The much anticipated “return to normal” after the Covid-19 pandemic has been anything but. In contrast to the aftermath of previous economic crises, workers have not rushed back to work. Each month over a period of nine months in 2021, an average of four million people in the United States left their jobs. Similar trends were reported elsewhere. Resignation rates and job changes have been at a historical high in the UK; rates are rising in other wealthy countries like France, Australia, Netherlands, Spain, and even Singapore.

“The Great Resignation,” as the US trend was named in May 2021, attempts to summarize these shifts in employment. The term also carries major implications for fiscal and monetary policy. The trend looms large as the hidden text behind the Federal Reserve’s (and other central bankers’) responses to inflationary pressures, even though there is ample evidence that other factors—global supply chain issues, the war in Ukraine and subsequent sanctions on Russia, energy prices and food shortages, and also profit-seeking and price gouging—are responsible for rising inflation worldwide.

In what follows, we highlight the gendered dimensions of “The Great Resignation” in both the United States and China, which have been mostly neglected thus far. Although there is a growing literature which shows that women tend to be more (and differently) affected by economic crises than men, analyses of “The Great Resignation” have so far largely overlooked the gender dynamic. In this context, gender-blind policy responses have thus created a pretext for recovery which ignores the needs of women and minority workers.

The Covid-19 pandemic has led to a much higher rate of job losses in the United States than in Europe or Asia. The recession that followed was deeper than that of the global financial crisis (GFC) and its distributional effects were far more uneven—job losses and deaths were disproportionately concentrated in low-income groups, and among women, Hispanics and African-Americans. Women accounted for 70.8 percent of workplace illness caused by viruses in 2020. Their labor participation in April 2020 declined to 54.6 percent, the lowest since 1987 (it increased to 58.1 percent by December 2022, but remained below the 59.3 percent participation in February 2020).

US government programs including the CARES Act and American Rescue Plan reversed the course of the recession faster than in the GFC, allowing for quicker return to work. And yet, the workers did not come. In 2021, more than 47.8 million US workers quit their jobs. Analyses of unemployment rate and job openings indicated an increasingly “tight labor market” and its close correlation with the quit rate, as measured by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS).1 But BLS analysts also warned that the US quit rate in 2021—which stood at approximately 3 percent of the workforce—may not have been the highest historically. Similarly, two Harvard Business School professors convincingly argued that the quit rate in the United States had been creeping up ever since the GFC, leading The Economist to headline that “the evidence for The Great Resignation is thin on the ground.”

A “Great Resignation”?

We examined more than 150 articles covering “The Great Resignation” published in major US newspapers in 2021 and 2022. Most focused on professionals, explaining the crisis as the result of pandemic epiphany, changing life priorities, as well as government support and the (relatively) high rate of savings accumulated during lockdowns. Additional explanations emphasized the desire for higher pay, greater flexibility, and pursuit of better career opportunities. Although women frequently featured as “human interest” subjects in the media coverage of “The Great Resignation,” gender was rarely mentioned as a factor correlated with job quitting.

