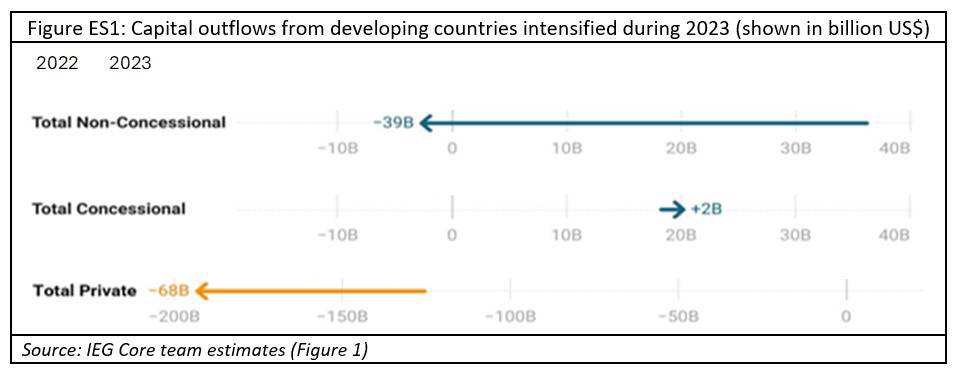

We live in a dysfunctional system in which money flows out of the countries that need it most and into the coffers of the wealthiest. In 2023, the private sector collected $68 billion more in interest and principal repayments than it lent to the developing world. International financial institutions and assistance agencies extracted another $40 billion, while net concessional assistance from international financial institutions was only $2 billion—even as famine spread. The result is that as developing economies make exorbitant interest payments to their creditors, they are forced to cut spending on health, education, and infrastructure at home. Half of the world’s poorest countries are now poorer than they were before the pandemic.

At The Polycrisis we have been tracking the whipsaw of the global financial system amid private finance mantras, interest-rate hikes at the Fed, and the explosion of debt in the global South. In our dispatches on IMF meetings, the Paris conference on debt and climate, the BRICS summit, Barbados, Brussels, Ukraine, and Pakistan, we have sought to throw light on the political economy of financial distress. Who is in need? What do they get from whom, and under what conditions?

The polycentric financial “order”

The World Bank boosted its lending in the wake of the Covid pandemic, but is still well short of meeting the financing needs of developing countries. At the Spring meetings of the IMF and World Bank this week, the question of who adds capital for development, climate resilience, and the energy transition is high on the agenda.

Long-term finance is one thing, but in a crisis, it’s liquidity that counts most—and it can be key to warding off the kind of panic that drives investment away.

In all this, the dollar remains king. Want to make payments? Send an invoice? Store your wealth? Borrow across borders? Chatter about any replacement of the dollar as the dominant reserve currency is overblown. No other contender is willing to run the current-account deficit necessary to be a global reserve issuer. And when a storm arrives, liquidity flows to those with “safe assets” closest to the imperial core, while the burden of “structural adjustment” falls on the poorest and weakest shoulders in each society.

But even so, with US spending stymied by domestic politics, a new set of global players is fronting the cash for states in need of liquidity. Something resembling a polycentric financial patchwork has slowly emerged. We track that emergence here by focusing on the providers of liquidity, the so-called “global financial safety net.”

