Lea este artículo en español aquí.

On January 24, 2024, Argentina’s General Confederation of Labor (CGT) called for a twelve-hour general strike—the first in almost five years—just forty-five days into President Javier Milei’s term. This action was a direct response to the first measures proposed by the new administration which threatened to dismantle the pillars of workers’ rights. A week after the strike, union leader Pablo Moyano warned of future intensified actions in response to debate around the “Omnibus Law” in Congress.1 The CGT is “more united than ever” after the strike, he stated, signaling a strengthened and highly alert unionism.

Since Néstor Carlos Kirchner’s victory in 2003, Argentina has become increasingly polarized politically. Néstor Kirchner and his wife, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, governed from 2003 to 2015 with a clear bias towards workers. The ruling coalition led by the Kirchners was defeated in 2015 by Mauricio Macri, a businessman who imposed a pro-capitalist “gradualist” agenda. In 2019, Macri was defeated by a coalition led by Alberto Fernández as president and Cristina Fernández de Kirchner as vice-president, returning the government to a more pro-labor orientation. Milei’s victory continues this cycle of alternations, but with increasing volatility, as his government presents itself as a pro-capitalist “shock.”

In the early days of his term, Milei appointed former Macri government officials as ministers and advisors: Luis Caputo (former JP Morgan executive and ex-Minister of Finance), Federico Sturzenegger (former Central Bank head), Patricia Bullrich (former Minister of Security).2 And just a few days after assuming the presidency, the Oral Court of Corrientes (one of the Argentine provinces where Milei’s party won) granted parole to the repressor Horacio Losito, who had three life sentences for crimes against humanity committed during the last military dictatorship. After his inauguration on December 10, Milei emphasized the need to reduce the fiscal deficit by 5 percent of GDP, the burden of which would fall on the “state and not on the private sector.” The adjustment, then, would result from a reduction in spending rather than an increase in taxes, with public employees bearing the largest impacts.

Milei’s diagnosis is that inflation is driven by the fiscal deficit financed through currency issuance. This is a consensus view in the Argentine mainstream, and arguably supported by the IMF. For Milei, inflation is a monetary phenomenon, an excess demand created by irresponsible politicians whose only solution is a shock adjustment. But this diagnosis is deeply flawed: capacity utilization rates in Argentina barely reach 65 percent, and there is no excess demand in the economy. The most probable result of Milei’s adjustment is a deep recession.

An alternative diagnosis

Growth rates in Argentina have been low for several years. Total registered employment and economic activity have remained stagnant since 2011. Real wages have been declining since at least 2017, as chronic inflation reached 276.2 percent year-on-year by February 2024. The population living below the poverty line has reached 40 percent. Alternating governments have been unable to address these economic burdens.

Argentina’s low growth rates result from its low foreign reserves. The country needs $5 billion per month for imports but has today around just $28 billion in reserves; net reserves are negative. As a consequence, there is limited economic policy space to boost domestic demand without deepening the balance of payments crisis. Because most machinery and equipment needed for increased production in Argentina is imported, any domestic expansion that induces investment requires foreign exchange. Like other countries with an incomplete productive structure—and without access to external financing—exports must increase to finance these capital goods. When this does not happen, the central bank begins to lose international reserves. Without outside financing to provide foreign exchange, it must adjust its exchange rate. But increasing the price of foreign currency results in an increase in domestic price levels—both imported and exported products (whose price is international) become more expensive in the local currency. Given that wages are paid in local currency, workers see a decline in real purchasing power, reducing labor’s share of the national income and creating a recession. This phenomenon has long been understood and is referred to as “stop-and-go” cycles.3

In this diagnosis, high inflation is not explained by “aggregate excess demand.” Rather, rising prices and costs result from conflict between classes over the distribution of real income.4 In Argentina, there is constant pressure from the agricultural and industrial exporting sectors to depreciate the currency to reduce real production costs. But with strong labor union foundations, Argentine workers and non-exporting capitalists want to protect the domestic market—which is comprised predominately by wage earners. Workers try to raise money wages to defend their real income and living standards, raising costs at the expense of profit. Thus, inflation becomes a conflict.

In an economy with high inflation, multiple factors influence prices, among them wages, profits, basic service fees, and the exchange rate, which determines prices of imported and exported commodities. Amidst a balance of payments crisis in Argentina, wages and exchange rates are the most consequential.