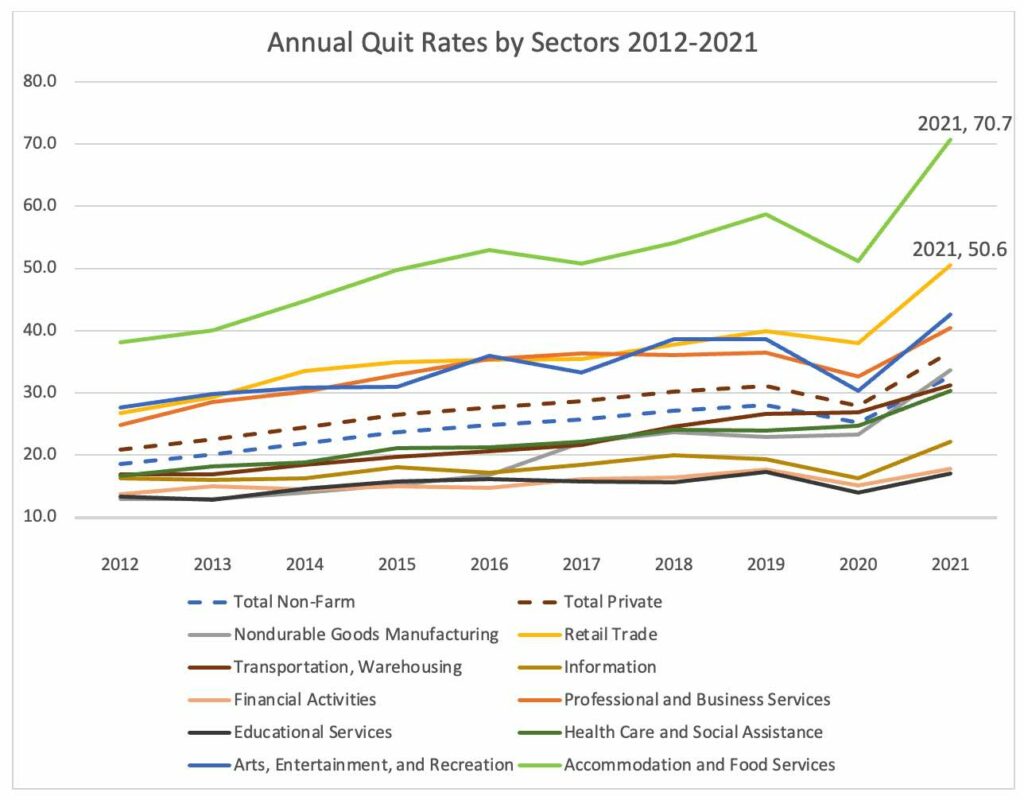

The media coverage was greatly influenced by widely-cited surveys conducted by private corporations, such as Microsoft’s Work Trend Index and “Global Workforce Hopes and Fears Survey,” administered by PricewaterhouseCoopers. While the surveys aimed to represent global employment trends, they over-represented professional and administrative workers in wealthy countries. A closer examination of available labor market data from BLS complicates these media and corporate narratives. Resignations have been most prevalent not in finance and information services, but rather in two sectors where employment rates are historically volatile: leisure and hospitality and retail trade. These were also the sectors where tele-commuting options were not available, and which—along with health care and transportation—carried significant risks of Covid-19 infection. They also have higher rates of female and immigrant labor. Accommodation and food services, where the rates of resignations were by far the highest in 2021 (70.7 percent), employs 52.5 percent women and 27.3 percent Hispanic workers. Monthly quit rates averaged 5.8 percent per month in 2022, up from 4.9 percent in 2019. The sector has traditionally depressed wages and low levels of unionization, and experienced massive layoffs at the start of the pandemic.

Figure 1 shows the data from 2012 until 2021 for the sectors with the highest quit rates. Frontline workers in accommodation and food services, retail, health care, and transportation were more likely to quit their jobs than others. As BLS economist Gittleman argues, “the recent quit rates are too high to be explained solely by labor market tightening.”

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Jobs and Labor Turnover Survey, https://www.bls.gov/jlt/data.htm

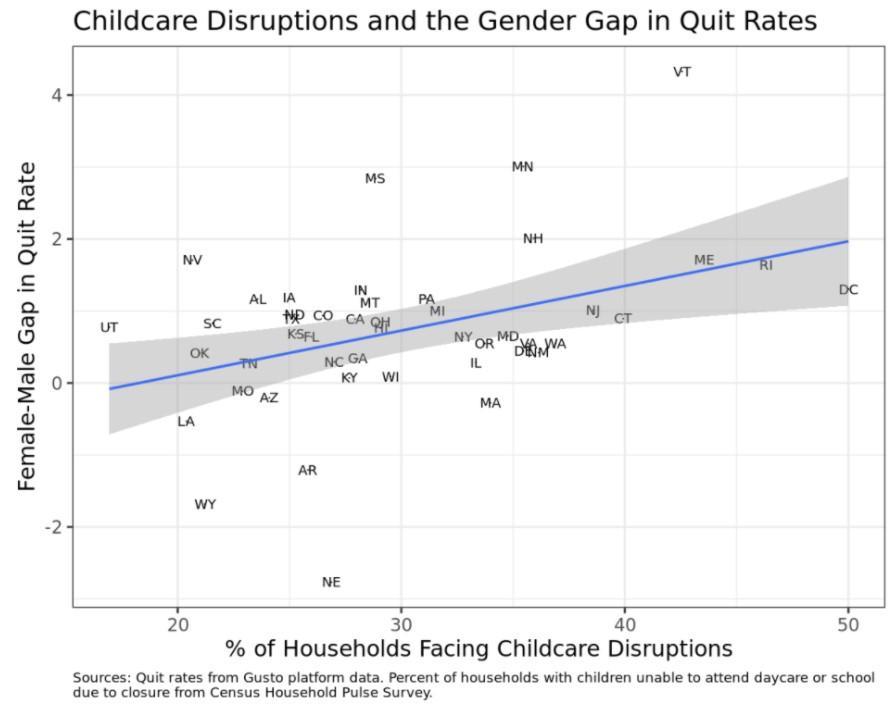

Other factors such as childcare and pandemic-related school closures, often invisible in mainstream economics, might have affected quit decisions. Analysis by Gusto found that the female quit rate was higher than the male rate (Figure 2), and women were more likely than men to quit their jobs due to school closures and childcare disruptions (Figure 3). States with the highest rates of disruption such as Maine and Rhode Island saw a gender gap of 1.7 percent.