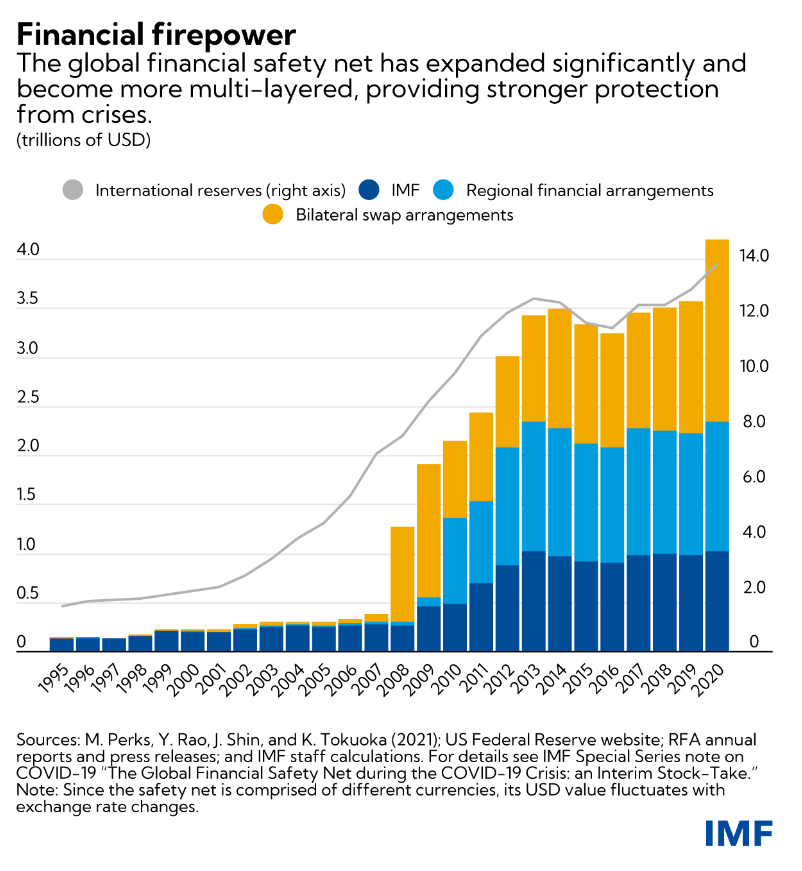

The global financial safety net is a bricolage, not a formal framework. It consists of central bank swap lines, IMF lines of credit, and regional financing arrangements (RFAs) whereby a group of countries pool their reserves. The fourth component is countries’ own international domestic reserves—sovereign holdings denominated in foreign currency.

