For the past two centuries in Britain, the financial markets of US and many other high income countries have been venues in which the government provides a relatively safe investment opportunity—government bonds. At the same time, private investors seeking higher returns can invest in privately issued stocks and bonds, thereby bearing the risk of financing productive and innovative activities.

Given this division, the recent debate over the “derisking” of investment opportunities is puzzling. The concept originally arose in the context of financing activities to address climate change in low- or middle-income countries (LMICs) that have limited capacity to issue safe debt. It has since been expanded to include the activities of high-income countries, which use subsidies to induce private sector investment in green technologies, often without accompanying taxes and disincentives for brown industries.1 Most recently, there have been calls for distinguishing between the derisking of financial investors and the provision of subsidies to industrial operations.2 This essay focuses on the derisking of financial investment.

The notion of derisking finance is oxymoronic—private sector investment in private sector assets is inherently intended to bear risk. In what follows, I examine the origins and evolution of derisking in the light of recent transformations in financial markets, and argue that better policy options are nearly always on the table. In LMICs, why should the government’s limited resources be transferred to a select group of private investors, rather than public debt creation or direct subsidies? In high income countries, governments can subsidize green energy investment at the level of the enterprise undertaking the activity rather than investment returns. Investors already have a “safe” option. It is not in the government’s interest to compete against itself by creating alternative “safe” assets for investors.

The private sector and the state

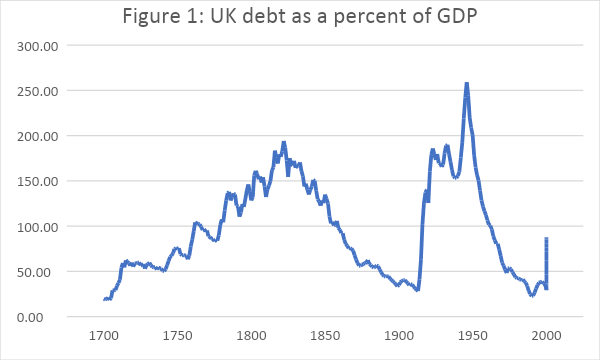

In the eighteenth century Britain became the most dynamic of the European imperial powers, backed by an exceptional capacity to raise funds through debt issuance.3 By 1800, Britain had an abundance of state capacity due to a strong administrative state that effectively collected taxes, actively promoted commerce to grow that tax base, and had a remarkably successful machinery for issuing debt and raising funds from a private sector that was operating in a robust domestic economy anchored by the Bank of England (see Figure 1).

Britain at the end of the eighteenth century presents us with an example of a state whose capacity to raise funds on debt markets rests on a delicate balance between the private and the public sectors. In this model, state capacity relies on the state’s ability to exploit private risk-bearing capacity.

The principal instrument used by Britain to borrow on a long-term basis in the second half of the eighteenth century was the consol. Consols were perpetual bonds on which the state had no obligation to repay the principal of the debt. For this reason, they were fully funded when the state dedicated a tax to paying the interest that the bond bore (which was a common practice at the time). However, consols were a form of callable debt, which gave the government the right to redeem them. Thus, Britain could issue relatively high interest rate debt during a war—say, 5 percent. Once the war ended and interest rates had fallen, Britain would offer a debt conversion to say, 3 percent to those who would accept, while paying off in full those who rejected the offer. In short, Britain’s long term debt burden was carefully designed to ensure that the private sector debt investor bore both the credit risk of the British state and interest rate or reinvestment risk.

Britain also relied on private risk bearing capacity in short-term government debt markets. Short-term debt typically took the form of either Exchequer Bills or bills issued to fund the various arms of the military. In practice, these were not redeemed until the government chose to do so. As a result, bills that were nominally supposed to be paid within a year could remain outstanding for two years or more. Which is to say that the private sector bore both the credit risk of the sovereign and liquidity risk. This was one of the reasons that the private sector short-term debt comprising inland bills was considered, despite greater credit risk, to be a safer investment than short-term government debt—it was almost always paid off on time and there were clear legal remedies when it was not.5

The British case suggests that an important foundation of state capacity lies in transferring risks that the state is ill-suited to carry—such as the timing of when debt will be paid—to the private sector. In the modern era with well-established and deep markets for sovereign debt, this form of state capacity is managed by rolling over the issues of debt, but the effect is the same.

