The uptick in organized and unorganized labor militancy registered throughout the pandemic, and in particular in strike and unionization campaigns in recent months, comes at a relative nadir for the US labor movement. The work of Kim Voss, Professor of Sociology at UC Berkeley, brings the current moment into sharper focus against the longer and particular histories of worker organization in the United States—from nineteenth century workers’ organizations to more recent alliances between unions and social movements.

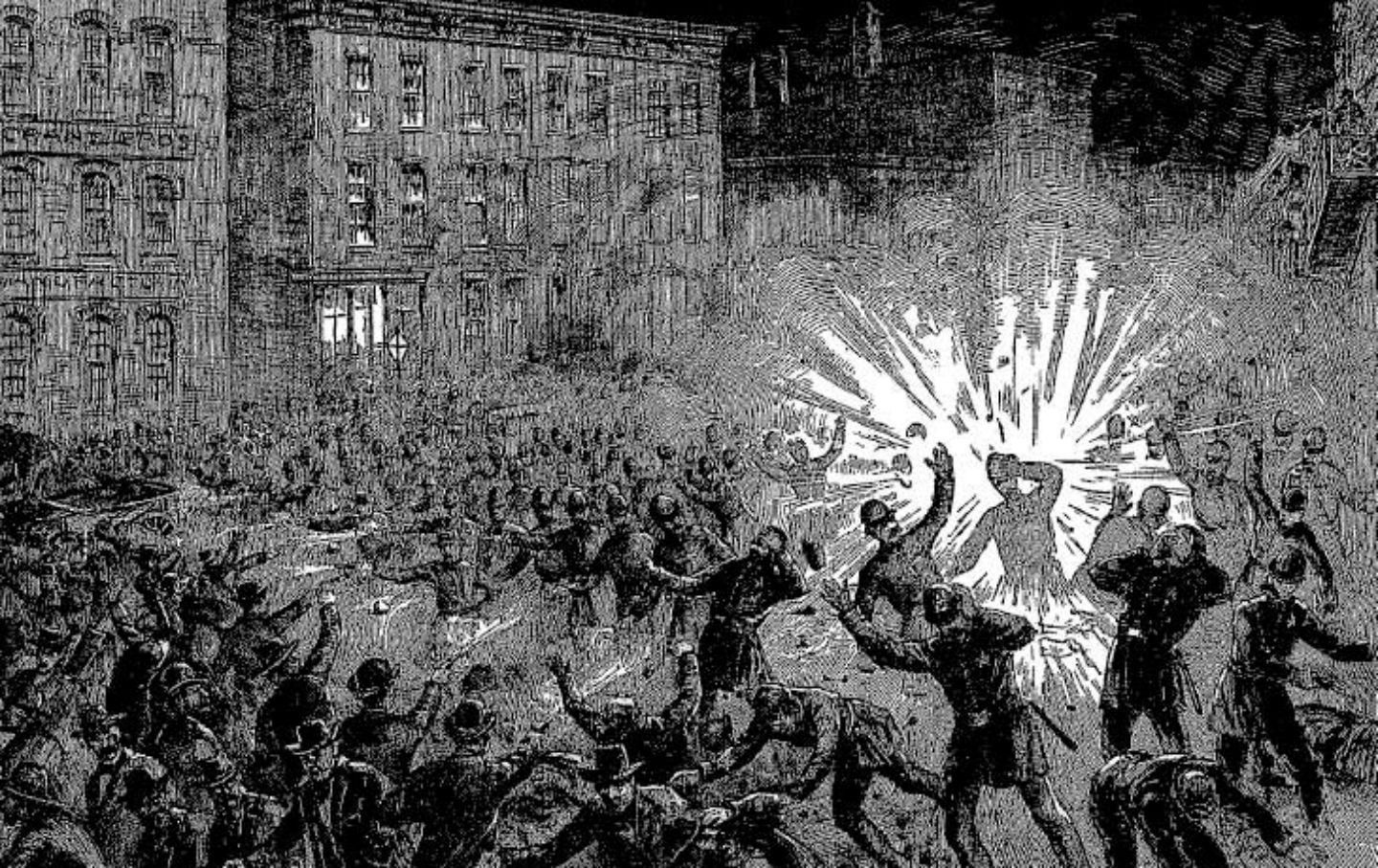

Voss’s 1993 book, The Making of American Exceptionalism, argues against theories which attribute the labor movement’s weak and conservative character to factors like the individualist nature of American culture or the structure of the American economy. In doing so, she follows in the tradition of scholars like Werner Sombart, who emphasize the historical contingency of capitalist development. Voss traces the divergence between the American labor movement and its European counterparts to 1886, when powerful employers coordinated with the state to crush the progressive Knights of Labor.

