Lea o artigo em português / Lea este artículo en español.

Since the early 2000s, Argentine development finance has undergone a profound transformation.1 Amid cyclical debt defaults and endless negotiations with Western investors and the IMF, Chinese overseas investment loans have slowly crept to the fore. Between 2007 and 2020, Argentina received $10.65 billion in investment from Chinese companies, concentrated in the energy, mining, and financial sectors.2 Today, Argentina is the fourth-largest recipient of Chinese loans in the region, securing around $17 billion in total. These loans have primarily supported transportation infrastructure, energy projects, and the enhancement of Argentine exports. In 2022, President Alberto Fernández agreed to open financing lines with China totaling nearly $23 billion through the Strategic Dialogue for Economic Cooperation and Coordination (DECCE) and Belt and Road Initiative, though the latter is still pending activation.

It’s within this changing borrowing landscape that Javier Milei, the self-defined “first true free-trade reformer and libertarian president in the history of the world,” has been elected. Milei won the ballot against the former Minister of Finance, Sergio Massa, in a country with 140 percent inflation rate and plummeting exports thanks to a drought that resulted in a $19 billion loss, nearly 3 percent of Argentina’s GDP.

Economically, Milei raises a sense of déjà vu reminiscent of neoliberal figures from the 1970s, 1990s, and the Macri era. His political party and cabinet are drawn from earlier administrations, with figures like Ricardo Bussi (son of the dictator and governor of the Tucuman Province), and members from Menem’s administration, including Menem’s nephew, Martín Menem, as president of the Chamber of Deputies. Notably, a significant number of former ministers from Macri’s government—Patricia Bullrich, Luis Caputo, Santiago Bausili, among others—have also joined Milei’s cabinet.

Milei advocates for radical free trade reforms and a robust adjustment policy. Hoping to usher in a new era of substantial indebtedness from Western finance, he originally pledged to sever ties with “communist” governments like China and Brazil and notoriously promised to dollarize the economy and dismantle the Central Bank.

But less than a month since his election, Milei’s orientation towards China saw a dramatic shift: Argentina currently holds a net Central Bank reserve of negative $10 billion, with gross reserves amounting to $23 billion, 75 percent of which are tied up in a swap arrangement with China. When the Chinese Embassy suspended the arrangement, Milei was ironically forced to apologize to Xi Jinping in his first political move. But Milei’s letter was not enough—China suspended activating the 47 billion Renminbi (equivalent to $6.5 billion) of the swap.

The trajectory of Milei’s orientation towards China raises questions regarding deeper developments in the global financial landscape. It suggests that there’s more at stake than ideology alone—that in certain contexts, the US and its affiliated financial institutions can no longer credibly claim to finance the development needs of the global South, and that Chinese investment is here to stay. Furthermore, it indicates that not all global South countries are equally empowered by rising geoeconomic competition. On the contrary, some find themselves doubly trapped between the global powers.

Debt Cycles

In December 1982, Argentina’s central bank nationalized nearly $17 billion of private debt, concluding a period of Kissinger-backed dictatorship characterized by some of the earliest experiments with neoliberal restructuring. The decision paved the way for the debt crisis of the 1980s and subsequent deindustrialization and adjustment reforms policies in hand with social repression.

The Argentine economy has remained on this cyclical trajectory since: significant borrowing triggers an economic crisis which is then used to justify austerity measures and privatization. Rather than stimulating economic growth, these measures often worsen the crisis and prompt a period of capital outflow.3 In subsequent elections, the ruling center-left coalition refrains from challenging the cycle, choosing instead to renegotiate and repay the debt.

It’s because of this pattern that former President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner designated Argentina as a “serial payer.” The strategy can have temporary gains in favorable exogenous circumstances, like a commodity boom. But during an international recession, the strategy couples with structural adjustment policies and sparks enormous dissatisfaction. The right-wing coalition eventually returns to power.

