The adoption of fiscal rules has emerged as a global trend over the past four decades. While institutional constraints to fiscal policy were uncommon before the 1990s, recent data indicates that they have since been put in force in more than forty economies. This proliferation reflects a consensus position against the so-called deficit bias—the alleged tendency of governments to run public deficits—which became a priority of fiscal policy management over this period.1 By regulating spending, debt, and fiscal results, rule-based fiscal policy intends to reduce political influence on public expenditure.

In what follows, we take the evolution of fiscal rules in Brazil as a case study to analyze the deeper relationship between the rise of austerity and the spread of fiscal policy constraints. From Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s first tenure as President to the present, a significant shift in rule-based fiscal policy has taken place. In the early 2000s, under the government of Lula’s Workers Party (the Partido dos Trabalhadores, or PT), redistributive growth was achieved through a combination of increased government spending and a near-religious commitment to fiscal rules compliance. But when the financial situation deteriorated during the presidency of Dilma Rousseff, the opportunities for expanding the redistributive policies vanished, and proponents of fiscal responsibility turned furiously against her. After her impeachment in 2016, which put an end to almost fourteen years of PT governments, the new administration introduced a strict spending cap. Since then, Brazil has been through intense and constant austerity. The enduring strength of the discourse around fiscal responsibility is visible today, with a new Lula administration maintaining the legitimacy of fiscal rules in a bid to hold together a fragile Congressional coalition. In light of this history, we argue that fiscal rules ought to constitute a vital arena for political and economic debate in the coming years.

Fiscal arrangements and crisis management

Although there are four main types of fiscal rules—the expenditure rule, debt rule, primary result rule, and revenues rule—combinations of these have produced a significant diversity of fiscal arrangements. Fiscal rules vary not only according to the aims of a given fiscal policy but also their legal status: they can be either constitutional or ordinary laws, subject to domestic or external regulation, and representing a lasting or a medium-term political commitment.2

One reason for this diversity is that fiscal arrangements are spread unevenly across regions, arising from particular conjunctures. Whereas national fiscal rules in the Eurozone were mandated by the Stability and Growth Pact of the 1990s, rule-based fiscal policy in Latin America emerged during the 2000s, following the sovereign debt crises that marked the end of the previous decade. Different structural conditions in developing and developed economies (i.e., level of income, degree of industrial complexity, labor force characteristics, access to technology, and so on) also shape fiscal policy management, determine the enforceability of fiscal rules, and motivate varieties of institutional change.

But in all its variations, the worldwide expansion of fiscal rules was driven by crisis management. In the aftermath of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, policy makers were chiefly concerned with adjusting fiscal arrangements to fit cyclical market behavior and unexpected shocks. The resulting consensus revolved around promoting flexibility (like expanding escape clauses) and enforceability (increasing sanctions and correction mechanisms and introducing independent fiscal councils).3 More recently, several countries suspended their active fiscal rules in 2020 following the Covid-19 pandemic.4 When the emergency was controlled, national debt levels were considerably higher, but efforts to reduce them reflected a shift away from harsh austerity measures and towards “growth-supporting fiscal policies.” In developed economies especially, recent commentators have advocated for arrangements that allow long-term fiscal consolidation without compromising government spending in key areas, such as the green transition.

These experiences demonstrate the incompatibility between the institutional arrangements in force and the economic challenges ahead. While the crisis of 2008 exposed the rigidity of fiscal rules, the pandemic-induced reforms favoring flexibility and enforceability were still not commensurate with needed state activity. The two crisis responses reveal an underlying institutional instability—the assumption that fiscal rules can permanently correspond to their stated goals no longer holds. Fiscal arrangements will change when economic cycles end, unanticipated shocks appear, mainstream discourse is reshaped, or political coalitions reorganize.