Her later work focuses primarily on strategies for union revitalization; the 2004 book Rebuilding Labor, co-edited with Ruth Milkman, considers the state of union democracy, conditions of membership recruitment, effectiveness of union leadership, and degree of anti-union sentiment among contemporary workers. Hard Work, published the same year and co-authored with Rick Fantasia, focuses on the emergence of “social movement unionism” in cities like Los Angeles and Las Vegas, arguing that even in a hostile terrain, trade unions which form strong community ties and are able to integrate labor demands with broader social aims may have a hopeful path forward.

We spoke in November about turning points in the history of the American labor movement and the recent events of “Striketober.”

An interview with Kim Voss

Maya adereth: The notion of American Exceptionalism—the idea that US economic and political systems are unique from those of other rich democracies—frames your work on the Knights of Labor. Did this idea ever have resonance, and if so, does it still have any today?

KIM VOSS: American Exceptionalism has always been a fraught term used in many different ways—politicians and pundits tend to use it to exalt the US political system, while scholars often point out that it’s not altogether that special, and others sometimes use the term to highlight the failings of American democracy. My entry into the debate was specifying which type of exceptionalism we’re talking about. With respect to labor, it’s accurate to say that the American labor movement has been broadly less progressive than comparable movements. Episodically, there have been higher levels of militancy, but this didn’t result in a politically strong and inclusive labor movement. In my book, The Making of American Exceptionalism, I argue that it didn’t have to be this way. Especially if we go back to the last three decades of the nineteenth century, we can see that there were other possibilities for development, and periods in which the American labor movement advanced in an inclusive and progressive direction.

MA: You demonstrate a similar resistance to stagnant categories in thinking about the labor movement. Eric Hobsbawm famously developed the idea of the labor aristocracy; a layer of organized craft workers who organize along sectional lines. You take a far more flexible view, arguing that local conditions may lead craft workers to take more inclusive or exclusive strategies in different moments. What are the different strategies available to unions, and what might lead them to adopt one over another?

KV: My instinct of course is to immediately historicize the question. If we look at how social movements, and especially labor movements, mobilized in the late nineteenth century, craft workers (the so-called labor aristocracy) were more able to advance their program simply because they had more resources to build on. But there were crucial moments in which they made common cause with less privileged workers, such as when the Knights of Labor used the language of egalitarian democracy to fight for labor rights and when they mobilized community ties to build solidarity across skill level, nationality, and gender. Part of the reason why this didn’t occur more frequently is because of the organization of powerful employers and the way in which the government responded to moments of labor militancy—the state only intervened episodically in labor struggles, but when it did it was always against broad-based mobilization. So, when the Knights of Labor did successfully organize skilled and less-skilled workers together in strikes against concentrated corporate power, the state either did nothing to constrain employers’ actions or it brutally repressed workers.

The lesson that labor leaders and activists draw from this was that it would be impossible to win by organizing a mass movement. This lesson structured the orientation of the majority of labor leaders in the American labor movement for generations; there wasn’t a big upsurge of mobilization for progressive change again until the 1930s. And even after the creation of industrial unions, when the labor movement campaigned for broad universal demands like healthcare and pensions in the 1940s, it was pushed back. The result was the construction of what I and others have called a private welfare state. By using collective bargaining to gain things like medical benefits, employment security, and pensions, trade unions were able for a while to offer members a private alternative to the public system of social provision. But in the long run, this proved to be a losing strategy, because it divided organized from unorganized and privileged from unprivileged workers.

MA: There are a number of factors which come up frequently in explaining this push back, two of which you have written about extensively. The first is immigration, and in particular the widespread hostility towards immigrants from China, Japan, and Korea, that’s pervasive in the AFL literature. The language they used is familiar to a contemporary ear: immigrants flooding the market with cheap labor and undermining the bargaining power of organized workers. What sort of relationship has the American labor movement historically had to immigration, and when have these sorts of cleavages been overcome?