The wage level depends on a subsistence basket for workers—a de facto minimum wage. But it is also determined by whether the organization of the labor market enables workers to defend or advance their standard of living in the struggle for surplus distribution. In Argentina, unions are relatively strong; they have the power to veto the government.

But so do agrarian rentiers. Represented by the Argentine Rural Society, these exporting interests have the power to delay or stop the sale of grains for export if the central bank’s reserves decline. When this happens, exporters of agricultural commodities force a depreciation of the central bank’s exchange rate, so that the amount of local currency they earn through export earnings increases. The depreciation of the nominal exchange rate allows exporting rentiers to reduce their domestic costs in terms of the export revenues. This also increases the price of imported goods—both consumer products and production-related equipment—in local currency, giving workers less purchasing power. With exported goods and their derivatives—meat, flour, electricity—all more expensive in the local currency, the cost of the basic consumption basket rises, leading to a decrease in real wages. The struggle for income distribution is fought between workers who want higher real wages and agrarian/capitalist exporters.5

Twenty years of inflation

Argentina is a commodity-exporter, and commodities—directly or indirectly—determine the basic consumption basket. Commodity prices increased dramatically in the late 2000s: in September 2006, the price of soybeans was $200 per ton. By August 2012, it had reached $622 per ton. As the price of food increased, so did the cost of the basic consumption basket.

In 2007, Néstor Kirchner reinstated collective bargaining agreements, granting unions the ability to negotiate their nominal wages. This measure was extremely important for improving the income distribution, but it also opened the door to inflation caused by distributional conflict as exporters retained the power to take back through depreciation whatever workers won through collective bargaining. Guided by a powerful fiscal policy, the economy grew steadily in the mid-2000s, and the unemployment rate dropped from 20 percent in 2003 to 7 percent in 2008.6 The incipient distributive struggle pinned workers and capitalists concerned with the internal market against exporters of agricultural and industrial products.

By 2015, this struggle produced an inflation rate in Argentina of approximately 25 percent per year. The situation worsened under Macri. When he began his term in 2015, the exchange rate was 9 pesos per dollar; four years later it was 59 pesos per dollar, a sixfold increase. Exchange-rate adjustment increased prices, and workers negotiated higher nominal wages in wage agreements.7 In 2019, the annual inflation rate had grown to over 50 percent.

In Argentina, each increase in the nominal exchange rate—or the international price of commodities—also increases the local price of commodities. This in turn raises the price of the consumption basket, leading workers to demand higher nominal wages to maintain their purchasing power, which can further raise prices. Through this mechanism, successive rounds of the exchange rate-prices-wages struggle leads to persistent and chronic inflation, and in the context of dollar scarcity, can lead to hyperinflation. Like Macri, President Alberto Fernández failed to halt this dynamic between the nominal exchange rate and wages. Inflation reached 100 percent by 2022.

Milei’s first policies

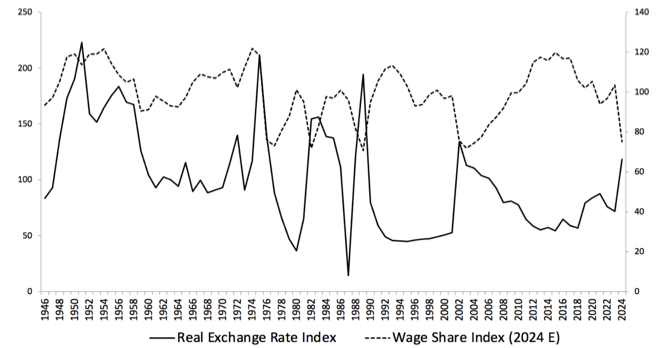

In his first significant economic policy, Javier Milei depreciated the local currency (in real and nominal terms) by almost 100 percent, shifting the official exchange rate from 400 to 800 pesos per dollar. Additionally, his government introduced a package of measures to cut public spending and cut subsidies for basic services. The substantial real depreciation of the local currency significantly impacted price levels, as demonstrated by the Consumer Price Index (CPI) monthly increases: 25.5 percent in December, 19.6 percent in January, and 13.2 percent in February. These increments cumulatively represent a compounded 70 percent price increase over the three-month period, highlighting the immediate and profound effects of the currency’s depreciation on the economy. Substantial declines in real wages and the share of wages in national income are expected, as historical trends show that real depreciations are often accompanied by reductions in real wages. Figure 1 illustrates how the workers’ share in income is essentially a mirror of the real exchange rate. Of course, the IMF supported these measures (see the IMF Managing Director’s X post below).

