Watch the Korean Peninsula. It is in South Korea that the New Cold War has most visibly upset the delicate balance between industry, security, and domestic politics.

South Korea’s growth miracle has been based on deterrence and detente between China, its main trading partner; the United States, its ally and security guarantor; and North Korea, its neighbor with newly developed intercontinental ballistic missiles. The country has been on hair-trigger alert since last October, when North Korea stepped up its barrage of ballistic missile tests, including launching one over Japan. In a show of strength, South Korea launched its own ballistic missile, but the weapon malfunctioned, crashing in the coastal city of Gangneung, where the resulting fire raised panic of a North Korean attack.

Now that North Korea has demonstrated the ability to strike the US homeland, South Koreans worry that Washington might abandon them in a conflict to protect US cities instead. Today, 71 percent favor developing their own nuclear weapons. “New York for Berlin” was the central extended deterrence dilemma of the old cold war. The new question is: Would the Americans really trade “Seattle for Seoul?”

Last week, while the national security advisor Jake Sullivan was unrolling the “new Washington consensus” (the subject of our next dispatch), Presidents Biden and Yoon were holding security and trade negotiations in DC that resulted in a Washington Declaration. “Our mutual defense treaty is ironclad, and that includes our commitment to extended deterrence,” Biden said, referring to the treaty signed to end the Korean War seventy years ago. For his part, Yoon referred to the “unprecedented expansion and strengthening” of the US nuclear umbrella. The upshot was that South Korea agreed not to pursue its own nuclear weapons program in return for a greater decision-making role in US military planning should North Korea launch a nuclear attack.

The interwoven region

The new Cold War has upset forty-four years of peace in the world’s region of fastest economic growth and development. In 2000, the Asia Pacific was responsible for just over a quarter of global GDP; now that figure is well over a third, and projections abound for it to exceed half in the next two decades.

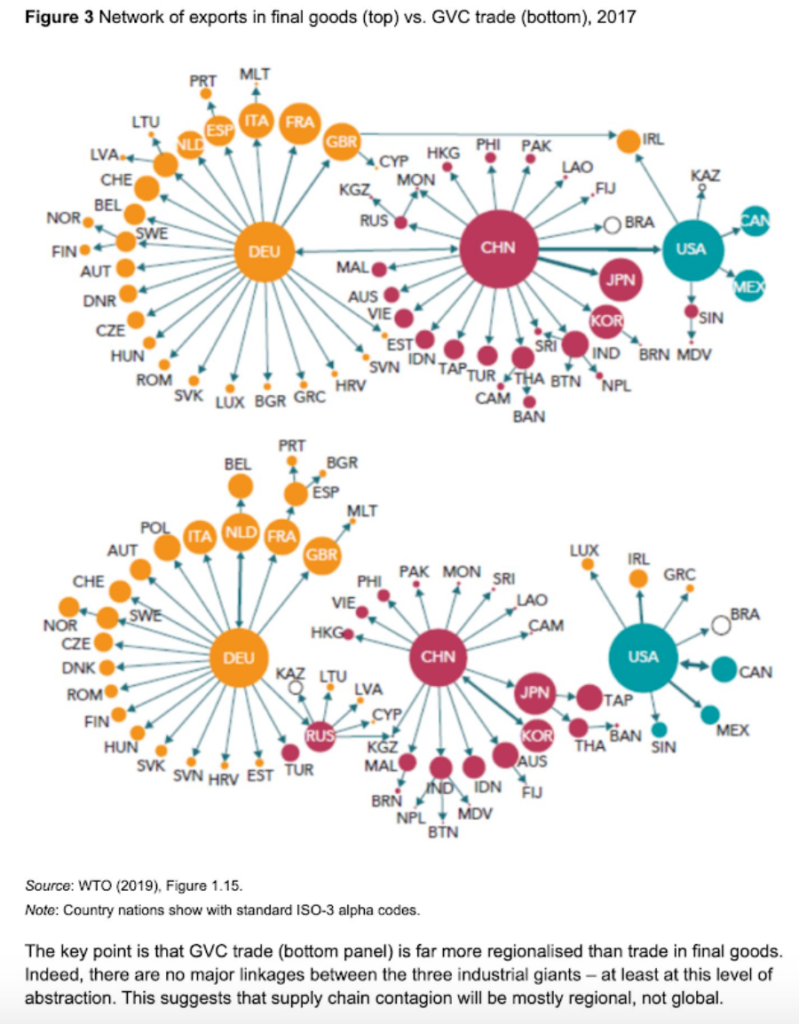

The region is also adversely affected by Washington’s bans on third parties selling to China technologies deemed relevant to national security. Jake Sullivan’s phrase “high fence, small yard” evokes surgical precision, but Asian supply chains and economies are so interconnected that bans and ensuing retaliations will be far messier than the view from Washington suggests.

East and South East Asian economies especially are tightly woven together by transborder just-in-time supply relationships. Firms have export markets not just in Europe and the Americas, but also within Asia’s large consumer market. This economic interdependence means that any disruption to critical industries—chips, cars, batteries, biotech—ripples across the region.

The regional connections are increasingly formalized, too. In 2020, the ASEAN countries, as well as China, Japan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand signed the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership. Although it didn’t include tariff reductions, some observers saw the new partnership as representing progress towards a China-Japan-Korea trade agreement, or even a regional trading zone. The divide between restrictionist national security hawks and cooperationist economic liberals that we wrote about last month holds in Asia. During a trilateral ministerial meeting last week, South Korea’s Finance Minister Choo Kyung-ho stated that “China, South Korea, Japan cooperation can be the new engine for global growth.”