But the public debate on rule-based fiscal policy almost exclusively focuses on the design of rules and technical solutions to increase compliance. Neglecting the politically contingent and potentially unstable nature of fiscal arrangements, it promotes a moralizing discourse about fiscal policy, according to which deviant trajectories are to be managed by austerity in both the short and the long term. By enforcing the reputational costs on governments, proponents of fiscal rules expect to reduce the partisan influence on fiscal policy and increase popular support for sound finance.5

Three decades of rule-based fiscal policy in Brazil

Brazil’s rule-based fiscal policy emerged with redemocratization in 1988. In that context, a new constitutional Golden Rule prohibited issuing debt to pay current expenses and reserved it for new investments, whose costs could be distributed over time as returns come in.6 However, the effective consolidation of modern fiscal management only occurred in 2000, when a supplementary measure called the Fiscal Responsibility Law (Lei de Responsabilidade Fiscal, LRF) established limitations on spending and debt trajectories.7

The origins of the LFR lie in the 1994 Plano Real—an ingenious price stabilization program that ended years of inflationary pressures.8 As the Plan relied on an exchange rate anchor that sustained parity with the US dollar, it led the Brazilian Central Bank to pursue high interest rates, and consequently to higher budget deficits: between 1995 and 2002, interest payments averaged 7.2 percent of GDP.9 However, liquidity shocks caused by the Mexican, Asian, and Russian crises of the 1990s ultimately rendered this currency anchor unsustainable.

Like other Latin American economies, Brazil’s alternative measure for inflation control was based on the “macroeconomic tripod”: the floating exchange rate regime, inflation targeting,10 and establishment fiscal targets as part of a Fiscal Stabilization Program signed with the IMF.11 The arrangement made fiscal surpluses necessary to control public debt resulting from above-average real interest rates.12 The tripod was expected to promote inflation control, balance of payment equilibrium, and public debt stability in the medium run. Price stabilization, therefore, is at the origins of the rule-based fiscal policy in Brazil.

Given the dependence on export revenues and foreign capital inflows, Brazil (and other Latin American countries) have always been sensitive to boom and busts in the global economy. When the latter experiences exceptional growth, it is likely that the former will have additional room for fiscal intervention. By contrast, when global economic trends recede, developing economies are exposed to liquidity shocks, an increased risk of balance of payment crises, and weakened capacity for tax collection and revenue generation. These changes, in turn, can affect fiscal rules compliance.

The early 2000s Latin American commodities boom opened space for a collective shift towards increased public spending and redistributive social policies. But as fiscal outcomes deteriorated after 2011, this Pink Tide receded along with the commodity boom. Governments across the region either abandoned or modified rules to assure compliance with their fiscal restraints, with many sidelining redistributional policies.