Figure 1: Real Exchange Rate and Wage Share in Argentina (1946 – 2024)

Figure 2: Kristalina Georgieva’s official X account

The real depreciation of the exchange rate will benefit commodity-exporters and their related industries with dollar-denominated incomes. As the wage share falls, the profit share increases. This is the case, for example, for soybean exporters and industrial exporters, who will see an improvement in their expected profitability.

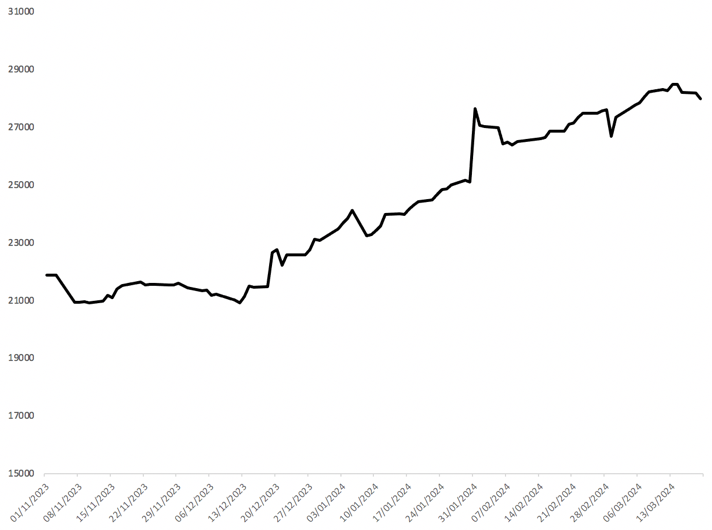

The real wage decrease, coupled with the planned reduction in government spending, will lead to a collapse in activity levels.8 With falling production, the quantity of imported inputs necessary for production will also decline. This will enable the central bank to continue the policy of accumulating international reserves, which is crucial for stabilizing the nominal exchange rate and, consequently, the price level. As seen in Figure 3, the reserve accumulation process has already begun.

Figure 3: . International Reserves (in millions of $US)

The measures taken by the Milei government will, in the short term, lead to a decline in real wages and the share of wages in income distribution, while increasing the capital share in the national income. A decrease in real wages and real public spending will lead to fall in production and employment. Consequently, the quantity of imports will decline, allowing the central bank to accumulate reserves to anchor the nominal exchange rate and attempt to curb inflation driven by the exchange rate.

The great unknown

Despite its impact on spending and wages, it is unclear how Milei’s economic policies will achieve their own objective of reducing the fiscal deficit. A reduction in public spending would decrease economic activity and domestic demand, resulting in lower private employment and investment, and in turn, a drop in public revenue.

This makes a fiscal surplus implausible. In some provinces and municipalities in Argentina, 90 percent of the budget is spent on wages—spending reductions necessitate lowering wages, with negative effects on consumption and demand. While the government can choose how much to spend at the beginning of the year, the deficit depends on revenues which are a function of activity level.

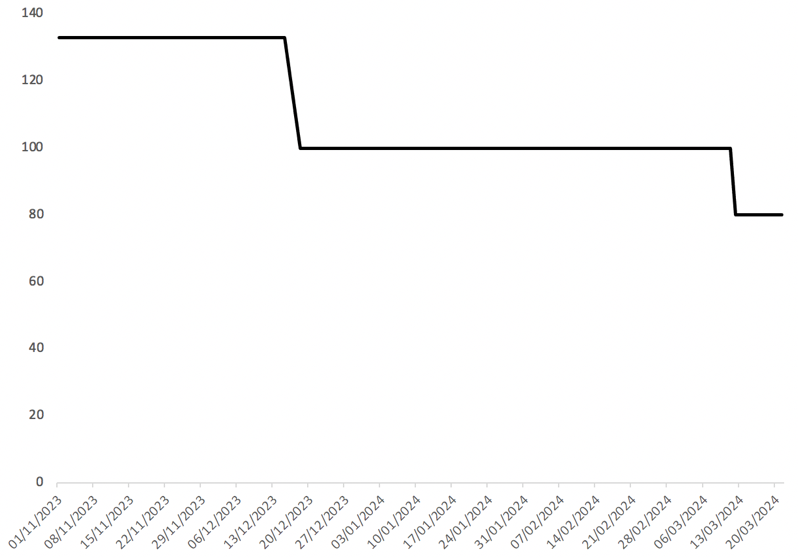

Reducing the deficit does not guarantee stabilization of the nominal exchange rate without international reserves accumulation. External factors, such as the nominal exchange rate, affect the pursuit of a fiscal surplus, and the Milei government is intent on further depreciating the peso. While the government aims to achieve a monthly crawling-peg exchange rate of 2 percent, which would allow the 80 percent nominal interest rate (see Figure 4) to offer substantial gains in dollar terms, such a shift depends on the accumulation of international reserves, which in turn, depends on the interest rate.