KV: My current work, which I’m doing with Irene Bloemraad, is a theoretically informed, comparative examination of immigrants and social movements, although not just from a labor perspective. The key contradiction informing this work is between the deep and persistent hostility towards immigration that we see across American working class organizations, and the narrative of the “nation of immigrants” which is periodically conjured by government representatives. In the early AFL documents that you allude to, anti-immigrant sentiments go hand in hand with the organization’s craft orientation: the same reasoning which drives leaders like Samuel Gompers to advance sectional interests of skilled workers paints low-wage, nonunionized immigrant workers as a threat to tight labor markets. An interesting detail in the work of the historian Donna Gabaccia is that the term, “nation of immigrants,” was first used in the Civil War decades to justify the exclusion of immigrants, typically referring to “undesirable” workers from China and southern Europe and often using the term in a nativist context; it was only used as a phrase to celebrate inclusiveness much later, during the reform years of the late 1960s. Though Americans have been conceptualizing themselves as a nation of immigrants for centuries, this concept has been politicized in different ways at different moments.

Though the American labor movement was overwhelmingly anti-immigrant, there were notable moments of inclusiveness on the part of unions. The Knights, of course, had their own opposition to Chinese migrant labor, but still organized immigrant workers. And AFL affiliates like the International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union were at the forefront of organizing low-wage immigrant workers in the early twentieth century and innovating strategies to resist deportation in the 1970s. It’s useful to remember that the AFL-CIO has always had little control over its national unions, and the national unions bear little direct influence on the locals, so we do have all of these internal struggles. Why were the Garment Workers so far to the left on deportations and other issues in the 1970s? Part of it is that their leadership had a commitment to labor solidarity, but the other part was that so long as the government was conducting raids on the garment industry, they couldn’t organize without defending the rights of undocumented immigrant workers. In the early twentieth century, leaders of ILGWU faced resistance from the immigrant, low-wage, and largely female rank-and-file textile workers, and the union had to adapt to an industrial strategy.

MA: The other element is the immense power of US employers. Historically, American employers have not only been well organized, but have had direct influence on the interventions of the state. Can you talk about the role of employers in shaping the organizational strategies available to workers?

KV: American employers have always been better resourced than employers in many other rich democracies, and they have also usually been able to count on the state as a partner. If we compare the American labor movement to the French or British one in the last decades of the nineteenth century, we see that in France and Britain, the state did occasionally intervene directly or behind the scenes to demand employer concessions; when the American state did intermittently intervene, it was unfailingly on the side of employers until the New Deal era.

It’s important to remember that the US state in the nineteenth century was a very different kind of state. Stephen Skowronek characterizes it as a system of “courts and parties,” meaning that it didn’t have many of the bureaucratic and infrastructural features of many European governments. Nevertheless, when it sent the military to attack strikers, as it did in 1886, it played a decisive role in shaping moments of upsurge.

In the twentieth century, after the organization of the CIO and the establishment of the legal right to form a union, employers’ strategies shifted. They first acquiesced to a new institutionalized process for recognizing unions—and then learned to use those rules to their advantage. Today, the union certification process for private sector firms in the US is an adversarial process of majority recognition; the only way workers can join a union is if they can convince a majority of their coworkers to vote for a union, usually in an election overseen by the government.

Employers have a say in who is and is not eligible to vote, and they are legally allowed to mount fierce anti-union campaigns in which they threaten and intimidate workers, both collectively and in required one-on-one meetings. For these campaigns, employers can—and often do—turn to a sophisticated industry worth hundreds of millions of dollars per year devoted to helping employers resist organizing drives. If even all these employer advantages are not enough to prevent union recognition, bosses have formal procedures for deunionization at their disposal, procedures unheard of in other rich democracies. Should workers persist in the face of these many obstacles, employers have the legal power to permanently replace them if they go on strike. These advantages most definitely shape the organizational strategies available to workers, requiring unions to design comprehensive and innovative campaigns, even as they grapple with the kind of structural changes in the economy that are destabilizing labor movements across the globe.

MA: I wanted to ask about innovation in labor strategy, and how organizing tactics reflect broader relationships between workers and employers. The Services Employees International Union (SEIU), which took off in the 1990s, for example, has often been criticized for relying on public relations and top-down negotiating strategies. What does the SEIU tell us about recent American labor history?

