The election of Prabowo Subianto to the Indonesian presidency two months ago has been warmly welcomed by the country’s business and political elites. The day following the result, the Jakarta composite index rose by 1.3 percent, a tacit sign of assent for President Joko Widodo’s chosen successor, who was always expected to win the vote. Prabowo (as he is popularly known) has promised continuity with Jokowi’s (as he is popularly known) ten-year regime, emphasizing infrastructural development and downstream industrialization. Prabowo also shares Jokowi’s ambition to overcome the so-called middle-income trap before Indonesia’s hundredth anniversary of nationhood in 2045. This is a serious undertaking, which would entail a growth rate of at least 6 or 7 percent. This target was achieved for three decades after the fall of Sukarno in 1967 but could not be maintained in the aftermath of the Asian Financial Crisis; between 1999 and 2014, growth sat at around 5 percent. Despite his effort to attract foreign investment and build up Indonesian industry, Jokowi’s development model proved unable to lift rates any higher.

As Prabowo assumes the helm, the pressure to generate growth is only intensifying. With a highly nationalist ideology and a powerful circle of business elites championing his administration, there are concerns that Prabowo will be progressively drawn toward illiberalism. An anti-democratic shift was already visible under Jokowi, and Prabowo’s populist vision of state-led development is likely to exacerbate it. The result may be disastrous, not only for the country’s institutional infrastructure but for vulnerable and marginalized groups at the bottom of the economic pyramid, as state-backed development projects are likely to threaten their livelihoods.

Jokowi’s legacy

Jokowi’s 2014 election, as outlets like the Economist declared, marked a period of “new hope” for the future of Indonesian democracy. For the first time, the country would be led by a layman who had no direct connection with its entrenched political and military aristocracies. As such, it could just as well be said that celebrations were prompted by the defeat of Prabowo—the former son-in-law of Indonesia’s former dictator General Soeharto—who, in 2014, was considered too close to the establishment. “Jokowi’s election victory,” wrote one reporter for Time, “symbolized the electorate’s triumph over a ruling clique that had long treated this resource-rich nation as a private fiefdom.”1

Hope for the president-elect also bore an economic dimension. Jokowi set the ambitious goal of raising Indonesia’s annual growth rate above 7 percent, which he hoped to achieve through infrastructure investment and downstream processing. In his 2016 State of the Nation Address, he promised to accelerate the development of key infrastructures, which would be funded with cuts to fuel subsidies. These included the addition of 35,000 megawatts of electricity to the grid, upgrading or building five port hubs and nineteen feeder ports, developing 3,650 kilometers of new roads, and achieving 100 percent access to clean water nationwide. The government also promised to build or rehabilitate dams to raise food production.

Jokowi did make some impressive gains: within four years, infrastructure expenditures more than doubled, from USD 13.03 billion in 2014 to USD 26.85 billion in 2018. From 2018 to 2023, the country spent an average of $27 billion per year on infrastructure.2 Around 1,885 km of toll roads were built between 2014 and 2022 and a target was set for building a further 1,800 km of toll roads.3 Jokowi’s administration also built 31,410 km of new (non-toll) roads, as well as 1502 new ports and fifty new airports across the country in the same period. The country’s electricity capacity increased by twenty gigawatts and the electrification ratio rose from 81.5 percent in 2014 to 99.63 percent at the end of 2022.4 Between 2015 and 2022, the government completed the development of thirty-six dams capable of watering 245,103 hectares of crop fields. It aimed to build twenty-five more dams in the following two years.5

Impressive as this was, the administration also demonstrated crucial shortcomings. Upon election, Jokowi faced immense political resistance that meant a degree of marginalization. In order to regain a position of authority, he retracted his promise to build a narrow-based coalition dominated by non-partisan professionals, instead developing a broad-based coalition government including parties affiliated with Prabowo. The reshuffle increased the proportion of seats Jokowi controlled in the legislature; after having as few as 37 percent of legislative seats in his control, by the end of his second term, he controlled 71 percent.6 Another area of concern under Jokowi has been democratic backsliding in key areas—from horizontal accountability to civil-military relations and civil liberties. The Economist Intelligence Unit estimates that Indonesia’s democracy index declined from its historic peak of 7.03 in 2015 (just a year into Jokowi’s first term) to its historic low of 6.3 in 2020. The score increased to 6.71 in the following year before declining again to 6.53 in 2023.7 According to the Freedom House, political rights and civil liberties continued to decline during this period and Indonesia today is categorized as “partly free.”8

A key problem is executive aggrandizement.9 Not only did the government suppress party-based opposition, it also repressed its critics and opponents from civil society organizations. It by no means held back from replacing opposition leaders with pro-Jokowi politicians in party leadership circles. This is evident, for example, in the replacement of Suryadarma Ali with Muhammad Romaharmuziy in the Partai Persatuan Pembangunan (United Development Party, PPP) and Aburizal Bakri with Setya Novanto in the Golkar Party in 2016. The intervention had the predictable effect of weakening internal contestation within the party and its capacity for political representation.10 Outside the party system, the government’s repressive measures against critics and opponents within civil-society organizations eroded civil liberties. In 2009, only 17 percent of respondents believed that people were afraid of talking about politics. Five years after Jokowi took office, the figure soared to 43 percent. Fear of arbitrary arrest also rose from 27 percent in 2009 to 38 percent in 2019.