Figure 4: Central Banks of Argentina’s Monetary Policy Rate (Nominal Interest Rate)

After a 100 percent depreciation of the peso with an inflation rate exceeding 200 percent, participants in the foreign exchange market will likely expect further depreciation. If the expected depreciation remains high, current interest rates may not be sufficient to convince market participants. Moreover, during March, the central bank decided to reduce the Monetary Policy Rate to 80 percent. Why doesn’t the government increase interest rates? There are a few possible explanations. Several important members of Milei’s political coalition benefit from low rates relative to the expected evaluation. Alternatively, the government could be pushing the economy into hyperinflation in order to set the stage for a dollarization regime in the future.9

The distributive struggle

The main challenge of Milei’s economic agenda, however, is confronting the ongoing distributive struggle over inflation. Stabilizing the price level in Argentina requires stabilizing the nominal exchange rate through international reserves. Although Milei publicly declared a wage freeze for public employees, implementing this policy may not be as straightforward as it seems. In response to proposals targeting workers’ rights and pursuing the privatization of public enterprises, the CGT launched a resistance plan, with participation from other trade union federations. The government will struggle to manage new demands from unions for nominal wage adjustments. The teachers’ unions, for example, are in the midst of negotiations for higher wages, after dismissing the national government’s offer and planning a “National Day of Protest.”

In Argentina, the power of formal workers lies with labor unions, who negotiate with a variety of political parties and governments. Since the 1940s, the emergence of Peronism forged a symbiotic relationship between unions and the state, assigning unions a pivotal role in politics and the distribution of social benefits. The establishment of union-run healthcare systems during Onganía’s dictatorship in 1970 marked another significant milestone, solidifying unions as an essential support for workers’ welfare. Argentina’s high rate of union membership—27.7 percent— is a testament to their power.10

