Behind the retail grocery industry’s image of public routine churns an incredible and evolving feat of collective enterprise. The companies that own and operate grocery stores serve as the primary source of food for the country’s 130 million households. Employing some 2.8 million workers across 62,000 locations—about three stores for every incorporated municipality in the country—supermarkets are anchor institutions in the developmental pattern of American capitalism. (Employment at warehouse clubs such as Costco and supercenters such as Walmart: another 2.4 million workers.)

Supermarkets have also undergone a phase of restructuring. Over the past generation, as general merchandise retailers such as Walmart or Target have used their distribution networks to move into food, supermarket owners have responded by consolidating ownership. Stitching together larger and larger purchasing networks through waves of mergers, the modern grocer has become a species of the broader family of retail giant, pulling the commodities of the erstwhile truck farm and wholesaler of manufactured foods through the new “logistics” industry that has grown up since the deregulation of trucking and airlines in the late 1970s.1

Today, over half of all sales in food retail come from just eight companies.2 The two largest grocery-store owners, Kroger and Albertsons, together employ one in four retail grocery workers. In October 2022, these two industry leaders reached a merger agreement: Kroger would purchase a 100 percent equity stake in Albertsons for $24.6 billion. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) opened an investigation, subpoenaing over 2 million documents from Kroger and Albersons and an additional 300,000 documents from ninety-one third parties. In an attempt to persuade the FTC to allow the merger, Kroger entered into an agreement with third-party C&S to sell 413 stores—a technique Albertsons used to complete the purchase of Safeway in 2015 (it later purchased the third party in that deal.) Unsatisfied with this remedy, the FTC’s general counsel on February 26, 2024 filed a complaint in the United States District Court for Oregon seeking a preliminary injunction pending findings by the FTC.

The FTC’s complaint identifies over 100 metropolitan areas in seventeen different states where Kroger and Albertsons subsidiaries currently compete in the same geographic markets for customers, labor, and suppliers. In these places, it argues, a combined Kroger-Albertsons could raise grocery prices and lower grocery wages. Nine state attorneys general joined the complaint seeking a preliminary injunction. Under the original terms of the deal, Kroger and Albertsons have until October 9, 2024 to complete the transaction, after which either party may exit.3

Kroger and Albertsons have sought to delay both the Oregon hearing for a preliminary injunction and the Washington hearings of the FTC. The companies have yet to say whether they will extend the deadline of their merger agreement until after October 9 in the event an injunction is granted in any court. Hanging over all of this is, of course, the federal election on November 5. Historically, when antitrust legislation is enforced and tight elections approach, large mergers proposing to reorganize ownership of entire industries turn on partisan control of the White House. Nixon approved the Pennsylvania Railroad’s purchase of the New York Central in 1969 after Johnson had delayed it, and Nixon offered antitrust relief to ITT in exchange for funds for the 1972 Republican National Convention. A veritable merger wave, the century’s third, followed corporate America’s shift to Reagan in 1980. In October 2016, when many expected a Clinton victory, AT&T announced its plan to purchase Time Warner. Recently Trump has said explicitly to the oil industry he will allow consolidation in his next administration.

To understand how the industry’s evolution brought the merger and public challenge from the FTC and the states, Phenomenal World editor Andrew Elrod spoke with John Marshall about the history and economics of the US retail grocery industry. Marshall is director of capital strategies for UFCW Local 3000, which represents over 52,000 grocery workers in the Pacific Northwest; advisor to the president for UFCW Local 324, which represents over 22,000 grocery workers in California; and is also a former senior capital markets economist for the UFCW International Union.

andrew elrod: Just this past December, the US Census released its most recent data on the number of firms, establishments, employment, and payroll in the US economy. It found over 96,000 grocery store locations employing nearly 3 million workers.

Three quarters of employment came from less than 1 percent of companies, which own a quarter of all locations.4 So employment is dominated by larger stores. There were also 20,000 specialty food stores and 53,000 general retailer or “big box” stores. Altogether, these 170,000-some establishments are the main points of distribution of household food in the United States. With average household spending around $8,000 per year, the 130 million households in the US make this a trillion dollar market.5 It’s also a market critically important to public welfare: in the US, earners in the bottom half spend between 9 and 40 percent of their after-tax earnings on food at home.

How does this rough description compare with your understanding of the industry? What do these census statistics leave out or obscure in the structure of the retail grocery market?

John marshall: Those figures are basically consistent with my understanding of the industry. Food is bought and sold everywhere from farmers markets to convenience stores to airport lounges, from restaurants to traditional grocery stores, and so on. Government agencies and private sector research institutions employ different parameters, but the figure that people generally use when they talk about the grocery industry is something between $900 billion and a trillion, and as you said, if you’re going to be even more expansive, up to one and a half trillion—that’s if you include the soda sold at the drugstore. In the traditional “one-stop-shop” grocery store segment of the market, Kroger and Albertsons are the two leaders.

There is segmentation of the industry across the various supermarket brands in the United States, corresponding to the changes in distribution of income in the workforce. Forty years ago, we were a less unequal society, and middle-income grocers like Kroger and Safeway had a larger market share because the middle class was larger. These were middle class grocery stores that offered middle class products to families with middle class desires and tastes.