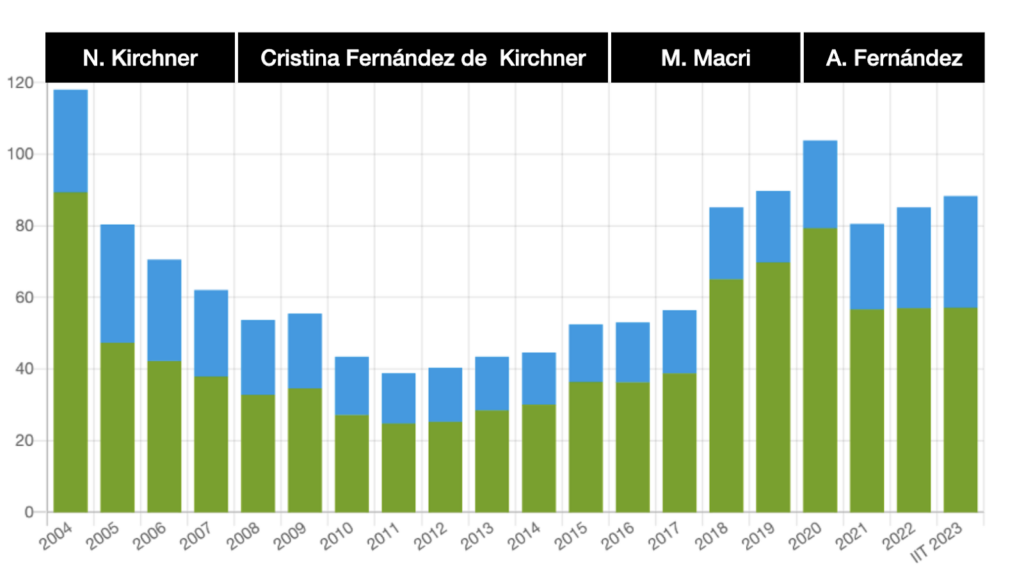

Figure 1: Argentina as a “Serial Payer”: Gross debt by currency as a percentage of GDP

Argentina’s debt cycle has been persistently stimulated by its toxic relationship with the IMF. In 2018, the disastrous effects of IMF lending reached new heights, surpassing Argentina’s debt-bearing capacity and sparking a capital outflow that contradicted IMF statutes.4

IMF policies have been guided by a distinct political agenda: Mauricio Claver, the executive director at the IMF and a crucial adviser to the Trump administration on Latin America, asserted, “Everything Trump did at the IMF was to assist Macri and prevent Peronism from returning to the ‘Casa Rosada’ (Argentine Presidential Palace).” By prioritizing the exclusion of the political left, these policies inadvertently opened the way for the right.

Luis Caputo, now serving as Milei’s Minister of Economy, previously held the same position during Macri’s administration. Caputo, an economist with a background at JP Morgan and Deutsche Bank, implemented a currency flight mechanism via the Central Bank during Macri’s tenure. This involved dollar auctions below market rates, resulting in a substantial loss of 66 billion pesos. The connection of this loss to funds from Macri’s record IMF loan was later revealed, raising concerns about financial outflows. In a surprising revelation, Milei himself stated in a 2018 interview, “Caputo sold out, he smoked $15 billion from the IMF, and he’s responsible for the disaster in the Central Bank.”

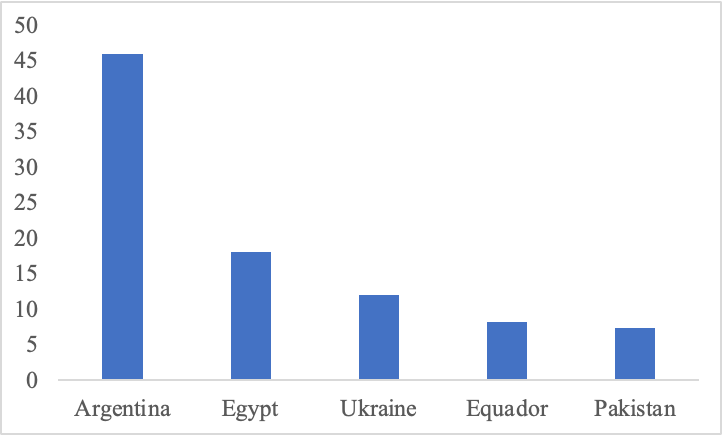

Figure 2: Most Indebted Countries with the IMF, in USD Billions.

