On June 22, three leaders of developing countries made expeditions to three different Western capitals to plead their case for greater support from the rich world. Viewed jointly, these demands—largely successful—provide a neat panorama of the escalating global crises of debt, development, and security.

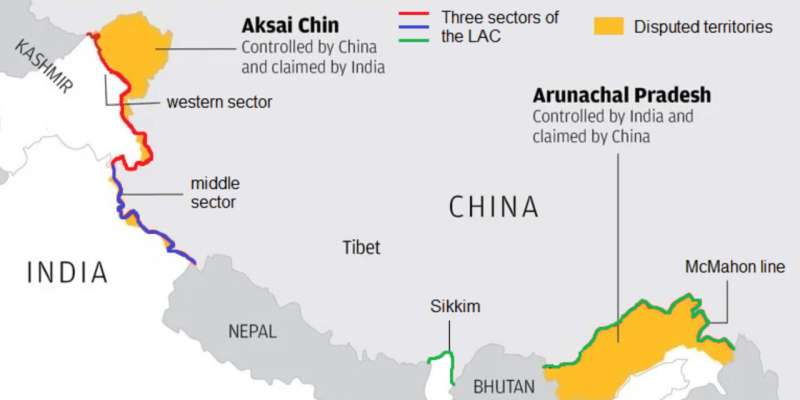

In Washington, India’s Narendra Modi won transfers of sensitive military technology. He insisted that India not only buy GE fighter jet engines, but that his country manufacture them. He bagged the deal, arguing that it would fortify his defensive posture with regard to China.

In Paris, Barbados’s Mia Mottley made the case for reforming the international financial system to afford developing countries the fiscal space to spend on climate and development.

In London, Ukraine’s Volodymyr Zelenskyy pleaded for more capital to finance the reconstruction of Ukraine, and arms to push the Russians out.

This week, as Janet Yellen prepared for the G20 in Gandhinagar, India—her third trip to the country, which she has visited more than any other as Treasury Secretary—she argued that competing demands from the global South are mutually compatible, not zero-sum. Ending the war in Ukraine, she said, was a moral imperative, but “also the single best thing we can do for the global economy.”

The new president of the World Bank had a gloomier assessment. “Beneath the surface, a deep mistrust is quietly pulling the Global North and South apart at a time when we need to be uniting,” Ajay Banga wrote soon after Paris.

Where these crises might once have been conceived of and tackled as separate phenomena, our interdependent risk society is forced to reckon with them simultaneously. Mottley, Zelenskyy, and Modi’s framing of their demands shows how developing countries are determined to shift the global power structure to make their states capable of solving pressing problems. If War Makes the State (pace Tilly), what kind of states are war and climate making?

London

Who will pay for the reconstruction of Ukraine? This was the central question of the Ukraine Recovery Conference in London, attended by ministers and businesspeople from fifty-nine countries last month. According to UK officials, it was “not a pledging conference,” yet pledges were made. These included an additional $1.3 billion from the US, which has already sent the lion’s share—more than all EU countries combined—of aid to the country.

Zelenskyy has been more successful in obtaining materiel, funds, and public support than most developing countries. But a vast “reality gap” exists between Ukraine’s needs & Western delivery. The obstacles at play echo those that recur at international climate summits: A developing country leader insists that the wording on the urgency and scale of the funds required should be strengthened, while rich country leaders seek to limit their commitments. The recipient country’s shortcomings in governance and capacity are cited by donor countries and multilateral development banks; technical solutions are touted.

