This essay first appeared in GREEN, a journal from Groupe d’études géopolitiques.

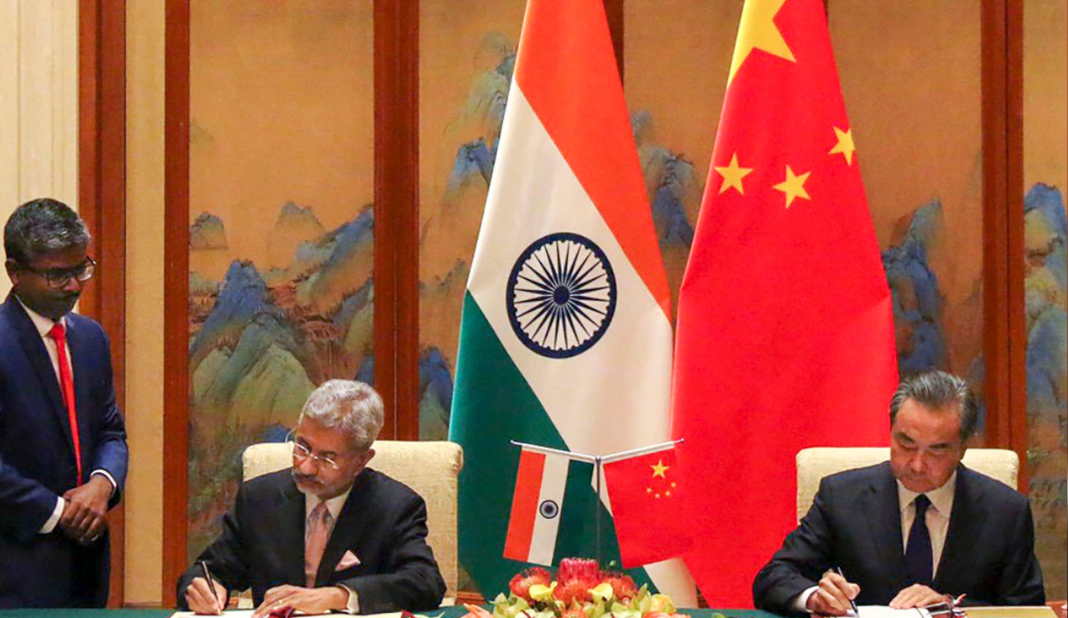

In March of this year, as Russia’s war in Ukraine intensified, China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi made a trip to New Delhi to speak with his Indian counterpart S. Jaishankar. “If China and India spoke with one voice, the whole world would listen,” Wang argued. “If China and India joined hands, the whole world would pay attention.” The geopolitical scales soon started to tilt India’s way.

By April, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen had made her first trip to Delhi, where she laid the groundwork for several weeks of frenetic EU-India dealmaking for a sweeping agenda ranging from defense to green manufacturing.

The following month, in a whirlwind three-day tour of Germany, Denmark and France, Prime Minister Narendra Modi won concessions that Indian policymakers have coveted for well over two decades, ranging green-energy investments, tech transfers, and weapons deals, putting flesh on the bones of a moribund EU-India strategic partnership.

In Berlin, Chancellor Olaf Scholz announced a €10 billion green partnership to help India achieve its 2030 climate targets and high-tech transfers. The next day in Copenhagen, Nordic countries signed wind and solar deals, alongside green shipping and green cities investments. In Paris, Macron signed deals to invest in India’s green hydrogen hubs as well as increase sales of French military aircraft and ships; for its part, Électricité de France confirmed a long-pending deal to build six EPR-1650 nuclear power reactors in Jaitapur. This followed India’s momentous $42 billion investment deal with Japan for electric vehicles (EVs), green hydrogen/ammonia, and heavy industry transition.

