Lea este artículo en español aquí.

Gustavo Petro’s presidency marks a turning point in Colombia’s democratic history. Not only is Petro the first leftist to govern the country, but he has also made achieving peace a central objective of his progressive agenda. The Colombian armed conflict has been the most violent in Latin America in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries: it has left over 450,000 dead, 50,000 kidnapped, and 8 million displaced. Beginning in the mid-1960s with roots dating back to the 1950s, it is also the region’s longest running conflict. Dozens of guerrilla groups, dissidents, and factions have emerged within this landscape, alongside paramilitary structures, drug cartels, and state-led violent actors.

By refusing to comply with the conditions of the 2016 peace accords, Petro’s predecessor Iván Duque (2018–2022) severely weakened the agreement reached between former President Juan Manuel Santos and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia-People’s Army (las Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia-Ejército del Pueblo, FARC-EP). Petro in turn has made a commitment to comprehensive peace with the National Liberation Army (Ejército de Liberación Nacional, ELN)—currently the largest guerrilla group active in the country—as well as FARC-EP dissidents who emerged after 2016 and far-right paramilitary groups which have remained active following the 2005 disarmament agreement. The current negotiations are unfolding amid intensifying violence and deteriorating security conditions, a result of both increasing levels of coca production and the presence of more than fifty armed organizations in the country.

Today, the ELN is stronger than ever: it has more armed resources and a much larger territorial presence than it did seven years ago. In 2010, the ELN had approximately 1,800 members, while current estimates suggest that today, 3,500 to 4,000 members are adhering to an intermittent ceasefire with the government, which was agreed upon in August 2023. This is not the first time that the ELN—which emerged as a Guevarist guerrilla force in 1964—has negotiated with the Colombian state. Peace negotiations with various armed organizations have been major objectives for most administrations since the early 1980s. These efforts, however, have been hindered by a state that lacks the capacity to administer the territory contained within its borders. The profits of illicit economies, including illegal mining and drug trafficking, have fueled the near constant violence in the country’s periphery.

President Petro’s recent peace process is exceptional in two ways. First, it is novel that a negotiation agenda has built on the advances of a previous peace process—in this case, Juan Manuel Santos’s 2016 peace accord with the FARC-EP guerrilla army. Second, unlike past processes, the government is proposing simultaneous negotiations with distinct and oppositional groups, including left-wing guerrillas and right-wing paramilitaries, arguing that a peaceful resolution requires engaging with all violent actors at the same time. In the government’s eyes, preventing all actors from continuing to spawn new dissident groups will thwart the repeated cycles of violence that have plagued the nation in recent decades. The process has already seen major setbacks, with the ELN suspending talks just last week, only to announce days later that they would resume ahead of negotiations scheduled for April.

The stakes are high: the success of Petro’s “maximalist” peace agenda would lead to a significant reduction in violence and increase the state’s legitimacy and democratic processes—especially with respect to the government’s commitment to integrating dissident armed groups. Importantly, reaching a peaceful resolution with the ELN would validate Petro’s progressive approach to the conflict. Unlike past administrations that viewed the armed conflict as solely a military struggle, the Petro government sees it as a response to structural inequities reflected in land distribution and the absence of economic opportunities. In a country shaken by violence for much of the last century, the ambitious promise of peace has the potential to shape Petro’s legacy.

Failed negotiations

Successive Colombian governments have struggled to contain armed conflict. After the end of the Rojas Pinilla dictatorship (1953–1957), the state operated according to the principles of the National Front (Frente Nacional)—a bipartisan agreement alternating power between the Liberal and Conservative parties.1 Dominant until 1982, the National Front governments aimed to lay the foundations of the modern Colombian state, investing in infrastructure, basic social policies, and industrialization. Up until the late 1970s, the incipient problem of the armed conflict was not a priority, and repeated governments failed to address the structural conditions that fueled violence in the countryside. Land reform remained evasive, and the distribution of wealth was characterized by stark inequality.

The first formal attempt to negotiate with guerrilla groups occurred in 1984 under the Belisario Betancur and involved both the FARC-EP and the M-19, an urban guerrilla group active until 1991. Since then, most negotiation processes have faltered in their efforts to clearly define the societal and democratic transformations necessary for peace between the guerrillas and the state.