What we’ve seen now is the hourglass-ing of the supermarket industry: significant growth at the high end targeted to higher income consumers, like Trader Joe’s, Whole Foods, and Sprouts, which have premium natural organic products, and warehouse clubs like Costco, which also have a significantly higher household income customer base.

At the same time, there’s been significant growth at the low end: Walmart, Dollar Tree, Dollar General, Family Dollar. Hard discounters like Aldi and Grocery Outlet have grown significantly as well. The changing nature of supermarkets and who they’re catering to has followed changes in income distribution pretty closely.

This is the larger backdrop but it’s important to point out that there’s no reason why Kroger and Albertsons couldn’t also be expanding their store footprints as well. Kroger has a discount banner—Food 4 Less—which is very profitable but they haven’t invested in expanding it. Instead Kroger and Albertsons have spent billions of dollars on Wall Street investor payouts.

ae: And now the two largest firms at this “middle of the market” position are trying to merge, and the Federal Trade Commission, led by administration appointee Lina Khan, is trying to stop this deal.

jm: The proposed Kroger-Albertsons merger is, I think, a significant turning point in the industry, and is symptomatic of some underlying trends.

The industry has been consolidating slowly but surely for decades. In the 1960s and 1970s, we had a very fragmented market with lots of relatively small operators in many local markets across the United States. That began to change with the introduction of scanner technology at the checkout in the 1980s and 1990s, when grocery stores began to consolidate significantly because you had to have capital and scale to invest in that technology. Local grocery stores or bodegas weren’t able to.

This consolidation happened at the same time as the increasing introduction of new products and services into supermarkets. So you began to see delis and meat counters, seafood counters, pharmacies, fuel centers, and floral departments—significant new product lines that had previously been the purview of specialized retailers were consolidated in what we now call supermarkets. The square footage of supermarkets grew significantly during this period, and employment grew in the sector as well.

ae: What have the trends been since this earlier wave of consolidation?

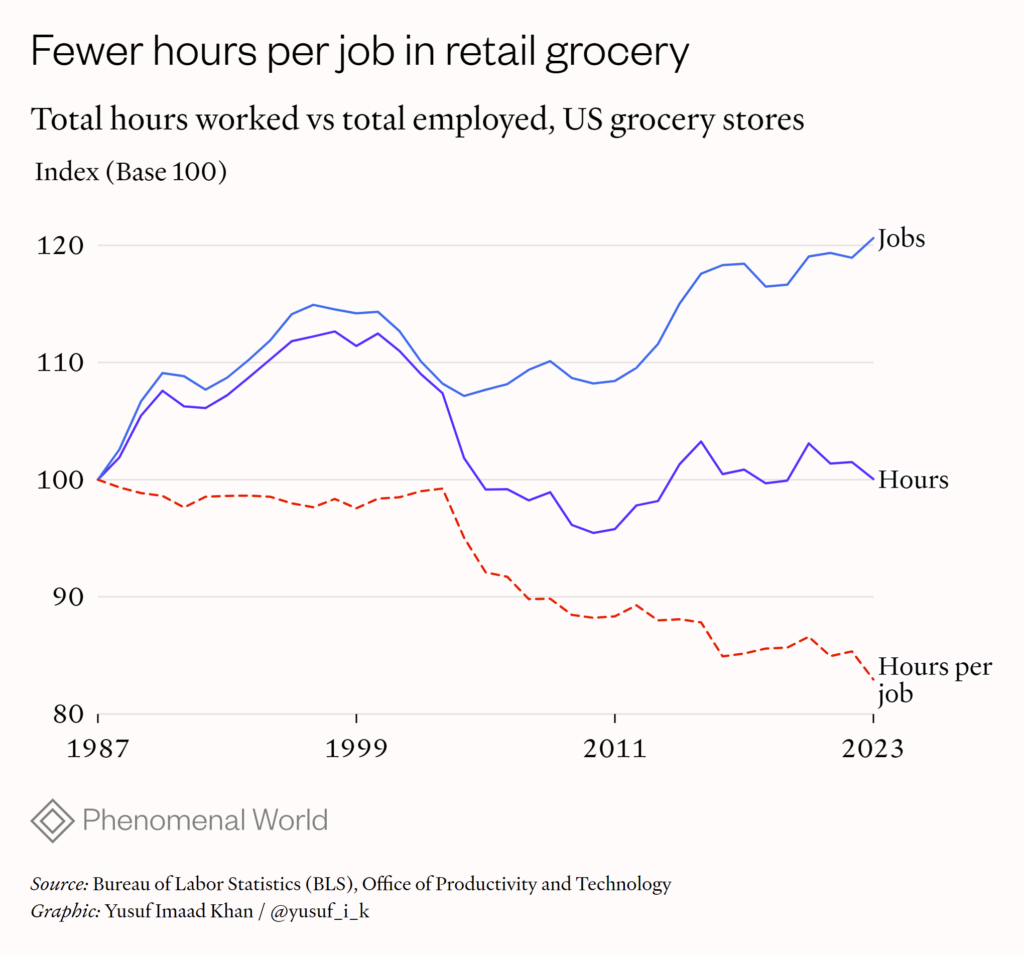

jm: If you go back to the early 1980s, according to the best data that’s available, about 35 percent of the industry was unionized. Today it’s about 13 percent. During the late 1990s—when the union firms were consolidating—we saw the peak in labor hours, the peak in employment in the sector, and a peak in average weekly compensation for workers.

