In 2019, Florida Governor Ron DeSantis signed a bill into law that deregulated new hospital construction and unleashed a “hospital-building boom.” Some sixty-five new hospitals were planned in the three years after DeSantis signed the bill ending decades-old regulations on hospital construction called “certificate of need” (CON) laws, which could amount to as much as a 20 percent increase in total hospitals in the state.1 And it isn’t just Florida: Ohio repealed its own CON laws for hospitals in 2012. Today, Ohio is experiencing its own hospital boom. In 2019, the Cleveland Clinic planned a new facility within seven miles of two other hospitals and two other health systems. “The Columbus area seems sick with medical construction,” reports the Columbus Dispatch, “Every week, it seems, another major project gets underway.” In 2022, the largest and wealthiest hospital system in Massachusetts—Mass General Brigham—received approval for an enormous $2 billion expansion. Nationally, total private construction spending on healthcare facilities has nearly doubled in the past decade, rising from $28.9 billion in 2014 to $50.4 billion in 2023.2

As some pundits tell it, this type of “supply-side” competition-based expansion is exactly the medicine our healthcare system needs. The root cause of constrained access and rising healthcare costs, the argument goes, is public regulation giving the provider side of the market more leverage, allowing it to extract higher payments from insurers. Greater competition will lead to expanding supply, leveling the playing field between providers and insurers without altering the nature of ownership or public responsibility in the sector. “Call it supply-side economics, but for healthcare,” Matthew Yglesias wrote in Bloomberg, advising that we “focus less on the way insurance works than on expanding care to increase competition and reduce prices.” The Nikansen Center echoes the sentiment and generalizes it across those service industries at the core of American life. In healthcare, higher education and housing, this bipartisan consensus argues, supply expansion is the solution to rising costs.3

Hospital supply expansion surely is needed in many places in the United States; decades of disadvantage, discrimination, and disinvestment have left many communities—particularly those with low-income and minority populations—deprived of needed healthcare facilities and resources. The problem is that the new “supply-side” gambit won’t succeed in securing access to healthcare for these populations. Nothing in the existing marketplace ensures that new construction will go where it’s needed. All evidence suggests that it will, rather, be put in the service of gaining market share in already lucrative areas. Tampa’s new $246 million BayCare facility, in the Tampa suburb of Wesley Chapel (population 64,866), is one such example. As Kaiser Health News reports, it “doesn’t provide any health care services beyond what patients could receive at a hospital just 2 miles away,” and indeed yet another hospital is under construction a mere five-minute drive away. “The building of new hospitals and the expansion of existing hospitals,” a hospital CEO told the Cleveland Plain Dealer, is mostly “competitive strategy.” Nor has the near doubling of hospital construction expenditures over the last decade done anything to reduce hospital expenditures, which have risen 20 percent in the same period.

“Supply-side economics, but for healthcare” misdiagnoses the basic problem, which is not the performance of competition but rather the nature of financing and ownership. US hospitals are increasingly dominated by corporate behemoths and private equity firms who usher in skyrocketing prices and inequities while degrading the quality of care. Any effort to expand supply within the existing US healthcare scene will only accelerate this galloping corporate takeover, making us worse off in the process. Moreover, the nature of healthcare—a service with unique characteristics distinct from other commodities—poses profound consequences for the supply-side strategy of harnessing entrepreneurial spirits to expand provision efficiently. Unlike other services, the supply of healthcare induces its own demand, for every human body ultimately fails. Hospital beds, doctors’ hours, and machines can generally be put to some use. Nor is technological innovation likely to increase the cost efficiency or labor productivity of provision; on the contrary, as its capital base has grown, the US healthcare sector has become more—rather than less—labor intensive.

Competition in pursuit of endless market-driven growth is a quest toward a mirage. If we hope to overcome the challenges that our contemporary healthcare sector poses to improving community health, a new perspective is needed. Like the venerable services of art and education, whose rising costs were studied by the economist William Baumol more than half a century ago, the fundamental value of healthcare services (and care work more generally) is inextricably tied to the time—labor hours—that workers put into them. Healthcare services are essentially Baumolean: time is, after all, the essence of care. This poses universal challenges for any public health strategy. For if the question of how to allocate the time of our growing healthcare workforce is inseparable from that of supply, then the market-based answer of technological innovation and competition is no answer at all. Where questions of allocation persist, so too lurks the long-dormant idea of healthcare planning.

The pitfalls of quantitative supply expansion

In an influential paper published in 1959, health policy thinker Milton Roemer and his colleague reported that some 70 percent of hospital use rates could be explained by bed supply, in part based on their analysis of hospital data from Saskatchewan.4 They famously concluded that “hospital beds that are built tend to be used,” at least when populations are well insured. The idea that supply creates its own demand in healthcare came to be known as “Roemer’s Law.” What might explain this form of “provider-induced demand”? To cynics, it might seem like straightforward fraud: clinicians with time on their hands providing unnecessary care when patients have the means to pay for services (e.g. generous insurance) and don’t know better. That certainly can occur: one field-based study found that Swiss dentists with more open appointments were more likely to recommend unnecessary cavity fillings.5 But this is only a small part of the story. Doctors, after all, are in large part responsible for encouraging patients to undergo unpleasant procedures, medication regimens, and so forth that improve their health—arguably, a form of “nagged” if not “induced” demand. But additionally, spare medical resources can typically be put to some use. An entirely scrupulous primary care clinician whose clinic schedule suddenly opens up is more likely to invite patients to return for follow-up visits at shorter intervals. In other words, the schedule won’t stay open for long—and the extra care might benefit some patients. Similarly, ICU physicians (like me) responsible for triaging patients to either a bed on the regular hospital floor or to the ICU, depending on their severity of illness, are more likely to send borderline cases to intensive care when there is greater availability of open ICU beds (and vice versa). That’s not a bad thing, particularly in the context of fixed costs: the intentional use of unused supply, assuming it is at least marginally helpful (e.g. closer nursing attention in the ICU) can be rational and appropriate.

