We are quietly witnessing the largest shift to austerity undertaken in this century. Debt-strained developing countries are making further cuts to already ragged budgets, in many cases as they battle to meet punishing new conditions demanded by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which held its Spring Meetings last week in Washington DC.

Yet this trend was easily missed at the so-called Springs, where discussions of stalled talks on debt restructuring drew most headlines. That is partly because the Fund’s push towards “fiscal consolidation” comes despite, and not because of, the Fund’s stated ideological commitments.

In its World Economic Outlook, the IMF readily admits that austerity is—on average—unhelpful. Economic growth is a better engine for shrinking debt burdens. But given the grim growth outlook, the IMF has another prescription: do austerity again, just do it better this time. Despite acknowledging that fiscal consolidation—its main recommendation—“tends to slow GDP growth,” the IMF is encouraging countries to stick with it. Why? Because in the IMF’s view, stabilizing inflation should take precedence over growth. That is, fiscal policy must be tight and work in tandem with tight monetary policy.

Countries will go to great lengths to avoid going to the IMF, with its political and market stigma, and its imposition of structural adjustment. The last resort for distressed countries, the IMF charges a high price for its support; its policy prescriptions are onerous and politically challenging, a source of humiliation among domestic constituents and international relations alike.

To understand why, consider the IMF’s role and function. The institution is called in when countries have balance of payment crises and are unable to make debt repayments, or buy food and energy. In return for its last-resort liquidity, countries must adhere to a policy program that the IMF deems will put their accounts on a more secure footing.

Countries pay their external debt obligations out of export earnings. Therefore, the IMF has usually prescribed programs to support hard-currency earning industries that are sold on a global market—fossil fuels, minerals, and industrial agriculture—or policies to attract foreign direct investment to boost services like technology and tourism that earn governments precious dollars. Countries that avoid IMF programs have successfully internalized that same logic, with their finance ministries enforcing the prioritization of hard currency buffers and constraining other spending ministries by cutting budgets for public employees, such as teachers and healthcare workers.

In 2013, with Greece suffering from 25 percent unemployment and facing a decades-long struggle to regain its pre-crisis GDP, IMF staff acknowledged that they had underestimated the fiscal multiplier in devising Greece’s program. They had thus failed to anticipate how severely the economy would contract after implementing the harsh cutbacks required by the IMF-ECB-EU troika bailout.