Upon assuming power, former President Alberto Fernández government pledged to break away from neoliberalism and chart a path toward growth. However, the debt restructuring led by then Minister of Economy Martín Guzmán, involved requesting a new loan from the IMF within the framework of the Extended Facilities Program (EFP) and gaining approval in Congress. Historical evidence indicates that structural adjustment programs, be they “soft” or “strict,” have consistently fallen short of resolving issues in Latin America, often exacerbating them instead.5

The agreement itself proved to be inflationary and significantly curtailed the government’s ability to implement assertive policies against inflation. Following the formalization of the agreement with the IMF, Guzmán resigned, and Sergio Massa, a seasoned politician, assumed the role of Minister of Economy.

An Opening for China

It’s in the aftermath of decades of lending on the part of Western institutions that China has risen as an appealing alternative. Chinese loans hold significant advantages over their Western counterparts. While Western finance comes with domestic political and economic conditionalities, China offers non-conditionality loans for large infrastructure projects. After a five to ten-year grace period, recipient countries are expected to pay back the loans thanks to the economic growth they are expected to generate.

Chinese loans do require Chinese technology to constitute 30 to 40 percent of the recipient country’s imports, broadening China’s export markets. Overall, Western finance has been way more speculative and short-term than the Chinese “patient” capital.6 As Table 2 indicates, state-to-state loans from China to Argentina using sovereign guarantees amounted to nearly $7.8 billion, and most of the financing lines went to transport and energy projects.

Table 1: Comparative table between Western and Chinese Finance in Argentina

| Aspect | Western Finance | Chinese Finance |

|---|---|---|

| Conditionalities | – Domestic political and economic conditionalities. – Mostly related to adjustment programs. – Geopolitical conditionalities | – Non-domestic policy conditionalities. – Tech clause: Minimum 30-40% of Chinese technology imports to boost Chinese exports.7 – Cross-default clauses: If one project stops, all are affected. |

| Cycle | – Speculative and short-term – Doesn’t generate repayment conditions – Usually outflows of the country – Linked to US financial expansion | –Related to projects in the real economy (hydro-dams, solar plants, export lines, etc.) – Expects to generate repayment conditions – Swaps are long term, “patient” capital.8 They do not cost anything prior to activation. – Linked to Chinese material expansion. |

| Interest Rate | – IMF: Around 10% | – Chinese loans and swaps are lower than market interest rates. – Loans around 3%, swaps around 6%. |

| Adaptability | – Low | – High |

Table 2: Loans channeled by development banks from China to Argentina (2010-2019). By lending agency, project, amount, interest rate and maturity.

| Year | Lending Agency | Project | Million USD | Interest rates | Maturity (years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | China Development Back (CDB) y CITIC | Supply of locomotives, passenger wagons, spare parts, tools, technical documents, technical service and technical training for the San Martín Railroad | 273 | Libor + 3.15% | 10 |

| 2010 | Export-Import Bank of China (CHEXIM) | Supply of passenger wagons, spare parts, tools, technical documents, technical service and technical training for the San Martín Railway | 114 | Not available | 8 |

| 2014 | China Development Back (CDB) y ICBC | Rehabilitation of the Belgrano Cargas Railway | 2100 | 6-months Libor Libor + 2.9% interest rates, 0.125% commitment, and 0.20% management fee | 15.5 (with a grace period of 4.5 years) |

| 2014 | China Development Back (CDB); ICBC y Bank of China (BoC) | Hydroelectric dams on the Santa Cruz River | 4714 | 6-months Libor Libor + 3.8% interest rates, 0.125% commitment, y 0.20% management fee | 15 (with a grace period of 5.5 years) |