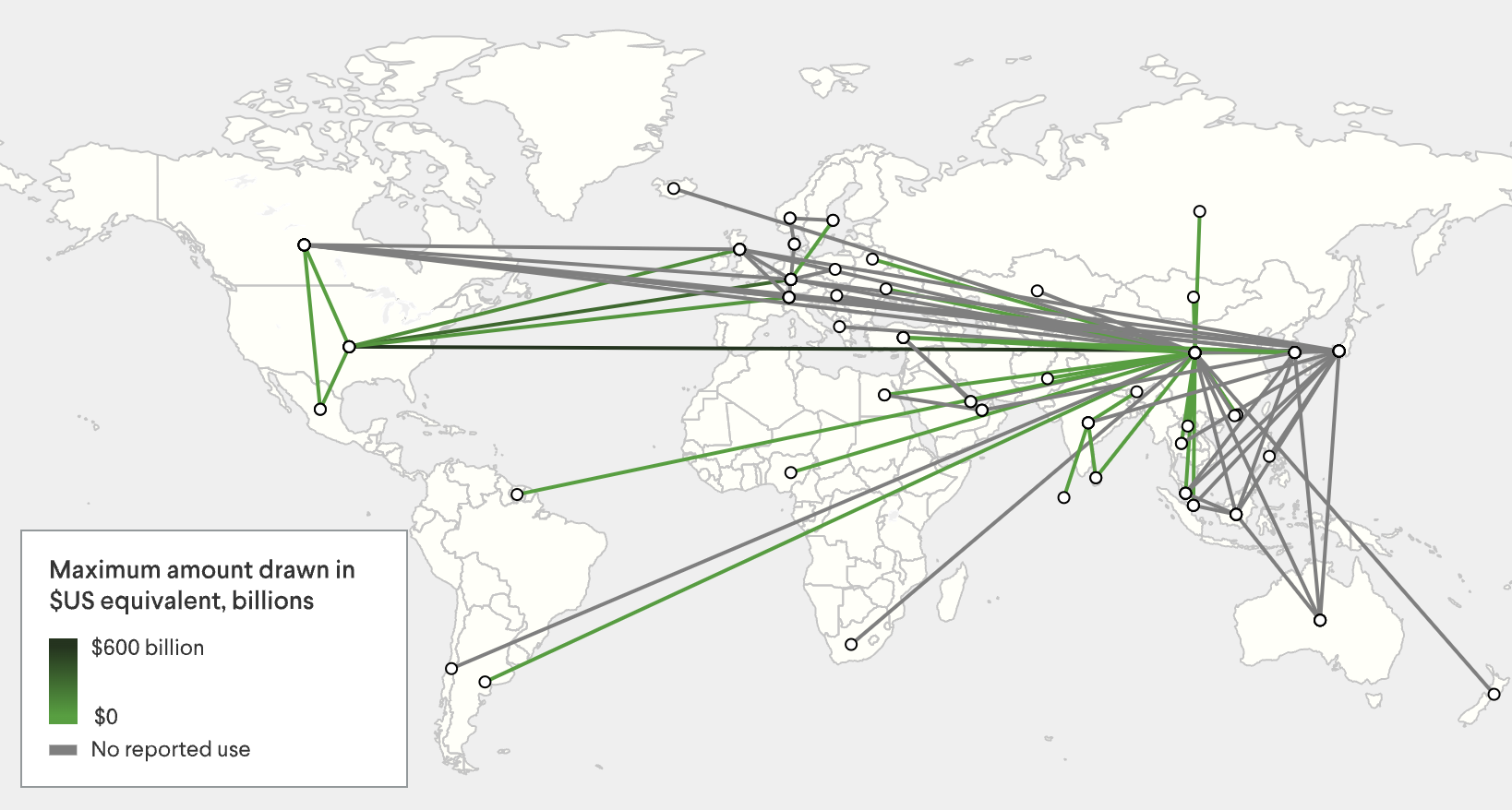

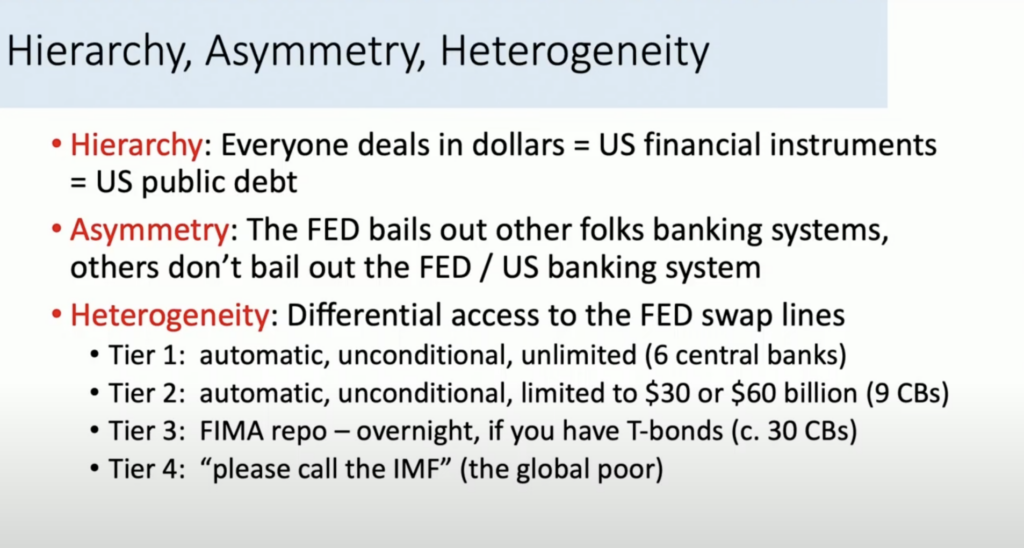

Swaps

In a crisis, the Fed effectively becomes the world’s central bank and is the “lender of last resort” for those countries fortunate enough to be in the inner circle, documents Aditi Sahasrabuddhe. First in line sits the “gang of five,” made up of the European Central Bank, the Bank of England, the Bank of Canada, the Bank of Japan, and the Swiss National Bank. In this top tier, dollar liquidity is provided in exchange for a central bank’s respective currency—it is unconditional, unlimited, fast, and accessible daily. Next in line, nine countries constitute the second tier; Australia, New Zealand, Singapore, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Mexico, South Korea, and Brazil—their access to liquidity is unconditional but limited in quantity. For the rest, terms and conditions apply.

