Negotiations at the Summit for a Global Finance Pact in Paris last week took place between fifty heads of state. They revolved around how poor countries might develop and decarbonize, within the confines of the existing financial system. A common refrain was that the rules of the international order were laid down during World War Two, when many of the countries present had not yet decolonized and won independence. “A new financial architecture” must be created, Kenyan president William Ruto bluntly told Macron and World Bank and IMF heads, “where governance and power is not in the hands of a few.” “Many of our countries lack the necessary fiscal room to take on additional debt,” he added.

Ruto was not concerned with where the US or EU would find the money; their financing constraints are ideological and political compared to the hard structural barriers faced by Kenya and peers. Even if it was light on concrete fixes, the summit negotiations highlighted that the “non-regime” of global finance favors the big shareholders of the Bretton Woods Institutions, and constricts both economic development and cutting emissions.

| Problem | Solution | Instrument within EU | Negotiations between North-South |

| Cost of borrowing is too high | Central bank should purchase country’s debt if its borrowing costs rise because of excessive risk avoidance by investors | ECB bond purchases (PEPP, Transmission Protection Instrument) | Foreign exchange guarantee (Persaud); Credit ratings agency reform (Ruto) |

| Companies in rich countries get more subsidies than those in poor countries | Compensate firms in poor countries | Sovereignty Fund (now STEPS) | IMF reform; shipping taxes; wealth taxes (Summit for a New Global Financing Pact Roadmap) |

Europe is in a similar predicament. Drought has disrupted firms, farms, and families across the continent. Investment has fallen off the pre-pandemic and war trend. Technically (though employment has never been higher) it is in a recession midway into 2023. Interest rates are slated to rise further. Where will the continent find the trillions of euros for its green transition?

Taxes and borrowing are two options. But new taxes in the EU require unanimous support of the 27 member countries to become law. That’s when things become tricky. Here is how the conversation usually goes. Let’s say you want a wealth tax on super rich, tax-avoiding corporations: try getting a yes vote from the havens of Ireland, Netherlands, and Luxembourg. A tax on nitrogen? Dutch farmers are in rebellion. How about a tax on the incredibly dirty marine diesel that ships use? Shipping merchants in Greece. A tax on heavy industry? Opposed by Poland and Czech Republic. A minimum tax on corporations? Poland again. A higher tax on petrol? Have you heard of France’s Yellow Vest movement? Can we tax the commodity traders that have made a fortune off the war? Good luck with Switzerland. So can we try borrowing instead? Welcome to the fiscal rules debate.

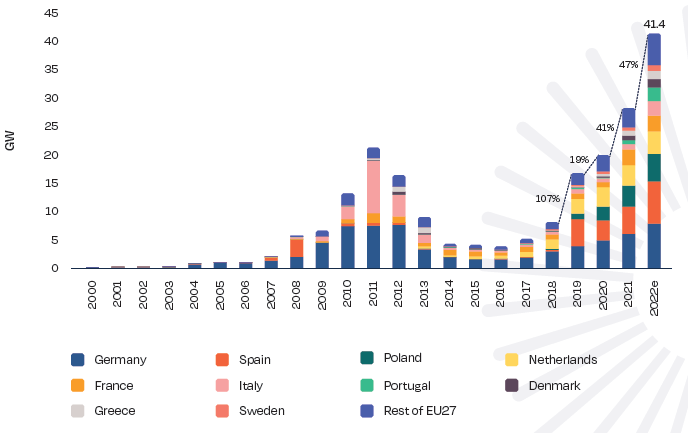

To understand why the choice of macroeconomic policy determines countries’ ability to go green, look at what happened to green investments during the Eurozone’s ruinous 2010s austerity policy. Solar panel installations dropped off a cliff in Germany, Italy, Greece, Spain and more, as the Eurozone wrongheadedly pursued macroeconomic policy of austerity. Politically, the EU was just as climate-friendly as it is today, but seven years of green investment were lost—which it now has to regain in the 2020s.

Everyone now recognizes that green investment will create jobs, cut emissions, and provide more security. It also involves up-front capital costs. The EU has done the sums. Meeting the target of 55 percent emissions cuts by 2030 (compared to 1990 levels) requires further investment of about 2 percent of GDP in total each year for transport, homes, and electricity. The EU committed to enhanced Fit for 55 (2030) targets in 2022. What it now needs to find are funds, which means letting go of old ideas about fiscal responsibility.

Public expenditure in European countries is closely monitored by the Commission as a condition of EU membership.

