expansion of 0.3 percent this year and 2.1 percent in 2024, putting the country ahead of both Germany and the UK. Even the sanctions most likely to impact the Russian war machine, such as the restrictions on the semiconductors needed for the more advanced sections of Russia’s armory, have been alleviated by a mixture of purchases from the private sector, a transition away from western suppliers, and routing imports via intermediaries located within the Eurasian Economic Union.

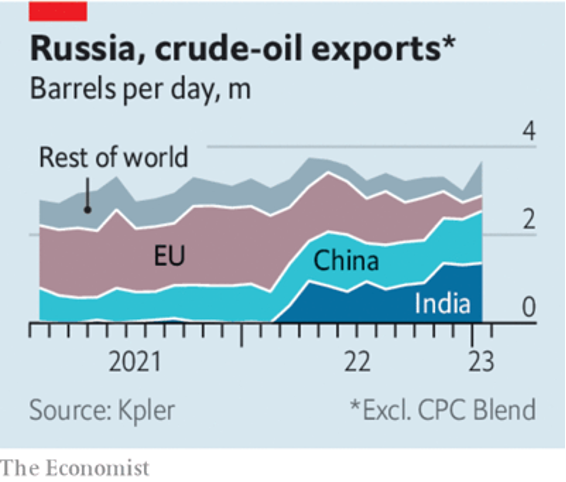

Future historians will question the western coalition’s priorities. It took just four days from the invasion to freeze the Central Bank of Russia’s foreign exchange reserves, but more than eleven months to finalize two long-discussed price caps on Russian oil exports, with the G7 cap on oil-based products now beginning to have a further effect on the cap on Russian crude in December. Measures targeting the financial system had limited impact as Russia has been able to fall back on its vast trade surplus, the fourth largest in the world. The oil price caps are designed to cut into that surplus, but they have come late enough that Russia has been able to construct a “shadow fleet” of tankers and a sprawling network of intermediaries to help blunt the impact.

The sanctions will do long-term damage to the Russian economy’s ability to innovate, particularly through the disruption of technology transfer networks and the loss of western business expertise in complex energy projects such as the efforts to increase oil extraction in East Siberia. Going forward, the trade restrictions will also exacerbate the continued failure of the Russian armed forces to modernize. The war, however, is being fought in the present.

Resolve

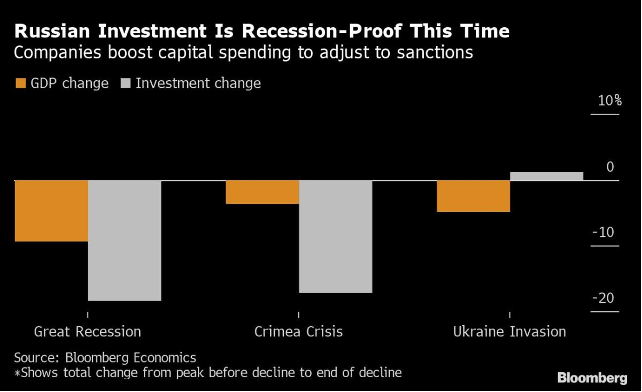

Sanctions, Nephew notes, must hit a moving target. The larger that target the greater the resources it has to mitigate the effects. The basis of Russian resolve lay first in the astute reaction of its economic technocrats—Elvira Nabiullina’s decision to stay at the helm of the central bank brought much needed continuity and pragmatism to the stabilization effort, as ultra-hawkish monetary policy smothered the risk of runaway inflation. With the worst fears averted, Russian political economy shifted toward what political scientist Volodymyr Ishchenko has called “military Keynesianism.” This involved offering generous wages for conscripts and volunteer soldiers, building a vast public works program aimed at the reconstruction of newly annexed regions of southeastern Ukraine, and enlarging an already sprawling military-industrial complex. Expenditures are likely greater than 5 percent of GDP already.

As their western competitors recede in the domestic sphere, Russia’s national capitalists are consolidating, reflecting the nuanced and uneven real life consequences of sanctions often belied by the triumphant rhetoric that accompanies them. National business investment has been revitalized as companies reorient supply chains and substitute imports of foreign goods and technologies. Customers are still ordering burgers from the same staff in the same buildings that once housed McDonald’s, but the revenues now flow to Siberian billionaire Alexander Govor and his network of franchises, which operate under the name Vkusno i tochka (“Tasty and that’s it”).

Meanwhile, the Russian state has moved aggressively to circumvent sanctions. These are not merely short-term work-arounds, but rather lasting shifts in the economic geography of Eurasia. To take just one example, Russia and Iran are together spending up to $25 billion to create a 3,000 kilometer trade route stretching from Europe to the Indian Ocean, vastly shortcutting existing routes between the two countries. This project includes a $1 billion canal expansion project connecting the Volga River to the Sea of Azov, making inland waterways navigable year-round and easing congestion between the Black and Caspian Seas. The head of Russia’s Chamber of Commerce now talks of a “clear path” to Russia-Iran trade reaching $40 billion annually, up from $5 billion, and is pushing for a comprehensive free trade agreement to follow the recent $40 billion joint energy exploration deal between the National Iranian Oil Company and Russia’s Gazprom.