| 2017 | Export-Import Bank of China (CHEXIM) | Cauchari I, II and IIIA photovoltaic solar parks | 331 | Interest rates 3% (Preferential Buyer Loan – PBL) + 0.75% commitment fee and 0.75% management fee | 15 (with a grace period of 5 years) |

| 2019 | China Development Back (CDB) | Acquisition of rolling stock for the Roca Electric Railway | 236 | 6-months Libor Libor + 2.4% margin | 10 (with a grace period of 3 years) |

| Total | 7768 |

Chinese swap lines have played a crucial role in stabilizing Argentina’s macro-economy since 2009, strengthening the country’s reserves in the Central Bank without additional costs if used as a reserve mechanism. Since 2008, the People’s Bank of China has engaged in bilateral swap agreements (BSAs) with foreign central banks, utilizing these agreements to offer short-term liquidity support to partner countries beyond the Bretton Woods institutions. Argentina has been a significant beneficiary of these agreements. The initial currency swap, valued at 70 billion yuan ($9.98 billion), was inked in 2009 between the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) and the Central Bank of Argentina (BCRA) during Cristina Fernández de Kirchner’s presidency.

In 2017, under Macri’s administration, the PBoC and BCRA renewed the bilateral currency swap agreement for 70 billion yuan. An additional currency swap deal for 60 billion yuan was signed in 2018, expanding the total to 130 billion yuan (US$20 billion). In 2022, Alberto Fernández renewed and extended the swap with China to 150 billion yuan (US$23.4 billion). During Sergio Massa’s tenure as Minister of Economy, two additional tranches were enabled: the first, equivalent to $5 million, and when depleted, a second tranche was activated for $6.5 billion. From this latter amount, funds were allocated to make three payments to the IMF in yuan: on June 30 for $1.08 billion, on November 1 for $796 million, and on the seventh of the same month for another $884 million.

Table 3: Argentina Central Bank’s Reserves, disaggregated August 2023

| Concept | USD Billion |

|---|---|

| 1. Gross International Reserves | 23.8 |

| Gross liabilities — Swap lines — China (Of which activated) — BIS RR FX deposits Other (incl. deposit insurance) — SEDESA — Other | 34.1 20.9 17.9 6.5 3.0 10.3 2.0 1.8 1.0 |

| 2. Net International Reserves | -10.3 |

| Gold SDR Liquid reserves | 3.8 0.0 -14.1 |

| Memorandum item | |

| Nominal Interest Rates (program definition) Central Bank Non-deliverable forward position | -6.3 3.1 |

Chinese Trade and Industrial Transformation

Increased Chinese investment comes with a price. Since the early 2000s, China has overtaken Argentina’s traditional economic partners, including the United States and Europe. Currently, China ranks as Argentina’s second-largest trading partner, following Brazil. Typically, Chinese trade constitutes 8 to 10 percent of Argentine exports. However, Argentina’s trade balance has experienced growing deficits, particularly with China and the United States.