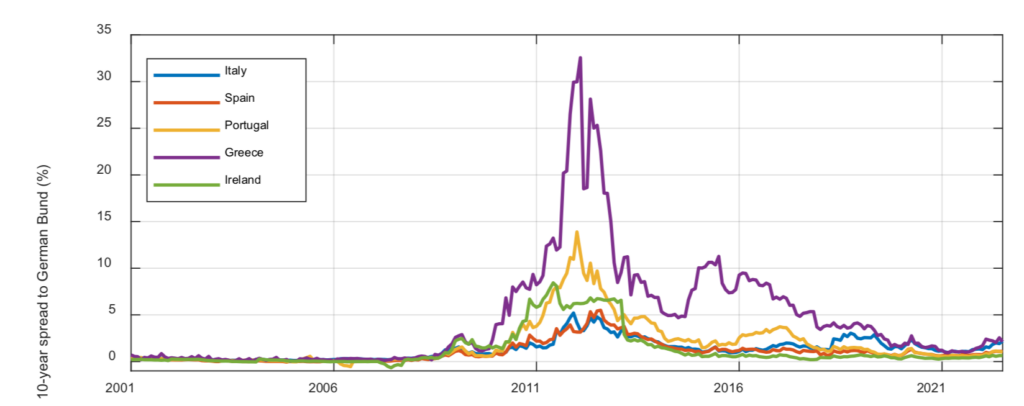

Kenya is shut out from the markets, with most of its external debt owed to China and multilateral development banks. (African countries are currently borrowing at obscenely expensive rates of up to 20 percent.) Ruto has pushed for reform of Western credit rating agencies and accused them of a bias against African countries that substantially increases their cost of borrowing. Most European countries can borrow money from debt markets at less than 4 percent; for Germany, it’s closer to 2 percent.

Europe constrains its ability to use this relatively cheap finance. Under the 1992 Maastricht Treaty and the 1997 Stability and Growth Pact, the fiscal movements of EU members are monitored for signs of exceeding prescribed ratios: 3 percent deficit to GDP, and 60 percent debt to GDP. Those ratios have no deep empirical basis, but reflect a combination of the average debt-to-GDP ratio of the twelve countries negotiating EU rules in 1992, and the deficit ratio at which that debt would stabilize under 1990s growth rates. The rules proved to be too restrictive, throwing many countries into disciplinary processes, and have been revised five times.

A sixth revision is now under way, but the rules have been suspended since 2020, first due to Covid, and then due to energy shock due to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Inflation has since soared, strengthening the hands of fiscal hawks in the European Central Bank. Germany plus the “frugal four” coalition of Netherlands, Denmark, Austria and Sweden that oppose deficits and debt have also gained power. Fiscal rules come back into effect in January 2024, at which point many countries will have to make difficult decisions in order to comply with them.