Interest rate decisions made by the five central banks in the top tier create shockwaves for countries lower down. After 2021, rising interest rates attracted foreign and domestic capital toward the top. Lower-tier economies were hit by currency depreciation, surging dollar outflows to import costly commodities (thus fueling their inflation), and soaring borrowing costs. The IMF estimates that capital outflows from emerging markets exceeded $300 billion between late 2021 and July 2022 when the Fed began its current hiking cycle.

Currencies of G20 countries, not just the G77, were sold off and weakened against the dollar in 2021–2023. Even top-tier countries such as Japan are now upset about the strong dollar and are remonstrating at the G20. As John Connally, the US Treasury secretary under Nixon, famously said in 1971: “The dollar is our currency, but it’s your problem.”

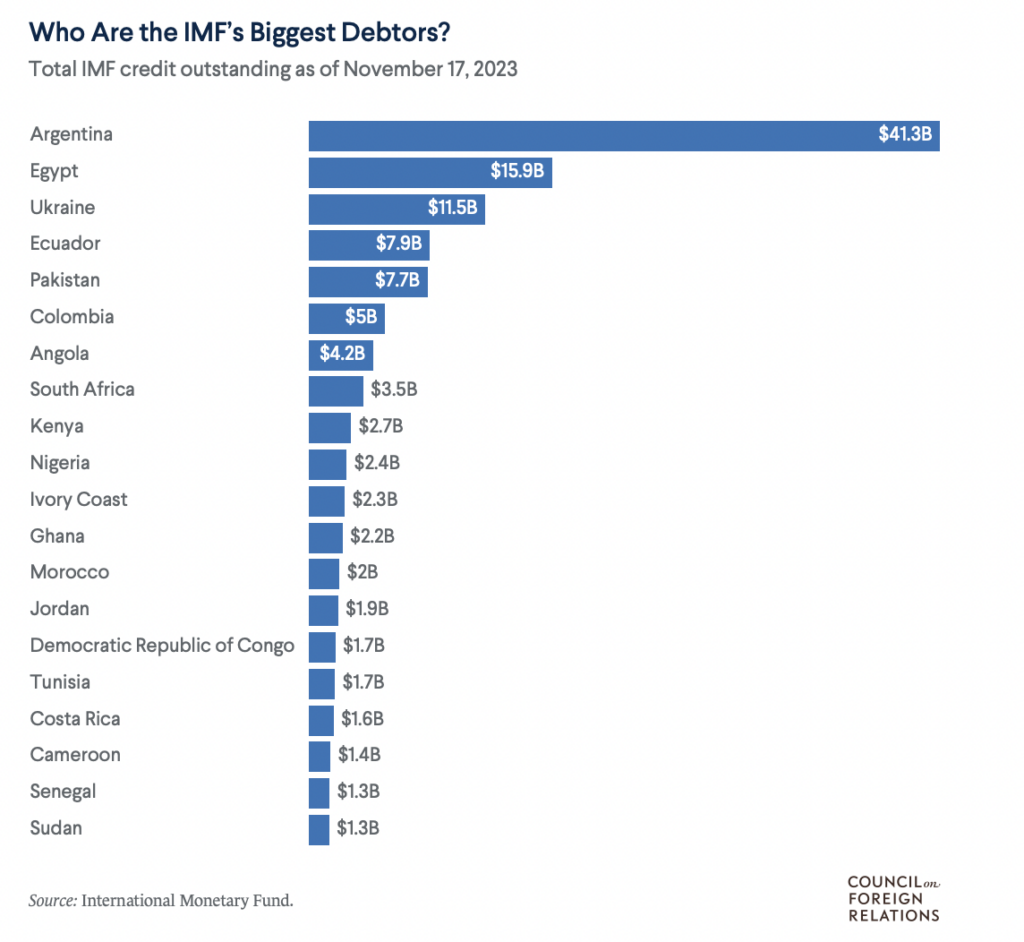

The IMF

As Herman Mark Schwartz’s schema (above) indicates, for all the countries in the periphery of US dollar swaps, the standard pathway for liquidity is the IMF. By some measures the Fund has stepped up since Covid: its lending is at an all time high of $151 billion (denominated in Special Drawing Rights), although that remains a fraction of its total lending power of a trillion dollars.

Its outstanding loans tell a geoeconomic story. The African countries most in need are far down the list. Much of the IMF’s liquidity flows to the countries at the faultlines of the new cold war. Argentina, by far the IMF’s largest borrower, single-handedly holds 30 percent of the IMF’s credit, dwarfing IMF lending to all sub-Saharan countries combined. The second largest borrower, Egypt, got a fresh tranche of $5 billion in March to help Sisi’s regime deal with the blowback from Russia’s and Israel’s wars. Then there is the $15.6 billion lent to Ukraine—the IMF’s seventh largest program in its history. Because of its extremely high rate of borrowing, Ukraine is now facing various surcharges on top of its 3.5 percent interest rate, and the Economist estimates that, all told, its rates could total as much as 8 percent once the war is done—another impending disaster awaiting the country. If this weren’t bad enough, the IMF also wants Ukraine to introduce fiscal reforms—a rather difficult order as Russian bombs continue to fall.

The IMF’s practice of requiring governments to introduce harsh austerity measures in exchange for liquidity have driven many countries to try and shield themselves from needing to engage with the Fund at all.

Self-insuring

The biggest part of the aggregate safety net remains self-insurance—that fourth category of hard currency FX reserves accumulated by individual countries. Some emerging-market countries have built up their own rainy day funds of safe assets issued by the “gang of five” since the 1990s. Korea, India, Indonesia, and other Asian countries that suffered in the region’s financial crisis reorganized their growth models to boost export revenues, aiming to protect their sovereignty against IMF prescriptions. Moreover, they began to borrow in their local currencies and increased domestic food and energy production, hoarding their scarce dollars to avoid a balance of payments crisis.

This self-insurance of international reserves, however, remains very unevenly distributed. Of the $14 trillion in international reserves, IMF chief Kristalina Georgieva said last year that more than $10 trillion was held by advanced and “strong emerging market economies.” She added: “the rest of the world relies on pooled resources of international institutions such as the IMF.”