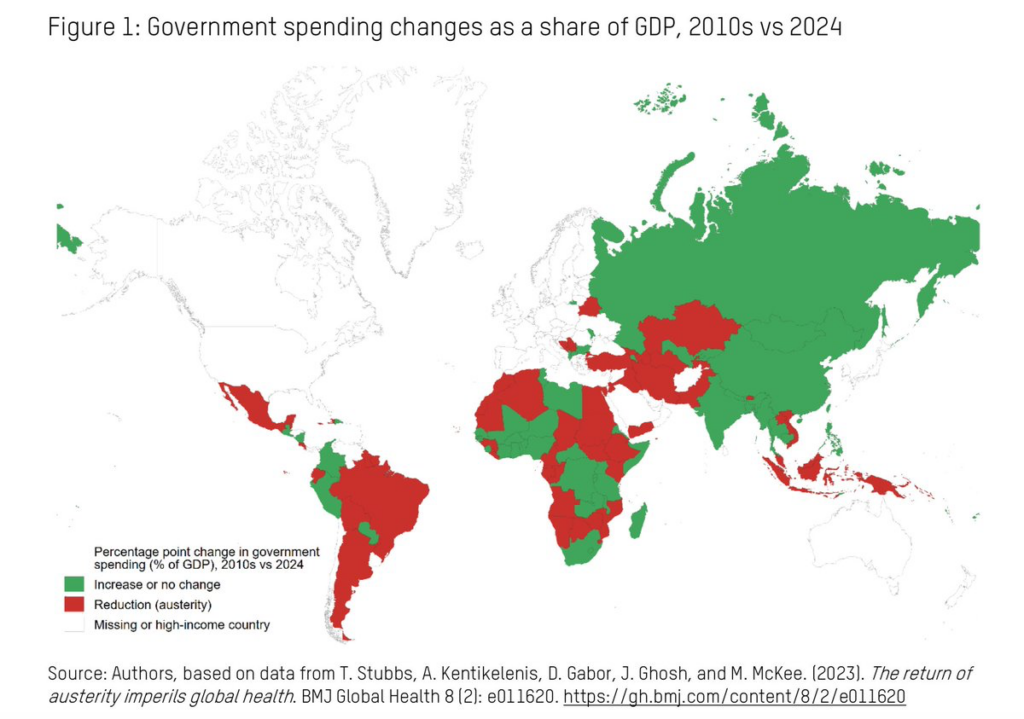

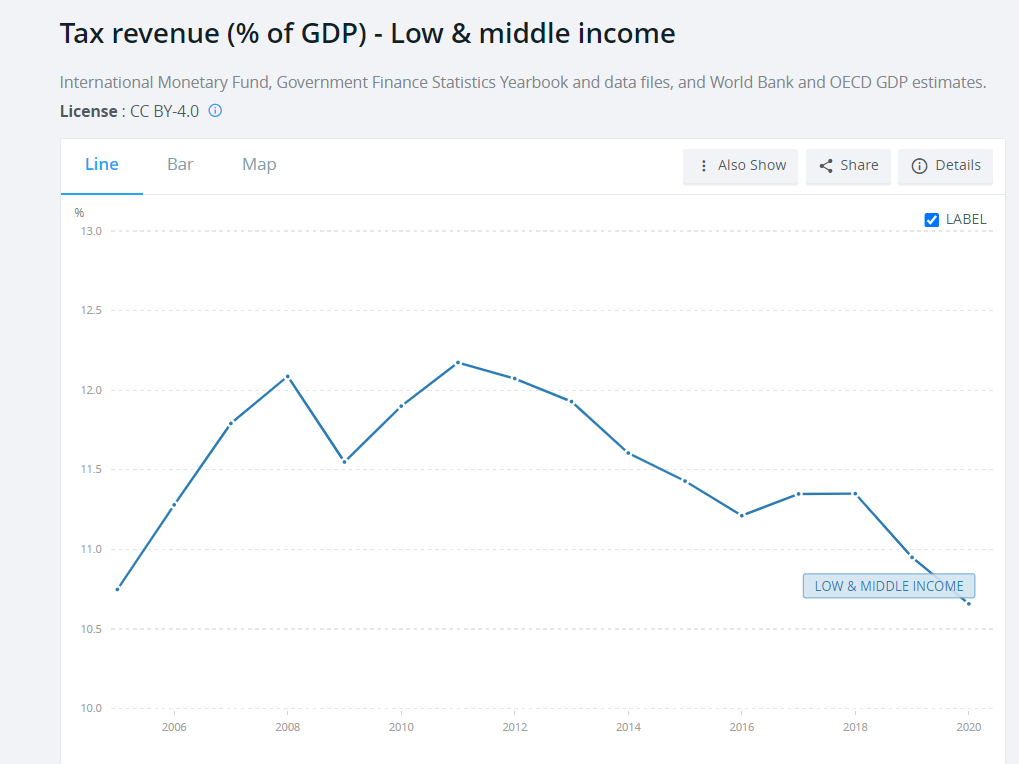

Since the pandemic began in 2020, the IMF has provided nearly $300 billion in financing to ninety-six countries, in many cases via rapid response facilities. By mid-2021, ninety-one of the 107 Covid-19 IMF loans either recommended or required countries to adopt austerity as a policy. By 2024, Oxfam researchers found that, “Fifty-nine out of 125 low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) are expected to spend less than during the 2010s, exposing a total of 2 billion people to the harmful consequences of budget cuts.”

Oxfam researchers also looked at the “unconditional” lending to the seventeen countries in traditional IMF programs in 2020 and 2021, and found that they were unsurprisingly, not unconditional. What was promised as emergency lending has now turned into a gigantic austerity drive.

The austerity that the IMF peddled in the 2010s devastated 600 million people in the North Atlantic. Over 6 billion people now live in the grip of austerity across all country income categories, according to an analysis by economists Isabel Ortiz and Matthew Cummins.

They identified government austerity policies such as targeting social protection (in 120 countries); cutting or capping the public-sector wage bill (in ninety-one countries); privatizing public services/reform of State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs) (in seventy-nine countries); pension reforms (in seventy-four countries); labor flexibilization reforms (in sixty countries); and cutting health expenditures (in sixteen countries). Many of those people live in countries outside of IMF lending programs or any program at all—but the Fund’s influence extends to those countries through signaling via its own pronouncements, precautionary programs and country monitoring.

Austerity does not cut debt-to-GDP ratios or help meet climate goals. It is costly and deadly. Slashing government spending reduces GDP which makes debt servicing yet more difficult. Crucially, austerity makes countries more fragile and less resilient to future shocks. When public health workers or firefighters lose their jobs now, who will put out the fires later?

Austerity can also trigger recessions that lay waste to lives. Recessions result in “sizable and highly significant increase in mortality,” found researchers at the Bank of International Settlements. That recession-mortality relationship is strongest in emerging and developing countries who suffer an extra 3.4 deaths per 1000 people during a recession. The devastating effects of 2010s austerity are now plain to see in the rich world, with falling life expectancy in the US and UK. The number of lives lost in developing countries from a world recession could be in the millions.