Inspired by a radical form of agrarianism, the FARC-EP believed it was possible to seize power through revolutionary means; after 1982, this objective was more viable due to the weakness of the Colombian state. The ELN, with firm Marxist-Leninist convictions, was skeptical of any calls for dialogue, refusing to participate in negotiations throughout the 1980s and ‘90s. The ELN argued that any negotiation necessitated an overhaul of Colombia’s deeply extractive economic and social model, and such changes would likely be impossible in a peace process that upheld the legitimacy of the Colombian state.

Both the FARC-EP and the ELN guerrillas accumulated resources and expanded their territorial control after the mid-1980s. By the 2000s, FARC-EP had reached 18,000 combatants and was present in a third of the country; the ELN was composed of 5,000 members, mostly concentrated in particular strongholds in Antioquia, Bolívar, and the Pacific coast. Much of this territorial growth was linked to profit flows from illicit economies associated with kidnapping and extortion—the drug trade in the case of the FARC-EP, and smuggling and illegal mining in the case of the ELN. By the late 1990s, the drug business totaled $1.2 billion, and kidnapping became the main source of income for the ELN. Meanwhile, the state had little presence in regions under guerrilla control. More than 300 municipalities lacked even a single police officer, and Colombia ranked among the top three Latin American countries with the highest levels of inequality.

The Santos shift

Under President Álvaro Uribe (2002–2010), the government’s Democratic Security Policy rested on a straightforward premise: peace in Colombia would only follow from the military defeat of the guerrillas. Nearly 4 percent of Colombia’s GDP was invested in security and defense, funneled into expanding military structures, purchasing equipment, and increasing the number of police and military personnel by over 30 percent, from 313,000 to 440,000. Paramilitaries, on the other hand, were largely spared from state-led military campaigns. Over 30,000 paramilitaries benefited from the controversial Justice and Peace Law, and the government offered the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia, AUC), a major far-right paramilitary group, a legal framework for demobilization. Uribe’s policies halved both the number of fighters and territorial presence of the FARC-EP and the ELN. Still, although the guerrillas were strategically defeated, they remained resilient in the country’s border regions, which transformed into bastions of entrenched conflict after 2010.

While initially continuing Uribe’s confrontational policy, Juan Manuel Santos soon changed course, seeking to promote peace dialogues with the FARC-EP and the ELN. While the negotiations did not involve a ceasefire, in the years prior to reaching a peace deal with the state the FARC-EP significantly deescalated, demonstrating a willingness to put down arms. In 2012, the FARC-EP carried out 824 armed actions in 190 municipalities. By 2015, the number of actions dropped by 85 percent, while 2016 marked the first year in decades in which no Colombian security personnel was killed as a result of a guerrilla action.

The 2016 FARC-EP agreement outlined a transitional justice framework that offered lighter sentences for the guerrillas and special jurisdiction in exchange for the fighters’ commitments to truth and justice processes, reparations, and non-repetition. The agreement also committed the government to strong political protections in former FARC-controlled territories. These promises were largely unkept, with over 360 FARC-EP combatants and 1,800 social leaders killed in recent years, in part a result of the power vacuum that emerged following the deal. Finally, a tripartite international verification and monitoring mechanism formed by the guerrillas, the Colombian government, and the United Nations carried out a disarmament process that collected approximately 1.2 rifles for each demobilized guerrilla fighter.

While negotiations with the FARC-EP progressed, the Santos government explored parallel dialogues with the ELN, announcing the start of an official peace negotiation on March 30, 2016. The agenda had six central items: 1) societal participation for former members, 2) democracy for peace, 3) victim justice, 4) transformations for peace, 5) security and disarmament, and finally, 6) political rights. The two most powerful structures of the ELN—the Western War Front (Frente de Guerra Occidental, FGOC) in Chocó and the Eastern War Front (Frente de Guerra Oriental, FGO) in Arauca—never demonstrated a clear position on the dialogues. Despite ELN representatives pursuing a commitment to peace on the negotiation table, the FGOC and FGO continued armed actions, harassment campaigns, and kidnappings.