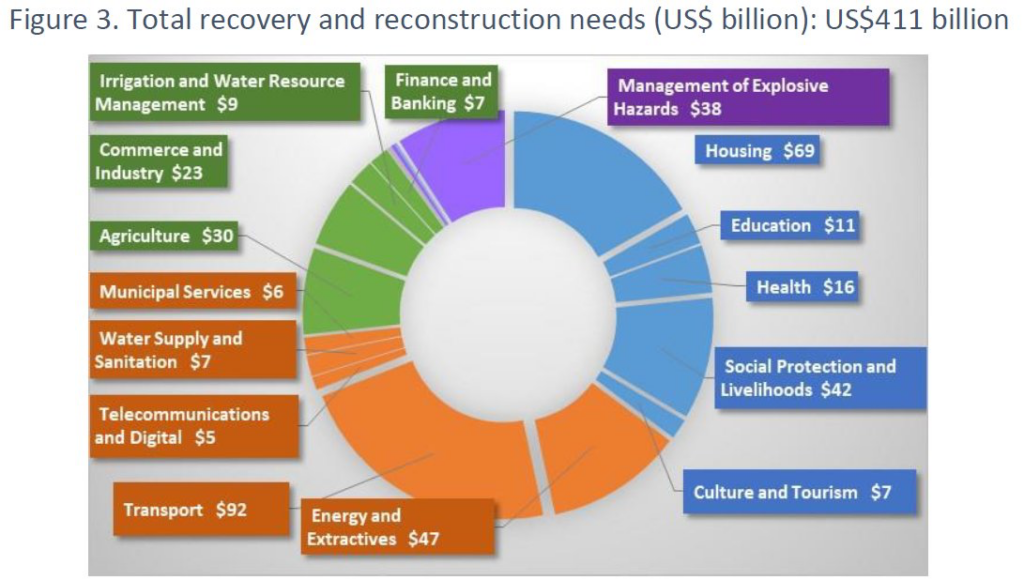

How much damage is there from Russia’s invasion? The World Bank has painstakingly done a Rapid Damage & Needs Assessment, which estimates that total reconstruction costs add up to $411 billion, almost twice Ukraine’s pre-war GDP. That’s the investment required to rebuild housing, power, transport, water, municipal services, etc. Ground teams assessed damages from direct destruction to infrastructure (the Russian army has destroyed almost all power plants and heating) which amounts to an additional $135 billion. The human toll is still more vast. Some 13.5 million Ukrainians—almost 1 in 3 of its pre-war population— have been displaced within the country and across Europe. Seven million people have been pushed into poverty.

As at the Paris Summit, the World Bank reported that money for Ukraine’s reconstruction would come from public-private partnerships, which would, in the classic “billions to trillions” formula, “leverage limited public and donor funding with private investment.”