Then in 2003 there was a major strike of over 70,000 UFCW members lasting over four months in Southern California against the major employers, including Kroger and Albertsons and others, such as Safeway, which is now part of Albertsons. I call it a strike but it was really a lockout deliberately instigated by the employers, with the intention of imposing a second, lower tier of employment—more part-time work, lower pay, less benefits, and so on. The union employers used the threat of Walmart as an excuse to justify cutting costs, although Walmart had a relatively small share of the Southern California market. And they succeeded. If you look at the aggregate data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, not only for union workers but for nonunion grocery workers as well, there’s a real turning point in 2003. Wages began to stagnate and, in real terms, decline. Hours declined, and hours per worker declined even more, from thirty-two hours per week down to about twenty-eight hours per week—where it remains today. This reduction in weekly hours is a critical element of the way the employers restructured work in the industry, because it keeps workers in a state of precarity—more easily manipulated by managers and more willing to accept undesirable shifts simply to get more hours. This essentially created an internal reserve army of labor.

This attack on labor standards was made possible by the merger wave of the 1990s that allowed the employers to become larger and more geographically expansive, and it gave them the financial ability to weather a long strike. That four-month strike was very damaging to both the union and to standards in the industry. One of the main lessons the UFCW took away from that defeat was that it was no longer possible for individual locals in one part of the country to negotiate in isolation from other locals, and that nationally coordinated bargaining with the major retailers was a necessity if we were going to survive. Unfortunately that lesson was quickly forgotten and only a handful of UFCW locals have coordinated in recent bargaining rounds. The group of locals I’m currently working with is trying to expand that coordination, and the merger fight has helped us build toward that goal.

The crucial context for the 2003 fight was the significant growth in competition from super centers, specifically Walmart, that had begun to introduce grocery products into their discount store formats. Previously, Walmart was just general merchandise, but in the 1990s and 2000s they ramped up their sale of grocery products. Of course, Walmart is famous for “everyday low prices,” and these employers in the union sector—Kroger, Safeway, Albertsons, and others—decided that they needed to significantly reduce labor costs in order to compete on price. To be clear, the union employers were not yet facing meaningful competition from Walmart in Southern California, but they used the threat of Walmart as one rationale for attacking labor.

Alongside Walmart, major retail employers sought size and scale to gain bargaining power in relation to suppliers. It’s well documented that Walmart’s use of scanner technology allowed for real-time data on what products were selling in which markets, at which prices, during what periods of time. Because of their size and the quantity of transactions, they began to get even better data on products than the manufacturers of those products had. This allowed them to gain significant leverage over those manufacturers in bargaining for prices. So Walmart began to get lower prices from Procter and Gamble, Nestle, and a whole range of other grocery products manufacturers. Companies like Kroger, Safeway, and Albertsons emulated this strategy.

In 2015, Albertsons acquired Safeway. Now Kroger is proposing to acquire Albertsons, which would make it just slightly smaller than Walmart in terms of grocery sales nationally. In places like California, Denver, Chicago, and other big metro areas in the United States, Kroger and Albertsons are together much bigger than Walmart.

ae: There is a similarity to other union labor markets, such as in auto or long-haul trucking: growth of the non-union market, which the firms beholden to union contracts respond to by consolidating in order to increase bargaining power against the union.

You mentioned barcode scanners. To what degree is technology another force for consolidation in play here? Usually people tend to think of consolidating ownership and technological innovation as things that reduce employment. Did that happen here?

jm: The labor reductions associated with the introduction of barcode scanners were relatively modest but that technology did give retailers significant new data regarding product sales, which allowed them to eventually negotiate better prices from manufacturers and to manage inventory much more efficiently. It also gave retailers much greater information about customer traffic patterns and gave them more confidence in their attempts to project the ebbs and flows of in-store labor demand, which contributed to the push toward greater volatility in workers’ schedules and the growth of the part-time segment. There’s evidence that, in addition to undermining worker stability, just-in-time scheduling is also counterproductive from an operations perspective because it inevitably leads to understaffing, but employers do it anyway.

E-commerce is of course a major technologically-driven development. In 2017, a very significant event occurred in the industry, and that was the acquisition of Whole Foods by Amazon. Up to that point, e-commerce for groceries was a very small part of the market. It had been tried during the dot com bubble of the late 1990s; a company called Webvan attempted to become an online seller of groceries and it resulted in a spectacular failure.

But because of Amazon’s significant size, power, and technical prowess, it was assumed that it would be able to crack the code. It’s also notable that the e-commerce market was and remains targeted at higher income consumers, which is very well matched with Whole Foods’ existing customer base. And so it was thought that the Whole Foods stores were well positioned to get to those shoppers. That was in 2017, and despite the fact that there’s been seven years now of Amazon’s ownership of Whole Foods, it hasn’t exactly worked out that way. The grocery industry is still trying to figure out how to make deliveries on an e-commerce basis profitable.