Negotiations officially commenced in February 2017, but beyond the negotiating table, confrontations in Chocó and Arauca would intensify by September. After the election of right-wing president Iván Duque in 2018, multiple outbreaks of violence during a brief ceasefire paralyzed ongoing dialogues.2 The process came to a deadly close with the ELN’s January 2019 attack against a police cadet school in southern Bogotá, which left twenty-three dead and ninety injured. Despite Santos’ major breakthrough with the FARC-EP accords, peace after 2016 continued to be elusive.

The arrival of Gustavo Petro

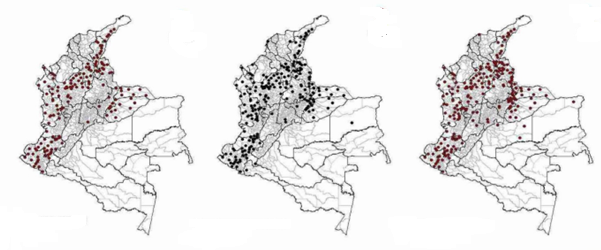

Under Duque, prospects for dialogue with the ELN were severely limited. The frosty relations between the government and the guerrillas—alongside the state’s failure to comply with much of the FARC-EP agreement—led to a profound deterioration in the country’s security conditions. With the FARC-EP’s disarmament, the ELN was able to consolidate power and strengthen its position in places where it already had a strong foothold. It secured quasi-hegemony in several territories (see map 1), including Arauca, the Catatumbo region, the southern part of Bolívar, the central and northern parts of Chocó, and specific locations in Antioquia, Cauca, and Nariño.

Numerous dissident groups made up of former FARC members also proliferated across the country, claiming to be the legitimate heirs of the demilitarized guerrilla and entering into violent confrontations with the ELN. Other armed groups also remained active, including the Gulf Clan, the largest heir of the demobilized paramilitaries. In total, the number of armed groups opposing each other and mobilizing against the state rose to about fifty.

Map 1: Territorial Presence of the ELN, 2018–2020

Gustavo Petro, who began his presidential term in August 2022, arrived on a scene marked by extreme violence and territorial conflict between multiple groups, all of whom had a distinct relationship with each other, the land, local communities, and the state. In light of these circumstances, Petro called for “Paz Total” or “Total Peace” (Public Order Law 2272 of 2022) as part of his National Development Plan (Law 2294 of 2023), which considers violence from the armed conflict a priority. This approach contrasts with Iván Duque, whose campaign objected to many of the 2016 peace agreement’s most important components, such as special jurisdiction for former guerrilla members. Duque’s resistance impeded the implementation of the peace deal; the Kroc institution found that comprehensive compliance with the agreement barely reached 2 percent under his administration. Under these conditions, Petro’s task is to regain trust in the government’s promises and commit to state-backed investment in development, protection, and socioeconomic transformation in the country’s periphery.

Several obstacles remain ahead for the Colombian state. During previous negotiation processes with the ELN, maximalist agendas for peace were vague and generalist. One of Petro’s main challenges will be to translate the ELN’s broad demands for social and economic transformation into specific agreements that can be adequately monitored. The current negotiations also lack an agreement on a progressive disarmament scheme. This was one of the most successful elements of the FARC-EP peace deal, though it did mean the guerrillas lost their main leverage to demand full state compliance with the agreement.

Since the mid-1980s, most peace processes in Colombia have not involved a ceasefire between warring parties. The few cases where ceasefires were agreed upon—the 1984 agreement between La Uribe and the FARC-EP, as well as the Corinto deal with M-19—ultimately resulted in failure. This recent occasion established ceasefire as a goal from the outset. Though it was named as a priority for both the government and the guerrillas, it took three rounds of negotiations to reach the first real commitment to reducing hostilities. The first ceasefire was announced from August 3, 2023 until early 2024, extending for six months and marking a complete stop of armed actions, which would be closely monitored. So far, there has been a de-escalation in the ELN’s tactics, with the exception of a guerrilla killing committed in August 2023 in San Vicente del Chucurí. Petro’s negotiation team also has a broader and more diverse composition than previous teams, aiding in certain aspects of the negotiations. The team has greater gender parity, ethnic diversity, and includes political figures such as Senator Iván Cepeda and José Félix Lafaurie, the president of the Association of Colombian Ranchers (Federación Nacional de Ganaderos, Fedegan).

