Ten years ago, the current predicament of central bankers would seem unthinkable: to what extent should they contribute to society’s response to climate change? As the impacts of climate change have escalated, most central banks have begun to appreciate the wide-ranging economic and financial consequences relevant to their work. These include the economic damages from heat waves, storms, floods, and droughts, as well as rising sea levels, species extinction, and other environmental shifts. These physical impacts also set the stage for a disruptive societal transformation, which will have consequences for central banks’ ability to maintain monetary and financial stability. How central banks should respond to these new challenges remains hotly contested. What is the appropriate role for institutions with unrivaled power to shift the financial conditions that are critical for a response to climate change, and a complex institutional structure that grants most political independence?

On each side of the Atlantic, the European Central Bank (ECB) and the Federal Reserve (Fed) have come up with very different answers to this question, as we explore in a new working paper. In a recent speech Frank Elderson, ECB Executive Board member, delivered a call to action: “No transition, or a transition that comes too late, would be the greatest injustice of all. Delay is no solution. Delay is expensive. Delay is disastrous…We can’t allow ourselves to give up. We don’t want to give up. And we won’t give up.” Fed officials, on the other hand, were years later in considering climate change and have had a more conservative approach to their task. Speaking recently, Fed Chair Jerome Powell made the bank’s view clear: “We are not, and will not be, a climate policymaker.” On the international stage, several Eurosystem central banks were among the founding members of the new Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS), a coalition for central banks and supervisors with an interest in climate and environmental issues that has been highly influential in building and disseminating technical expertise and resources for central banks looking to address these topics. The Fed, on the other hand, abstained from joining until the end of 2020, when there were already eighty-three other members.

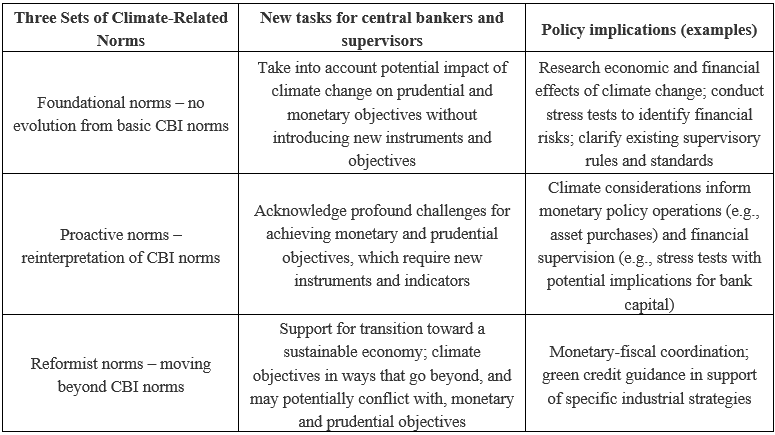

This Fed–ECB divergence is particularly remarkable because of the otherwise dramatic convergence between central banks over the course of the past decades. Since the 1970s, central banks in the West have aligned around three key policy norms. First, that they should focus narrowly on price stability targets via managing interest rates. Second, that they should focus supervision on preventing excessive risk taking. And third, that central banks—independently from political influence—would avoid interfering in credit allocation or industrial policy. Both the ECB and the Fed have centered their climate strategies around risk management through tools like supervisory expectations and climate scenario analysis (or “stress tests”). However, while the Fed has adhered strictly to foundational climate policy norms, unwilling to step in any direction that might be perceived as actively influencing the relative cost or availability of credit, the ECB has instead pursued a proactive reinterpretation of what kinds of instruments and intermediate objectives are permissible to achieve its tasks (see Table 1). This has included the ambition to “gradually decarbonize” the ECB’s corporate bond portfolio, limit the share of high-carbon assets allowed to be pledged as collateral, and grading the quality of bank climate-risk management in determining Pillar 2 capital requirements. These policies are notable because they each have the potential to result in material shifts in the cost of credit for green and carbon-intensive activities.1 In contrast, Fed chair Jermone Powell has said that he “would be very reluctant to see us move in that direction, picking one area as creditworthy and another not.” In our paper, we ask the question: what explains the new climate divergence?