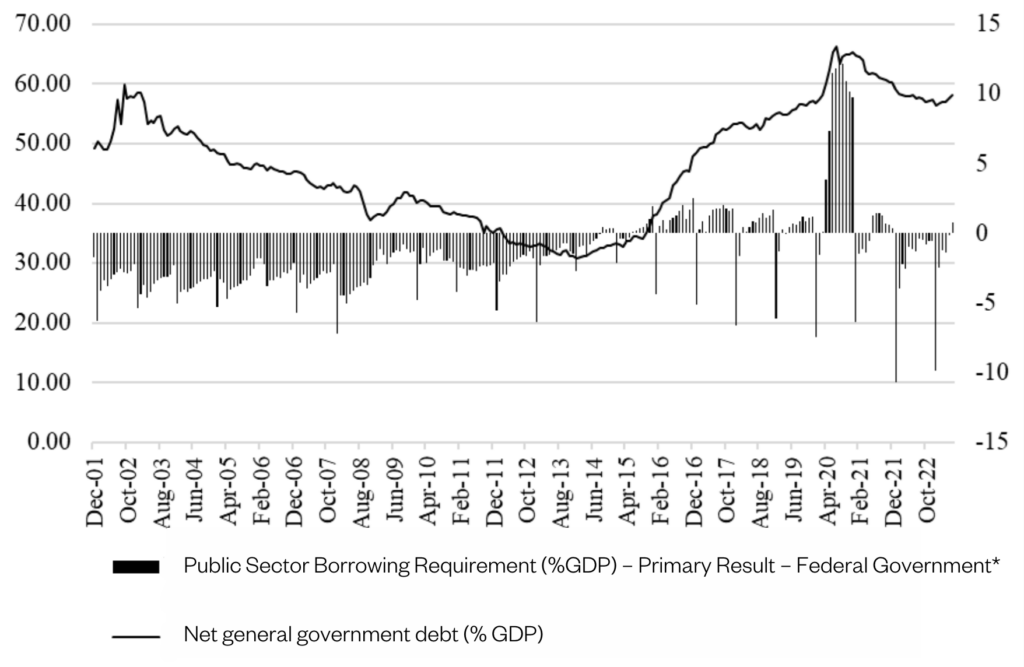

In Brazil, the LRF was initiated a few years before the commodities boom and, from the early 2000s to the mid-2010s, it proved to be quite successful in meeting its objectives. The chart below shows that fiscal surpluses were maintained and the debt-GDP ratio dwindled. The inflation rate also remained stable despite a consistent fall in the policy interest rate. Finally, the Brazilian exchange rate appreciated considerably during the period and contributed to controlling inflation.13 Perhaps the most interesting trend was the significant increase in primary government expenditures, from 15 percent to 19.5 percent of GDP in the 2003–2015 period, without compromising the LRF.

Source: Brazilian Central Bank Data. *The PSBR series is displayed on the secondary axis and shows the accumulated flux during the year.

Following the election of the PT candidate in 2002, Lula da Silva’s government (2003–2009) promoted a large increase in social spending and public investment.14 Besides the growing revenues associated with the booming phase of the cycle, another important factor allowing for increased expenditure was the ability of Lula’s governments to enact policy alternatives and institutional development that directly and indirectly affected public spending. Social policy, for example, was significantly boosted by the rising value of the real minimum wage—to which the former was anchored by a constitutional rule. In addition, the government actively encouraged the creation of formal jobs, which expanded access to social benefits.15 The government also managed to remove capital expenditures from the surplus requirements of the LRF, which enabled greater state-led investment, including for public companies.16 Finally, fiscal space was used to increase social provisions with public health and education, which are, as recent studies have indicated, important drivers of inequality reduction in Brazil.17 In Brazil, then, the commodities boom reduced external fragility concerning the balance of payments vulnerabilities and amplified fiscal space for the government to foster domestic demand.18

But by 2013 the situation had deteriorated. When Dilma Rousseff succeeded Lula in 2011, inflation showed signs of increase even with the appreciated exchange rate, leading the government to raise the primary surplus from 2 percent in 2010 to 2.14 percent in 2011. In 2012, with the slowdown in both domestic and external demand, the government decided to substitute expenditure-led fiscal expansion with tax exemption measures that did not generate the expected dynamism and simply contributed to a fall in public revenues.19 Moreover, it opted to employ poorly-communicated accounting practices that led the opposition and the media to question the real ability of the government to commit to fiscal responsibilities.20

The combination of lower growth rates, increasing tax exemptions, and the larger share of GDP dedicated to public spending strained the utility of the LRF. Indeed, as the first primary deficit of the PT era occurred in 2014, the debt-to-GDP ratio increased. The coalition between finance, industry, and the party ruptured. The fast-spreading political opposition to the PT was expressed as fear of an uncontrollable debt-to-GDP spiral.

This was a critical moment of distributive conflict in Brazil. After years of increase, the wage-income share reverted its trajectory in the 2014–2016 period, following a profit squeeze. Political realignment toward fiscal austerity coincided with the intensification of distributive tensions between capital and labor in the anticipated Kaleckian fashion—with economic elites reacting to the rising power of the working class.21 Facing political turbulence among her governing coalition and growing public dissatisfaction, Rousseff’s government drastically changed the orientation of fiscal policy towards austerity in line with the LRF. But the image of the government’s fiscal irresponsibility had been established. Dilma was impeached in 2016, ending the PT era.