Subsequent studies have confirmed Roemer’s basic hypothesis. Multiple recent econometric analyses have found that when a shift of demand affects the use of care by one population—for instance, due to gain (or loss) of insurance coverage—the change in utilization of care by that population tends to be offset by slightly less (or more) care provided to populations whose coverage does not change.6 Economists Sherry Glied and Kai Hong, for instance, found that increases in the use of care by the non-Medicare population due to expanded eligibility for Medicaid had offsetting spillover effects on the (stably insured) Medicare population, who were provided slightly less care of little or no medical value. As they concluded, when a population has a high enough level of insurance coverage, “the aggregate quantity of health care services consumed is largely dependent on the supply side of the healthcare market.”

My research with colleagues has come to similar conclusions. We analyzed health survey microdata before and after implementation of Medicare in 1966 and the Affordable Care Act in 2014, finding little evidence for an aggregate increase in society-wide healthcare use despite a substantial expansion of insurance (i.e. of demand), with some redistribution in use towards newly insured populations. Reviewing published utilization effects of some thirteen universal coverage expansions in capitalist nations over the past century, we found generally similar trends. For instance, studies performed in the United Kingdom and Canada examining the implementation of each nation’s universal system (both of which provide free medical care) found that increases in doctor visits among those with low incomes were offset by small reductions in visits among those with the highest incomes.8

The problem of competitive supply expansion

But what if, instead of emphasizing the effects of supply expansion on aggregate supply, we were to emphasize its role in enhancing competition (and thereby reducing costs), as “supply siders” suggest? In addition to the Roemerian dynamics that would undercut potential cost-savings from such an approach, there are other reasons why efforts to gin up market competition are a fools’ errand.

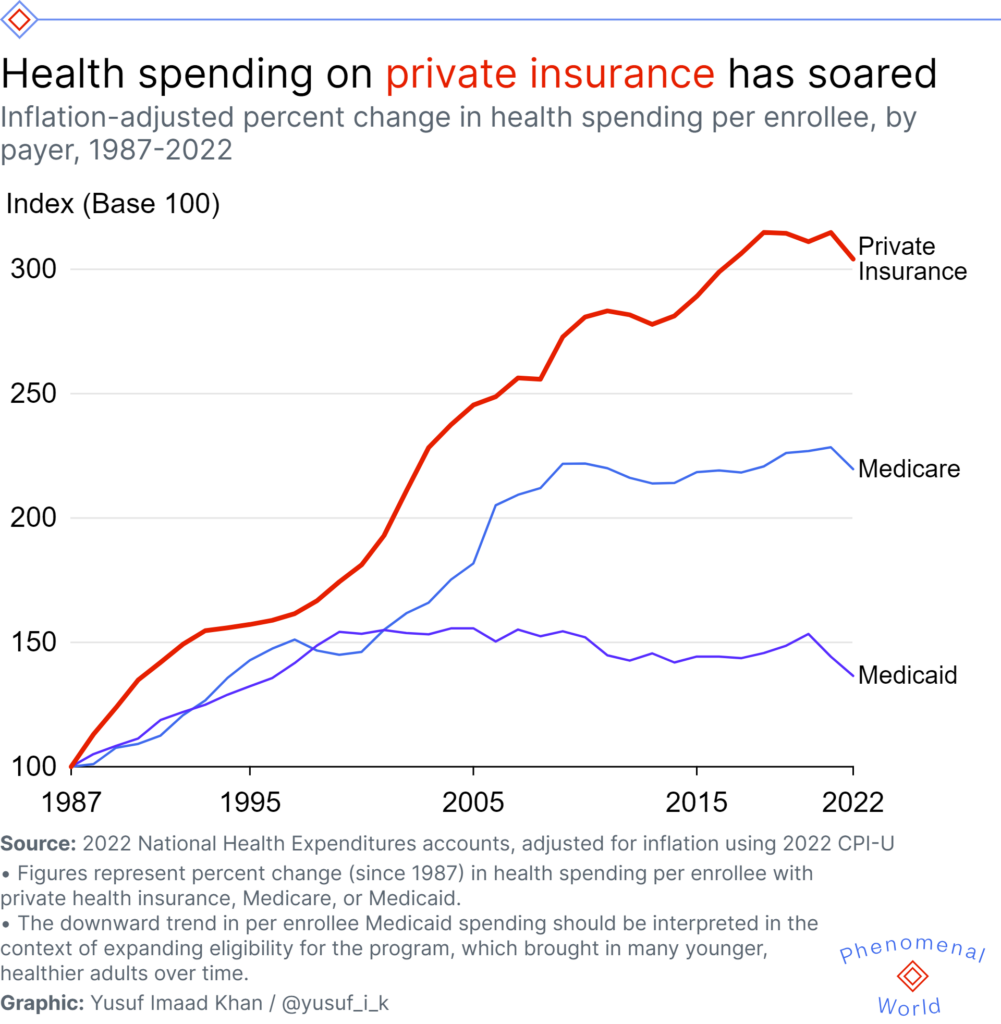

The majority of payments to hospitals in the US today are not set competitively by markets, but administratively by the government, mostly Medicare and Medicaid. Thus, any impact of greater competition would mostly be limited to those prices hospitals charge private insurers (which may in part explain the Niskanen’s and Cato’s embrace of the idea). This expensive minority of the market does drive the upward creep of system-wide costs, but it is as much through the fundamentals of expensive technology, drugs, and the very financial interests of private insurers themselves (which take a large and steady share of rising premiums for their high administrative overhead, including profits) as it is lack of provider competition. After all, the seminal 2019 study casting light on hospital payments from private insurers, published in the Quarterly Journal of Economics, found that prices at monopoly hospitals were 12 percent higher than those located in markets with four or more competing hospitals. That differential is real, but it represents a premium above the industry’s basic costs, which have risen over 200 percent (adjusted for inflation) since 1987.