Table 1: Three categories of climate-related norms

Central banks, domestically and internationally

To understand how central banks act in a given policy area, it’s important to understand their roles both as domestic and international actors. Within the above mentioned policy norms, central banks are insulated from direct political control, and are primarily directed by their legislated mandates. However, despite approaches in the central banking literature that have traditionally accepted these arrangements at face value, the reality is far more complex. Central bank mandates are often vague and include multiple objectives. They cannot speak explicitly to the vast array of circumstances modern central banks may find themselves dealing with, nor tell central banks which trade-offs to make in dealing with those circumstances. At the same time, central banks are subject to legislative oversight and their leaders are appointed by elected officials. As Joseph Stiglitz puts it, “There is no such thing as truly independent institutions. All public institutions are accountable, and the only question is to whom.” This was on full display in the wake of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, when the Fed had its autonomy to conduct emergency lending programs reined in as part of the Dodd Frank reforms. It was an example of the ways in which domestic political context shapes how central banks undertake their mandated objectives and respond to new policy problems.

At the same time, central banks navigate uncertainty by developing norms collectively in transnational governance networks. Despite the fact that central banks operate like delegated agencies domestically, with a narrowly defined basis for legitimacy tied to their political authorities, they are also independently active in processes of global diplomacy, with substantial latitude to engage in agenda-setting in new areas of policy. Central banks regularly cooperate on economic policy, implement global financial legal frameworks, and routinely lend each other billions of dollars. Financial globalization has also created a practical need for international coordination and standardization. The main site for this is the Swiss Bank for International Settlements, in particular its Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, though more recently institutions like the NGFS can be counted among these. Through such networks, central banks develop a shared “logic of appropriateness”2 about both the kinds of problems that they should address and technical knowledge about how to address them.

In our paper, we introduce a dynamic norm formation framework to describe the complex interactions over time between central banks’ domestic and international roles that shape central bank processes and narratives. We demonstrate that a favorable domestic political context around climate change set the stage for early action at the ECB, while domestic polarization initially prevented the Fed from addressing climate change. This changed as climate policy norms gained momentum among central banks through international forums like the NGFS.

Channels of influence

In Europe, action on climate change, both at the national central banks of the Eurosystem and at the ECB, has come in the context of broad domestic support for such measures. Crucially, central bankers were pushed forward both by legislative initiatives and by activist think tanks and NGOs that encouraged them to examine how climate change impacted their agendas. For example, the earliest articulation of foundational climate norms occurred outside the central banking community, with a 2011 report by NGO Carbon Tracker titled “Unburnable Carbon: Are the world’s financial markets carrying a carbon bubble?” European central banks also received pressure from government officials; the July 2015 Climate and Transition Law in France requested that the Banque de France produce a report on climate risk and climate stress tests. From 2016 onwards, the ECB came under pressure from these same actors to consider climate impact not only in supervision of risk, but also in monetary policy programs. While then-President Mario Draghi and other Governing Council members initially rejected these proposals, domestic politics rendered such a position difficult to maintain. In December 2019, the member states had agreed on the project of a European Green Deal and legally binding climate objectives set out in a European Climate Law. They had also appointed a new ECB president, Christine Lagarde, and several new board members, who initiated a review of the ECB’s monetary policy strategy that examined how to design instruments in light of climate change. These elements prompted the ECB, in turn, to increasingly move toward a more proactive approach.