The consolidation of power would continue in Jokowi’s second term. Defeating Prabowo for the second time in 2019, Jokowi surprised voters by appointing the latter as his defense minister. The appointment enabled the military to expand its political influence, regaining internal security functions formerly transferred to the police and taking a larger proportion of seats within the state bureaucracy.

A degree of democratic backsliding, it was argued, was necessary to achieve economic growth. Jokowi’s development projects were predicated on undermining the Corruption Eradication Commission (Komisi Pemberantasan Korupsi, KPK), the only credible law enforcement agency in the country. During his first days in office, he cultivated an appearance of rectitude by integrating the KPK in the selection of ministers and other high-ranked officials. But he backed down when KPK’s aggressive acts against corruption affected his development projects and generated strong resistance from business and political elites. He revised KPK’s legislative independence, which resulted in proliferating corruption. Indonesia’s Corruption Perception Index (CPI) score rose and then fell during Jakowi’s incumbency. It increased from thirty-six in 2015 to thirty-eight in 2021, and the country ranked ninety-sixth out of 180 countries surveyed. Yet Indonesia’s CPI score dropped to thirty-four in 2022, and the country ranked 110th out of 180 countries.

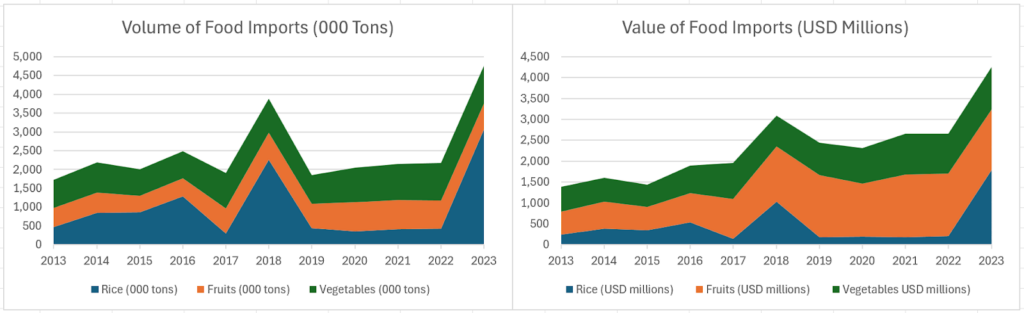

Jokowi’s economic record is mixed. Even with the increased number of dams, Indonesia is struggling to meet its domestic food demands. Food imports increased significantly under Jokowi’s presidency. In 2014, Indonesia imported nearly 2.2 million tons of rice, fruit, and vegetables at a value of approximately USD 1.6 billion. By 2023, however, food imports had risen to 4.7 million tons with a soaring value of USD 4.3 billion.

Figure 1: Indonesia’s Food Imports, 2014–2023

Logistics is another area of concern. Despite the massive development of roads, ports, and airports, Indonesia’s rating dropped in the World Bank’s Logistics Performance Index (LPI), which includes customs, infrastructure, international shipments, logistics quality and competence, and tracking and tracing. Despite improving from sixty-third in 2016 to forty-sixth in 2018, it sank back down to sixty-third in 2023. This was a rating lower than its neighboring countries, especially Thailand (thirty-fourth), Malaysia (twenty-sixth), and Singapore (first). There is reason to believe that this low performance is linked to higher levels of corruption—countries with higher LPI scores usually score better on the Corruption Perception Index (CPI).

Outcomes in downstream processing have been mixed as well. Since 2009, Indonesian mining laws have prohibited the export of unprocessed minerals and mandated companies to process or smelt their ores domestically. The laws gave mining companies five years to develop processing facilities before the export ban would be implemented in 2014. However, delays in the development of smelting facilities by mining companies and changes in the government’s calculations in the mineral sector compromised the implementation of the policy. It was not until Jokowi’s second term that the export ban was implemented seriously. Beginning in 2020, the Minister of Energy and Minerals banned nickel ore exports with the aim of extending the ban to other minerals in the following years.