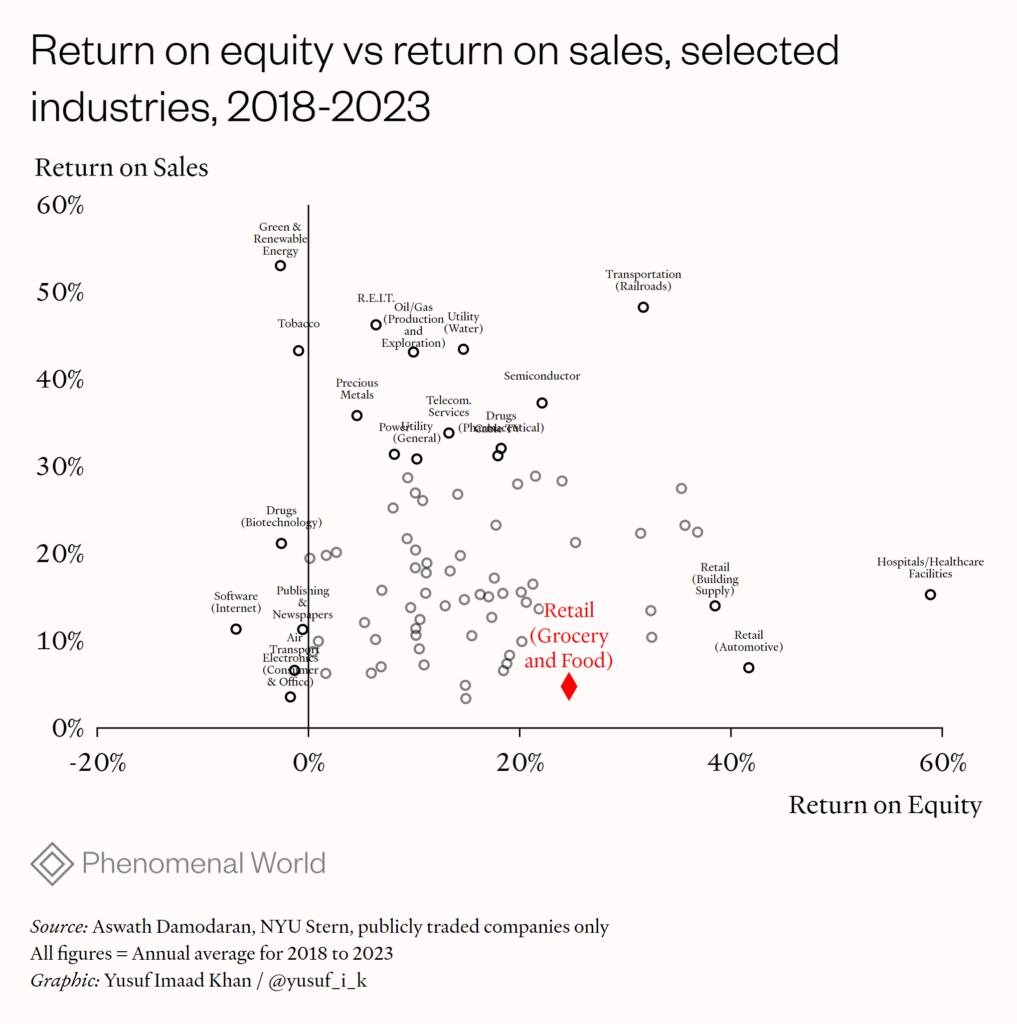

In addition to the physical characteristics of food, which make it, unlike books, very difficult to deliver securely, the margin on food is relatively small. When Amazon went into books and other general merchandise categories with significant sales margins, it had a real opportunity to be cost competitive, even with delivery costs added into the equation. Sales margins for food, on the other hand, are two or three percent.

The employers have tried to offset the increased costs associated with e-commerce by reducing in-store staffing, resulting in longer lines at checkout and an increased use of self-checkout lanes—but self-checkout has created more problems, specifically increased shoplifting, and many customers simply don’t like it, so to some extent that’s backfired. Now Kroger is trying to outsource more in-store jobs to third-party franchise operations. They currently use this model with the in-store sushi bars, but now they want to expand it to floral, deli, fresh-cut fruit, and eventually other functions. Franchise outsourcing isn’t a “technology” in the strict sense of the term, but it is a classic fissuring technique that, along with gig misclassification, we are facing right now.

ae: But the supermarkets aren’t unprofitable, are they?