BLS data also show that both men and women of working age who are not seeking jobs cite ill health and family responsibilities as their reasons for withdrawing from work. These same indicators had been declining in the years before the pandemic. And yet, the Biden Administration’s plans to include childcare and care for the elderly and disabled under the umbrella of infrastructure has failed in the US Congress. The US continues to lag behind the rest of the world when it comes to childcare provisions, ranking thirtieth (out of thirty-three) among OECD countries in public spending on families and children.

“Lying flat” (Tangping: 躺平) in China

In April 2021, a post on a social media platform Baidu titled “Lying Flat is Justice” went viral. The young Chinese urged their compatriots to opt out of a hypercompetitive work culture and resist social pressures to overwork. By “lying flat,” young workers did not quit jobs or exit the workforce, but instead they gave up promotion ambitions and greater economic returns. Rather than working full-time, some young workers chose flexible employment in the gig economy.

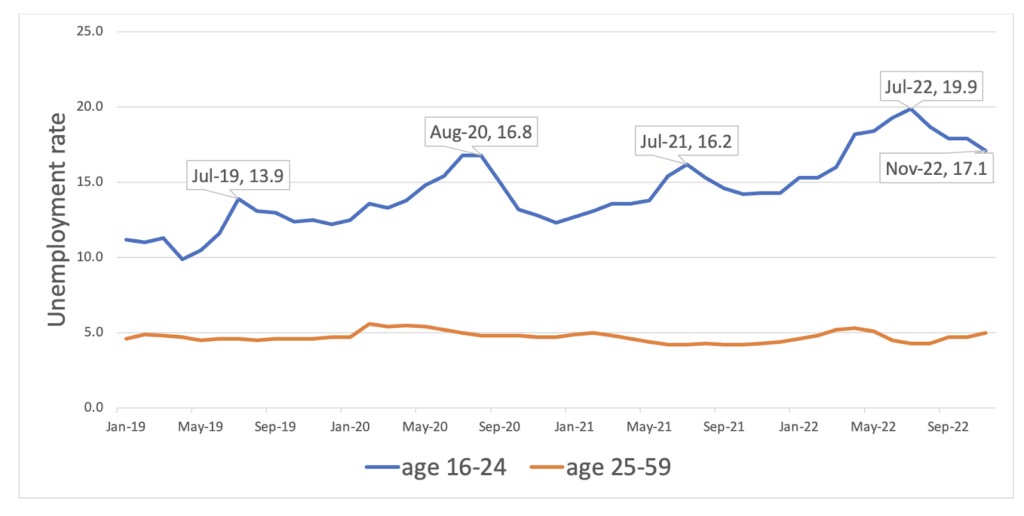

But “lying flat” was more than a personal choice. Severe unemployment among the young Chinese, in large part due to frequent lockdowns, was a contributing factor. According to the Unemployment Survey of the National Bureau of Statistics (Figure 4), the young Chinese (aged 16–24) unemployment rate was over 16 percent in July and August 2020 and July 2021. By July 2022, the rate had risen to 19.9 percent. The preference for “lying flat” clashed with President Xi Jinping’s ambitions to spur Chinese technological self-reliance and domestic consumption as the engines of economic growth. State news called “Tang ping” shameful, and “Tang ping” posts were deleted on social media. The protests in China, which erupted in December 2022—and led to the reversal of its long-standing zero-Covid policy—were in part fueled and galvanized by the discontent of the young Chinese.

Note: unemployment rates data are only available for the urban population.