It is also essential to stress that a deregulatory, market-driven approach to supply expansion will only exacerbate the uneven, unequal geographic landscape of healthcare in the US. This is already a major problem. One analysis, for instance, found that new cardiac catheterization facilities are more likely to be set up near existing facilities, rather than in places of unmet need: competition for cardiac catheterization patients is the apparent explanation for these redundancies. Meanwhile, excessive provision of cardiac services, notably cardiac stents, remains a significant problem, with supply of the specialty service (again) a likely determinant of the overall provision—and possibly overuse—of this service.9 Similarly, the robust market-driven expansion of neonatal ICU programs between 1991 and 2017 was basically uncorrelated at the regional level with either perinatal risk (a metric of community need for these programs) or of baseline differences in supply, according to another study.

But perhaps most fundamentally, the supply redundancy that real competition requires is simply not feasible or desirable in many communities, or for many health services. It is largely meaningless when it comes to emergencies: patients do not want to comparison shop on the way to the hospital when exsanguinating from a gunshot wound or struggling to breath with COVID-19 pneumonia. And for specialized surgeries like transplantations, a high patient volume is needed to maintain professional and center expertise: a particular community may only be able to sustain a single such center (if any). Some communities simply require only one hospital. And in cases where there are more than one, it’s better for healthcare workers and patients when they coordinate: as the pandemic revealed, cooperation, not competition, is the needed virtue in healthcare organization.

But redundancy is the inevitable outcome of the market-driven healthcare system in the US—as the current hospital building boom attests. The expansion of healthcare capital tends to follow operating revenues and firm profitability; in an unequal society (with inequitable health coverage), neither revenues nor profits have any necessary relationship to the underlying health needs of the community. In a recent study, colleagues and I report that the distribution of hospital capital—physical assets like land, structures, and equipment—is linked not to a community’s health needs but to its private wealth. Moreover, we find that the provision and costliness of care provided at the population level is positively correlated with hospital capital.10 With this in mind, the causes of the industry’s persistent cost creep and the inequity in its distribution of services come sharply into focus. Investment flows to well-off populations that are already well-served. In contrast, disadvantaged populations are more likely to see a withering of healthcare capital, as witnessed by stories of hospitals closing within many major US cities even while construction booms elsewhere. A recent study confirms that hospitals are far more likely to close if they are located in Black and socially-disadvantaged communities.

Far from community-wide population health needs, it is market pressures themselves that appear to be the primary driver of both hospital capital expansion and rising costs in the US market-based healthcare system. The solution to an inequitable distribution of supply—or market-driven consolidation—is not to further unfetter market forces in a fruitless effort to ramp up yet more competition: the answer, quite simply, is public planning that explicitly allocates capital resources based on community health needs and not their potential for revenue production.11

Grand illusions of a productivity fix

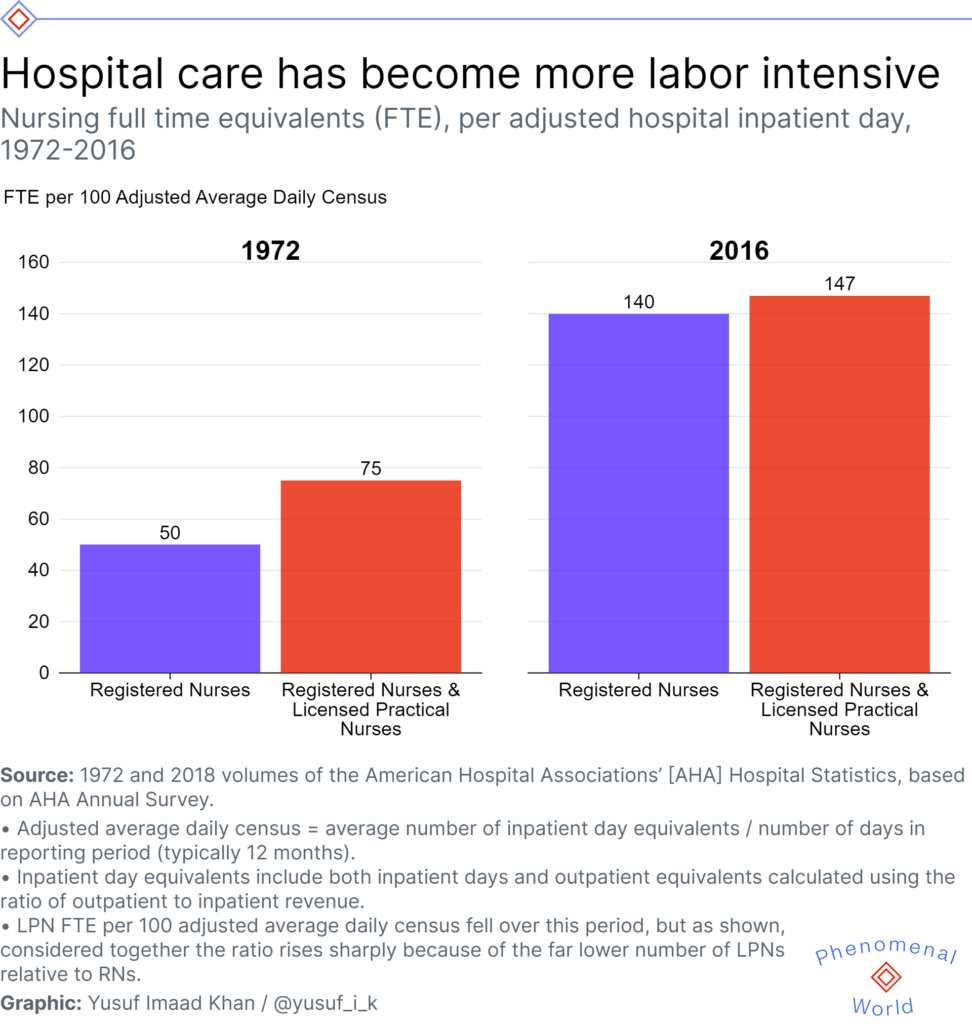

If a quantitative or competitive expansion of hospital infrastructure is unlikely to reduce society-wide aggregate hospital expenditures, there’s even less hope of a qualitative supply-side transformation in care provision via technological advance that achieves a vaunted productivity revolution. Many hope that investments in new medicines or technologies (e.g. the electronic health record, telehealth, or AI) might dramatically reduce the labor costs of providing healthcare, boosting sector productivity and improving access. However, similar to other forms of care work, the value of healthcare services is directly linked to the quantity of labor-time contained within them. Shortening the average length of a doctor visit, intuitively, renders that visit fundamentally less valuable.12 (Time pressures, no doubt, drive demand for concierge care). Similarly, the productivity of inpatient nursing for hospitalized patients can not be increased without sacrificing the quality of care—i.e. increasing nurse : patient ratios and giving patients less individualized attention. And even if it were desirable, the notion that technology will increase medical productivity is empirically unsubstantiated.13Over the past fifty years—a time of unprecedented expansion in hospital capital and medical (and information) technology—the number of full-time hospital nurse equivalents per inpatient bed day has not fallen, but actually doubled.14