In short, the British government did not bear risk for the private sector in the eighteenth century. As late as the 1890 Barings Crisis, the Chancellor of the Exchequer reacted very negatively to the Bank of England’s proposal that the government should bear any measure of private risk.6 Broader consideration, however, reveals there were two ways that the British government actively redistributed private sector risk. First, Parliamentary charters were granted to companies in order to allow them to raise funds on a limited liability basis. This was a way to ensure that private risk was transferred in the event of a bankruptcy because any losses would fall on the creditors of the firm and not on the owners of the company. Second, the Bank of England—which even in the eighteenth century is best described as a public-private hybrid institution—both guaranteed the convertibility of the paper currency into gold and provided liquidity on demand to those commercial bills that met the criteria it set forth for “safe assets” (or “prime” bills).

In the heyday of British state capacity and economic growth, then, the private sector derisked the state and not vice versa. A somewhat more complicated relationship held, however, at the core of the money market, where the central bank anchored liquidity in the banking system by providing extremely limited derisking services to a narrowly defined set of very short-term private sector instruments.

Over the course of the nineteenth century, stock and bond markets developed, opening many more options for private investors. By the twentieth century both the US and UK governments were issuing debt for a specified term of years, without a provision for calling the debt at an earlier date, as is the norm today. Thus, we no longer imagine investors as bearing liquidity or interest rate risk on behalf of the government when they invest in Treasuries issued by the US or Gilts issued by the UK. Instead, we think of them as investing in safe assets.7

Emergence of the derisking state

From its origins in the early nineteenth century through the first three-quarters of the twentieth century, the British government left the organization of stock and bond markets to the private sector, which from the start separated dealing activities from brokering activities and from commercial banking activities. By contrast, in the US brokering, dealing, and commercial banking activities were allowed to be combined until the 1930s, when Congress deemed this mixture to have played a role in the 1929 boom and bust on the stock market,8 and in the Glass-Steagall Act legally separated broker-dealers from commercial banks.

This structure ensured that, in the 1940s through the 1960s, important firewalls were in place preventing central bank derisking from flowing into the support of private sector capital markets, even as money markets were supported in Britain by the Bank of England and the US starting in 1913 by the Federal Reserve. This isolation of capital markets from derisking began to change in the 1970s.

With the collapse of Bretton Woods and the shift to floating exchange rates between high-income countries, the US began to support the dollar internationally by ensuring that no American banks active in international markets would be allowed to default on these obligations. This policy is now known as “too-big-to-fail.” The first bank rescued for this purpose was Franklin National Bank in 1974.9

This policy of government backstopping for all internationally active US banks ensured that they had abundant funding, which pushed them to find outlets for these funds. This dynamic played an important role in the growth of syndicated loans to low-income countries that culminated in the less-developed-country debt crisis in 1982. From 1983 syndicated loans were used by these banks to finance leveraged buyouts (LBOs), and indeed the buyout boom would not have been possible in the absence of this funding in the form of “leveraged loans” from too-big-to-fail banks.10

Not only did bank funding of capital market activities make a comeback in the 1980s, but the too-big-to-fail banks that were explicitly supported by a government backstop financed a massive increase in the debt carried by the US corporate sector. To understand this one must understand what a leveraged buyout is—the purchase of all of the shares of a company that is traded on the stock market and is paid for by borrowing about 90 percent of the purchase price with the buyer/owner putting up only about 10 percent of the price. The LBO is exceptional and controversial because the purchased company owes the debt, not the buyer. Effectively, banks were picking winners in the form of buyout firms who got to own and control some of the biggest US companies in exchange for granting to the banks a massive debt claim, typically secured by the company’s assets.

The LBOs of the 1980s were rationalized by the “free market” rhetoric of the Reagan administration. When Fed Chairman Paul Volcker sought to constrain the LBO market, the Reagan administration publicly denounced his “interference in the marketplace.”11 Less than a year later, Volcker was replaced by Alan Greenspan.

By the 1990s, uproar over the distortionary effect of leveraged buyouts on the US corporate environment had driven the buyout industry underground, focusing on privately traded companies.12 This uproar also drove the rebranding of “leveraged buyout firms” to “private equity.”13 The too-big-to-fail banks, however, found leveraged loans to be a great source of both fee and interest payments, which led them to continue to finance these transactions, thereby allowing the repeated resale of target companies from one buyout firm to another, or even from one fund to another fund managed by the same firm.