The most emblematic measure taken by the center-right government that came to power after Dilma’s impeachment was on fiscal policy management. In 2016, inaugurating an unprecedented fiscal arrangement, Brazil approved a constitutional measure (the so-called teto de gastos, or “expenditure ceiling”) that froze real spending growth for twenty years, limiting the adjustments of expenditure by the previous year’s inflation (measured according to the Extended National Consumer Price Index, IPCA). The strictness of the ceiling contrasted with the possibilities embedded in the LRF. First, fiscal surpluses were divorced from public spending, even in the case of a booming economy and growing revenues. Second, a no-real growth limit halted the institutional channels that fostered public spending expansion during the 2000s. Third, any GDP increase would mean a decrease in government expenditures as a share of GDP and per capita terms, indicating an opposite trajectory from that which characterized the previous period.

The teto de gastos aimed to reduce state activity in Brazil. In order to preserve essential expenditures, future governments would be forced to reallocate resources and leave important areas uncovered. The most affected area of these cuts was public investment, which had been losing relative importance in total expenditures since the interruption of the PT government. The fiscal rules reform of 2016 can thus also be seen as a response to the intensification of the distributive conflict.

From 2017 onwards, the Brazilian fiscal arrangement included the Golden Rule, the LRF, and the teto de gastos. In theory, these would complement each other to form a functional fiscal framework. But in practice, they were contradictory rules with different objectives—in which the last one clearly became dominant.22

The arrangement based on the teto de gastos eroded rapidly. Already in 2019, exceptions to increase expenditure above the limit were needed. In the following year, with the Covid-19 pandemic, the rule had to be bypassed again through an emergency budget that allowed the government to spend in order to minimize some of the pandemic impacts. Finally, prior to the 2022 elections, a growing consensus around a new fiscal arrangement emerged. Lula’s platform positioned a new fiscal arrangement as a key priority for 2023. Back in power, he presented an official proposal on March 30th.

New moment, new rule

The new fiscal arrangement proposed by the current Lula government and approved by Congress is called the “Sustainable Fiscal Regime” (SFR). In contrast with the teto de gastos, the SFR employs the design of standard fiscal rules used by other countries—a revenue rule, an expenditure rule, and a primary result target—but organizes them in a particular fashion. First, the primary result target is not a single value (as it was in the LRF) but limited to a range of +0.25 and -0.25 percentage points of a central target. Second, primary expenditures are now allowed to grow in real terms, up to 70 percent of the growth rate of the previous period’s revenues. Here, the primary result target is also important: if the result remains below the lower bound of the target range, the expenditures’ growth rate is limited to 50 percent of the revenues’ growth rate. In that case, other triggers that mainly restrict mandatory expenditures are put in place.23

This mechanism is designed to maintain a primary surplus. An additional layer of spending control is offered by the expenditure rule, which introduces a countercyclical mechanism of an upper and lower bound to the expenditure growth, avoiding rapid drops or rises if revenues vary greatly. In this way, spending is also conditioned by an interval that defines its real growth rate: it cannot grow less than 0.6 percent or more than 2.5 percent. Finally, the SFR establishes new parameters to guarantee space for public investments in the budget. First, it determines an “investment minimum” of 0.6 percent of the previous year’s GDP (in real terms). Second, in the case of primary surpluses above the upper limit of the primary result target range, 70 percent of the “surplus excess” can be used as an investment in the following year without entering the primary result calculation. However, this allocation is limited to 0.25 percent of GDP.

The SFR entails several improvements compared to the previous arrangement, the foremost being that it assures real growth in government spending. Also, it establishes a countercyclical mechanism that smooths spending following boom and busts, which was absent even in the LRF. Another highlight is the stipulation of the “investment minimum” and the investment from “surplus excess,” which can not only help recover an expenditure category that has been sharply reduced but also assure a space for investment in the budget—even though its implementation may still be constrained if revenues are lower than expected, risking the achievement of the primary goal. Finally and significantly, the SFR is not included in Brazil’s constitution, which means it can be adapted to changes in the conjuncture.