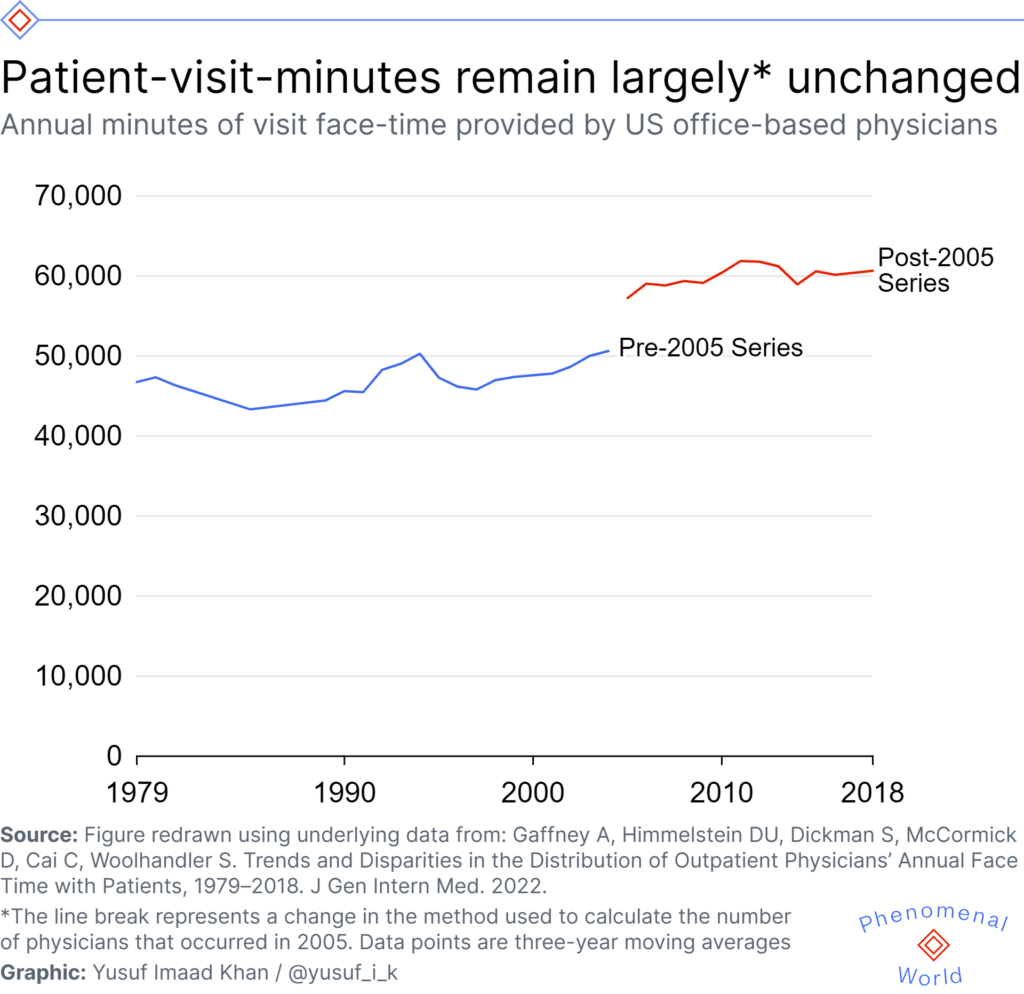

In a recent study, we similarly found that the number of patient-visit-minutes provided annually per US physician has effectively remained largely unchanged since 1979: none of the enormous technological medical changes of the past half-century increased the number of annual visit minutes doctors can provide (nor would we expect it to).

Economist William Baumol described this dynamic—and its economic consequences—some time ago, albeit without reference to the medical sector. In the 1960s, he pointed to the live performance of a string quartet as a canonical example of a service where labor productivity cannot increase. Two-hundred years ago, an hour-long quartet production required four musician labor hours—and the same is true today. (Listening to a recording or watching a live stream is, qualitatively, a different product). If we assume that pay for musicians must nevertheless be linked to economy-wide wages, as musicians exist in the broader labor market, then the labor costs to society of string-quartet productions must definitionally rise over time.

Baumol saw this proceeding towards one of two endpoints. In one scenario, where demand is elastic, the “low-productivity” sector will wither and shrink, and potentially be reduced to a luxury niche market: to some extent, this might be said to have occurred in the case of contemporary classical music. In a second scenario, where demand is less elastic or the service is publicly subsidized, “low-productivity” service sectors will encompass an ever-increasing share of the total workforce. That well describes healthcare, and many care services from education to domestic work, today.

