Monetary financing—the issuance of public money to support public expenditure—has in recent times become a policy taboo. The message from economists to politicians, policymakers, and society more broadly is often that any central bank support for public expenditure is likely to destroy an economy.

In 2009, the taboo stopped the European Central Bank (ECB) from buying sovereign debt in the open market, an activity that, as we will shortly see, European treaties had been explicitly drafted to allow. Newly issued public debt languished on the market. Eventually, pent up supply and panicked investors brought the very project of European integration to the brink of collapse. This was a very different scenario to what happened in the US and the UK, where, in 2008 and 2009 respectively, central banks launched enigmatic “quantitative easing” (QE) programs, which involved buying large volumes of government debt.

By 2020, the ECB had changed its tune. At the outset of the pandemic, it followed the Bank of England and the Fed, dutifully launching massive public debt purchase programs. Former ECB president Mario Draghi published an op-ed with the ominous title: “We face a war against coronavirus and must mobilize accordingly.” The model to follow was, he argued, was wartime monetary finance. When Christine Lagarde took over as president in 2019, she pointed to the role of government debt purchases in ensuring “supportive financing conditions […] for governments.”

In recent years, central bankers have taken a more conciliatory position. While conceding that central banking does at times involve outright purchases of debt, they maintain to the public that today’s quantitative easing should not be confused with monetary financing. The reason is that the objective of bond purchases is not to facilitate government spending. Indeed, orthodox central bankers and critical academics have alike sought to distinguish today’s interventions in sovereign debt markets from historical practices of monetary financing. Despite those efforts, there are few notable differences between the bond purchases of the Great Depression, the two World Wars, and the Cold War and the “unconventional” policies of 2008–2022. The main contrast lies in communications strategy.

In a recent article in the Review of International Political Economy, we propose a new macro-financial account of monetary financing to explain the historical continuity of central banking practices. As we show, central banks have almost always acted to buy debt issued by governments in a crisis. We make our case by pointing to how central banks supported treasuries in the jurisdictions that have issued the two global currencies of the post-industrial age: the United Kingdom and the United States. We show that monetary financing has always been important in helping states navigate large fluctuations in the demand for, and supply of, government debt. The ECB’s 2009 refusal to support struggling member states stands as an exception in twentieth-century central banking practice. Relying on newly disclosed archival documents, we also show that in the early ‘90s, central bankers drafted the ECB mandate to make sure the central bank could buy government debt when needed—an insight that got lost in the market-ideological enthusiasm of the late ‘90s and early 2000s.

Central banks have always acted—and always will act—as the lender of last resort to governments facing what we describe as “sovereign-financing gaps.” Wars, post-war reconstructions, financial crises, and other economic emergencies force the treasury to spend as fiscal receipts disappear, irrespective of private investor demand. The central bank, as the issuer of new public money, typically accommodates those spending programs, either by directly acquiring debt from governments or by bulk purchases in secondary markets from securities dealers. Its role is to monetize deficits until supply and demand dynamics stabilize. On this account, stabilization of sovereign financing conditions is a “feature” not a “defect” of central banking.

The most distinctive feature of sovereign finance is the demand for a continuous but irregular supply of funds which is exceptionally large relative to any other borrower, even in normal times. Sovereign financing gaps can easily exceed private creditors’ willingness to lend. In extreme circumstances, no credit is available in markets at affordable prices, for even the most solvent sovereign. When “debts are large and precarious creditors shy away,”1 the volume of debt that treasuries can sell, even at high interest rates, is limited. Monetary finance becomes necessary “because debt cannot be sold.” Wherever sovereign financing gaps arise, governments must rely on central banks.

As we document in the article, the Bank of England and the Federal Reserve have always provided support to treasuries issuing large volumes of debt at critical moments of fiscal distress (see table 1). Since the early twentieth century, monetized credit has been provided through a variety of operations, including unsecured credit lines, direct purchases of newly-issued debt, and secondary market purchases intentionally designed to create scarcity of sovereign debt instruments. Large secondary-market purchases have become particularly important in recent years, given the dominance of quantitative easing programs.