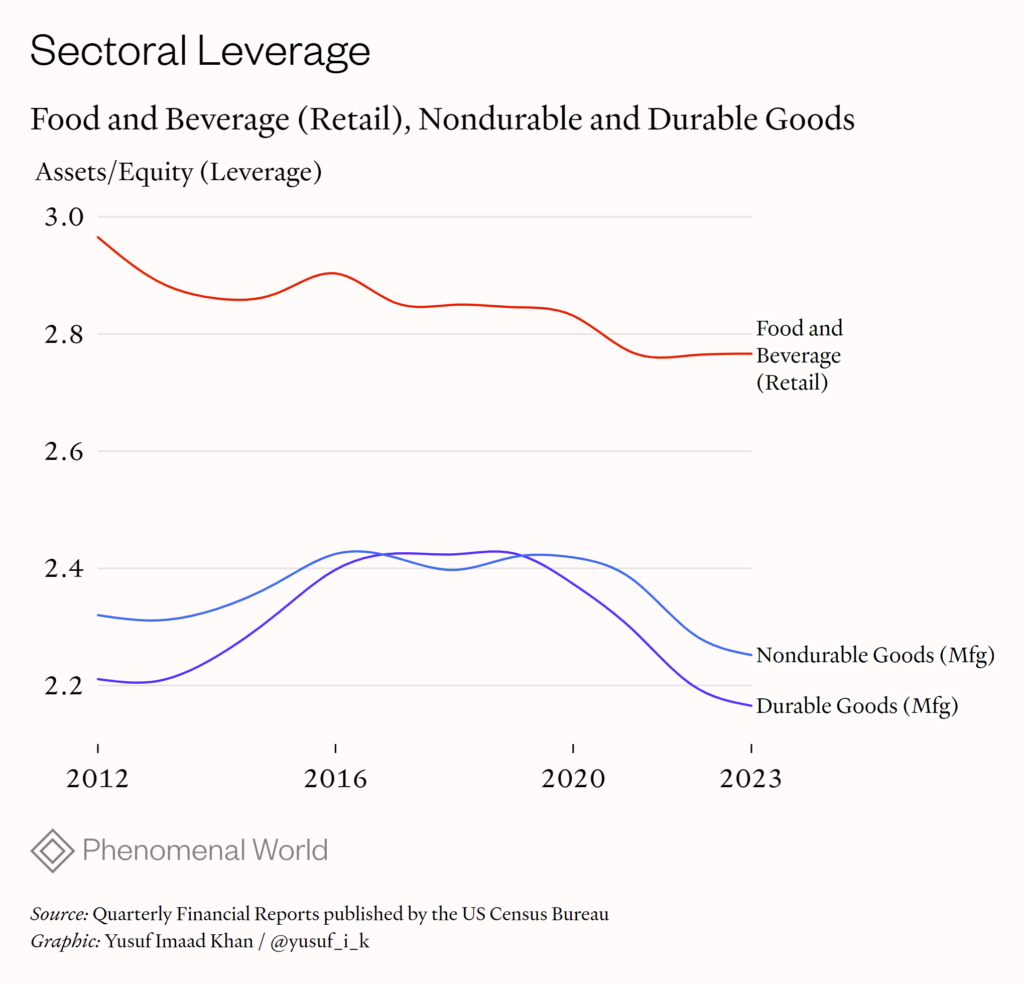

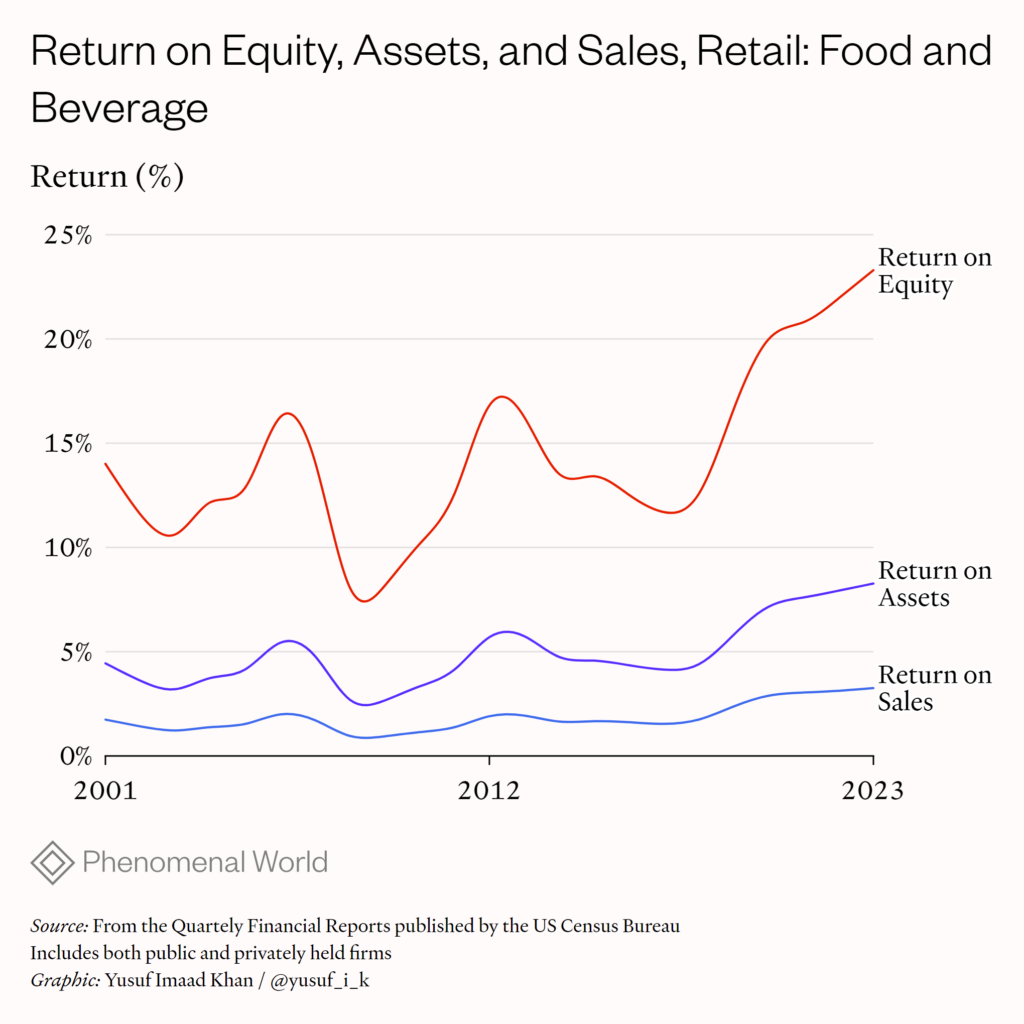

jm: No, supermarkets continue to be profitable. The margin on sales is relatively low in the sector—only 2 to 3 percent of every dollar spent on groceries represents profit to the grocer. But grocery store investors and the companies don’t primarily measure profits as a share of sales. They measure profits in terms of equity investment. And with the exception of the kinds of warehouses and technology in e-commerce, which I’ll get to in a moment, building grocery stores and maintaining them is not as significant an investment as many other industries. Return on assets and return on equity in the supermarket industry, which is a more important measure of profitability for investors, is toward the top of all industries in the economy.

The reason return on equity, in particular, is so high is not only because the capital investments typically required are less significant, it’s also because the grocery industry tends to be very stable through economic cycles. It is even counter cyclical in some ways. If you’re a lender, you look at a grocery store and you think, ah, this is a company that’s a safe credit even during a recession. Typically, supermarket chains have had more debt, all else equal, than other businesses.

Because they’ve been able to finance themselves with cheaper debt, the equity investors in grocery stores have been able to generate larger returns on their equity investments. The expectation is when the existing debt comes due, they’ll be able to roll it over into more debt and typically that’s what they’ve been able to do, as long as they continue to have good business prospects. If you’re well run, and you are not targeting a more discretionary, higher-end, and luxury consumer, but one that’s relatively immune to the business cycle, usually you’re able to use debt very safely.

ae: So, 2 to 3 percent net margin and what is return on equity?

jm: Over the past several years publicly traded US food retailers have reported an average return on equity of approximately 25 percent.

ae: What is the pressure to consolidate further? Having 25 percent returns on equity seems very lucrative.

jm: It’s been very profitable historically. But I think they are concerned that the industry is going to change, and they see themselves potentially benefiting from that change. Retail grocery has a quality that is very attractive to companies like Amazon: volume. Consumers purchase food much more frequently than they purchase books or electronics or other general merchandise. The frequency of that business makes it desirable for a firm like Amazon because there are cross-selling opportunities: “Oh, it’s Sunday and you’re buying eggs and milk, would you like a phone charger with that?”

That’s Amazon’s vision, and their entry in 2017 made supermarket executives and investors fearful that they were going to lose significant market share if they didn’t also have the ability to provide this service to consumers. That threat led to new partnerships and new investments in 2018 and 2019, which accelerated with the explosion of delivery demand in 2020 due to Covid.