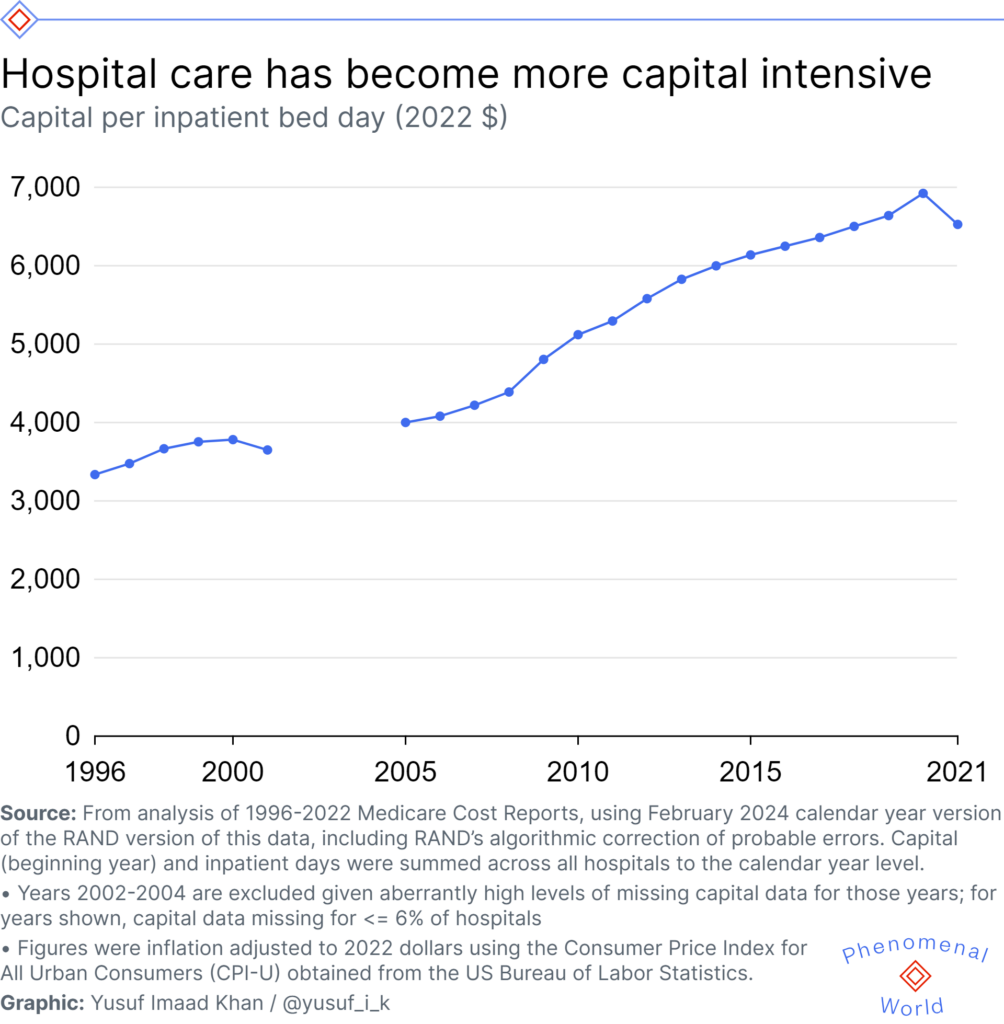

But healthcare diverges from Baumol’s canonical string quartet in some important respects that have obscured its fundamentally Baumolean characteristics and confused thinking about reform. First, there is the extent of already existing public-financing: in a recent study, colleagues and I demonstrated that the tax-financed share of total healthcare expenditures has soared over the last century, from 9 percent in 1923 to 69 percent in 2020. Second, there is the elasticity of demand: in major trauma, for instance, you pay whatever the price may be. Demand, in that clinical context, tends to be entirely inelastic. Third, healthcare, unlike the string quartet, has undergone massive technological advances in the past century, and indeed has experienced remarkable capital expansion. I estimate an approximate doubling in (inflation-adjusted) hospital capital per hospital bed day over the last twenty-five years.

Critical to the economics of healthcare is the fact that this rising capital investment has been accompanied by not just stable but rising labor intensity: the number of hospital nurses per hospital bed day, as previously noted, has risen over time, whereas the number of musicians per quartet-hour has remained exactly stable. Fifth, and finally, healthcare is undergoing an unprecedented corporate consolidation that has put it at the commanding heights of the economy. At the same time, on a more fundamental level, the similarities are perhaps more salient: an hour-long consultation with a physician or an hour of bedside nursing has always required, and will require to the end of time, precisely one hour of labor.

Now, in spite of this, it is obviously (and thankfully) true that capital expansion and technological change can vastly improve medical treatment. And admittedly, this can economize on the labor inputs needed to treat specific disease processes. Tuberculosis (TB) offers a sharp example. Before the development of anti-TB chemotherapy, vast amounts of resources were spent in maintaining and operating sanitoria for tuberculosis patients, and the workforce that cared for them. In 1946, for instance, 412 tuberculosis hospitals with 75,000 beds and 36,000 personnel were in operation, with an average daily census of some 55,000 patients.15 Today, by contrast, no such hospitals exist in the US and TB is generally treatable with some months of oral medications at home. Even without a comprehensive study, we can assume that the labor hours devoted to mitigating TB-suffering, society-wide, is vastly smaller today than it once was. TB-care is more productive.

But such disease-specific changes in medical “productivity” do not aggregate to total cost savings (or reduced labor inputs) for the nation. For one thing, it is an unfortunate fact that curable infectious diseases are something of the exception to the rule in medicine: most of the burden of illness we experience stems from chronic disease processes (and acute complications thereof) that result from aging and environmental and social conditions. For another, improving health and longevity may actually increase our lifetime healthcare needs. Technological change that vastly reduces medical labor for one illness (say, vaccination leading to smallpox eradication in the 1970s) can increase the opportunities for healthcare services if it increases the size and longevity of the population: a disease process that kills us, after all, prevents us from using healthcare services thereafter. (It is a dark commentary on the state of the healthcare discourse that such facts must be explained.) By one estimate, for instance, helping people to quit smoking will increase their healthcare costs in the long term, which, obviously, is a very good thing. We live to die another day: deferring death is (in a sense) a primary metric of success of medicine. Medical failure, in contrast, can be what actually saves money: the Covid-19 pandemic, tragically, reduced Medicare costs because it killed so many enrollees with high needs.