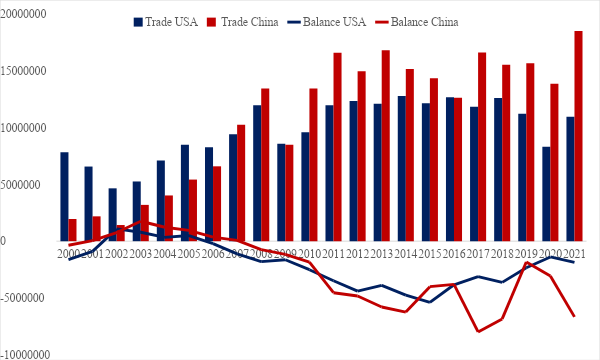

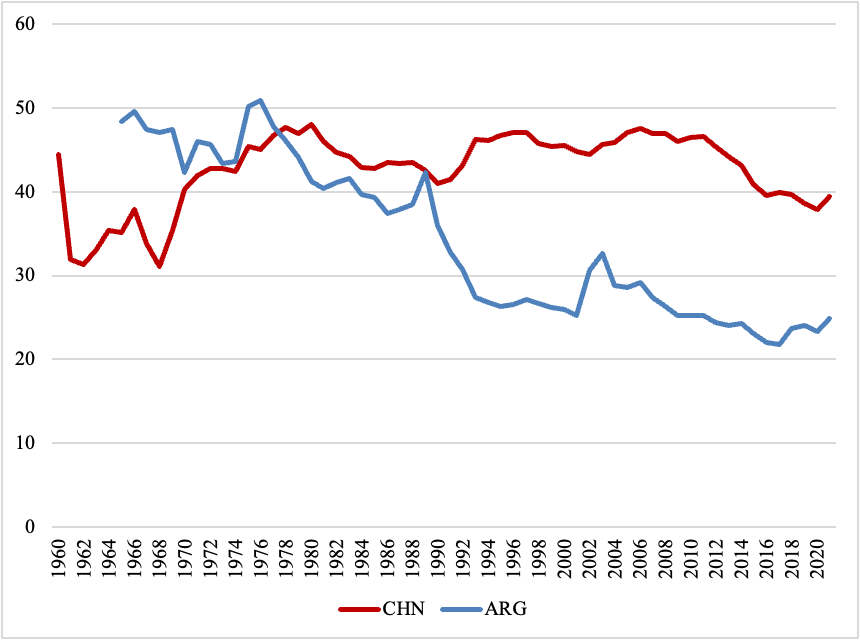

Figure 3: Argentina’s Trade Balance with the US and China

While China escaped from “shock therapy” policies,9 Argentina suffered the consequences of recurrent neoliberal waves, the industrial development in the countries experienced bifurcating paths.10 This led to a significant shift in the productive matrix, as Argentina underwent deindustrialization thanks to the increased demand for raw materials and natural resources.11

Figure 4: Percentage of the Participation of the Industry in the GDP of Argentina and China.