Alternatives

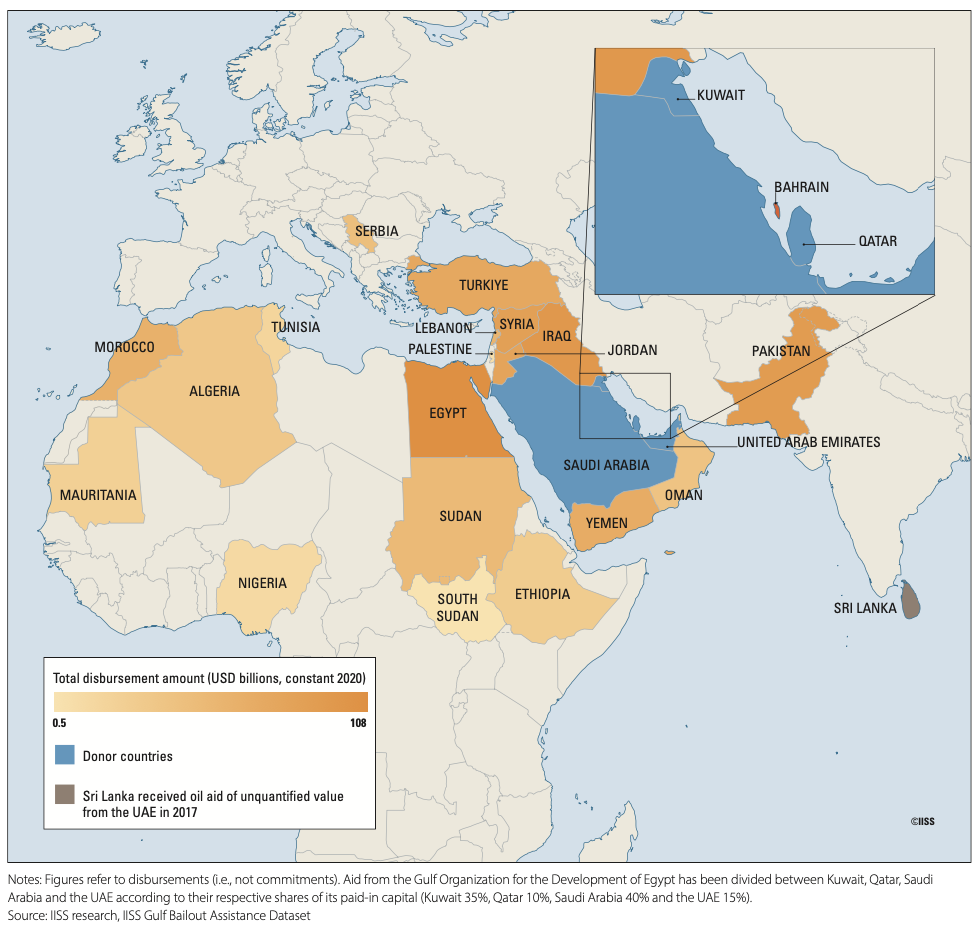

In their own geoeconomic sphere, the Gulf kingdoms have established themselves as lenders of last resort. Camile Lons and Hasan Alhasan at the International Institute for Strategic Studies examined Gulf bailouts to twenty-two African and Asian countries and concluded that they were “unmatched in scale by traditional Western and multilateral donors.” Over the last sixty years, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Qatar, and Kuwait have disbursed an estimated $363 billion to countries, most of which are in the Middle East North Africa region. The largest recipients were Egypt, Iraq, Pakistan, and Jordan, with bailout packages kicking into overdrive after the Arab Spring threatened the Gulf Kingdom’s allies, and again when distress in the region grew after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. In contrast, the IMF has, over the same period, given out $162 billion (in constant 2020 USD) in loans to those same countries.

The IMF’s recent bailout package for Egypt was done in coordination with the UAE, which pumped in a record $35 billion into the cash-strapped country, including prime real estate purchases on the Mediterranean as Sisi sells off his country’s crown jewels.

Much has been made of China’s lending for infrastructure projects over the past fifteen years. Chinese lending for Belt and Road projects is often construed as a novel form of “debt trap diplomacy,” but it more closely resembles familiar and ill-conceived foreign investment fads that other wealthy countries have undertaken before them.