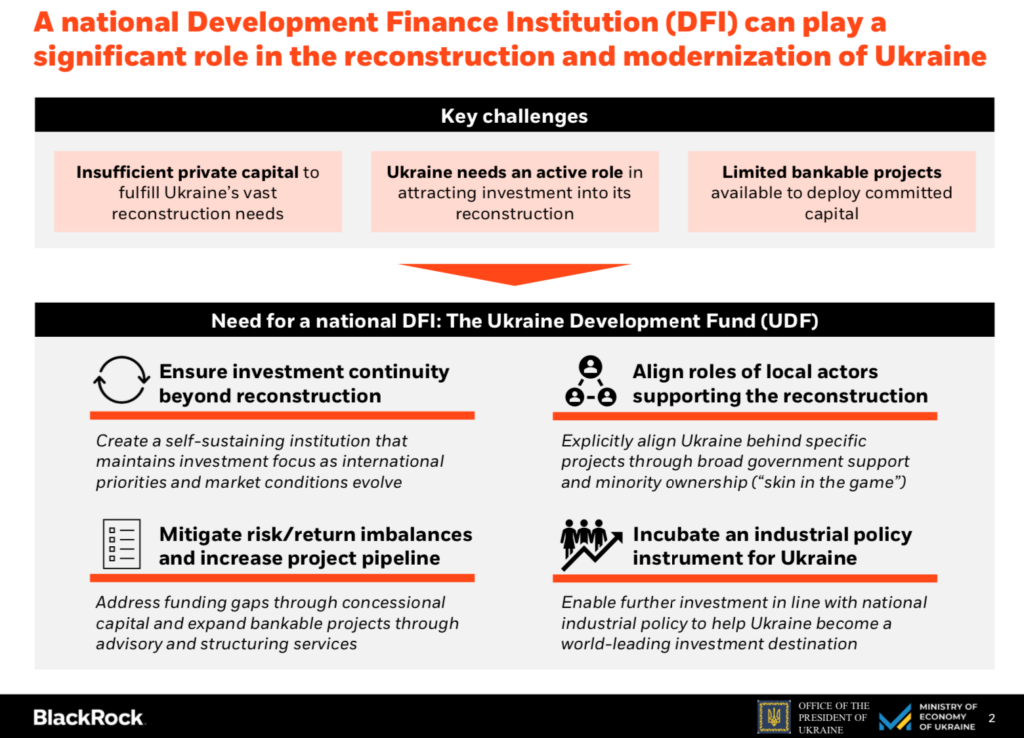

Which companies will invest? BlackRock has signed a Memorandum of Understanding with Ukraine to do the advising and cajoling. Andrew Forrest, the Australian iron ore billionaire and owner of Fortescue Metals, was instrumental in connecting BlackRock with the Ukrainian government. Vying for reconstruction contracts in what the Ukrainian Chamber of Commerce calls the “world’s largest construction site” are nearly 500 businesses from forty-two countries. A New York Times report describes the scene: “Latvian roofing companies and South Korean trade specialists. Fuel cell manufacturers from Denmark and timber producers from Austria. Private equity titans from New York and concrete plant operators from Germany.”

Derisking will be required as few companies want to take large risks without external government guarantees. The risks that companies are wary of are further war, expropriation (i.e. nationalization by Ukraine’s government), transfer and currency conversion risk, and breach of contract. Relaunching a functional insurance market for Ukraine is the priority for the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development and World Bank’s Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency. France and Germany have created funds to compensate investors in case of losses. The EU, too, announced a new multi-year facility of up to €50 billion for recovery, reconstruction, and modernization.

Grants and guarantees only go so far. Ukraine has lobbied the G7 for war reparations. Last week’s G7’s joint declaration says that Russian assets in their jurisdictions—estimated at over $300 billion—will remain immobilized until Russia pays for the damages it has caused Ukraine. The Council of Europe has announced a first step to use frozen assets to compensate victims and support Ukraine’s reconstruction in their “Registry of Damages.” But it is not yet clear if the US will support it. The US has been cautious about setting a precedent in international law that might enable states to demand reparations for US invasions, or be deterred from holding reserve assets in US or EU currency.

What technologies does Ukraine want? Zelenskyy promised to not “replace communist-era rubbish Russian infrastructure” but instead “leapfrog to the latest technology.” Ukraine’s scientists and government have come up with a green recovery plan that emphasizes agriculture, green steel, green hydrogen, and renewables. In short, Ukraine intends to green in a European value chain—that is, in collaboration with other countries.

For the European Union this green reconstruction framework makes it an easy sell to their populations. But Ukraine, as the IMF and EU acknowledge, was riven by oligarchs and underdevelopment before the war. It was one of a handful of countries that became poorer between 1991 and 2018—growing less in those years than all countries but Yemen, Burundi, and the DRC. Remarkably, Ukrainians continue to rank corruption as their top concern in polling, even during the war.

The IMF and EU will function as a disciplinary authority to improve Ukraine’s governance. Ukraine is trying hard to meet EU accession rules. It has promised to strengthen the National Anti-Corruption Bureau and the Specialized Anti-Corruption Prosecutor’s Office.

Paris

While the Ukraine conference was happening in London, Barbados’s leader Mia Mottley was in Paris to make the case for pausing debt repayments and remaking the power structure that forces countries to choose between debt repayments, development, and climate. Her appeal framed problems of finance as problems of war and reparations.

“The UK took a hundred years to repay its debt for World War I and Germany had all the benefits of being able to have its debt service capped at three to five percent of its gross domestic product in order to rebuild after World War II,” she said. “We are people too, we are countries too, and we deserve a similar treatment.”