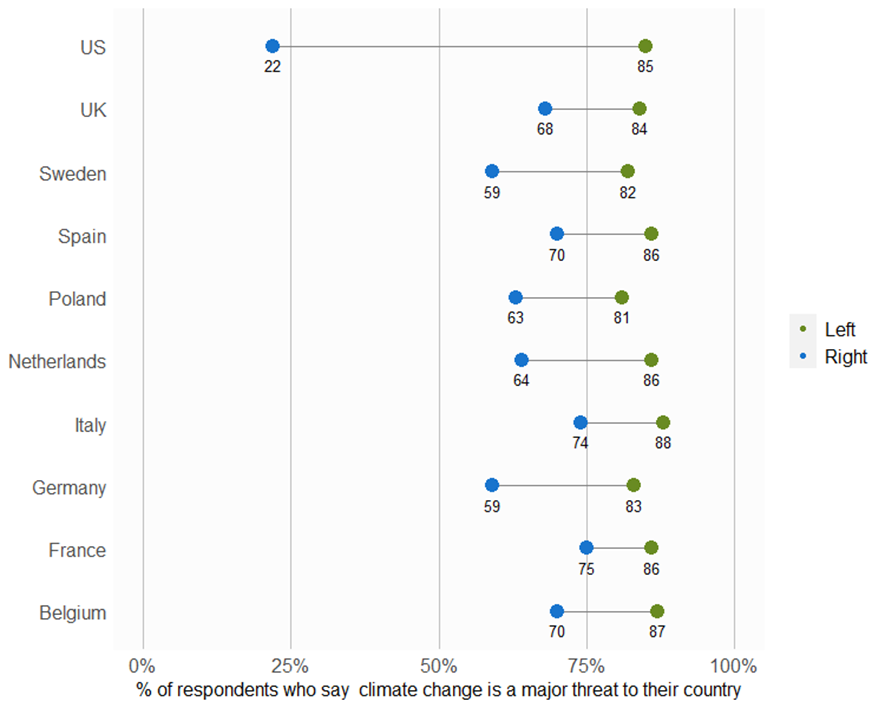

In the US, on the other hand, there was near silence from the kind of domestic actors that turned out to be crucial in the European context. For example, the abovementioned Carbon Tracker report was widely read in the United States, but it did not translate into pressure on supervisors. Bill McKibben, a prominent American environmentalist, was key in amplifying this report in the US. However, he translated it into a campaign for college students to push their universities to divest from fossil fuels. The Fed also faced a highly polarized political environment on climate issues (Figure 2), even under the Obama administration.3 While these dynamics were already present ahead of Trump’s 2016 election, this development decisively froze the agenda. With the withdrawal of the US from the Paris Agreement in 2017, along with hostile domestic climate politics, there was little basis for the Fed to act.

Figure 1: Public opinion on climate change from those who identify with the political left vs right, 2022

However, growing attention to climate change on the international stage became difficult to ignore. Though the election of President Biden at the end of 2020 substantially eased the domestic context, the Fed had, in fact, begun to devote attention to climate change at the beginning of 2019, while Trump was still in office. As Powell described in 2020, “…we are, you know, very actively, in the early stages of this, getting up to speed, working with our central bank colleagues and other colleagues around the world to try to think about how this can be part of our framework. And we’re watching what other—what other countries are doing.” Nonetheless, the Fed has remained conservative and continues to face a highly polarized domestic political context.

This is clear when examining the influence of the fossil fuel lobby in Congress.4 In 2022, for example, Sarah Bloom Raskin withdrew her nomination to the Federal Reserve Board over Congressional climate objections, which drew on her earlier comment that regulators should “ask themselves how their existing instruments can be used to incentivize a rapid, orderly, and just transition away from high-emission and biodiversity-destroying investments.” Senator Joe Manchin (D-West Virginia), in opposing her nomination, stated that Raskin had “failed to satisfactorily address my concerns about the critical importance of financing an all-of-the-above energy policy to meet our nation’s critical energy needs.” His political opposition has been linked to the high level of influence of the fossil fuel industry in Congress: Manchin had at that time taken more money from fossil fuel interests than any other senator.5

It is unlikely this climate divergence will disappear entirely. Polarization on climate policy is deeply ingrained in US politics and the Fed will remain dependent on its government for ongoing autonomy and legitimacy. Now that the Fed is more actively participating in international climate initiatives, both at the NGFS and at the BCBS, a new question emerges: will the Fed act as a conservative force on other central banks’ climate actions? This question is not only relevant for a body like the NGFS, which produces knowledge and sets an agenda for central banks internationally, but will be especially salient for standard setting bodies like the BCBS, where central banks will need to come to a new climate consensus.

FootnotesThese types of central bank actions are not a panacea, and still largely leave the particulars of the pace and shape of a transition to private actors. Furthermore, they are limited in scope, i.e., the ECB is currently unwinding its corporate bond portfolio.

March, James G., and Johan P. Olsen. 1998. “The Institutional Dynamics of International Political Orders.” International Organization 52 (4): 943–69.

McCright, Aaron M., Riley E. Dunlap, and Chenyang Xiao. 2014. “Increasing Influence of Party Identification on Perceived Scientific Agreement and Support for Government Action on Climate Change in the United States, 2006–12.” Weather, Climate, and Society 6 (2): 194–201.

Also see for example this and this.

Another explanation for the Fed’s divergence that has merit but is insufficient on its own is the Fed’s lack of secondary mandate to support government priorities, which the ECB possesses. However, the ECB only rediscovered its secondary mandate in 2021: in over 2,500 ECB speeches from 1997 until 2021, the secondary objective was mentioned in just 10. Furthermore, central bank mandates have historically been sufficiently elastic to accommodate new economic developments.

Filed Under