In developed economies around the world, housing has been transformed into a major asset. It is no coincidence that rates of homeownership have precipitously increased at the same time as governments in formerly social-democratic countries have reduced basic social safety nets. As state support has been withdrawn, one’s home—now cast as a fixed asset—has taken on responsibility for providing the capital needed for reproduction, illness, and retirement. At the same time, a widespread housing shortage has taken shape in these rich economies, and almost all countries in the OECD are facing a housing affordability crisis. Canada, New Zealand, and the UK all typify this new state of affairs, but the case of Australia provides a particularly stark example of the rapid acceleration of homeownership on a national scale—and the political recalibrations that are emerging from it.

It was never inevitable that a homeowning middle class would become the bedrock of Australian politics. Emerging from World War II, trade union density was among the highest in the world and the unions themselves were increasingly militant, in part influenced by the growth of the Communist Party, whose membership included the leaders of the mining, dockworkers, metalworkers, and sea workers unions. Post-war reconstruction was led by a Labor party who sought to use planning to sustain full employment. Responding to a housing shortage exacerbated by large-scale migration programs,, the Labor government invested in new public housing projects. The Minister for Postwar Reconstruction, John Dedman articulated the government’s concern in providing “adequate and good housing for the workers.” “It is not concerned,” he went on to say, “with making workers into little capitalists.”

Robert Menzies, the Prime Minister from 1939 to 1941 and 1949 to 1966, sought to build a new center-right Liberal party as the Labor government attempted to ensure wartime controls would be maintained in the peacetime reconstruction. Terrified that economic planning would lead to the socialization of industry, he sought to build his party around the “nameless and unadvertised” middle classes, who provided “the foundation of sanity and sobriety.” “Responsibility for homes” would be the bedrock of this new political identity.

With his election in 1949, he undertook a mass house building program to increase the supply of homes. Policies like tax concessions, war service grants, home buyer grants, a sell-off of public housing, rent controls, and incentives to banks to prioritize mortgage lending at affordable rates ensured that when Menzies left office in 1966, homeownership was above 70 percent. His promotion of the “little piece of earth with a house and a garden which is ours” to national lore meant urban sprawl and suburbanization. As intended, this had dramatic effects on class formation throughout the country. By incorporating significant elements of the workforce into this property-owning middle class, Menzies created a political identity that was, as the biographer Judith Brett described, “not opposed to some other class but… to the very idea of class.” The property-owning middle class became the core constituency for the Liberal Party’s post-war dominance: it ruled from 1949 to 1983, with only a three-year interruption between 1972 and 1975.

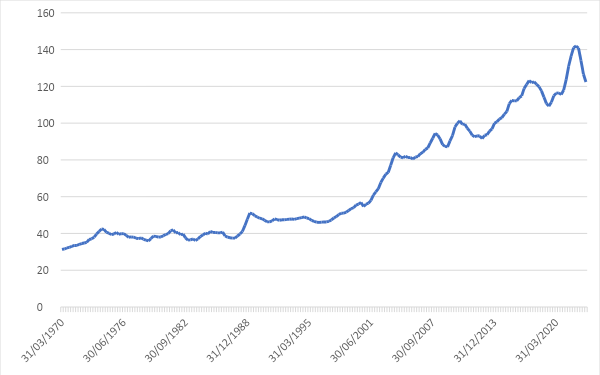

Real residential property prices in Australia, 1970-2022

When the Labor Party finally returned to power off the back of a deep recession (1981–83), it maintained the Conservatives’ commitment to homeownership. Prior to the 1983 election, Labor negotiated an “Accord” with the trade union movement, where the unions would demobilize and agree to wage suppression in exchange for an expansion of the social wage. The Accord underpinned the Labor government’s policy approach (which later served as an inspiration for Tony Blair’s re-invention of the Labour Party in Britain), as it enabled the Hawke government to step up privatizations and the deregulation of financial services, among other reforms. This in turn restimulated the housing market as foreign competition led to increased business lending. After the Basel Capital Accord of 1988, which lowered the risk weighting of home loans, Australia’s domestic banks made a concerted shift towards home-lending. An easy credit environment and lower interest rates stimulated mortgage demand amongst lower-income Australians. Supply dropped and prices shot up as a consequence.