Foreign investments in downstream processing under Jokowi have increased significantly (rising from USD 4.36 billion in 2019 to USD 24.63 billion in 2023)11 and, as a result, so have metal exports. Indonesia’s iron and steel exports rose from 4.5 million tons in 2018 to 14.9 million tons in 2022, while ferronickel exports increased from 0.9 million tons to 5.8 million tons during the same period. Job creation as a result of these increases, however, has been weak. The refining and processing of mineral ores is capital- and technology-intensive but this by no means translates into labor absorption. The share of labor in manufacturing, for example, fell from 14.17 percent in 2022 to 13.83 percent in 2023.

Potential trajectories

The election of Prabowo, who is known for his close ties to the oligarchy, signals the growing influence of political and business elites in Indonesia. Prabowo’s military career took off under the reign of his father-in-law, General Soeharto, and he has admitted to his role in abducting student activists—some of them still missing—in 1998. Following some years of political exile in Jordan, in the early 2000s Prabowo returned to Indonesia to build his political career and run his companies, which operate in sectors ranging from coal mining to forestry and plantation. With a total net worth of USD 130.77 million or IDR 2.04 trillion, Prabowo was the wealthiest presidential candidate in 2024.12 His brother and main supporter, Hashim Djojohadikusumo, chair of the Arsari Group, was, according to Forbes, the fortieth richest person in Indonesia in 2022, with total assets worth USD 685 million or IDR 10.4 trillion.13

Hashim is certainly not the only conglomerate behind Prabowo. A few days before the presidential election, Garibaldi Thohir, CEO and a significant shareholder of Adaro Energy—one of the world’s largest coal exporters—declared his support. A number of national conglomerates also pledged their support to Prabowo’s national campaign, including Aburizal Bakrie, Hatta Rajasa, Pandu Patira Sjahrir, Putri K. Wardhani, Erwin Aksa, Theo Sambuaga, Totok Lusida, and Wishnu Wardhana. Rosan Roeslani, the chair of Prabowo’s National Campaign Team, is the former chair of the Indonesian Chamber of Commerce and Industry (KADIN Indonesia) (2015–2021). According to Jaringan Advokasi Tambang, coal tycoons backed Prabowo as well.14

This consolidation of political and business power will allow Prabowo to pursue long-term economic development, and continue Jokowi’s infrastructural and downstream industrialization projects. But there is no guarantee that such development will translate into higher rates of growth. Since mineral processing is capital-intensive, most of the benefits from it will be reaped by Chinese companies, which are the main investors.15 Some analysts, including former vice president Jusuf Kalla, have lamented the dismal gains from nickel exports being directed into government’s coffers. Rather than imposing export bans, many have argued that what Indonesia needs most is improved logistics systems. This would allow companies to maximize benefits from mineral exports and strengthen the structure of the domestic industry.16 More resources will also be needed to expand research and development capacity across the board, but especially in agriculture, given farmers’ limited resources.17

The government’s food estate program has been criticized not only for violating community-based notions of food sovereignty, but for not delivering on its promise of enhancing food production. The military’s involvement in the program has also attracted criticism. In its current construction, the program serves the interest of the political and business elite more than the farmers.18 Similarly, reports about the negative impacts of nickel mining on the livelihood of local people abound. Not only did the mining exacerbate deforestation trends, it also adversely affected the rivers and coastal areas where mining companies dumped waste. Some evidence also indicates that poverty in the regions where nickel was extracted and processed has increased in the last few years, suggesting the negative impacts of mining on the livelihood of local communities.

So far, Prabowo has not indicated how his economic programs would respond to such criticisms. Yet, a few days after his electoral victory was announced, his team stated that the government’s economic programs will focus on three main drivers, namely food, energy, and manufacturing. In line with the leader’s nationalist narrative, the team framed these programs in terms of building economic self-reliance. Prabowo has made the case for economic nationalism before, writing that “we expect the government should not be hesitant to get involved and drive economic growth.” He has broadly received assent on this topic among the bureaucracy, political parties and the private sector, with only a few economists and liberal intellectuals openly criticizing Prabowo’s nationalism.