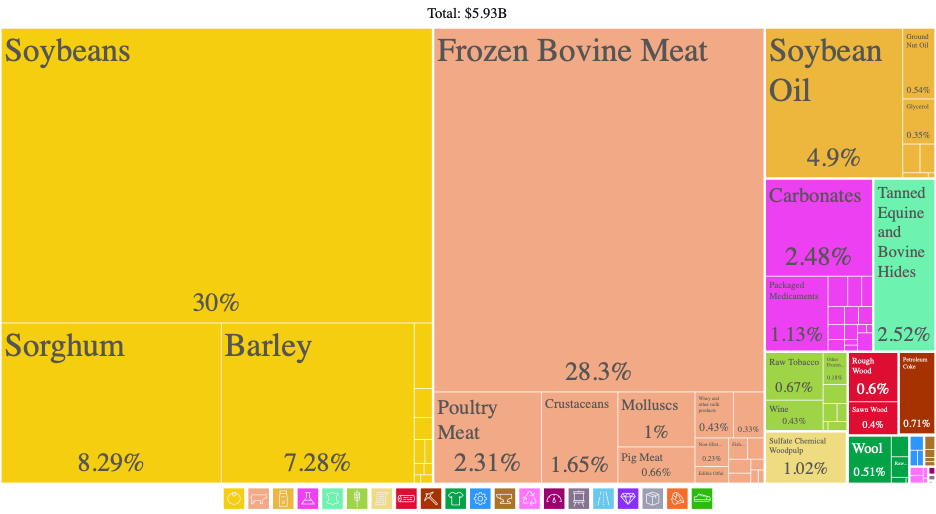

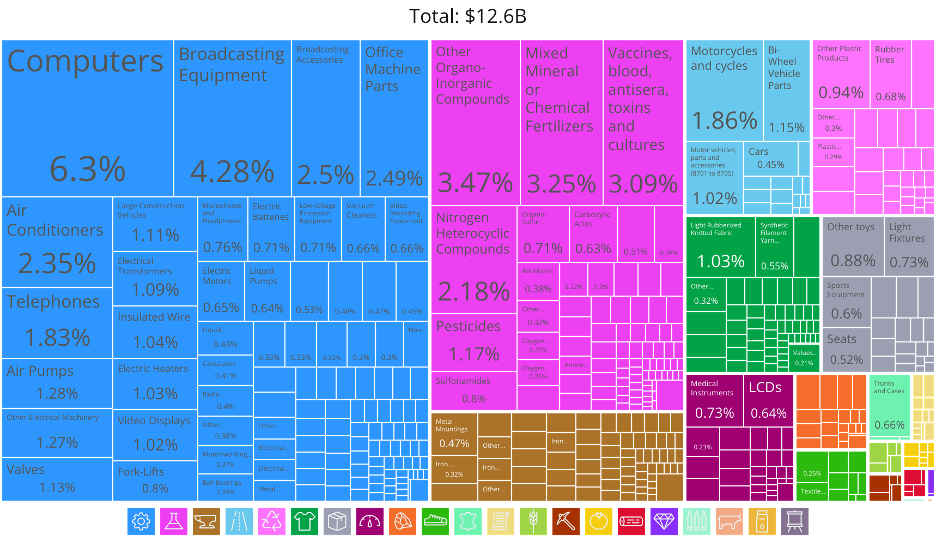

Increased trade with China has only intensified the shift. Soybeans constitute the leading export from Argentina to China, equaling one third of the total. Fulfilling Chinese demand for soybeans has, in turn, entirely transformed the Argentine economic landscape.12 Figures 5 and 6 illustrate the profound imbalance in the diversity of exports and imports between the two countries.

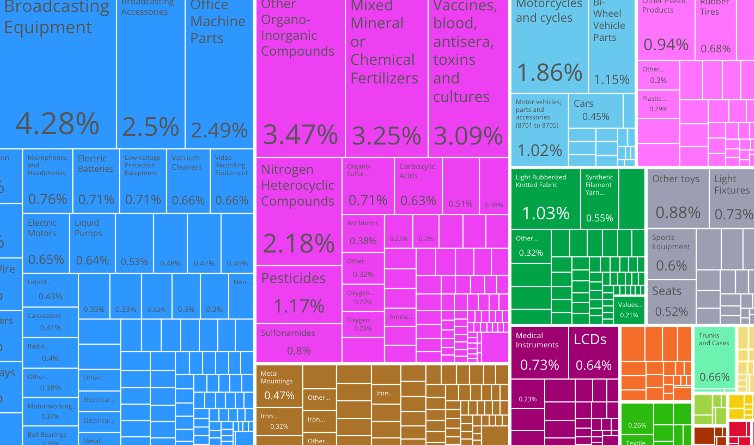

Figure 5: Argentina Exports to China

Figure 6: Argentina Imports from China

Structural constraints

Milei is not the first Argentine leader to resist growing economic ties to China. Since 2015, the Macri administration has aimed to curtail cooperation and emphasize a geopolitical alliance with the United States. But then, too, economic realities forced the government to reverse course. During the first seven months of Mauricio Macri’s government, China reduced soybean imports by 30 percent and soybean oil imports by 97 percent. During the 2016 G20 meeting in China, Macri managed to restore the soybean trade. Because Chinese-financed projects often include a “cross-default” clause that guarantees the cessation of all projects if one is halted, repercussions for pulling back are enormous.

Milei’s orientation towards China, then, is nothing new. Despite its solidifying economic reality, Argentina remains wedded to its alignment with the West. But like administrations before him, Milei will have to come to terms with the changing composition of the global economy: repaying Argentina’s debt to the IMF depends on continued exports to China.

Milei’s failure to find fresh financing from Western lenders may compel his administration to accept Chinese economic diplomacy, leading to a situation similar to Bolsonaro’s administration in Brazil.13 This may result in a strengthened economic reliance on Chinese hands. However, while Brazil is capitalizing on Chinese relations with an important trade surplus, innovation centers, and New Development Bank funds, Argentina will go to China as a “desperate debtor.” China is pressing Milei to confirm that his administration will maintain Chinese interest in Argentina.