By 2000, debt-financed buyouts had become normalized, as were the high yield debt and leveraged loans that financed them. Thus, the return of the buyout was uncontroversial in the boom years from 2005–07. Just as the mortgage boom was supported by an investment instrument, called a collateralized debt obligation (CDOs), the leveraged loan boom was supported by collateralized loan obligations (CLOs). Just prior to the 2008 crisis there was a massive increase in the debt load of US companies, which was moreover scheduled to mature, or in other words to require payment in full, between 2012 and 2014. In 2009 the financial press was full of articles about the “wall of debt” that was looming because of the buyout boom from 2005–07.

By this time the buyout-firm-owned companies were worth between 5 and 10 percent of total US stock market capitalization. As a result, the buyout firms owned a significant—and the most heavily indebted—portion of the US corporate sector. After 2008, many of these companies were headed towards bankruptcy.

Buyout firms had successfully put the Federal Reserve in a box: if the Fed had normalized interest rates in 2011, a wave of corporate bankruptcies would have resulted. The interests of the buyout firms, then, were conflated with the interests of the real economy. As a result, the Fed kept interest rates low just long enough for the buyout firms to refinance their debt. While there is no question that the Federal Reserve’s goal was to support the real economy, the Fed’s post-2008 monetary policy was effectively a massive bailout of the buyout fund business model.14

Since 2008, central bank protection of the value of leveraged loans and high-yield debt has become normalized. In 2020, the Fed accepted CLOs as collateral and purchased exchange-traded funds that held only high-yield debt. Both of these policies demonstrated explicit government support for the buyout firms.

Finally, in 2023, Silicon Valley Bank’s (SVB) uninsured deposits, amounting to $165 billion, were paid in full, even as the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) regularly imposes losses on uninsured depositors. What made SVB special? Its depositors weren’t just companies that had been funded by buyout firms, but firms whose failure could trigger broader disruptions in the US economy.

“Private” equity

When banks are framed as the drivers of “creative destruction” and growth,15 they are also understood as sources of economic distortion. In particular, those parts of the economy that receive bank funding grow. Any company that can reliably roll over bank funding from one year to the next is protected from failure, whether or not its underlying business model is sound.

Thus, both “private” equity funds and private-equity-owned companies grew not because of market forces, but because the too-big-to-fail banks chose to direct their funding to them. From the start so-called “private” equity was an indirect beneficiary of the massive and distorting subsidies granted to too-big-to-fail banks.

The continued growth of leveraged lending—which dropped by only 10 percent from 2008 to 2010 and increased thereafter—indicates that the so-called “private” equity industry has been protected from failure by ongoing bank lending, independent of whether or not the underlying business model is sound.

What does government subsidizing of “private” equity mean for the derisking debate? Expansive government guarantees of too-big-to-fail bank debt, from the 1970s onward, led to the growth of so-called “private” equity. They have now been extended to support the value of leveraged loans and high-yield debt. As a result, the US government effectively transforms a wide range of private sector assets into “safe” assets. In this environment, “private” equity funds do not expect to be asked to bear risk. Instead, they seek guaranteed returns like the ones already available to them. This use of the government balance sheet directs public wealth to select private individuals. Seen from this perspective, the demand for the derisking of private debt reflects financial markets that have been distorted by government subsidies, protecting select members of the private sector from losses for half a century.

The value that private investors can contribute to the economy is their capacity for bearing risk. If they don’t want to bear risk, they should be directed to invest in government-issued bonds. When the government instead chooses to give them a guarantee on their debt, it interferes with their provision of the only service that they can provide to the real economy—risk-bearing.

Instead of using the government balance sheet to transform privately owned assets into “safe” debt, the government should be putting the funds to public use directly, by raising public debt and spending it in the public interest. Daniela Gabor points out that government subsidies at the operating level are insufficient in this environment. “Private” equity immediately organizes to oligopolize the relevant industries in order to capture the subsidies while at the same time interfering with the competitive forces that would drive prices down16

Refusing to derisk private investment is therefore just a preliminary step. The vast subsidies that are already being given to “private” equity also need to be withdrawn. The Stop Wall Street Looting Act proposed in 2019 would be a good follow up, imposing liability on the general partners of “private” equity funds for the debt they created. Separating too-big-to-fail banks entirely from the finance of so-called “private” equity transactions is also important, and normalization of Federal Reserve interest rate policy for a period of at least five years would do the rest of the work. The result would be a vast number of bankruptcies of highly indebted companies and huge losses for “private” equity investors.