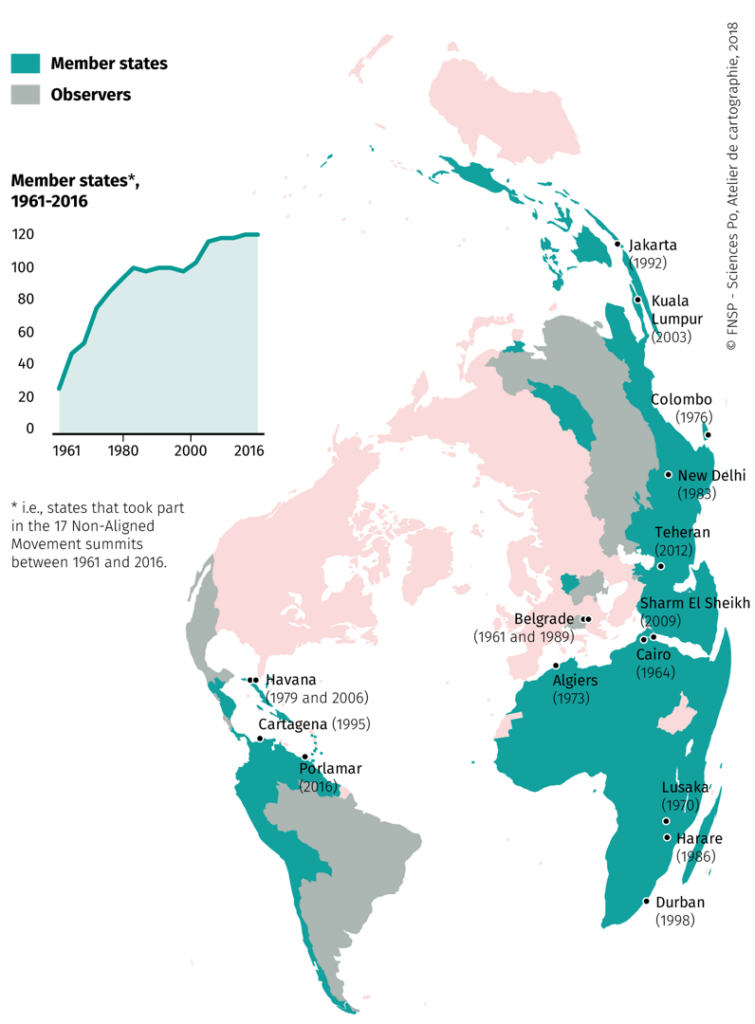

The timing of these rapid concessions is no accident. The divorce of China, Russia, and the West is providing Modi with a golden opportunity to negotiate a new geopolitical order. As the world splits into new Cold War blocs—which look strikingly similar to the old Cold War blocs—the old Indian grand strategy of non-alignment is reemerging. And this time, the rise of China assures that the new counter-hegemonic bloc will enjoy considerably greater resources than the former communist powers ever did.

That emboldened confederation stretches beyond the subcontinent. India’s last thirty years of catchup growth were achieved in an era of US global primacy. Along with other developing nations who have interests independent of the US, today, a much richer India has the leverage to challenge the coercive underbelly of American hegemony. Brazil and Indonesia, too, are taking advantage of their new pull. Neither the United States nor Europe should underestimate postcolonial elites in their renewed efforts to chart an independent course.

Friction with the West is assured. But diplomats in the developing world are prepared to pay to avoid a costly and risky confrontation with the Sino-Russian axis. Developing countries’ answer to the West’s question, “Do you want to contain China with us?” is probably “Yes.” But the answer to the question, “Do you want to contain China and Russia with us?” is probably “No.”

Since 9/11, the US Department of the Treasury, National Security Agency, and Department of Commerce have developed a Panopticon over the key networks of globalization. The Treasury’s Office of Foreign Asset Control and the SWIFT payments system surveilled financial channels; Edward Snowden’s Silicon Valley surveillance internet provided a view into the flow of information; and the export control list of technologies gave it a map of supply chains. Key choke points were located and operated in the advanced industrialized states of the G7. Meanwhile, the US became more willing to weaponize the dollar system against troublemakers. The signal to developing countries was clear: if threatened, the US will exert its control over the technologies underpinning economic growth and military superiority.

The G7’s command of key technology remains the source of its hard power, as demonstrated by the design of its economic-warfare sanctions against Russia following its latest invasion of Ukraine. Sanctioning Russia’s central bank assets and cutting off access to the SWIFT system signaled financial war. Then, a technological iron curtain fell, blocking high-tech exports to Russia’s economy as well as critical airplane parts, while the G7 sought to block the supply of silicon chips (a key component of military hardware) from Korea and Taiwan. In October, the US escalated its containment of China by export control restrictions on chips.

Countries like China, India, Indonesia, Brazil, South Africa, Mexico, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates have refused to sacrifice their national interests to punish Russia. Most importantly, they believe their bargaining power in the new Cold War will result in sweeter trade, technology, and weapons deals from the West. These eight countries alone will account for three-fourths of the world’s population and 60 percent of its economy by 2030. They have aspirations for regional dominance and believe non-alignment better serves their interests.