ae: Is the predicted large shift to e-commerce happening?

jm: It hasn’t taken off the way it was expected to. Kroger is now into its sixth year trying a capital-intensive, semi-automated model in partnership with the British firm Ocado, and it still has not penciled out—just this March, Kroger announced the closure of three e-commerce facilities. Despite its significant investment in e-commerce capacity, it’s only 8 percent of Kroger’s sales.

In addition to the very significant capital investment associated with building warehouses and robots, and the additional delivery labor, the problem is that—aside from the temporary burst in 2020, and the relatively small thirty-minute delivery market—there’s just not enough demand to justify building warehouses the size of three football fields. But that’s what Kroger is doing with Ocado.

One reason companies like Kroger have continued to invest in e-commerce is that they see it as a stepping stone to new advertising revenue streams. Because e-commerce sales are conducted through a smartphone application or a computer screen it introduces an important opportunity for brands to reach consumers right at the point of purchase. That means Kroger can sell banner ads and search engine optimization to Nestle, Proctor & Gamble, etc. Kroger touts its ability to personalize these ads and help advertisers target them at precise demographic audiences based on the first party data Kroger and other retailers collect from customers. This is already a multi-billion-dollar industry and it’s projected to grow significantly. So Kroger hopes this new revenue stream will offset the higher costs associated with e-commerce fulfillment.

ae: Has Albertsons also made large commitments in this area?

jm: Along with its e-commerce initiatives, Albertsons is seeking to capture advertising revenues associated with online sales and all the customer data it collects. Like Kroger, it also launched its own retail media effort—Albertsons Media Collective—in late 2021.6

In terms of grocery sales, as opposed to selling advertising space and data, Albertsons’ e-commerce relies mainly on third-party gig delivery platforms like Instacart and DoorDash. They have a small partnership with a company called Takeoff Technologies that builds and services what’s called a micro fulfillment center (MFC). Basically adjacent to an existing grocery store, there is this vertical hive of bins with different kinds of products inside them, which are automatically selected onto a conveyor belt. The conveyor belt will be brought to a human picker, who will then pick items from each of these bins and put them into a customer’s tote bag. The tote bag will then be available either for pickup by the customer or for delivery by a misclassified gig worker from DoorDash or Instacart.