A unique economic principle of healthcare hence emerges from these basic realities: as a general rule, the advance of medicine will typically fail to reduce the aggregate labor-time needed to treat disease in a society, and indeed may well increase it. This may in part explain why the explosion of medical technology (and better overall health as reflected in rising life expectancy) over the last century has been accompanied by a giant increase in the share of the workforce employed in healthcare in the US, and globally. Far from “robots” (i.e. physical capital) replacing healthcare jobs, investment in these technologies seem to create them. The advent of new diagnostic tests, procedures, or therapies have not reduced the amount of time that a physician needs to interview a patient, perform a physical, examine imaging studies, review laboratory results, read past medical records, and confer with colleagues. On the contrary, integrating expanding reams of data, formulating an assessment and plan; counseling patients and families and responding thoughtfully to queries and concerns; advocating for patients or pushing back against bureaucracies created to manage capital equipment; and contemplating decisions to operate—all increase the complexity and time required for responsible medical care. As the diagnostic options widen, as the therapeutic armamentarium expands, as the medical literature grows, as patients’ clinical data becomes more voluminous and (perhaps paradoxically) more accessible, the need for time will not shrink and will probably grow. “Time,” the general practitioner, epidemiologist, and writer Julian Tudor Hart wrote, “is the real currency of primary care…”—words that have much broader applicability in the political economy of medicine.

This principle—its deepening of Baumol’s “cost disease”—has profound consequences for the current supply-side agenda. Our society contains the medical science and technology to fundamentally lengthen and improve the life-course experiences of its constituent individuals. But our economic science—the ideas that explain the underlying patterns of ownership, revenues, and provision of care—has not caught up to the advances in medicine. In fact, our healthcare economy today is likely constraining health outcomes: since 1980, life expectancy in the US has progressively diverged from that of other wealthy nations, translating to hundreds of thousands of excess deaths—or “missing Americans” as some researchers have cast it—each year, even as our health spending has soared.

The whole is greater than the sum of its parts: increased productivity (from capital and research investment) in the treatment of one disease may have zero impact on productivity and hence costs of the healthcare sector as a whole, while increased supply may induce further demand at the higher level of costs. A new paradigm of demand, supply, and how we understand the value of time in healthcare is urgently needed.

The true currency of care

Baumolian dynamics might, at first blush, seem to impose a hard limit on what even transformative healthcare reform could achieve: his “cost disease” is incurable. But there is reason for optimism that a new economics of care could greatly improve population health and happiness. For one thing, supply issues aside, socialized healthcare financing would achieve a rapid shift in demand that would expand access to care and improve health. Today, the demand for care is determined both by health needs and ability to pay. Eliminating the role of the latter determinant via a universal free-at-point-of-use single-payer system would achieve a salubrious, egalitarian shift in healthcare utilization. It would take the ability to pay out of the demand equation and achieve a distribution of healthcare service utilization—or equivalently, of the time of healthcare workers—according to patients’ needs and not means.

But the importance of government planning in healthcare services remains—and may become even greater should the demand shift away from private insurance ever occur. While corporations have long played a leading role in health insurance, today that role is colossal. Healthcare providers are increasingly being taken over by corporate giants that are, more and more, the employers of clinicians. Corporate providers have been found to be more costly, and to provide worse quality care. This unprecedented corporate takeover of healthcare provision has put these firms at the commanding heights of the US economy, and provides a compelling argument for going beyond socialized healthcare financing towards public and community ownership, too, as colleagues and I have argued. Meanwhile, a health planning approach to supply imbalances involving explicit public funding of new capital investments could achieve a more just and equitable distribution of healthcare infrastructure—or even a measured (and intended) increase in aggregate supply for those services for which we want to see higher average per capita utilization (i.e. primary care). These are supply-side interventions, albeit not what the Niskanen Center has in mind.

In addition to improving the quality of and access to care services through such innovations, socialized financing can achieve cost savings in both our pharmaceuticals industry and by reducing the enormous administrative complexity of our fragmented, multi-payer insurance system. High prescription drug prices stem not from Baumol’s “Cost Disease” but instead from drug firms’ intellectual property rights. Firms can price such patent-protected drugs wherever they wish, and supply limitations are artificial; a system to develop drugs with public funds and produce them immediately as generics could produce major savings. Even here, however, we should be cautious about overstating savings: the proceeds from such a shift must be accompanied by a major public investment in pharmaceutical research if we wish to maintain, indeed accelerate the quest for better treatments and cures.16 Private insurance companies, similarly, impose large meta-costs beyond the cost of care itself: premiums are spent on plan design, complex systems to deter the use of care and increase profit, exorbitant executive salaries, dividends to shareholders, marketing campaigns, and so forth. As a result, the average private insurer takes over 10 percent of their total revenues for their overhead, compared to about 2 percent for traditional Medicare or Canadian National Health Insurance. The Congressional Budget Office has hence estimated that single-payer financing could save about $400 billion annually by pushing system-wide administrative costs down to that of traditional Medicare.17 On the other side of the industry ledger, meanwhile, hospitals employ armies of billers and coders to secure payments from a multiplicity of private payers, each with their own rules and requirements,18 or even to chase patients for copays and deductibles, at enormous costs that can be halved through single-payer financing.19 Again, however, all such savings will be partially (though not entirely) offset by a redistribution of resources toward improving and expanding the delivery of healthcare to those who today experience inadequate care. For that, after all, is the primary reason why many of us fight for a better healthcare system: not to lower costs but to improve and expand the provision of care.

An egalitarian, comprehensive healthcare reform could, that is to say, accomplish a great deal on both the demand and supply side of the medical ledger. But what it cannot do is realize a surge in the productivity of healthcare that allows this all to happen on the cheap. For both conservative and left-wing visions of a future where production costs of healthcare plummet due to supply expansion or technological change, as I’ve explored, have no basis in history or in economic theory. Predictions of post-work utopian societies, whether communist or techno-libertarian in orientation, are hence fundamentally wrong, which has far broader implications for left-wing politics and organizing. While the production of goods may practically be limitless when one envisions ever-advancing technology, the provision of services—specifically those services whose basic value is measured in time—has an irrevocable and hard limit. Indeed, that is a primary reason why reducing relative inequality, and not only the absolute economic “floor,” is so necessary in the struggle for a more just society. Relative economic inequality is the exchange currency of time. In a society with only two people—one rich and one poor—a ten-fold pay differential between the two will always allow the former to work one hour in exchange for ten hours of the latter’s time, even if the pay of both were to simultaneously double or treble (or surge 100-fold) due to a space-age industrial revolution.