Shrinking fiscal space

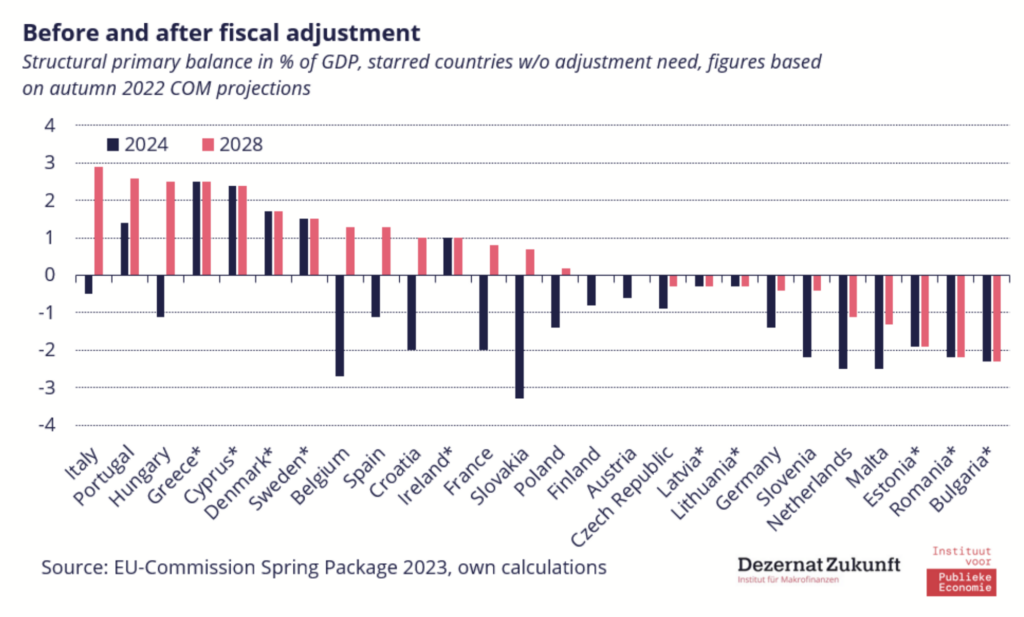

It’s difficult to know exactly what the effect of the new fiscal rules will be on EU countries, because it relies upon projections of growth, expenditure, and interest rates over several years. But if the fiscal rules are to be strictly followed, a lot of the bloc is going to be undertaking fiscal consolidation.

IMF projections analyzed by Zsolt Darvas at Bruegel suggest that when the rules come into force in 2024, seven countries would be subject to discipline under the proposed new rules and a further nine would likely have to reduce their deficits to avoid a procedure. Of the remaining 11 countries, six of them will consolidate anyway, by 1 percent to 3.5 percent of their GDP between 2023 and 2028.

The shrinking of fiscal space is sharper still if budget allocations are assumed to meet the EU’s own climate targets. Philippa Sigl-Glöckner, an economist formerly in Germany’s finance ministry, remarks, “We have it upside down at the moment: Debt to GDP is constrained, and CO2 emissions are not. Fiscal policy, the whole financial and monetary system, should always follow our societal goals—that’s what it’s there for. And for some reason, we’ve managed to flip this around.”