The dilemma of salient housing politics

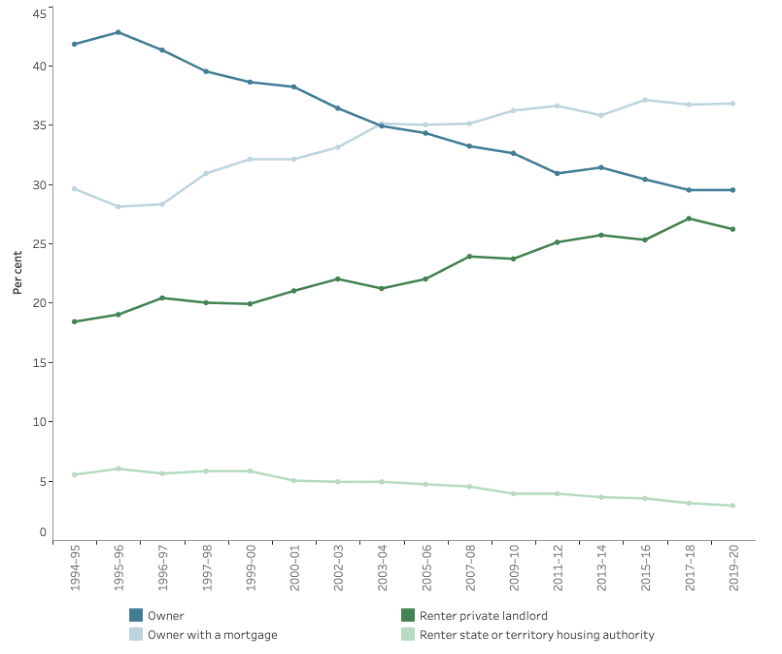

With the expansion of mortgage lending, mortgage holders have become the most politically consequential social group. A consistent finding from the Australian Election Study is that outright owner-occupiers are more likely to vote for the Liberal–National Coalition, while renters tend to vote Labor. That means that for Labor to win an election, it needs to simultaneously satisfy the interests of both renters and mortgage-holders. In practice, Labor has effectively taken renters for granted while prioritizing the preferences of homeowners. The party’s hallmark policy is a help-to-buy scheme, which enables the party to claim to help renters into homeownership, but only contributes to house price inflation and increases the value of asset values for existing homeowners.

Proportion of households by housing tenure type, 1994–1995 to 2019–2020

By 2023, more than two-thirds of young Australians have given up the dream of home ownership. The household debt to income ratio has more than doubled since 1995, now sitting at 211 percent—the fourth highest in the OECD. In the mid-1990s the average Australian household would have to devote 20.8 percent of their income towards mortgage repayments; today that figure is 45.4 percent. At present, the national average deposit for a home is $119,550; for those still renting, saving such an amount is likely to take over 8 and a half years. A survey commissioned by the pressure group Everybody’s Home found that 67 percent of Australian renters are experiencing rental stress, a standard benchmark defined by a household paying over 30 percent of its income towards housing. In this market, help-to-buy schemes are grossly insufficient to prospective buyers. House prices are simply too expensive for the mythology of homeownership to be sustained.

This is the context in which the newly elected Labor government has sought to pass the Housing Australia Future Fund (HAFF) through parliament. Australia would invest $10 billion AUD on the stock market and—should they exist—spend the proceeds (capped at $500 million per year) on building social housing—albeit an inadequate amount to the scale of the housing crisis, by all accounts.