Yet these medico-economic realities should not be reason for sorrow. It is but a banal truism that many of the most important things we need for a good life necessitate the provision of time from a fellow human being: we need others to do the things we cannot do for ourselves because we lack the time or ability to do or learn them, or because we wish to put aside at least some of our precious moments for the pursuit of other enjoyable things. We do not desire the version of such services that contain less time because this also means they contain less intrinsic use value. Such time cannot be produced like steel, automobiles, or microchips. Time, we must acknowledge, can only be redistributed.

I draw these facts on Florida’s hospital build boom from an April 2023 article by Phil Galewitz, Lauren Sausser, and Daniel Chang in Kaiser Health News: “How a 2019 Florida Law Catalyzed a Hospital-Building Boom.”

↩U.S. Census Bureau, Total Private Construction Spending: Health Care in the United States [PRHLTHCON], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/PRHLTHCON, March 8, 2024.

↩The framing has, moreover, bipartisan appeal. Repeal of CON laws were, for instance, front and center in the Trump administration’s health policy reform blueprint issued after defeat of its Affordable Care Act reform effort. Susannah Luthi, “White House urges states to repeal certificate-of-needs laws,” Modern Healthcare, December 2, 2018; Department of Health and Human Services, Federal Trade Comission, Reforming America’s Healthcare System Through Choice and Competition, December 3, 2018.

↩Born in 1916, Roemer earned an MA in sociology and an MD at Cornell University in 1940. After medical school, he took a job at the New Jersey State Health Department, and during the war served in several federal agencies where he worked on plans for implementation of a post-war national health insurance program that never came to fruition. He returned to a state health department after the war, although his leftist political orientation and affiliations soon brought trouble, including allegations of disloyalty from the Board of Inquiry on Employee Loyalty of the Federal Security Agency. In 1951, Roemer left for Geneva to work at the World Health Organization, but McCarthyism followed: the US consulate seized his passport, and he and his family fled to Canada where he worked on Saskatchewan’s inaugural single-payer hospital program that became the model for the nation. A political thaw in the US ultimately allowed him to return home, and indeed to pursue a successful and highly productive academic career at various institutions including the University of Los Angeles California until his death in 2001. These biographical details are all drawn from the article by an article by Abel, Fee, and Brown throughout. Emily K Abel, Elizabeth Fee, Theodore M. Brown, “Milton I. Roemer Advocate of Social Medicine, International Health, and National Health Insurance,” American Journal of Public Health 98, no. 9 (2008):1596-7.

↩The Hospital Corporation of America (HCA), meanwhile, has faced allegations that it inappropriately encourages its doctors to admit patients from the emergency room as a revenue-generating measure. Samantha Liss, “Congressman calls on HHS to investigate HCA over emergency room admissions,” Healthcare Dive, September 16, 2022

↩An older, interesting study looked at the issue from a unique perspective, examining the experience of a large group practice that served patients covered by both the United Mine Workers’ and United Steelworkers’ health plans. In the late 1970s, the mine workers (and their families)—but not the Steelworkers —for the first time had to start paying significant cost-sharing (e.g. copays) for care. As economic theory would predict, this produced a drop in demand for these workers—and a quick drop in the amount of care (and treatment costs) they received from the group practice. However, at the same time, the Steelworkers — whose coverage did not change—actually saw an increase in treatment costs. Fahs MC. Physician response to the United Mine Workers’ cost-sharing program: the other side of the coin. Health Services Research 27, no. 1 (1992): 25-45.

↩- ↩

For a more complete discussion of these issues, see: Adam Gaffney, David U. Himmelstein, Steffie Woolhandler, and James G. Kahn, “Pricing Universal Health Care: How Much Would The Use Of Medical Care Rise?” Health Affairs 40, no. 1 (2021): 105-112; Adam Gaffney, Steffie Woolhandler, and David U. Himmelstein, “The Effect of Large-scale Health Coverage Expansions in Wealthy Nations on Society-Wide Healthcare Utilization,” Journal of General Internal Medicine (2019). Demand, that is to say, predominantly determines the distribution of utilization of services, and supply, their aggregate volume. Egalitarian financing hence redistributes use; stable supply constrains it.7 One implication of Roemer’s law is that supply expansion will likely fail as a strategy of cost control, even if it is needed to meet demand. On the contrary, supply growth (or capital expansion) can drive both use and costs—something long recognized in nations with universal health systems that have been compelled to regulate supply. Roemer and Shain, for instance, observed in 1959 that “soon after the introduction of universal-coverage hospitalization insurance plans,” Canadian provincial governments found that “they had to control the construction and even the setting up of new hospital beds.” In part, this was to control the total costs of the system once ability-to-pay was removed as a determinant of demand.

↩The relationship between supply and overall stent provision is uncontroversial, as is the ongoing deployment of many “low value” stents. However, whether supply drives low-value stents in particular is the subject of an ongoing study by the author with colleagues.

↩Gaffney A, McCormick D, Bor D, Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU. Hospital Capital Assets, Community Health, and the Utilization and Cost of Inpatient Care: A Population-Based Study of US Counties. Medical Care 2024;10.1097.

↩In the 1970s—a time when national health reform of some type seemed like it was probably around the corner—there was something of a consensus to this effect. In 1964, New York State passed the first “certificate of need” (CON) law, which required hospitals to justify new buildings or equipment on the basis of community medical need; other states followed, culminating in passage of the 1974 National Health Planning and Resources Development Act (NHPRDA), which required that states set up health planning bodies to regulate hospital expansion. However, as Evan Melhado describes in his history of the US “health planning” movement, CON laws were designed to fail. “Planners had promised cost control,” Melhado notes, “but in the end they lacked the will and the tools to deliver it.” (See: Melhado EM. Health planning in the United States and the decline of public-interest policymaking. Milbank Q 2006;84(2):359–440.) Ultimately, powerful vested interests in provider and insurance lobbies defeated what many assumed to be the inevitable arrival of a national health insurance system. Reliant on private investment, healthcare remained regulated by CON laws in a fundamentally reactive way, limiting or negating the benefits of this planning instrument. The point, then, is not to go back to CON: it is to move beyond it to a proactive system of health capital planning.