But the SFR continues to be restrictive for a country that needs the expansion of the public sector to guarantee basic rights and foster economic growth. The constitution states that at least 15 percent of current net revenue should be used for public health and 18 percent of revenues from taxes for education. Further, unemployment benefits and other transfers are linked to the minimum wage—and expenses related to the pension system are likely to increase with an aging population. However, the new fiscal rule operates with a logic of expenditure growing less than tax revenues and results in a reduction of the size of the state as a proportion of GDP.24 The maintenance of social benefits and public services are likely to be in conflict for space in the budget, leaving doubts about the viability of the public investments.25 In other words, if the rule is maintained in the future, the government will likely have to choose between the value and size of existing social programs, the provision of public health and education, and the capacity to invest. In a developing country with enormous inequalities and aspirations to green development, the SFR should be subject to urgent debate.

It is important to understand the political context in which the SFR was proposed. Lula is back in Brazil’s presidency after four years of Jair Bolsonaro’s far-right government, which still holds strong popular support. Victory in the 2022 election demanded that the PT form a large and politically diverse coalition, and turnover in the Congress was less dramatic than expected. With thin margins of support, Lula’s administration will face significant challenges in governance.

Despite the failure of the teto de gastos, the fiscal policy debate remains dominated by pro-austerity orthodoxy—something Lula himself complained about in the first months of 2023.26 In this context, the SFR limits should be seen as the price to pay for its approval. In any case, Lula’s government has won some battles, preserving minimum wage raises from SFR’s non-compliance triggers, and ensuring that external donations (such as the Amazon Fund) would not be subjected to the rule.

Whether the new fiscal arrangement will show compliance without compromising the economic and social demands of a large developing economy such as Brazil remains to be seen. However, because of the aforementioned reasons, a large expansion of government spending of the kind that occurred during the 2000s appears impossible under the SFR. More than that, the government will have to readapt fiscal policy to fit into the new institutional framework. It implies removing legal mechanisms that have not only contributed to reducing Brazil’s poverty and inequality levels via public spending but also protected key areas from cuts under the expenditure ceiling (i.e., minimum commitments concerning public health and education). Once these legal assurances are lifted, it becomes difficult to backtrack, especially considering the neoliberal trends that define the contemporary relationship between states and markets.

That Lula and PT proposed the SFR reveals the political aspect of these technical debates. Political convergence against non-real spending growth was forged, but fell short of reinstating the previous conditions for expenditure growth. During the 2000s, Lula enjoyed favorable conditions that facilitated redistribution via public spending in line with the prior LRF. In the new consensus represented by the SFR, there is tighter restraint on expenditures, even in the case of bonanza periods, which limits the government ability to participate in the long-run growth plan—central to the PT’s old growth strategy—ceding ground to the private sector. The foundations of the rule-based fiscal policy lie in removing political control from national budget management.

It is unfortunate, then, that the debate around the SFR has been focused on its technical aspects, not the type and size of the state provision necessary for Brazil social and economic development. In hurriedly adapting its rule-based fiscal policy to international technical standards, the PT government might have also increased the barriers to redistributive growth by reducing fiscal policy—and the public debates over its purpose—to the need to tame instabilities through automatic stabilizers.

Fiscal policy can help resume economic activity and maintain social stability—a precondition and ultimate policy aim of a social democratic pact. But when rigid and ostensibly apolitical fiscal rules moralize the public spending debate in favor of sound finance, responding to changing economic conditions with blunt compliance mechanisms, such a path cannot be pursued. As the Brazilian case suggests, a careful analysis of the institutional changes in fiscal arrangements can bring light to the conflictual nature of the rule-based fiscal policy. Fiscal rules claim to insulate fiscal policy from political influence. But this is its own form of politics: constraints reduce the space for the working class, whenever in power, to influence fiscal policy decisions and pursue redistribution.