This rerouting of physical trade routes has been accompanied by wider shifts in the composition of global trade. India and China have stepped in to buy hydrocarbons at a discount that would once have been bound for Europe, ensuring that commodity revenues continue to flow to the Kremlin. While much has been made of the changing destinations of Urals crude, less has been said about other energy exports such as fuel oil. Commodity analysts estimate that China accepted a record 5.62 million barrels of Russian fuel oil in February, with India having purchased 4.5 million barrels the month before, three times its 2021 average purchase. The United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia have also drastically increased their purchases of Russian fuel oil to 3 million and nearly 2 million barrels per month, respectively, utilizing the cheap imports to power their energy system and preserve more domestically-produced crude for export.

Importantly, these new heavyweight purchases of Russian fossil fuels are increasingly being made in renminbi, rupees, and dirhams instead of the dollars that previously gave the US—through the Federal Reserve and the omnipresent Office of Foreign Assets Control—a lever to apply sanctions pressure. China now makes purchases from Gazprom half in roubles and half in renminbi, and President Xi Jinping used a speech in December to ask Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries to use the Shanghai Petroleum and National Gas Exchange as a platform to carry out yuan settlement of oil and gas transactions.

Still, there will be no overnight de-dollarization of the international energy market. Bilateral trade flows between China, Russia and the GCC currently account for just 2 percent of global trade, but the essential components for what the recent meeting of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization called “the gradual increase in the share of national currencies in mutual settlements” are now in place.

Sanctions scholars have long posited the concept of a “black knight”: a “powerful or wealthy ally” of a target country whose “support can largely offset whatever deprivation results from sanctions themselves,” as Gary C. Hufbauer put it. Russia has not one black knight but several—a cavalry of the willing, driven less by chivalry than by a potent combination of mutual fear and material benefit.

Loyalty

In the face of Russian resolve, a growing consensus of experts have concluded that “peak” sanctions have probably passed. As Agathe Demarais put it, “American diplomats will be soon deprived of their favorite weapon to cajole, threaten, or punish US enemies.”

The hazard in this argument is that it underestimates the scale of the shift in the nature and purpose of sanctions that is currently underway. Western sanctions against Russia are not intended to “succeed” in the conventional sense, which is to persuade a target to reverse course on a contentious policy issue. They are better seen as a vehicle for demarcating economic territory, reorientating the map of western capitalism away from a regional hegemon now viewed as irredeemably unreliable. This is also the logic behind the US sanctions on China’s advanced technology sector, for which Washington is currently requesting support in European capitals, seeking to embed “strategic competition” for the long term. Such measures inevitably incur escalating responses from their targets, such as so-called “blocking statutes,” legislation increasingly favored in both Russia and China that makes complying with foreign sanctions illegal, thereby forcing multinational companies to choose sides.

Sanctions thus serve an important purpose for powerful factions within both capital and government, particularly national security establishments that have long fought internal battles against advocates of free trade and cosmopolitan economic integration. In this demarcation of the economic landscape, a highly volatile international order is emerging, characterized by slowly decoupling supply chains, weaponized interdependence, and perpetual low-grade financial conflict.

In 1970, Albert Hirschman described the options available to those witnessing a decaying status quo in the dichotomous terms of either “exit” or “voice.” The choice between them, he said, was dictated by loyalty. As international trade begins, in Olaf Scholz’s cautionary words, to “separate into competing blocs,” the global battle for that loyalty is heating up.

In an attempt to prevent the growing international voice against US economic dominance from escalating into a call for exit, Secretary of State Antony Blinken and Secretary of the Treasury Janet Yellen began 2023 by conducting a “listening tour” through Kenya, Nigeria, Senegal, Zambia, and South Africa. They urged compliance with US sanctions and emphasized both Russia’s blame for rising global food prices and China’s role as a barrier to debt relief for African countries. Meanwhile, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov met with officials in Angola, Eswatini and Eritrea, pushing Russia’s trademark counter-offer of arms, advisors, and energy to an increasingly receptive audience.

But the world will not fold neatly into self-sufficient trade blocs led from Beijing, Washington, or Moscow. Although two-thirds of the global population live in countries that have not explicitly joined the sanctions regime against Russia, many financial institutions within those countries have attempted to strike a balancing act for fear of losing access to crucial dollar markets. This creates a quiet bifurcation, as leaders talk tough on US domination while their banks quietly submit to it. Turkey’s two largest lenders recently halted the use of Russia’s SWIFT alternative, Mir, following new guidance from the US Department of the Treasury, and even financial institutions in China and Hong Kong have mostly fallen into line. Elsewhere however, despite a tentative deal involving the Netherlands and Japan, the US appears to recognize it cannot bind the EU as a whole to its export controls against China. In wooing the undecided, Washington will continue to oscillate between promising constructive assistance and threatening to reimpose secondary sanctions.

Despite the deficiency in short-term pain inflicted against Russia and the resolve that has been precipitated, sanctions appear set to proliferate yet further—“dead but dominant” in the formulation of Jürgen Habermas. With all eyes on the US and China, less noticed is the increasing willingness with which the other power centers of the multipolar order—from Riyadh to Tokyo—have also weaponized trade in pursuit of political goals. This geoeconomic patchwork of state-led coercion, fragile alliances, and frequent countermeasures necessitates a more complex understanding of the role of sanctions, one that involves going beyond traditional determinants of success and instead asking of a given measure, like Cicero, “Cui bono?”

Filed Under