↩Reducing time spent on non-clinical tasks—e.g. billing or documentation-geared to billing—would be an exception here. I deal with the issue of productivity defined as health rather than services in the following footnote.

↩Economists will take issue with this contextualization of medical productivity. People do not spend time with a physician or a nurse or in a hospital bed for its own sake and, some would argue, they use such services for the purpose of improving their health. The “output” of health services, this argument might go, is not the good or service itself—it is not the physician visit or the hospital day or the hour spent in the operating room—but rather it is the incremental gain in health itself. From this perspective, new technology does improve the productivity of healthcare. For instance, if a two-hour long surgery for cancer had (hypothetically) a 20 percent chance of curing a patient of some cancer twenty years ago and a 40 percent chance today, is that not a productivity gain for the surgeon even if input-time is unchanged? And indeed, quality adjustment is used by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics in its calculation of the consumer price index (CPI) for at least some goods and services. Regression analysis and “hedonic adjustment” is used to, for instance, account for improvement in the quality of say, pants and televisions, over time. The CPI, in turn, is used to adjust for inflation and calculate “real” economic growth. Productivity growth can be defined on the basis of real, not nominal, growth. Hence, quality adjustment can, theoretically, be a determinant of productivity growth even if the gross number of outputs per worker-hour remains unchanged. A string quartet might be more productive today than two hundred years ago, in other words, if the sound of the music got better. How workable, and how meaningful, such quality adjustment might be for healthcare (much less music) is rather uncertain, however. For specific new innovations, such as the invention of a new drug, quality adjustment is at its most possible and meaningful. One study, for instance, looked at the cost of a new expensive treatment for multiple myeloma, and found that when adjusted for quality—as measured in quality-adjusted life years (QALY) gained—new drugs actually “reduced” the cost of treatment for that specific disease even if the overall nominal costs actually rose. Fair enough, I suppose. However, there are multiple reasons why such “quality adjustment” has limited utility when it comes to thinking about the financing of healthcare, and social services more generally. For one thing, measuring the output of healthcare not in terms of goods and services provided but rather by some less tangible, partially conceptual experience raises thorny practical questions. Computing the health-benefit of health services in aggregate, rather than a specific new pharmaceutical agent that has just been introduced, is technically and indeed philosophically challenging. It requires that we first objectively and quantitatively define health, a seemingly obvious but contested concept; this is effectively the quality-adjusted life year, or QALY, although it is one thing to use QALYs as metrics of relative cost-effectiveness among medical services and another to use them to weight the benefits of the totality of medical care against other goods and services. This approach then requires that we compute the health production of a doctor-hour or nurse-hour, today compared to fifty years ago, isolating out all the other factors that impact health. These are, however, practical limitations that could be overcome with sufficient (indeed, heroic) assumptions. Putting them aside, however, there is a deeper problem with quality adjustment in this context: it has little relevance to the financing of health services in aggregate. If infectious disease treatment advances and patients with infectious diseases live longer (as I describe later with respect to tuberculosis), yet infectious disease doctors spend precisely the amount of time in aggregate treating infectious disease patients, there will still be no change in the infectious disease workforce and no reduction in the amount of funding needed to finance infectious disease treatment. Society would be healthier, but it would not pay less for health services in terms of real resources. Indeed, as fewer are cut down tragically early in life, it may well pay more, for the reasons I discuss elsewhere.

↩Likely reflecting, in part, the growing intensity of care and complexity of illness of hospitalized patients. Additionally, these figures should be interpreted with the understanding that hospitals’ have been progressively providing more outpatient care. Although the figure reflects outpatient visits as “inpatient equivalents” by using revenue as a proxy, this assumes that all forms of care require similar nursing inputs. The larger point, however, is that there is little evidence for an increase in productivity.

↩American Hospital Association, Hospital Statistics 1972.

↩Colleagues and I estimated, for instance, that $155 billion could be saved from lowering drug prices through a combination of single-payer negotiations and compulsory licensing—but that this would (or should) be offset by $140 billion to cover the costs of increased prescription drug use from expanded coverage, public drug R&D programs, and needed pharmaceutical regulatory reforms.

↩However, we may envision some new costs from assisting displaced workers in the insurance industry from such a shift—a policy which would be required not only by normative considerations but by the need to overcome the political opposition that can be expected whenever a major sector is socialized.

↩The cost of this administrative workforce is reflected in the “price” of a patient bed day, even if much of it is not socially useful. Single-payer financing of hospitals with global budget “lump sum” payments could, as colleagues and I modeled, produce substantial savings through downsizing hospital administration, and eliminating profits, beyond savings, from simplifying payer-side administration. See: Gaffney AW, Himmelstein DU, Woolhandler S, Kahn JG. “Hospital Expenditures Under Global Budgeting and Single-Payer Financing: An Economic Analysis, 2021–2030.” International Journal of Social Determinants of Health and Health Services (2023).

↩Lowering exorbitant incomes of some employees might, similarly, create some savings. But again, realism is needed. For this article, I analyzed Census microdata, which suggests that even a radical, unprecedented compression in pay for hospital sector workers—say raising minimum pay to $50,000 while capping compensation at $200,000—would have little to no impact on aggregate hospital costs, and could even increase them if accompanied by workforce expansion. Specifically, I analyzed 2022 Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement microdata. Total wages and income for workers reporting employment in the hospital industry amounted to $618 billion in 2021, or about 47 percent of total hospital expenditures that year per spending data from Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ National Health Expenditures Accounts (NHEA). If it were somehow possible to create a maximum income of, say, $200,000 across the entire hospital sector, total hospital employee pay would fall to $554 billion, or about 5% of total hospital expenditures. However, that would leave many hospital employees earning poverty wages. If, at the same time, such reform was accompanied by an increase in pay for low-paid workers, and say minimum pay of $50,000, total hospital spending would be basically unchanged, with $613 billion in wage and salary costs sector-wide. If health benefits were accounted for, differences, relatively speaking, would likely be even smaller. Obviously, any increase in the size of the workforce, as promoted in “supply-side” reforms described earlier, would offset such savings. Indeed, in such a scenario, spending could actually rise.

↩

Filed Under