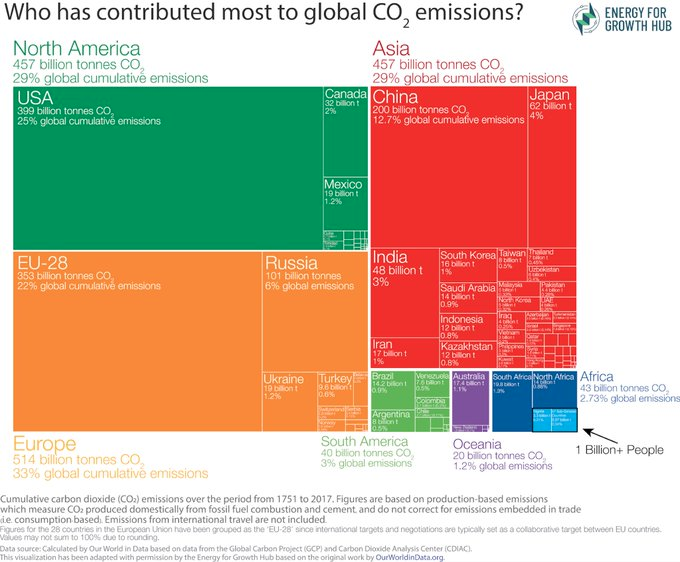

“Those who have really polluted the planet over the last 200 years are those who made the industrial revolution,” Brazil’s President Lula thundered to a large crowd in front of an iconic symbol of that revolution, the Eiffel Tower. “They must pay the historic debt they owe the planet.”

No Western country, however, is prepared to tax the rich or polluters to pay for loss and damage liabilities that are projected to hit $400 billion annually by 2030. In the US, reparations have become verboten. Just last week John Kerry vowed the administration would never support “climate reparations,” under questioning from Republicans in the House.

That more attention was being lavished on Ukraine in London’s conference was repeatedly pointed out by developing country leaders at Paris. (The absence of UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak being particularly criticized by civil society groups.) Kenya’s President William Ruto pointedly remarked that the shareholders of Bretton Woods institutions who are calling the shots were missing from the room. The only G7 country heads of state at Paris were Germany’s Chancellor Scholz and France’s President Macron.

War of territory?

Which war are we in? The late French philosopher Bruno Latour distinguished between two kinds of territorial wars: “the territorial war being waged by the Russians in Ukraine and this other, equally territorial war being waged by the climate crisis in its broadest sense.” For Latour, the physical destruction of large chunks of Pakistan and Nigeria by floods last year was also a kind of lethal violence exercised by richer states that have dumped carbon into our shared atmosphere. He wrote that “we are not dealing with a territorial war in the ‘classical’ sense with additional ‘environmental concerns,’ as we still so strangely say, but rather with two territorial conflicts over the occupation of soils by other States as well as the violence exercised by States on other territories. If it is correct to characterize the conflict in Ukraine as a colonial war, then this is even more so the case with climate wars.”

Washington

In Washington, Biden and Modi signed a series of strategic technology transfer deals. The 58 paragraph Biden-Modi statement, the product of months of negotiations between the US and India, comes off as a “boys and their toys” arcade haul: Fighter Jets! Drones! Artillery! Satellites! Semiconductors! AI! Nuclear reactors! Green Technology!

India is wresting technology transfer from the US to secure itself as a bulwark against China. Slowing growth in India has widened the power gap—military, technological, economic—between the two. India has become more fearful of territorial incursion after China gobbled up a chunk of the Indian Himalayas in 2020. Modi’s pitch to the US congress emphasized technology transfer and co-production. That has been a critical demand of developing countries since the first 1992 UN earth summit in Rio, whose declaration states that besides financial resources, “technologies so developed [should] remain in the public domain and accessible to developing countries at affordable prices.” The chances of Modi’s India pushing an equitable technology transfer agenda multilaterally with other developing countries, instead of looking for its own interests during an intensifying Cold War, remain slim.

No matter the scale of their crisis—a country fighting for its survival, an island nation at existential risk of hurricane destruction, or a subcontinent whose citizens earn a paltry $7 a day —their respective leaders would not portray themselves as hapless victims, but as agents of their own destiny.

Filed Under