Argentina’s case thus brings to light two harsh realities. The first is that Chinese financing and investment across the global South fulfills a structural need rather than a political choice. The second is that, while the emergence of competing superpowers typically opens up opportunities for global South countries, it can also trigger a downward spiral. As is often the case, Argentina stands as an exception, caught in pendular shifts without a clear international strategy.

Jiang, S. (2015) China’s New Leadership and the New Development of China-Latin America Relations, China Quarterly of International Strategic Studies 01, no. 01 (April 1, 2015): 133–53, https://doi.org/10.1142/S2377740015500074; Kevin P. Gallagher, The China Triangle: Latin America’s China Boom and the Fate of the Washington Consensus (Oxford University Press, 2016); Kaplan, S. B. (2021). Globalizing Patient Capital: The Political Economy of Chinese Finance in the Americas. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316856369.

↩American Enterprise Institute (AEI). (2018). China global investment tracker. Retrieved August 23, 2022, from https://goo.gl/e3vs3V.

↩Basualdo, E. Endeudar y fugar: Un análisis de la historia económica argentina, desde Martínez de Hoz hasta Macri (Siglo XXI Editores, 2020).

↩The article VI IMF statute explicitly manifests that: “(a) A member may not use the Fund’s general resources to meet a large or sustained outflow of capital (…) and the Fund may request a member to exercise controls to prevent such use of the general resources of the Fund. If, after receiving such a request, a member fails to exercise appropriate controls, the Fund may declare the member ineligible to use the general resources of the Fund.”

↩Basualdo, 2020; Monteagudo, G. (2022) IMF Holds Argentina Hostage Again, NACLA Report on the Americas 54, no. 4 (October 2, 2022): 365–68, https://doi.org/10.1080/10714839.2022.2145108.

↩Kaplan, S. B. (2021). Globalizing Patient Capital: The Political Economy of Chinese Finance in the Americas. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316856369.

↩Hung, H. F. (2022). The Clash of Empires: From ‘Chimerica’ to the ‘New Cold War.’ Cambridge. https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/clash-of-empires/12211AC3B8957E8DE6C7F26998EB50C3.

↩Kaplan 2021.

↩Weber, I. How China Escaped Shock Therapy (Routledge, 2021).

↩Haro Sly, M.J. y Hurtado, D. (2023) Hacia la convergencia de trayectorias en ciencia y tecnología que se bifurcan: desafíos de la cooperación de Argentina y China. En: Andrés, M.(Ed) Argentina-China. 50 años de Relaciones Diplomáticas. Cooperación, Desarrollo y Futuro. Mincyt y la Academia China de Ciencias Sociales. https://www.argentina.gob.ar/sites/default/files/c_2023-05-08-argentina-china.pdf.

↩Svampa, M. (2013) Consenso de los Commodities’ y lenguajes de valoración en América Latina. Nueva Sociedad No 244, 3-4/2013, www.nuso.org/upload/articulos/3926_1.pdf.

↩Haro Sly, M. The Argentine portion of the soybean commodity chain. Palgrave Commun 3, 17095 (2017). https://www.nature.com/articles/palcomms201795.

↩Kotz, R. L., & Haro Sly, M. J. H. (2022). China’s Economic Diplomacy in the Context of the Far-Right Government’s Neoliberal Nationalism: The Case of Brazil’s Energy Sector. In J. Rajaoson & R. M. M. Edimo (Eds.), New Nationalisms and China’s Belt and Road Initiative (pp. 1-14). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-08526-0_14; Kotz and Haro Sly, 2022; Gonzalo, M., Harfuch, M. P., Haro Sly, M. J., Lavarello, P., & Gonzalo, M. (2023). 5G Kick-off in India and Brazil: InterState Competition, National Systems of Innovation, and Catch-Up Implications for the global South. Seoul Journal of Economics, 36(1). https://ssrn.com/abstract=4372457.

↩

Filed Under