Table 1: Exceptionally large purchases of government debt

| Years | UK Bank of England | US Federal Reserve |

| Before 1933 | WW1 War Finance | WW1; Great Depression |

| 1933–1947 | 1944 WW2 War Finance; 1947 Reconstruction | 1942-1945 WW2; 1945–47 Reconstruction |

| 1947–1980 | 1949 Stabilization after currency devaluation; 1952–53 Coal industry nationalization | 1958 and 1970 outright purchases to prevent the failure of treasury re-financing programs |

| 1980–2008 | Overnight finance; Ways and Means used until 1998 | Fed guaranteed re-financing at primary auctions |

| After 2008 | Finance Crisis Bank rescue Ways and Means financing and QE Pandemic QE | Financial Crisis Large Scale Asset Purchase Programs; Pandemic Market Functioning Purchases |

Policymakers at central banks acknowledge this macro-financial function. When launching QE in the US, all members of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) emphasized that large sovereign debt purchases would be a form of debt monetization and acknowledged the political risks stemming from the taboo. However, even those who opposed purchases stressed the risk of non-clearance of auction in primary Treasury markets:

[T]here are serious questions being raised by market participants and market commentators about the government’s ability to fund new higher expected levels of Treasury issuance—that is, they may or may not, in the market’s view, be able to find buyers at market-clearing prices.2

FOMC members in favor of Treasury debt purchases did not argue with the core point that secondary market purchases would be a form of debt monetization. In fact, they contended that such monetization would be both desirable and controllable. As one argued:

I think right now we need to make sure that fiscal policy is as effective as it can be. So monetizing the debt to me is not a negative under the current situation, because it’s helping fiscal policy be effective—provided we can do it in the context of not having rising inflation expectations and not having concerns about our independence. 3

This is the background against which the dramatic history of the ECB’s monetary financing prohibition must be analyzed. It is a far more recent phenomenon than is typically thought, taking on its most radical form only in the mid-2000s.

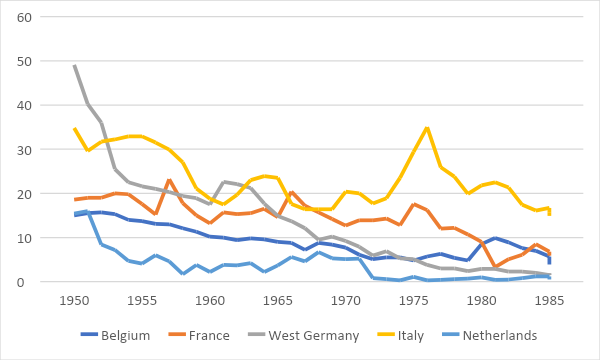

From the postwar establishment of the European Monetary Union, European central banks supported public debt markets through direct credit and open market operations (See Chart 1). This was even the case for the German Bundesbank. For example, in 1975, Germany’s central bank purchased DM7.5 billion in public securities to promote bank lending and “prevent an undesirable rise in interest rates.”4 Until well into the 1990s, it conceded that “the central bank affects the market situation, and the interest rate expectations of market players change, so that the Bundesbank may sometimes unavoidably be forced into the position of an “interest rate leader”’ to ‘smooth out erratic price movements’ and ‘ensure that the corresponding securities can trade on the stock exchange at any time, even in larger amounts.”5

Chart 1: Percentage of the central government’s debt held by western European central banks at end of year

In the 1980s, central bankers were also concerned about rising public debt, but they knew the fragility of markets too well. As the 1988 Delors Report explained:

[M]arket views about the creditworthiness of official borrowers tend to change abruptly and result in the closure of access to market financing. The constraints imposed by market forces might either be too slow and weak or too sudden and disruptive.

For this reason, the EU treaties rely on fiscal rules rather than market discipline to constrain government spending. Behind the scenes, there was no genuine attempt to prohibit monetary financing.

Reflecting this history as well as other European central bank practices, the 1992 Maastricht Treaty did not prohibit the ECB from acting as a lender of last resort to governments via secondary market interventions. It did prohibit direct transactions between central banks and national treasuries. The distinction is important because secondary market transactions are a powerful conduit for monetary support to primary debt markets.

While discussing the historically unprecedented prohibition of direct credit to governments proposed in European law, former Bank of England governor Robin Leigh-Pemberton worried that “occasionally it would be useful to undertake such operations to influence the market.” That concern was dismissed by French governor Jacques de Larosière, who pointed out that the Treaty would ‘enable the System to buy and sell marketable instruments, such as Treasury bills and other securities, in the pursuit of monetary policy. Legal options to effectively prohibit debt monetization remained unused and no prohibition on secondary market interventions to support national treasuries was entrenched.