Source: (China) National Bureau of Statistics

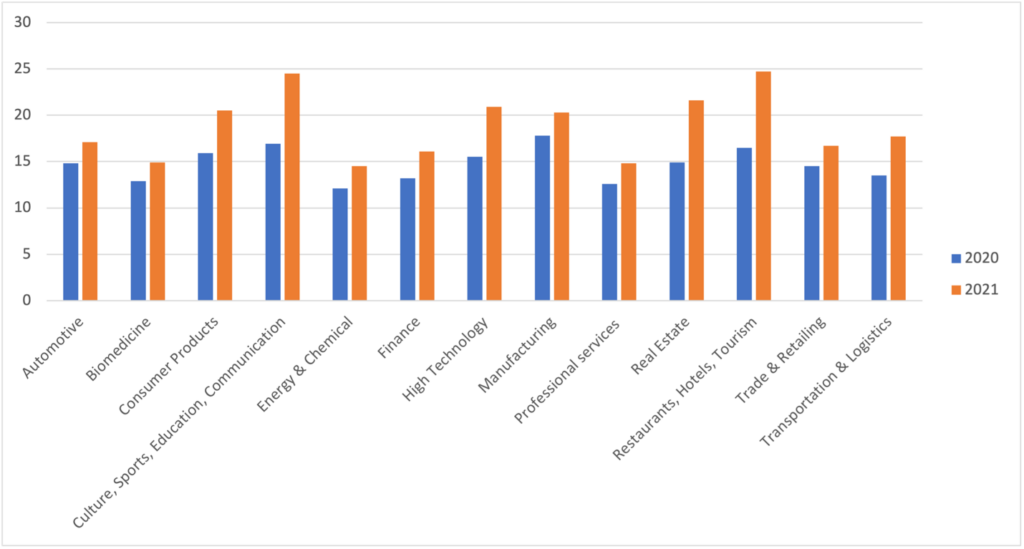

As elsewhere, the gender dynamics of China’s “lying flat” have been neglected. In China, female-concentrated sectors, such as restaurants, hotels, tourism and culture, sports, and communication have the highest turnover rates—close to 25 percent. In 2022, small businesses in restaurants, retail, and tourism remain at the “center” of the pandemic’s effects.

Note: turnover rate is the percentage of employees who have left a company over a certain period of time. It could be led by layoffs or quits.

Source: 2021 Human Resources White Paper, 51 job, http://research.51job.com

China’s new education policy in 2021, which banned for-profit tutoring in core school subjects, might explain the high turnover rate in education. China’s “zero-Covid” policy (Qingling: 清零 ) and “standstill” orders (Jingmo: 静默) also played an important role in women’s labor force exits. Like in the US, the shutdown of childcare services has exacerbated China’s existing shortage of childcare provisions, worsening women’s childcare burden and disrupting their working status. (A recent Deloitte survey showed that 30 percent of Chinese women viewed themselves as “the only person in their households able/available to do household management and childcare.”) Burnout and depression have also affected their resignation rates. Zhang Dandan finds that 10 percent of Chinese female workers left the workforce at the end of 2020, whereas men’s leaving rate was 5.7 percent. Women’s return to work was also slower than men’s.

Finally, the “three-child” policy released in 2021 to reverse declining population trends is likely to worsen gender discrimination in the labor market, with employers potentially more reluctant to take on female jobseekers. Many companies are suspicious of their female workers’ childbearing plans and thus discharge them or keep them in low-level positions to avoid potential costs. The Chinese government has proposed tax reductions and subsidies, parental leave, inclusive childcare services, and other measures to support the “three-child” policy. But these are likely to fall short: some measures, like parental leave extension, will be difficult to implement in China’s highly competitive and discriminative workplaces. The subsidies (1,500– 2,800 USD in total) will barely alleviate childrearing costs—raising a child to the age of 18 is 6.9 times the GDP per capita in China. These supporting measures cannot reduce the discrimination in the workplace, and Chinese birth rates continue to decline (unlike in the United States, where the pandemic caused a mini baby boom).

Gender blind

Over the past year, “The Great Resignation” has been replaced by other buzzwords: “The Great Return” (labor participation began to inch towards pre-pandemic levels), “The Great Reshuffle” (workers changed existing jobs), and “The Quiet Quitting” (a decline in workplace engagement). Nonetheless, it remains important to understanding employment in the United States and around the world—pandemic burnout, “tight labor market,” alleged worker’s empowerment and demands for greater flexibility and higher wages, lackluster productivity, and even labor unrest.

Far from painting a picture of worker empowerment, the data shows that “The Great Resignation,” both in China and the US, has particularly affected women working in lower-salaried jobs. Much like the global financial crisis, media coverage of “The Great Resignation” has focused on professional classes and interpreted the phenomenon of job quitting as a matter of individual choice and advancement. But the portrayal of workers as suddenly in the driver’s seat of the economy has indirectly shaped conversations around the labor market and its implications for recovery and inflation.

Gender-blind interpretations of recent labor patterns have obscured how resignations have been concentrated in high-contact low-wage sectors, with predominantly female and often immigrant and/or minority labor force. Rather than a matter of choice or work-life balance, evidence suggests that women and minorities were pushed out of the labor market, having struggled under the pressures of job instability, health care risks, caregiving demands, and pandemic burnout. The combined effects of the pandemic, inflation, and the wide-ranging ripple effects of the war in Ukraine (energy and food crises) paint a grim picture for women in the labor markets and for women’s rights more broadly. These findings highlight the urgent need for policies informed by disaggregated data and attentive to gender and class dynamics in the labor markets.

The primary source of data on job quits in the US is the Bureau of Labor Statistics Jobs and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS).

↩

Filed Under