In 2016, negotiations collapsed largely as a result of the ELN’s decentralized and federal composition; those present at the negotiating table did not control those in the FGO or FGOC. Though the ELN has central command bodies, the group does not have a vertical decision-making process, marking a stark contrast with the FARC-EP. The ELN engages in horizontal dialogue with the war fronts to come to its decisions. Because of this, ensuring compliance with agreements is difficult to guarantee and often leads to conflict within factions. The lack of unity among the fronts has torpedoed past negotiation attempts. The success of the current efforts, with Petro’s progressive yet nonetheless maximalist approach, remains to be seen.

Achieving “Paz Total”

The ELN has become significantly more powerful since 2017. In addition to gaining territory in the peripheries, the group has almost entirely consolidated several areas once under the control of the FARC-EP. The number of ELN fighters is estimated to have doubled in just seven years, surpassing 4,000 in 2023. The group has also strengthened its binational status, attaining a more noticeable presence in the Venezuelan states of Zulia, Apure, Táchira, and Amazonas.

In the context of the ELN’s strengthened position, the progress of Total Peace will depend on several aspects. First, the government’s dialogue with the ELN can only progress if it secures some degree of consensus among the various fronts, including the FGOC and the FGO. Second, it’s unclear whether the ceasefire will strengthen public trust in the negotiations, particularly among communities that have suffered the effects of the armed conflict. Finally, the advancement of negotiations has the potential to mitigate internal conflicts among armed groups—the ELN, FARC-EP dissidents, and far-right remnants of post-paramilitarism—each of which have their own dynamics centered around illegal economies.

The negotiations are ongoing, and the sixth cycle of dialogues (each lasting twenty days) between the guerrilla group and the government has already ended. Meanwhile, the ceasefire has been extended until August 2024, and the ELN has agreed to suspend extortionate kidnappings and the recruitment of minors. For Petro’s government, among all the negotiations being pursued within the framework of Total Peace, the negotiation with the ELN is the most advanced and holds the greatest promise of success. It’s crucial that the government is able to reach a final agreement, even if negotiations with other insurgent groups crumble.

The success of the dialogues would satisfy Petro’s campaign promise for peace. On the other hand, failure would provide a significant victory to Petro’s right-wing opponents, who advocate for the return of a militaristic approach in confronting guerrilla groups and oppose government investment in social protection and economic transformation in exchange for disarmament. Thus, the consolidation of left political power in Colombia could hinge on the fate of these negotiations.

Even if Petro manages to sign a peace agreement with the ELN, he would still need to demonstrate that the guerrilla group’s exit from the battleground will reduce overall violence, kidnappings, and drug trafficking, instead of creating a power vacuum for other armed groups to fill. Violence has already shifted to major cities, and many fear a repeat of the FARC-EP peace deal, in which the disarmament of one major armed group inadvertently strengthened another. In any case, a peace deal with the ELN would entail the reintegration of 5,850 fighters into civilian life, according to military intelligence estimates. After decades of militancy and drug trafficking in remote areas of the country, a reintegration effort of this scale will involve strengthening the role of civil society.

Because the ELN is a confederation of regional groups—each representing specific issues in their localities—the negotiations present an opportunity for the government to deliver the territorial transformations that communities have long demanded. These changes, however, entail long-term investments in civilian infrastructure and access to basic provisions in order to correct for decades of neglect from the state. Such an immense task—extending far beyond the stipulations brokered at the negotiating table—appears difficult to achieve in the two and a half years that remain of Petro’s term.

This essay was translated from Spanish for Phenomenal World by Eduardo Gutiérrez.

Some of the Front’s proposals regarding the distribution of power and the administrative structure of the State remained unchanged for two more presidential terms: those of the Liberal Alfonso López Michelsen (1974-1978) and the Conservative Julio César Turbay Ayala (1978-1982).

↩After a ceasefire in effect since early September, there was a notable resurgence of armed activity in Arauca, Norte de Santander, Nariño, and Antioquia. A triggering set of actions were the three attacks that took place at the end of that month in Barranquilla and Soledad (Atlántico) and in Santa Rosa del Sur (Bolívar); this resulted in a total of eight police officers dead and more than forty injured, prompting Juan Manuel Santos to suspend the dialogue. In response to this event, the ELN carried out sixteen more terrorist actions between February 10 and 13 in Antioquia, Cesar, Nariño, Norte de Santander, Arauca, and Cauca.

↩

Filed Under