MFC’s require significantly less capital investment than the model used by Ocado, but they don’t work for many of the most popular selling items: bananas and broccoli crowns are too fragile; bottled water and paper towels are too bulky. This results in a situation where you can automate part of a customer’s order, but that has to be combined with items manually picked by a human worker. So when you visit these micro fulfillment centers in Safeway stores owned by Albertsons, the first thing you notice is lots and lots of workers, right?

This is increasing, rather than eliminating labor—which the firms admit. And this is before you get to the cost of investing in the MFC, the royalties that have to be paid to software developers, and so on. Analysts will ask on earnings calls about expanding these systems, and Albertsons executives just avoid the question. They’ve been doing it for four years, and I think have only six or seven throughout a network of 2,200 stores.7

ae: Was it evident in the summer and fall of 2022—when the merger agreement was signed—that all of these expectations about e-commerce were being disappointed? Is the merger a recommitment to this soft market, to try and manage excess capacity?

jm: Yes, it’s fair to say that relatively soon after Kroger began its partnership with Ocado, they acknowledged that it was performing below expectations and profitability remained a challenge. For Kroger, volume has been a real disappointment in its new e-commerce facilities, which I think is one of the primary reasons why they are attempting this very aggressive acquisition of their largest direct competitor, Albertsons. By combining Albertsons’ e-commerce sales with their existing e-commerce sales, I think they hope to get enough volume moving through these warehouses—and to achieve the level of delivery densities—to make the Ocado system profitable.

Kroger CEO Rodney McMullen is the one who chose to make this very significant investment in the automated warehouses with Ocado, and that is proving to have been a bad decision. I think he is personally motivated to find a way to make that investment pencil out. And my expectation is that it won’t, and that the merger will be blocked, and that Rodney McMullin’s days as the CEO of Kroger are numbered.

More broadly, real doubts remain about whether the data-driven expansion into e-commerce and retail media will be a successful strategy for the supermarkets. In addition to the deteriorating in-store experience I mentioned, it’s not clear that most consumers really want this model. Kroger says it is concerned about losing market share to Walmart and Amazon, but it’s the smaller regional chains that are in some ways a bigger threat because they’re doing a much better job at offering local products and a better in-store experience. Trader Joe’s is another example that’s often cited as a threat to Kroger and Albertsons’ market share, but look at the Trader Joe’s model: zero e-commerce, zero self-checkout. I’ve got a lot of problems with Trader Joe’s, particularly the company’s illegal threats and interrogation of workers trying to form a union, but the company is an example of a successful business model that rejects in-store automation and surveillance capitalism.

ae: You mentioned Walmart’s expansion into food during the 1990s and 2000s as a source of competitive pressure on grocery retailers. Yet you also mentioned the geographic nature of grocery markets. And so I wonder with all these other segments in the market, different clientele, and different geographic markets, to what degree is this variation in firm strategy introducing competition in the market, as opposed to segmenting the market. It sounds like Trader Joe’s is taking Kroger’s customers.

jm: This is significant in the context of the antitrust case. What we know is that customers who shop at Trader Joe’s also continue to shop at Safeway and Kroger, because you can’t get everything you might want at Trader Joe’s. Trader Joe’s has far fewer items for sale versus a traditional Safeway or a Ralph’s.

To some extent this is also the argument that UFCW made in 2003, during the strike in Southern California. The threat of competition from Walmart was anticipated, but not yet real. Walmart had not, certainly not in 2003, and to some extent still not today, succeeded in penetrating the large coastal urban markets, whether it’s New York, or Los Angeles, or San Francisco, or Seattle. Now they have a modest presence, but for a number of reasons—not least the opposition that the United Food and Commercial Workers Union presented—Walmart’s market share in places like New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Seattle is much, much smaller than their market share in most of the other markets where they compete.