Today, the ECB’s refusal to act as a “lender of last resort” during the turmoil of 2008-2009 is widely recognized to have brought about the Eurozone Crisis. The initial driver of the crisis dynamics were large government deficits caused by the unprecedented circumstances of the global financial disruption. Between 2008 and 2014, European governments acquired bad assets from their domestic banking sector for a value of 5.3 percent of GDP and made direct fiscal transfers for another 2.1 percent of GDP. Expenditures differed considerably, with Ireland alone spending 25 percent of its GDP on bailouts. Compounding these direct costs, the indirect costs of financial market conditions and the economic downturn were much larger. The average Eurozone debt-to-GDP level rose from 65 percent of GDP in early 2008 to 92 percent at the end of 2014. In countries such as Ireland and Spain, the public debt doubled in a two-year period. Large issuance of debt called for, at least temporary, monetization.

By the time of the Eurozone Crisis, the ECB began to see financial markets as guardians of fiscal discipline. In this new market based approach to government debt, rating downgrades, higher funding costs, and maybe even a small debt crisis, were meant to force governments to cut spending. As a board member opined, “well-functioning financial markets should reward fiscal prudence and punish unsustainable fiscal policies.”

Driven by a zeal for sound public finances, the effect of central bank actions would be the exact opposite. The ECB’s refusal to address these acute sovereign-financing-gaps led to devastating market disruptions. In the absence of decisive central bank action, financing gaps set in motion a spiral, with the falling debt sustainability of the individual member state affecting the stability of their domestic banking sector, which in turn further harmed states. Crises of public and private finance were causally linked: banks held large volumes of bonds issued by their sovereign; governments were guarantors for banks; rising sovereign yields (hence, lower value of the bonds) led to losses on bank balance sheets; thus downgrades of banks and sovereigns were mutually-reinforcing A panic ensued. Notably, although the ECB disavowed its role as lender of last resort, in practice it could not avoid it entirely. By late 2009, the ECB announced its Securities Markets Programme (SMP), which would turn out to be comparable in size to the volume of fiscal support provided by the Federal Reserve at the same time (see the table below). The SMP absorbed a total of €220 billion government debt, which amounts to twenty-two percent of the total rise of debt levels between 2008 and 2012 for the five member states included. German central bankers, nonetheless resigned in protest over the purchases, possibly unaware that their central bank had executed similar operations (on a smaller scale) only a few years earlier.

Table 2: Delayed monetary financing in the Eurozone (General government deficits as percentage of GDP)

| 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | |

| Germany | -0.12 | -3.15 | -4.38 | -0.88 | 0.01 |

| Greece | -10.18 | -15.15 | -11.29 (*) | -10.47 | -9.09 |

| Ireland | -7.02 | -13.85 | -32.06 (*) | -13.01 | -8.33 |

| Italy | -2.56 | -5.12 | -4.24 | -3.59 (*) | -2.95 |

| Portugal | -3.7 | -9.87 | -11.4 (*) | -7.66 | -6.18 |

| Spain | -4.57 | -11.28 | -9.53 | -9.74 (*) | -10.74 |

| Euro area | -2.16 | -6.24 | -6.28 | -4.24 | -3.72 |

| United Kingdom | -5.13 | -10.04 (*) | -9.23 | -7.48 | -8.13 |

| United States | -7.37 (*) | -13.13 | -12.43 | -11 | -9.22 |

Government debt purchases remain controversial today. In 2022 alone, the ECB’s Transmission Protection Mechanism and the Bank of England’s interventions in the face of the October mini-budget involve both government support and rhetorical assertions of monetary dominance. Ultimately, words are cheap. Deep functional constraints ensure the persistence of monetary financing.

Dornbusch, R and Draghi, M, ‘Introduction’ (1990) In Dornbusch, R and Draghi, M (eds), Public debt management: theory and practice. Cambridge University Press, page 6.

↩FOMC, 2009b, 80.

↩FOMC, 2009b, 95-96.

↩BuBa. (1996). The Monetary Policy of the Bundesbank. Frankfurt: Deutsche Bundesbank.

↩BuBa, 1996.

↩OECD Data – General government deficit Total, % of GDP) (2008-2012).

↩

Filed Under