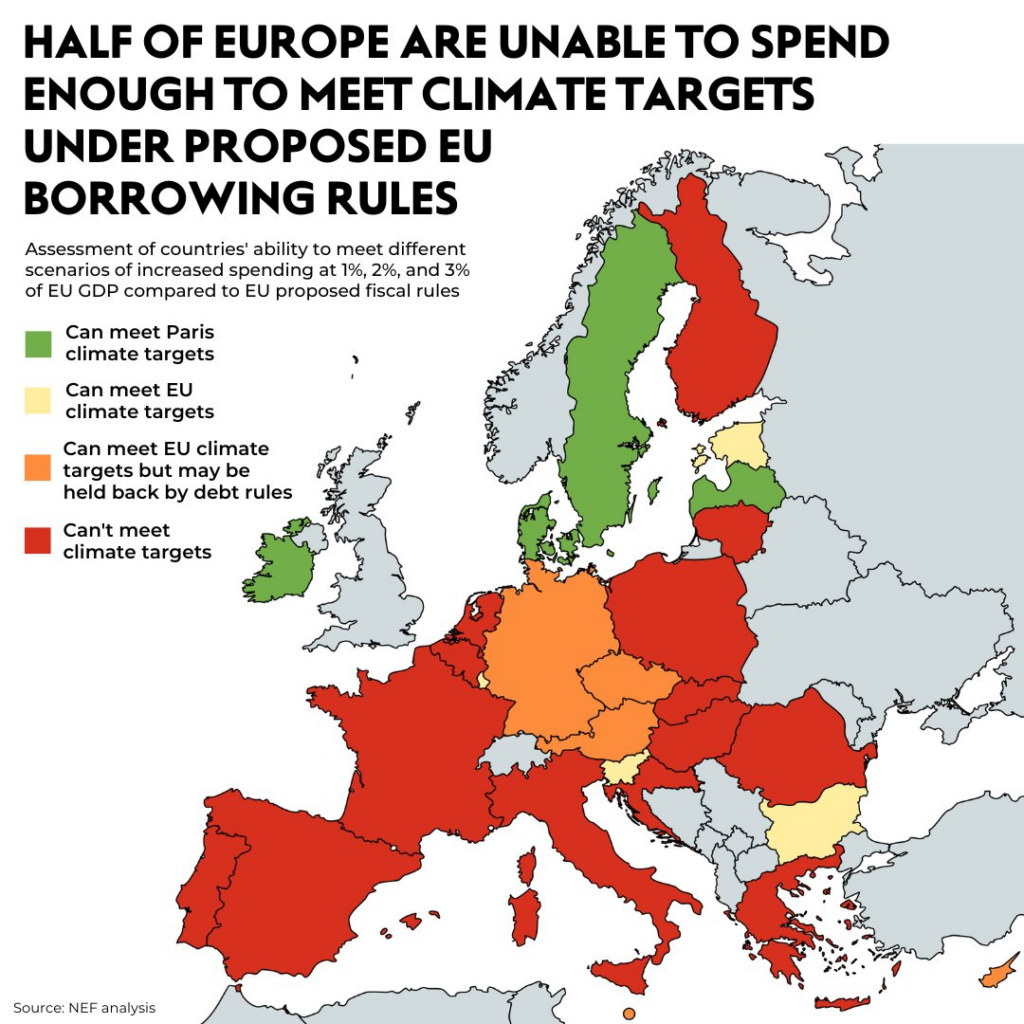

NEF research finds only Ireland, Sweden, Latvia, and Denmark would be able to to practically undertake a 1.5 degree-aligned scenario within debt and deficit limits.” A further five could meet the EU’s own targets (which are less than 1.5C aligned). Another five, including Germany, could potentially meet the low end of the investment required for EU’s climate targets but at risk of triggering EU sanctions for being at medium debt risk, while eight countries including France and Spain would certainly breach the 60 percent debt-to-GDP threshold, according to NEF’s calculations.

The current (suspended) iteration of EU fiscal rules assessed countries’ compliance and performance using complex, assumption-heavy projections, including whether the country is meeting its potential economic output. Sanctions are politically negotiated. The proposed new framework removes both complexity and flexibility. It applies a more rigid application of the 60 percent and 3 percent rules; the most transgressive countries would have to cut their expenditure by at least 0.5 percent of GDP per year.

One of the key tools under the proposed new system is the “debt sustainability analysis,” a forward-looking projection used to determine how rapidly fiscal consolidation has to take place. It allows a degree of discretion and judgment, but it also buys heavily into a fundamental problem: hard ratios of debt and deficits to GDP can be self-defeating because austerity measures tend to shrink the denominator: growth.

The current proposal is still too lax according to Germany, whose liberal finance minister Christian Lindner is pushing for more rigidly and broadly enforced austerity: including requiring an annual minimum reduction of 0.5 percentage points per year even on countries with only moderate debt challenges. Bruno le Maire, his counterpart from France—which was subject to an “Excessive Deficit Procedure” disciplining program for almost a decade from 2009—says such numerical rules risk repeating the sustained mistakes that followed the financial crisis. “We tried in the past to have automatic and uniform rules and it led to recession and economic hardship.”

Could a carve out be made for green expenditures? A fudge for EU’s green deal? Nein. Countries with both excessive deficits and greater than 60 percent debt-to-GDP ratios won’t qualify for that consideration.

Without such a requirement, the discretion to choose how to spend a narrowing budget is unlikely to favor green investments. Faced with constraints, writes Darvas in the Bruegel report, politicians “prefer cutting investment over current spending and unpopular tax increases, partly because the interests of future generations have less electoral support.”

With no hard requirements to prioritize green investment, what will European countries do?

Common funding

While discussions in Paris focused on finance for the developing world, the European Commission unveiled its proposal for a “Sovereignty Fund.” When state aid restrictions were lifted after the war, countries rushed to subsidize their national champions. Firms in countries with big pockets like Germany and France gained at the expense of others. Berlin and Paris together grabbed 77 percent of the €672 billion approved state aid exemptions. The Sovereignty Fund’s goal is to compensate those countries that don’t have the fiscal space to give generous subsidies to their firms and avoid deindustrialization.

But the common fund, unveiled last week, was meager, amounting to only €10 billion. Why wasn’t it bigger? Once again, raising new joint EU debt was opposed by Germany. And instead of being used to deploy existing technologies, a la IRA, the monies are channeled to frontier technologies like chips, hydrogen, and biotech. To get a bigger pot, it now aims at leveraging private finance; optimistic when the EU still lacks a unified capital market.

Fiscal rules and austerity will politically undermine the EU, already in a technical recession. A recent paper on voting patterns finds that the “main economic explanation behind the populist vote in Europe is the economic performance of the region, measured as annual regional growth in GDP per capita.” Center-left and center-right parties risk being swept away as they have in recent elections in Italy, Spain, Austria, and Greece.

In theory, there’s space to throw off ideological constraints, but with inflation the grip of fiscal hawks has tightened. No one should be shocked by a far right wave across the continent that will threaten each objective: climate, transfers within the Eurozone, and North-South solidarity. To riff on the New Yorker cartoon: “Yes, the planet got destroyed. But for a beautiful moment in time we ran deficit-neutral budgets.”

Filed Under