But the real problem with Kroger and Albertsons isn’t that nontraditional retailers like Trader Joe’s are taking away their market share, it’s that Kroger and Albertsons haven’t been opening new stores while other retailers have. Instead, Kroger and Albertsons have spent billions of dollars on massive dividends and share buybacks.

ae: What about the labor market? One of the FTC’s arguments is that Kroger purchasing Albertsons will reduce competition for hiring workers. Of about twenty pages of argument, five of them are spent making the case that combining the two largest unionized retail grocers will reduce demand for union labor, that they set their wages based on what their competitors are doing, and that in negotiating labor contracts this competition strengthens unions at the bargaining table. It lists union contracts for something like 70 counties across four states where Kroger and Albertsons are signatories together employing over 65 percent of the retail grocery workforce. The companies disregard this and say the merger, by allowing the combined Kroger-Albertsons to compete with non-union companies like Walmart, will actually be good for workers. Is it a common labor market or is the labor market also segmented? Who comprises the labor market for grocery retail?

jm: It’s segmented across a number of dimensions. One significant dimension now is that particularly in large metro markets, in places like California, Seattle, and Denver, a large share of the workers are in the union, and so there’s the collective bargaining market. For workers, that market has significant benefits that the nonunion sector lacks, particularly when it comes to retirement and health care benefits. Wages for employees who have been there for a number of years are also higher. Wages at the starting level are more comparable between the union and nonunion sector, unfortunately, but the benefits are far superior.

What we’ve typically seen is that older workers—workers who are thinking about retirement, thinking about the need for healthcare, particularly family healthcare—are much more attracted to work in the union sector, and once they’re in the union sector and have those benefits, they don’t want to leave.

During the Covid pandemic, with restaurants shut down and supply chains disrupted, significant questions emerged regarding the economy’s ability to continue to provide essential food to the population. It was an important moment for grocery workers. They were, for the first time, considered to be essential workers, because of the critical nature of their role at that point in time. And that was important to elevate the status, and even the standards in some cases, of work in the industry.

It’s a huge advance that the FTC has used the collective bargaining market as a distinct market for the purposes of their labor argument in their opposition to the Kroger-Albertsons merger. The FTC is correct in doing so: the collective bargaining agreements cover the majority of the workers at the two companies, and the wages and benefits in those agreements are established through collective bargaining between the union and the two companies. Currently the union is able to play the two companies off against one another in order to make improvements in the contracts, but if there were only one company, Kroger, that power would vanish. So the FTC is acknowledging that reality, and that is, as far as I’m aware, unprecedented.

FootnotesBeginning in the Reagan recession, Kroger made its first of several large acquisitions with Dillion Companies, the holding company for western grocers King Soopers, City Market, and Fry’s. At the peak of the Clinton-Greenspan stock market bubble in the late nineties, Albertsons purchased American Stores, owner of northeastern chains Lucky and Acme followed by Kroger’s acquisition of Fred Meyer, the owner of west-coast grocers Ralphs, Food 4 Less, and others. Both Albertsons and Kroger embarked on a new wave of acquisitions in the aftermath of the global financial crisis: Kroger bought the southeastern grocery chain Harris Teeter in 2014 and the upper midwestern Roundy’s in 2015; Albertsons bough the North Texas and Oklahoma chain United and Market Street in 2013 and the mega company Safeway, owner of Randalls and Vons, among others, in 2015.

These are: Walmart, Kroger, Costco, Albertsons, Ahold Delhaize (Stop and Shop and Food Lion), Publix, Aldi, and Target. https://www.businessinsider.com/profile-of-amazons-new-retail-ceo-doug-herrington-2022-7 The US Department of Agriculture found the top 8 firms in food retail surpassed 50 percent of sales around 2015. https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/105558/err-314.pdf?v=8617.4 The Guardian, in partnership with Food and Water Watch, found a significantly higher degree of concentration in food and beverage sales: the top 4 firms had 69 percent of sales in 2019. https://www.foodandwaterwatch.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/IB_2111_FoodMonoSeries1-SUPERMARKETS.pdf

The FTC scheduled its own hearing to determine whether the companies were violating the antitrust laws for July 31. On March 11, Kroger, represented by Arnold and Porter and two other firms, and Albertsons, represented by Debevois and Plimpton and three other firms, sought and won delay in the District Court hearing for a preliminary injunction until August 26. On March 26, Kroger and Albertsons filed a motion to delay the FTC hearing from July 31 to October 21, which the FTC denied on a 3-2 party-line vote. Attorneys general of Colorado and Washington have also filed independent cases in their state courts seeking to enjoin the merger, with hearings scheduled for August 12 and September 16, respectively. In compiling their cases, Kroger and Albertsons are collecting their own third-party discovery on companies such as Walmart, Costco, and Amazon to make the argument that the merger is necessary to preserve competition against such general retailers moving into food. In the words of Matthew Wolf of Arnold and Porter, allowing Kroger to purchase Albertsons is “important for the future of the American corner grocery store.”

Supermarkets are a subset of grocery stores. Does not include 53,000 establishments in “General Merchandise” employing another 2.4 million workers. Of this employment, 98 percent came from less than 1 percent of firms.

In 2023, the Bureau of Economic Analysis reported personal consumption expenditures (PCE) for food and beverages consumed off premises of $1.44 trillion.

Eds: According to Adweek, the “Albertsons Media Collective is a retail media network that delivers engaging digital and branded shopper-centric content to over 100 million shoppers and loyalty program members of Albertsons Companies’ 24 retail store brands in 34 states and the District of Columbia. Albertsons Media Collective digital platform connects brands with loyal shoppers through omnichannel solutions including native display and sponsored product inventory.”

Eds: On May 30, after this interview, Takeoff Technologies declared bankruptcy.

Filed Under