According to the dominant literature, the growth of public deficits results from profligate governments leaving fiscal control to future policymakers, or from the capture of group interests pursuing electorally beneficial spending programs. See: Wyplosz, Charles. 2013. “Fiscal Rules: Theoretical Issues and Historical Experiences.” In: Alesina, Alberto., and Giavazzi, Francesco. (Eds.) Fiscal Policy after the Financial Crisis, University of Chicago Press, pp. 495-525

↩Lledó, Victor, Yoon, Sungwook., Fang, Xiangming. Mbaye, Samba. and Kim, Young. Fiscal Rules at a Glance. International Monetary Fund, 2017.

↩Eyraud, Luc., Debrun, Xavier., Hodge, Andrew., Lledó, Victor., and Patillo, Catherine. “Second-Generation Fiscal Rules: Balancing Simplicity, Flexibility and Enforceability.” IMF Staff Discussion Note, SDN 18/04, International Monetary Fund, 2018.

↩Davoodi, Hamid R., Elger, Paul., Fotiou, Alexandra., Garcia-Macia, Daniel., Han, Xuehui., Lagerborg, Andressa., Lam, W.Raphael., and Medas, Paulo. “Fiscal Rules and Fiscal Councils: Recent Trends and Performance during the COVID-19 Pandemic.” IMF Working Paper No. 2022/011, International Monetary Fund, 2022.

↩Debrun, Xavier. and Jonung, Lars. 2019. “Under threat: Rules-based fiscal policy and how to preserve it.” European Journal of Political Economy, 57 (2019), pp. 142-157.

↩A consequence of the Golden Rule is the obligation that every new current expense created must have its own source of tax collection, linking the maintenance costs of the State with its tax revenue capacity. However, its application does not guarantee debt sustainability. See: Pires, Manoel. “Uma análise da regra de ouro no Brasil,” Brazilian Journal of Political Economy, 39(1), 2019, pp.39-50.

↩The ratio of net public debt-to-net revenues cannot exceed 3.5 for the federal government, 2 for states and 1.2 for municipalities and there are maximum limits on personnel expenditure, as a proportion of net current revenues (federal: 50%, states: 60% and municipalities: 60%) and include both active and retired public servants. See: Berganza, Juan Carlos. 2012. “Fiscal rules in Latin America: a survey,” Banco de España occasional paper.

↩The Real Plan (Plano Real) was a set of economic reforms that took place in 1994, with the aim to bring macroeconomic stability and end hyperinflation. The plan was divided into three phases, the Fiscal Adjustment, Deindexation and Nominal Anchor (which corresponds to the launch of the real as the official currency in Brazil, anchored to the dollar).

↩Giambiagi, Fabio., and Ronci, Marcio. “Fiscal policy and debt sustainability: Cardoso’s Brazil, 1995-2002,” IMF Working Paper, WP/04/156, 2004.

↩Bogdansky, Joel. Tombini, Alexandre A., Werlang, Sergio R. da Costa. “Implementing inflation targeting in Brazil,” Working Paper Series no.1, Brasilia, Central Bank of Brazil, 2000.

↩Nassif, André., Feijó, Carmem., Araújo, Eliane. “Macroeconomic policies in Brazil before and after the 2008 global financial crisis: Brazilian policy-makers still trapped in the New Macroeconomic Consensus guidelines.”Cambridge Journal of Economics, 44(4), 2020, pp. 749-779.

↩Barbosa, Nelson. “Inflation targeting in Brazil: 1999-2006,” International Review of Applied Economics, vol.22, no. 2, March 2008, 187-200.

↩Summa, Ricardo. Serrano, Franklin. “Distribution and Conflict Inflation in Brazil under Inflation Targeting 1999-2014.” Review of Radical Political Economics, 50(2), 2018, pp.349-369.

↩A significant part of it was due to increasing social benefits focused on low-income households, such as the emblematic Bolsa Familia. Public investment surged especially between 2005 and 2009, public investment surged (its average accumulated growth reached almost 25 percent).