Too-big-to-fail-banks will end up owning most of these companies, and they will be unable to engineer exits from their situation via new “private” equity purchases. This necessitates the creation of a new reconstruction finance corporation that deals with bank failures, alongside a government program supporting the purchase of each corporate carcass out of bankruptcy by a cooperative of workers with an interest in keeping it running. Support is also likely to be needed for pension funds that bear heavy losses from the fallout.

Just as high income countries need to withdraw their subsidies to “private” equity, LMIC should avoid creating such subsidies by derisking investments. The limited resources of these countries need to be carefully directed to support the public good, not private investors. Though the path ahead is difficult, government guarantees already create a profound distortion in our modern financial structure. These distortions need to be eliminated, not extended through derisking.

Daniela Gabor. “The (European) de-risking state.” Stato e mercato 1. (2023): pp. 53-84; Daniela Gabor and Benjamin Braun. “Green macro-financial regimes.” 2023. Available at https://benjaminbraun.org/research/green-macrofinance/green-regimes.

↩JW Mason. “Varieties of Industrial Policy.” Slackwire blog. 16 June 2023. Available at: https://jwmason.org/slackwire/varieties-of-industrial-policy/

↩Hamish Scott. The Seven Years War and Europe’s Ancien Régime. War in History 18, volume 4 (2011): 419–455; Daniel Baugh. The global Seven Years War, 1754-1763 : Britain and France in a great power contest. (Pearson, 2011).

↩Thomas, R and Dimsdale, N. “A Millennium of UK Data”, Bank of England OBRA dataset, 2017. https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/statistics/research-datasets/a-millennium-of-macroeconomic-data-for-the-uk.xlsx

↩The Treasury Bill was first issued in 1877, and was modeled on commercial bills in order to improve its liquidity . See Richard Roberts, The Bank of England and the City in Richard Roberts & David Kynaston ed. The Bank of England: Money, Power, and Influence 1694 – 1994. (1995): 155.

↩Sissoko, Carolyn. How to stabilize the banking system: Lessons from the pre-1914 London money market. Financial History Review 23, Volume 1(2016); Sissoko, Carolyn. “Transferability of financial claims” conference draft. “Law in Finance” workshop. Frankfurt 17 Feb 2023.

↩Of course, the investors still bear interest rate risk in the sense that the value of the bond will change along with market interest rates. Because the debt is typically not callable, the government cannot however take advantage of favorable interest rate changes in modern times.

↩Senate Banking Act Report, Senate Report No. 73–77, 1933.

↩Sissoko, Carolyn. “‘Private’ equity is a misnomer: government support has been driving the restructuring of US corporate structure and the transfer of wealth to buyout firms over the past 40 years.” SSRN working paper (2023).

↩Sissoko, Carolyn. “‘Private’ equity is a misnomer: government support has been driving the restructuring of US corporate structure and the transfer of wealth to buyout firms over the past 40 years.” SSRN working paper (2023).

↩Kilborn, Peter. “The New Clash with Volcker.” New York Times. Dec. 26 1985; Johnston, Oswald. “Fed OKs Rule to Restrict Use of ‘Junk Bonds’ : 3-2 Vote Goes Against Administration’s Stand.” Los Angeles Times. Jan. 9 1986.

↩Sissoko, Carolyn. “‘Private’ equity is a misnomer: government support has been driving the restructuring of US corporate structure and the transfer of wealth to buyout firms over the past 40 years.” SSRN working paper (2023); Kaplan & Stromberg. “Leveraged Buyouts and Private Equity.” JEP 23 (2009): pp. 121-46.

↩Economist. ”Barbarians at the gate 2.0.” The Economist. Oct 28 2008; Kaplan & Stromberg. “Leveraged Buyouts and Private Equity.” JEP 23 (2009): pp. 121-46.

↩Neroli Austin & Ludovic Phalippou, “Decomposing value gains – The case of the best leveraged buy-out ever.” Journal of Corporate Finance 81 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2022.102317.

↩Smith 1776, Schumpeter 1939

↩Lee Harris. “Private Equity Intensifies Rollups of HVAC Installers.” The American Prospect. October 16, 2023.

↩

Filed Under