In 2024, it seems doubtful whether such a statist model of development will achieve a meaningful distribution of wealth. Income inequality remains fairly high in Indonesia, with a stubborn Gini ratio of 0.39. Addressing inequality will require more than industrial development. It will need a strong, broad-based green coalition to push sustainable and equitable development agendas. The country does not lack vibrant social movements pushing such agendas: JATAM, Greenpeace Indonesia and WALHI (Wahana Lingkungan Hidup Indonesia, or the Indonesian Environmental Forum) all address economic justice, while AMAN (Aliansi Masyarakat Adat Nusantara, or the Alliance of Indigenous Peoples of the Archipelago), SPI (Serikat Petani Indonesia, or the Indonesian Farmers Union), and KPA (Konsorsium Pembaruan Agraria, or the Consortium for Agrarian Reforms) are focused on economic rights. Indonesia also has numerous trade unions and, more recently, a new Labour Party. Non-governmental organizations such as Ganbate (Gerakan Energi Terbarukan, or the Renewable Energy Movement) have also emerged, and are working on energy transition issues. Despite positive developments, these issues often remain siloed, with organizations operating in isolation from each other. A broad-based green coalition, consisting of these organizations and other actors, including those from the private sector, is needed to address the country’s new political and economic challenges. Credible pressures from such a coalition can be a powerful instrument to defend the economic interests of the lower economic classes and advance the green economy.

Hannah Beech, “The new face of Indonesian democracy.” Time, 15 October 2014. https://time.com/3511035/joko-widodo-indonesian-democracy/

↩Aulia Mutiara Hatia Putri, “Infrastruktur era jokowi masif, total anggarannya wah!” CNBC Indonesia, 23 February 2023. https://www.cnbcindonesia.com/research/20230223080242-128-416219/infrastruktur-era-jokowi-masif-total-anggarannya-wah.

↩Widya Finola Ifani Putri, “Simak! Sri mulyani beberkan data pembangunan jalan era jokowi,”CNBC Indonesia, 19 May 2023. https://www.cnbcindonesia.com/news/20230519165750-4-438863/simak-sri-mulyani-beberkan-data-pembangunan-jalan-era-jokowi

↩Uliyasi Simanjuntak, Kurniawati Hasjanah, “Electrification ratio doesn’t address the reliability of electricity quality in Indonesia,” Institute for Essential Service Reform, August 22, 2023. https://iesr.or.id/en/electrification-ratio-doesnt-address-the-reliability-of-electricity-quality-in-indonesia.

↩Tri Murti, “Future govt must focus on building dams,” PwC Indonesia, 15 June 2023. https://www.pwc.com/id/en/media-centre/infrastructure-news/june-2023/future-govt-must-focus-more-on-building-dams.html

↩Andrea Lidwina, “DPR Dikuasai Partai Koalisi Jokowi,” Katadata Media Network, 25 October 2019. https://databoks.katadata.co.id/datapublish/2019/10/25/dpr-dikuasai-partai-koalisi-jokowi.

↩Economist Intelligence Unit, “Democracy Index 2023: Age of Conflict,” 2023.

↩https://freedomhouse.org/country/indonesia/freedom-world/2024

↩Power, Thomas and Eve Warburton (Eds.), Democracy in Indonesia: From Stagnation to Regression? Singapore: ISEAS (2020).

↩Power and Warburton (Eds.), 2020.

↩Rosseno Aji Nugroho, “Proyek Kebanggaan Jokowi Cetak Investasi Rp 375 T pada 2023,” CNBC Indonesia, 24 January 2024. https://www.cnbcindonesia.com/news/20240124095519-4-508530/proyek-kebanggaan-jokowi-cetak-investasi-rp-375-t-pada-2023

↩Mentari Puspadini, “Dituding Anies Punya Lahan 340 Ribu Hektare, Segini Kekayaan Prabowo,” CNBC Indonesia, 09 January 2024. https://www.cnbcindonesia.com/market/20240109110935-17-504039/dituding-anies-punya-lahan-340-ribu-hektare-segini-kekayaan-prabowo.

↩Muhammad Fakhriansyah, “Belajar dari Adik Prabowo, Begini Cara Punya Harta Rp 10 T,” CNBC Indonesia, 24 August 2023. https://www.cnbcindonesia.com/entrepreneur/20230824065457-25-465645/belajar-dari-adik-prabowo-begini-cara-punya-harta-rp-10-t

↩The Mining Advocacy Network. The long list included Titiek Soeharto, Luhut Binsar Pandjaitan, Lodewijk Freidrich Paulus, Wisnu Wardhana, Bobby Gafur Umar, Wahyu Sanjaya, Eric Thohir, Maher Algadrie, Ario Bimo Ariotedjo, and Airlangga Hartarto; https://pemilu.jatam.org.

↩Arianto Patunru, “Trade Policy in Indonesia: Between Ambivalence, Pragmatism and Nationalism.” Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 59, no. 3 (2023): 311-340.

↩Patunru, 2023.

↩Aditya Alta, et al., Modernizing Indonesia’s Agriculture. Jakarta: Kencana (2023).

↩Jeff Neilson, “Feeding the Bangsa: Food Sovereignty and the State in Indonesia,” in Arianto Patunru, et al. (Eds.), Indonesia in the New World: Globalization, Nationalism and Sovereignty, Singapore: ISEAS (2018).

↩

Filed Under