In an effort to counter a more assertive China, Biden launched a new trade initiative with twelve countries. But the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework has been criticized by Asian countries for failing to provide greater access to US markets.

North Korean deterrence

This year, South Korea increased its military spending by 4.3 percent and upgraded its US-operated THAAD air defense system. Korean officials have held discussions with the Pentagon about Taiwan-related contingencies. Still, Seoul’s overwhelming focus remains on North Korea and not Taiwan. The worry that in the event of war in Taiwan, the US could pull some of its 30,000 armed forces out of Korea, leaving Seoul to deter Pyongyang on its own.

Since 2017, politicians in Japan, South Korea, Australia, and India have taken a harder line against Beijing. For the most part, they have the backing of public opinion in this. The heightened military posture and cycle of tit for tat responses threatens to kill the detente goose that laid the golden egg of the Asian growth miracle.

The US is now demanding that its allies cut off Chinese markets and reorganize their supply chains. Last October, Washington announced export controls on certain semiconductor sales to China, which cannot work without cooperation of the Dutch and Japanese, whose companies produce the lithography equipment used for making chips. That support was won, somehow. In another example, citing national security, Beijing has threatened a domestic ban on Micron, a US microchip firm that received big subsidies under the CHIPS Act. The White House reportedly wanted the South Korean government to urge Micron competitors Samsung and SK Hynix to not rush to increase their market share in China at Micron’s expense, should the ban take effect—which it ultimately did not.

Labor at home

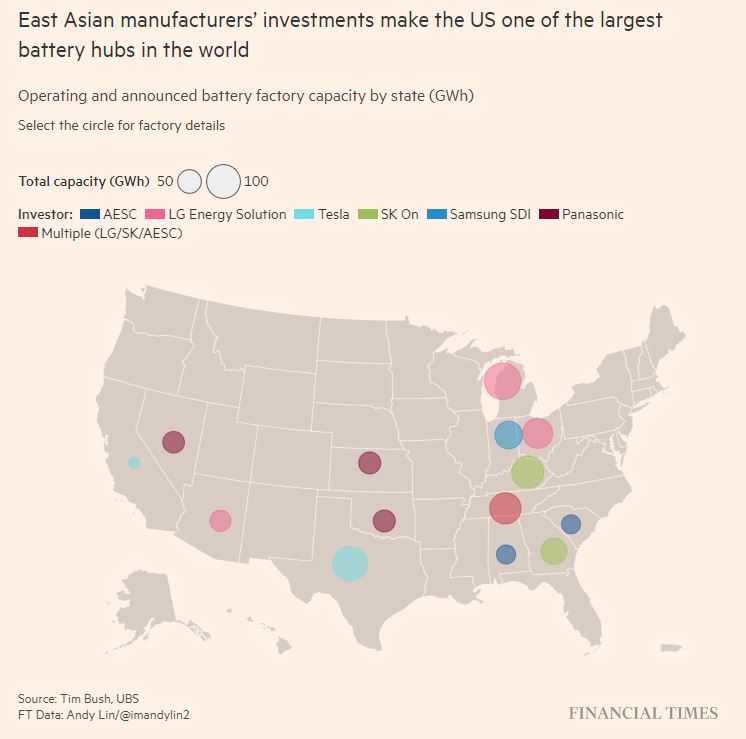

Against this geopolitical backdrop, domestic conflicts continue to plague US politics. Not a single Republican voted for the Inflation Reduction Act. Rustbelt protectionists and progressives agree that free trade agreements have been bad for American workers. The new “buy American” and “made in America” provisions, which are intended to win back votes in the rustbelt, are policy instruments designed to create jobs at home, not abroad. It’s a policy that conflicts with the top national security priority to do whatever it takes to bring American allies into an anti-China coalition. Countries like Japan and Korea want to maintain non-discriminatory access to the vast US market, without too many strings attached. That market access is precisely what rustbelt senators, who favor domestic content requirements, wish to deny.

Meanwhile, East Asian (and EU) countries are opposed to “high road” labor standards that would make sure that companies receiving subsidies give workers high wages and continue to invest in non-union states in America. While South Korea’s Hyundai and Kia have dramatically expanded in the US, they won’t be eligible for IRA tax credits for another few years, until their plants start producing vehicles, because their EVs contain batteries made in China. The US administration is stitching a patchwork of bespoke bilateral agreements in a bid to satisfy competing domestic political economy and security interests. In March, it signed a critical minerals trade agreement with Japan to enable Japanese cars to qualify for IRA subsidies, which had “toothless provisions on labor and environment,” as Mireya Solis, at Brookings East Asia pointed out. For their part, Japanese firms are apparently worried about the trade-offs of relinquishing big Chinese markets.

These new White House agreements bypass Congress ratification. Asian countries worried that such deals will be reneged if the GOP comes into power will want to hedge against such risks and minimize trade-offs with Chinese markets. Indonesian industry groups have floated a “Chinese and a non-Chinese portfolio” for domestically-produced batteries that use local nickel. Such fragmented supply chains will likely become common features of global trade and industry.

South Korea remains on edge with threats of Chinese economic retaliation to the Washington Declaration. China could also resort to hard power coercion. The peace that knit together the growth miracle for over three billion people could end in a bang and not a whimper. G7 countries negotiating the new Washington consensus in mid-May go, fittingly enough, to Hiroshima.

Filed Under