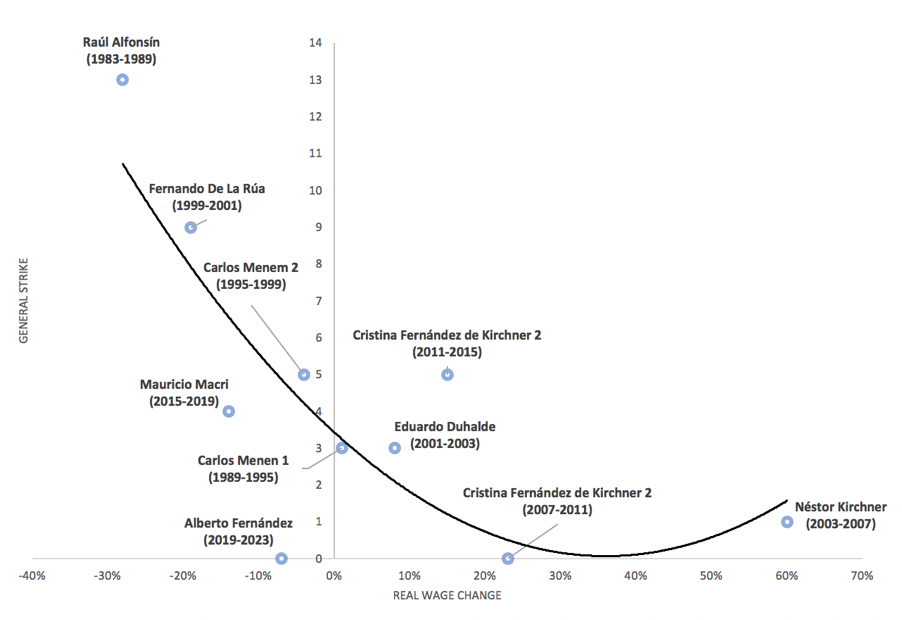

Figure 5: Relationship between real wage change and general strikes

Milei’s relationship with the unions will determine the fate of his government. In his messianic new year’s message, he foreshadowed, “If our program is obstructed by the same people who want nothing to change, we will not have the tools to prevent this crisis from turning into a social catastrophe of biblical proportions.” The ability to determine the nominal exchange rate through the central bank is the main tool at his disposal to discipline workers—beyond this lies the state’s monopoly of force. Milei could pursue hyperinflation, as he calls it, a “social catastrophe of biblical proportions”—and blame union leaders for its effects, as he has threatened in the past. Or he could choose to tactfully manage a price and wage agreement with great political flexibility, but this is at odds with the proposed agenda. If Milei’s proposals are not approved by Congress, hyperinflation could be the next agenda item.

The challenge of every Argentine government is how to accumulate international reserves in order to stabilize the nominal exchange rate while simultaneously managing political demands. The government’s proposed solution for the shortage of dollars is cutting spending and reducing real wages, but it’s unclear if this path will be politically sustainable. From 1999 to 2001, the government of Fernando De La Rúa attempted to reduce public spending in order to reach a fiscal surplus, but his term ended prematurely with the 2001 social crisis. The problem then concerns the political sustainability of the government in front of these demands. Growing poverty rates, real wage reductions and public spending cuts have the potential to generate significant social unrest.

Carlos Menem’s administration successfully implemented a similar adjustment in the 1990s after hyperinflation, but the national and international political context was very different: the Washington Consensus was at its peak, and unions participated in the negotiations. Today, the political consequences of such an adjustment are higher. Given the failure of Macri’s “gradual” approach to the fiscal adjustment, it’s unclear how a “shock” government would see different results. Historically, democratic governments that failed to negotiate with the labor unions either resorted to institutional violence against popular sectors or experienced hyperinflation. In either case, their tenures in executive power were short.

El Destape. (2024, febrero 2). ¿Paro general de la CGT? La fuerte definición de Pablo Moyano. https://www.eldestapeweb.com/economia/cgt/paro-general-de-la-cgt-la-fuerte-definicion-de-pablo-moyano-20242217590.

↩Both Sturzenegger and Bullrich were part of Fernando De la Rúa’s government (1999-2001), which ended with 39 dead and 500 injured during the “December 2001 Massacre.”

↩Braun, O., & Joy, L. (1968). A model of economic stagnation—a case study of the Argentine economy. The Economic Journal, 78 (312), 868-887.

↩Bastos, C. P. M. (2002). Price stabilization in Brazil: a classical interpretation for an indexed nominal interest rate economy. New School for Social Research. PhD Thesis; Vernengo, M. (2006). Money and inflation. A handbook of alternative monetary economics, 471-489; Vernengo, M., & Perry, N. (2018). Exchange rate depreciation, wage resistance and inflation in Argentina (1882–2009). Economic Notes: Review of Banking, Finance and Monetary Economics, 47(1), 125-144. Morlin, G. S. (2023). Inflation and conflicting claims in the open economy. Review of Political Economy, 1-29.

↩Álvarez, R. E., & Brondino, G. (2024). The limits to redistribution in small open economies: the case of Argentina. Review of Keynesian Economics, 12(1), 53-73.

↩Amico, F., & Fiorito, A. (2013). Exchange rate policy, distributive conflict and structural heterogeneity: the Argentinean and Brazilian cases. In Sraffa and the Reconstruction of Economic Theory: Volume One: Theories of Value and Distribution (pp. 284-308). London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

↩Álvarez, R. & Médici, F. (2024). An Alternative View on Inflation in Argentina in the New Millennium: The Challenges of the Current Situation. Economia Internazionale.

↩Sales in SME retail outlets recorded an annual decline of 28.5% in January (https://www.telam.com.ar/notas/202402/654319-venta-comercio-minorista-came.html). Acindar suspends 1700 employees and the metallurgical crisis deepens (https://www.pagina12.com.ar/723657-acindar-suspende-1700-empleados-y-se-agrava-la-crisis-metalu).

↩During the elections, Mr. Milei stated, “The peso is the currency issued by Argentine politicians, so it can’t be worth anything, not even excrement, because such rubbish is not even good for fertilizer.”

↩As of the most recent data from International Labour Organization, the rate of union membership in Argentina stood at 27.7 percent. This data is comparable to Canada’s 28.4 percent and significantly exceeds the United States’s rate of 10.7 percent, illustrating Argentina’s relatively high level of unionization among its workforce.

↩

Filed Under