KV: There are a lot of critiques about SEIU out there, in part because it’s one of the few U.S. unions in recent years that has been aggressively trying new ways to build the labor movement. Its rise comes down to a couple of different factors: one is that it recruited activists from other movements, such as the Civil Rights and the women’s movements in the 1970s, and campus activism and identity movements in the 1980s and 1990s. These activists, along with others in the union, interpreted labor’s crisis as a mandate to transform union goals and tactics. Another factor is that SEIU spanned the public and private sectors, so they could leverage resources from one to strengthen organizing in the other. SEIU used its resources to launch audacious and innovative campaigns, like the Justice for Janitors campaigns. The janitorial industry had once been heavily organized but by the 1980s, unionization had been completely decimated by subcontracting. At a time when other unions had given up trying to organize such industries, SEIU figured out a way by designing a corporate campaign and mobilizing a largely immigrant workforce. Because immigrant workers played a big role in the successful Justice for Janitors campaigns, other unions changed the way they related to immigrant workers—there was even a period when unions across the AFL-CIO concluded that immigrant workers were the key to successful organizing.

Another SEIU campaign that yielded significant success is the Fight for $15 movement, an ongoing effort that has led to a higher minimum wage in many US communities and states and an effort that continues to spark activism in many low-wage workplaces.

Does SEIU always get it right? No. Some critiques that it has relied too heavily on top-down negotiating strategies in some of its campaigns are justified. Has SEIU sometimes neglected bottom-up strategies, even turning against the rank and file? Yes. However, we have to understand SEIU’s inadequacies not simply by turning to the usual suspects, such as flawed leaders or deficient politics, but instead we must consider the ways that capitalism itself has changed. With financialization of the economy and atomization of workplaces, it has become increasingly difficult to generate the kind of employer response to workplace actions that was key in the 1930s. As Pablo Gaston and I have argued, financialization and other economic trends have undermined the leverage that workplace actions alone can provide. As a result, organizing campaigns can succeed only when they synthesize and combine top-down and bottom-up approaches, and sometimes not even then.

MA: How have the transition to service sector work, automation of job oversight, and financialization changed the strategies labor unions should pursue? Amazon is on everyone’s minds, and previously it was Walmart.

KV: The labor movement hasn’t come up with a strategy for organizing Walmart, and the best analysis I’ve seen is in the book Working for Respect by Adam Reich and Peter Bearman. They point to the challenges presented by Walmart’s huge scale, as well as to what they dub, “walmartism,” a managerial strategy of control that results in an autocratic workplace where it is very difficult to build and sustain relationships among coworkers.

How do social movements come up with new strategies for social change? One thing I’m sure about is that you can’t organize Walmart or Amazon one store or warehouse at a time. The lesson I draw from the scholarship on labor movement revitalization is that it will take a comprehensive strategy, one that combines an analysis of Walmart’s and Amazon’s corporate vulnerabilities with an on-the-ground strategy of small successes to show workers that it’s worth risking their livelihood for a union. Currently, with respect to Walmart and Amazon, we are where the activists that innovated the Justice for Janitors campaign were in the late 1980s. No union or activist that I know of has yet put together the bottom-up and top-down pieces, but I have to believe it’s possible.

MA: We’ve just seen this uptick in worker militancy and strike action in John Deere, Kellogg, Kaiser Permanente, and other workplaces across the country. How can we understand this moment, and what does it indicate for US labor movements in the coming years?

KV: Clearly one of the things that is playing out here is the pandemic, and the rhetoric about essential workers and their sacrifices. Once employers saw improvements in their economic situations, these sacrifices on the part of workers were neither acknowledged nor compensated. Workers understandably feel betrayed and angry, which are key factors driving the strikes. In addition, workers sense that they are in a stronger strategic position now, and thus, many believe that strikes are winnable.

Where do we go from here? How much can we expect to see a larger wave? The more these actions succeed, the more of them we’re going to see. While the numbers we’re seeing now are impressive, they don’t come anywhere near earlier strike waves. Nor have they resulted in new unions or growth in existing unions, as the strike waves of the 1930s did. Of course, we have to celebrate successes. But it will take a heck of a lot more success—and organizing—to build a movement.

Filed Under