The Greens, who hold the balance of power in the upper house, and held up the HAFF until more concessions were won, have, quite explicitly, sought to define and mobilize renters as a specific political constituency. Rather than prospective homeowners, the Greens frame renters as a group that is opposed to landlords in zero-sum terms: if rents go up, landlords win and renters lose. This better describes relations within the structure of Australia’s rental market, which is defined by a dearth of institutional investors and is dominated by landlords that typically own only one or two investment properties. As a result, close to a third of Australians, who are more likely to have lower incomes and less wealth, rent from a more affluent 20 percent that own investment properties. Yet perversely, the latter group receives greater government support. Under the existing tax structure, investors can negatively gear a rental property, which means that they receive an annual tax deduction on any losses that they incur from their investment and if they sell their property, capital gains are taxed at half the nominal rate, rather than the real rate. In making rent controls a condition of their support for HAFF, the Greens reframed the terms of debate around housing. Nevertheless, in September, the Greens ultimately passed the HAFF, after securing an additional $3 billion in direct funding for affordable housing though no meaningful support for renters.

According to the Labor party, industry groups, and much of the media, a rent freeze would scare off landlords and reduce the supply of rents. Not only is this unfounded, it is out of step with public opinion as three-quarters of voters support some form of rent control. In reflecting on the decision to back down, the Greens’ spokesperson for housing, Max Chandler-Mather, described the HAFF as just a first step, adding, “I do not think we would have won $3 billion [in total] for public and community housing, if there weren’t hundreds of people across these country knocking on doors going to rallies and building this campaign.” The Greens have identified Labor’s help-to-buy scheme and tax reform as issues through which they will once again demand support for renters in order to secure passage through parliament, while Chandler-Mather speculates that it may take “Labor [to] lose a bunch of new seats to the Greens because they ignore the one-third of this country who rents” in order for reform to occur.

Social democracy in an asset economy

Australia’s housing market is far from unique. In Britain and the countries that were once known as the “white dominions,” the financialization of housing has been widespread and renters have not only suffered, but more or less been kept out of the political equation by the leading parties. Debate and policy has followed the interests of speculators and developers. Like their sister party in Australia, Labour Parties in the UK and New Zealand discuss the problems in housing in terms of supply and demand. The solution appears simple: build more houses. Though the specifics are often lacking, and it can only be presumed that the targets will be achieved by subsidizing and incentivizing private developers.

The mobilization of renters that is being attempted by the Australian Greens is indicative of the instability, and ultimately the exhaustion, of the prevailing Social Democratic approach to housing. In siding with property developers, these parties are attempting to maintain the basic structure and social relations that exist in housing markets, where homeownership is heavily incentivized as the ideal mode of living. While there are, of course, significant supply problems in contemporary housing policy, it is impossible to sustain an arrangement in which existing homeowners retain economic security through the value of their homes while retaining affordable access for prospective buyers. As Greens’ leader Adam Bandt has emphasized, the Greens are seeking to offer “a genuine social democratic alternative.” But what is a social democratic approach to housing in the contemporary political context?

Ireland may offer some way forward. Sinn Fein’s housing spokesperson Eoin Ó Broin has endorsed a rent freeze, rejecting the standard argument that doing such would encourage private landlords to sell their properties. Party leader Mary Lou McDonald suggested that, if in power, the state would buy these properties and convert them to public housing with the intent that existing tenants would keep their lease. Alongside these changes, Sinn Fein would double the construction of housing but, significantly, mandate that more than half of these would be social housing. Ó Broin argues that investment in new housing technologies, like off-site manufacturing and assembly, would upscale housing targets.

Sinn Fein’s housing policy repositions the state as a housing provider. Rather than just subsidizing private developers, the state would play an active role in construction, by coordinating technological advancement, procurement and ending tax incentives for construction projects outside of social housing. Across high-income democracies, the costs of rents and mortgage repayments is largely unprecedented. These groups should form the basis for a new Social Democratic approach to housing, so long as parties can make tangible the purpose of a home.

Filed Under