↩For a debate on Latin American welfare regimes, see: Barrientos, Armando. 2009. “Labor markets and the (hyphenated) welfare regime in Latin America,” Economy and Society, 38(1), pp. 87-108.

↩Serrano, Franklin., and Summa, Ricardo. 2015. “Aggregate demand and the slowdown of Brazilian economic growth in 2011-2014,” Nova Economia, 25(s.n), pp. 803-833.

↩Silveira, Fernando G. and Palomo, Theo R. “The Brazilian State’s Redistributive Role: Changes and Persistence Throughout the 21st Century,” Discussion paper n.275. Ipea – Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada, 2023.

↩Loureiro, Pedro M. “Reformism, Class Conciliation and the Pink Tide: Material Gains and Their Limits.” In Ystanes, M., & Strønen, I. Å. (Eds.). The Social Life of Economic Inequalities in Contemporary Latin America, 2018, Springer International Publishing.

↩Chernavsky, Emilio., Dweck, Esther., Teixeira, Rodrigo A. “Descontrole ou inflexão? Política Fiscal do governo Dilma e a crise econômica,” Economia e Sociedade, 29(3), 2020, pp.811-834.

↩Orair, Rodrigo., and Gobetti, Sergio. “Brazilian Fiscal Policy in Perspective: From Expansion to Austerity.“ In Arestis, Philip., Baltar, Carolina., Prates, Daniela. (Eds.). The Brazilian Economy since the Great Financial Crisis of 2007/2008, 2021, Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 219–244.

↩Martins, Guilherme Klein., and Rugitsky, Fernando. “The Long Expansion and the Profit Squeeze: Output and Profit Cycles in Brazil (1996–2016),” Review of Radical Political Economics, 53(3), 2021, 373–397. See also: Marques, Pedro Romero, and Rugitsky, Fernando, “Rentiers and distributive conflict in Brazil (2000-2019),” Cambridge Journal of Economics, forthcoming.

↩Previous work has explored the particularities of Brazilian fiscal rules: Marques, Pedro Romero., Rodrigues, Lucca Henrique., Serra, Gustavo., and Cardoso, Dante. “Regras fiscais no Brasil e no mundo: o que é preciso saber antes da nova proposta do governo?” Nota nº 035, 2023, Made/USP.

↩It prohibits the creation or readjustment above inflation of mandatory expenses, hiring and holding public tenders, the readjustment of public employee salaries, the expansion of subsidies or tax incentives, among others. Fiscal impacts arising from minimum wage increases, however, are shielded from these triggers.

↩In simulations, total expenditures as a share of GDP decrease in all scenarios considered, with the optimistic scenario (the one with higher GDP growth) being the one where the decrease is more pronounced. This occurs even considering the potential impact of public investment multipliers on GDP growth, revenues increase and subsequent increase in government spending. See: Marques, Pedro Romero. Brenck, Clara Zanon., Carvalho, Laura. Rodrigues, Lucca H., Gomes, João Pedro de Freitas. “Quais os efeitos do novo arcabouço fiscal sobre a trajetória de gastos públicos? Uma análise preliminar” Nota nº 036, 2023, Made/USP. See also: Brenck, Clara Zanon., Marques, Pedro Romero., Lima, Gilberto Tadeu; Rodrigues, Lucca Henrique G.; Sanches, Marina da Silva; Cardoso, Dante; Serra, Gustavo, “Considerações sobre o regime fiscal sustentável e a importância do investimento público para seu funcionamento,” Nota nº 042, 2023, Made/USP.

↩The fiscal rule establishes a minimum for investment when planning the budget. That does not mean, however, that the investment will be fully executed as planned.

↩See: Marques, Pedro Romero, “O motivo da indignação fiscal de Lula (ou, por que se tornou mais difícil aumentar o salário mínimo no Brasil?).” Nota nº 032, 2023, Made-USP.

↩

Filed Under