Little wonder, then, that these countries are adopting a stance of non-alignment to secure the same key technologies—fighter jets, green technology, chips, submarines, nuclear, advanced pharmaceuticals, 5G mobile networks—that could power their catch-up growth. The map of countries that remained neutral on Russia sanctions is no bleeding-heart protest for global justice, but a hard-nosed security play. Before signing up to the West’s new financial-technological-military regime, these countries intend to extract maximum concessions. They are also betting that the West will tolerate their foot-dragging on Russian sanctions, and refrain from imposing secondary sanctions (sanctions for breaking sanctions) on them. Threats to exit, as any bargainer knows, confer power.

What exactly do the countries flirting with a new non-alignment want?

1. Core technologies to power future growth;

2. Advanced military hardware for enhanced security;

3. The upper hand in trade negotiations with Europe, the US, and the new Russia-China bloc;

4. Essential commodities like food, energy, metals and fertilizers from the new Russian-Chinese bloc;

5. Better terms to restructure their debt to Western and Chinese creditors during a punishing global dollar debt crisis that threatens their sovereignty.

Reliance, the Indian conglomerate owned by billionaire and Modi-backer Mukesh Ambani, encapsulates developing countries’ relationship with the G7. Ambani’s Jamnagar refinery makes billions importing Russian crude oil and exporting diesel and gasoline to the West. Despite its flouting of Western sanctions, it continues to receive green technology transfers from the West. It has invested more than $60 billion of its own cash and $10 billion in partnerships and acquisitions of electrolyzers to manufacture hydrogen (from a Danish firm), photovoltaic wafers (from a German firm), solar panels (from a Norwegian firm), grid-scale batteries (from a US firm), and iron-phosphate batteries (from a Dutch firm).

India’s management of these foreign partnerships will depend on Dubai. UAE President Mohammad bin Zayed has positioned the Gulf Kingdom as a Club Med for oligarchs and merchant banks to skirt Western sanctions. Gulf petrostates are set to gain an additional $1.3 trillion in petro (dollar) exports over the next four years. Dubai lets non-aligned countries bypass sanctions, using commodities payments settled in yuan, rupees, and rubles to bypass dollars. Biden’s Persian Gulf policy is adapting, with talk of security guarantees for the UAE and a new partnership with the US for a $100 billion clean energy financing deal for developing countries. Gulf sovereign wealth funds are meanwhile investing in the energy transition across Eurasia. It’s the old Indian-Arab-European sugar, spice, cotton trade route back with a bang.

Under President Joko Widodo, Indonesia, too, is making its move by taking control of its abundant supply of nickel and copper—essential for the energy transition—and incentivizing investment in processing facilities. If the dream of becoming an electrostate is new, the tools are old. Indonesia is copying the developmentalist state successes of the East Asian Tigers as well as the 1970s nationalization drives of the OPEC countries. To howls of outrage by the European Commission at the World Trade Organization, Jokowi banned exports of nickel, forced international companies to refine and process it domestically, and sought technology transfer to state-owned enterprises.

Indonesia has the largest nickel reserves in the world, with a majority controlled by its state-owned mining company, MIND ID. After Jokowi banned nickel exports, Chinese companies agreed to set up joint ventures in Indonesia along with transfer of critical high pressure acid leach (HPAL) technology that is required to make battery-grade nickel. While Germany’s Volkswagen, Brazil’s Vale, and the U.S.’s Ford and Tesla initially sought to secure unprocessed nickel from the country, Indonesia insisted on grabbing more of the value chain by creating an EV-producing national champion, Indonesia Battery Corporation, which has struck partnerships with China’s CATL and South Korea’s LG to obtain critical HPAL technology for battery-grade nickel.

Jokowi’s next targets for the “ban-exports-and-nationalize” treatment are tin (Indonesia is the world’s second largest producer and the metal is used as solder to make electrical connections), aluminium (Indonesia is world’s fifth largest producer and the metal is used in electricity and cars) and copper (used in, well, everything electric).

Such policy independence nonetheless remains limited in the face of American sanctions. After the US threatened any client for Russian weapons with economic warfare, Indonesia canceled its planned purchase of Russia’s Sukhoi-35 fighter jets, despite Russian offers of a dollar bypass palm-oil-for-fighter-jets scheme. Instead, Indonesia undertook a major escalation in defense spending to buy thirty-six US F-15s and forty-two Rafales from France, along with two of France’s Scorpene submarines (the latter an emollient after France lost out on its sale of diesel subs to Australia) at a total cost of $22 billion. When Russia shipped two S-400 air defense missile systems to India in 2021, it prompted a furious backlash from the US and threats to sanction India for the deal. Calls for constructive, non-coercive sanctions, remain unheeded.