Last year’s IMF Fiscal Monitor, titled “Helping People Bounce Back,” aspired to a world in which governments are able “to ensure everyone has access to affordable food and to protect low-income households from rising inflation.” Of course, it added, this should not be accomplished through price controls, subsidies, or tax cuts, which would “be costly to the budget and ultimately ineffective.”

The Fund instead has prescribed, as standard since 2019, that the poorest should be protected during fiscal consolidation by implementing “social spending floors” that ringfence critical government spending areas like health and education.

Oxfam’s researchers analyzed all seventeen low- and middle-income countries that entered IMF programs in 2020-21, and found that social spending floors were nothing but a “fig leaf for austerity”. Most damningly, they find “for every dollar that the IMF provides to a poor country for social spending, it requires the country to cut four times more through austerity measures.”

Austerity holds back a big green investment push

The IMF has been clear that it sees climate as “macro critical” and hence can be included in its mandate to preserve financial stability. Again, though, its actions on the ground have remained stuck in the past.

Building emission-free generation and demand infrastructure will require capital, as much in developing countries as advanced economies. A report published in November by Vera Songwe of UNECA and Nick Stern of the LSE confirmed that roughly $2 trillion per year is needed for developing countries to meet climate goals. As recently as 2020, the IMF viewed decarbonization purely as a cost but an analysis it published in October that year found that net zero by 2050 would be positive for growth.

In its climate-related analysis and advice, the IMF still strongly pushes for carbon pricing as the central climate policy instrument. It does this even as western governments in high-income countries embrace “big push” investment approaches, and while research concludes that carbon pricing is insufficient (without accompanying regulation and investment) and politically unpopular.

As noted by an independent taskforce reviewing the IMF’s policies, convened at Boston University’s Global Development Policy Center, “the pursuit of net-zero pathways is expected to lead to high levels of public debt.”

Taxes are an alternative to austerity

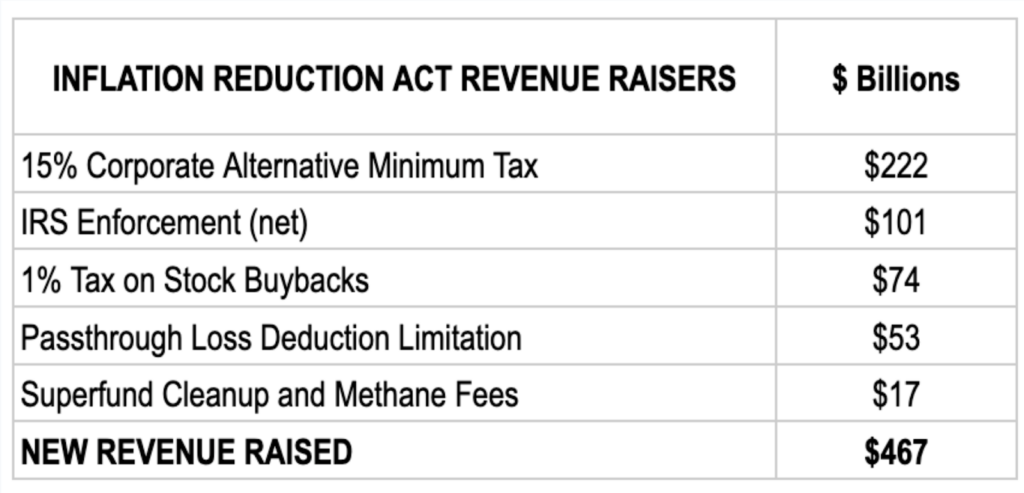

With tight public finances and corporate treasuries fattened on profits, governments should focus on raising revenues through taxation rather than cutting budgets. Though it has gone entirely unmentioned, the US Inflation Reduction Act is a tax bill: climate and healthcare spending is funded by taxing the rich. The IRA imposes a 15 percent corporate minimum tax and gives the IRS $80 billion in resources to go after tax dodgers. The US Treasury estimates that every dollar of tax-enforcement resources given to the IRS raises four dollars in revenue. The IRA also raises $74 billion in revenue by imposing a 1 percent financial transactions tax on stock buybacks.

Similar policies are being raised in national parliaments around the world. In Argentina, a wealth tax on the wealthiest residents raises almost 0.5 percent of the country’s GDP ($2.4 billion), while Colombia’s left-wing government is undertaking a progressive taxation overhaul. Encouragingly, countries as varied as Italy, Mozambique, UK, and Bolivia have taxed windfall profits of energy companies to fund social services.

Filed Under