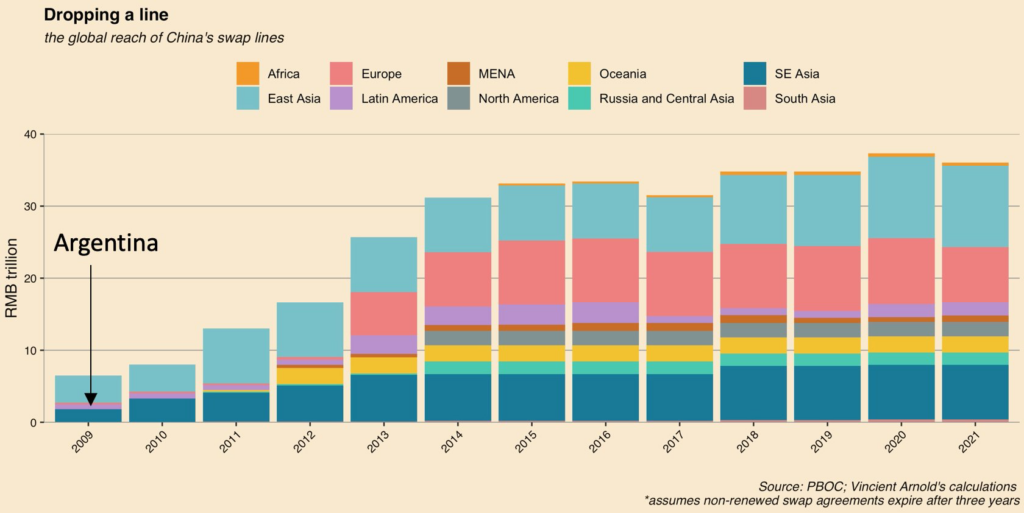

In lockstep with infrastructure and trade, China’s liquidity provision—PBOC currency swap lines and emergency loans by Chinese state banks to countries in the Belt and Road Initiative—has surged in the last decade.

A report by AidData sought to quantify and categorize China’s various “lender of last resort” provisions to other countries (although data availability was an issue). The authors warned that China’s becoming a major liquidity provider could lead to a less transparent global financial architecture. But looking at the present global financial safety net suggests coherence has long been in short supply.

Argentina has been making use of Chinese swap lines for years. It first formalized a swap line with the People’s Bank of China in 2009, and since then the arrangement has evolved and expanded, as detailed by Vincient Arnold. The Argentine Central bank has drawn on the facility to buy dollars, to buy imports and protect its scarce dollars, and most recently, to directly repay IMF debts.

Countries less entangled with the IMF than Argentina also strike swap deals with China. In her paper “It Takes Two to Swap,” Aditi Sahasrabuddhe looked at the political and economic motivations of over 40 countries that signed swap lines with China. She found that for countries that did not have active loans with the IMF, the bilateral swaps with China functioned as a substitute for going to the IMF—a very useful service indeed.

There are even more direct routes to the dollar hierarchy for powerful middle-income countries: India has avoided IMF programs for more than 30 years and hasn’t received Fed swap lines, but as of 2019, it can go to the Bank of Japan for swaps denominated in US dollars.

Regional alliances

Several formal alliances have been created out of dissatisfaction with the IMF, including the Arab Monetary Fund, the Chiang Mai Initiative by ASEAN countries and China, Japan and Korea, the Eurasian Fund for Stabilization and Development, the European Stability Mechanism, the Latin American Reserve Fund, and the BRICS contingent reserves. Some of these RFAs are “aspirational as opposed to operational.” Despite a lending capacity almost as large as the IMF, they have only disbursed about $1.5bn in loans in the first ten months of the Covid crisis and activated $550m worth of currency swaps. The IMF provided $88bn in the same period. Most RFAs were created in the aftermath of regional crises: the ESM after the 2010s European crisis, and ASEAN’s Chiang Mai Initiative after the 1998 Asian financial crisis.

Conspicuously absent from most of these arrangements, whether formal or informal, are Sub-Saharan African countries. Lacking reserves earned through exports, they are largely subject to the IMF’s tender mercies. They are considered not strategically important enough to warrant special measures from larger countries higher up the currency hierarchy. Nor do they trade enough with each other or have enough regional wealth to form an RFA—although new ideas are being proposed (Ghana proposed that countries keep 30 percent of their reserves in African currencies; a facility to improve the liquidity and attractiveness of African eurobonds has launched, but without the G20 support that was originally envisaged). Without powerful friends, financial engineering alone is inadequate.

Polycentrism?

World money has always been geopolitical, as political economist Mona Ali has argued. The global dollar system, headquartered in New York and London, is a “money-military matrix backed by legal armature.”

Most of the non-US arrangements amount to workarounds that are still in service of dollar-based obligations; extending them a little further than US politics would allow for, and with a few less strings than the IMF might demand. The dollar system’s solidity is largely based on the preferences and needs of global elites. Flexing underneath and against that system is likely to continue to be of a limited and ad-hoc nature—more about shielding from disaster and protecting interests than about upending the financialized global dollar system.

Filed Under