Perhaps most surprisingly, given his regime’s proximity with the US, outgoing Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro chose neutrality in the war. The material stakes make this choice seem obvious—Brazil’s soy, corn, sugar, and meat exports are heavily dependent on Russian fertilizers, and so Bolsonaro has had an enormous stake in preserving relations. Moreover, Brazil’s trade surplus with China is bigger than all its exports to the US But the ideological current runs deeper.

Under Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, Brazil deepened relations not only with the BRICS and other Pink Tide governments, but also with the US. In 2011, the foreign minister boasted that Brazil had more embassies in Africa than Britain did. That willingness to make friends in both the Pacific and North Atlantic has given it greater room to maneuver, as when it broke HIV/AIDS drug patents in favor of Indian generics.

Bolsonaro’s free-market faction broke with that multilateralist tendency, siding against India, South Africa, and China when that bloc demanded Covid-19 vaccines free of intellectual property (IP) limitations at the World Trade Organization. It also joined the G7 on agricultural free trade policy, and sat out IP fights. Yet the Brazilian right’s best efforts to quash protectionism were not enough to overcome the country’s long aversion to G7 coordinated schemes; Brazil still chose neutrality on Russian sanctions. Elites in Brasília would rather keep their options open and their commitments light.

Green industrial growth compels some hard choices. Looking ahead, Brazil will need to prioritize either domestic industrialists or external allies as it weighs whether to develop flex-fuel cars fed by homegrown sugarcane ethanol or batteries sourced from China, Indonesia, and the nearby lithium triangle. In his victory speech, flanked by trade unionists and landless peasants, Lula pledged to pursue strategic non-alignment: “We will not accept a new Cold War between the United States and China. We will have relations with everyone.” Brazil may defer choosing between North and South, but the choice between an inward-looking Brazil or an outward-facing one looks inevitable.

There was a special irony to Brazil’s right-wing capture. Under Bolsonaro, the country was perhaps the most cooperative with the G7-led order of any BRICS country. But Lula represents the developing world’s best shot at leading a global non-alignment movement. Whereas the old non-aligned movement was anchored by moral imperatives—decolonization, anti-racism, nuclear disarmament—this fledgling version lacks a positive social and ethical program. Instead, it stems from the cold commercial and security logic of development. It will be up to that former unionist metalworker to forge a new coalition based on shared values.

Developing countries will use this decade’s violently shifting geoeconomic conditions to build on old growth models, including industrial policy and developmental-state capitalism. Expect states like India and Indonesia to keep imposing conditions on their increasingly coveted cooperation and access to growing consumer markets on hard infrastructure deals.

If this is the general trend, there will be enormous variations in strategy. Brazil’s program of development through social policy, including the signature Bolsa Familia cash grants, may be fully realized with Lula’s return to power. Indonesia and India—who hold outgoing and incoming presidency of the G20—meanwhile, have favored policies centered on the buildout of electricity, roads, and ports, which can disregard human rights and bias deals toward powerful incumbents. In the extreme version, consider the Gujarat model that has formed the basis of Modi’s aggressive electoral campaigns.

The new non-aligned countries play the G7 powers off each other. Most exposed to this shifting terrain of economic and security relationships are Germany, Korea, and Japan whose industrial firms fear loss of their export markets. Thus far Germany is distancing itself from the decouplers in Washington. In his recent visit to China, Chancellor Scholz, flanked by CEOs of BASF and Volkswagen, said “New centers of power are emerging in a multipolar world, and we aim to establish and expand partnerships with all of them.”

Even as non-aligned countries negotiate within the new sanctions regime and find ways to use it to their advantage, we should not lose sight of the devastating toll of G7 sanctions, a blunt instrument that has torn up supply chains and created inflationary pressures. When emerging market elites can parley these conditions to their advantage, it is impressive. But even the most creative trade deals struck under terms set by the G7 are insufficient buffers against food and energy price volatility, unleashed by deregulated commodity markets run out of London and Chicago. Climate chaos on every continent, meanwhile, compounds these tensions, devastating the already threadbare lives of many. All the more reason, then, for the G7 to take a leaf out of the BRICS’ playbook and coordinate investment in long-term sustainable infrastructure.

Filed Under