A pillar of Indonesia’s unprecedented economic growth over the last decade has been its ban on the export of raw nickel ore. This national experiment in downstream industrial policy began with the 2009 Mining Law signed by former president Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, which mandated the domestic processing of all commodities mined in the country. The export ban on nickel was only partially implemented in 2014 amid widespread opposition from the mining sector, and it came into full effect in 2020.

Before the ban, Indonesia predominantly exported raw nickel ore, which is minimally processed into nickel matte. The country’s nickel-related exports were a modest US$6 billion in 2013. By 2022, this figure had risen to nearly US$30 billion, propelled by the exports of higher value-added products such as stainless steel and battery materials.

Chinese firms that were large players in the downstream nickel-based production had no choice but to expand their operations within Indonesia to secure access to its abundant nickel resources. The rapid growth of the nickel sector was facilitated by direct investments under the Belt and Road Initiative. Chinese state-owned banks financed the construction of coal power plants and basic infrastructure, integral components of the industrial areas that fostered economies of scale and agglomeration.

The outcomes of these policies have been mixed. On the one hand, downstreaming has been relatively successful: tens of thousands of jobs have been created, higher-value skills have been transferred, and advanced technological and economic processes have been brought to Indonesia. No longer exporting raw nickel ore, Indonesian firms are now exporting nickel pig iron, ferronickel, and other nickel-based goods. Given that the value of Indonesia’s nickel exports has surged to five times the pre-ban rate, foreign firms are seeking partnerships with Chinese companies in order to establish more smelting facilities. Furthermore, inspired by the success of nickel, the government of President Joko Widodo, better known as Jokowi, is looking to ban the exports of copper and iron as well; in June this year, it passed a new ban on the export of raw bauxite.

The ban’s effects elsewhere have been less positive. It has created a market with few large buyers—an oligopsony, to disproportionately benefit firms with smelting capacity. These are mainly ventures between Chinese and Indonesian companies based in major industrial parks. As Indonesian mining firms earn less and less per tonnes of ore that they extract, they cut corners and costs. The improper dumping of tail waste, for example, raises grave environmental and health concerns for the surrounding areas. Extraction contaminates fresh water and emits particulate matter, whether from mines, power facilities, or vehicular runoffs. These emissions, which result from a complex interaction of chemicals such as sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides, can severely impact respiratory functions. Such problems have become prominent in Sulawesi—home to the country’s largest nickel reserves. With further export bans and industrial processing now on the agenda, health concerns are likely to spread to other islands, too.

Competing development models

Writing in the 1950s, political economist Albert Hirschman argued that balanced national economic development required the creation of complementary economies, a process that entailed generating demand for other goods, inducing investments with multiplier growth-effects, and protecting vital sectors from inward and outward shocks. In doing so, they create forward linkages with sectors that need further investment and backward linkages with founding industries. Hirschman’s strategy contrasts sharply with that of economist Arthur Lewis, who argued in the same decade that states should increase revenue and employment by attracting investment from foreign firms. Eventually, this is expected to move the domestic economies of the global South from subsistence into manufacturing or services. While Lewis’s dual economy long predates the policy prescriptions of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund in the 1980s, the theory characterized policymaking across these and other international organizations.

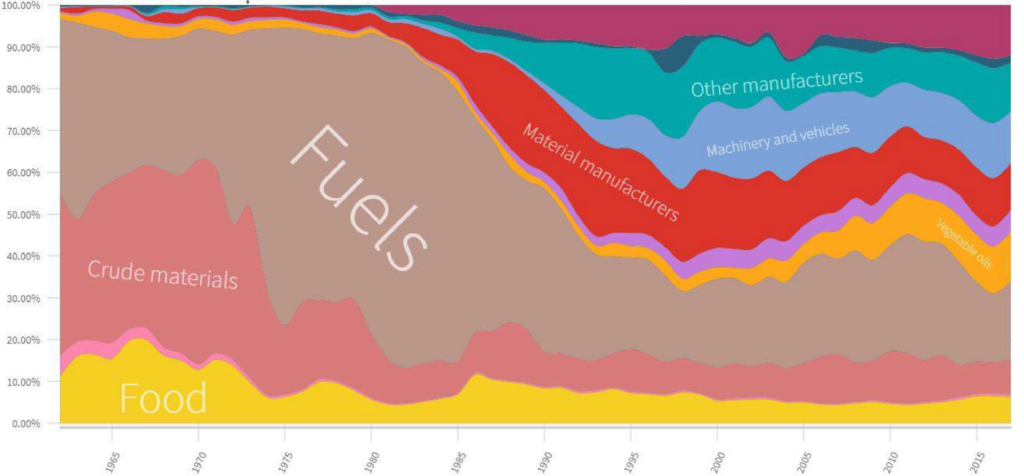

Like many other global South countries, Indonesia has followed a development path that combines Hirschman’s leading sector strategy and Lewis’ dual economy model, with preferences shifting over time. Under Dutch colonial rule (1816-1941), Indonesia exported coffee, coconuts, sugar, and other crops. Much of the country was divided among Dutch firms that exported raw produce for manufacture elsewhere and sale on the global market. After independence, in the late 1950s, under President Koesno Sosrodihardjo, better known as Sukarno, the Partai Demokrasi Indonesia Perjuangan sought to move the country from exporting resources to pursuing higher-value activities on the world stage. Sukarno nationalized foreign companies, enhanced financial support to state-owned enterprises, and implemented foreign exchange control policies. But despite the political elite’s longstanding stress on industrial policy, dependence on resource exports for foreign reserves has constrained the Indonesian government’s will and ability to encourage industrial growth at home (see figure 1).

When Suharto’s authoritarian government gave way to the reformasi in the late 1990s, Indonesia changed tack. Under pressure from international institutions, the government liberalized markets and deregulated the economy, increasing both private-sector participation and state support in certain sectors like energy and infrastructure. When Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono (SBY) came to office in 2004 in the midst of political and economic crises, he accepted many of these market principles, along the lines of Lewis’ dual economy model. Embarking on his second term in 2009, however, he returned to the economy to a state-interventionist model, which has only been strengthened since Jokowi came to power in 2013.

A changing global arena

This break with the dual-economy model was made possible by a changing global context, most saliently, with China’s emergence as a major global capital exporter. (In 2018, China’s foreign direct investment (FDI) stock totaled $3.8 trillion, and it spent around $843 billion in concessionary and non-concessionary financing between 2000 and 2019.) Since the 1990s, the PRC has increasingly oriented its development finance towards soft infrastructure and low value sectors to prevent recipient countries from rising up in the production chain. Politically, China has allied with global South countries in resisting the Western bloc, positioning itself as a model to emulate through the construction of large-scale physical infrastructures. In the face of Western pressure, China has become a major source of military aid; it is now the fourth largest arms exporter in the world, selling weapons to Myanmar, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, and Thailand. This growing strength bears enormous consequences for competition among regional political elites, exacerbating ethnic and racial fissures within recipient countries, as well as geopolitical tensions beyond the great power rivalries seen in headlines.

The Indonesian government has long encouraged the onshore smelting of nickel, but the policy took years to come to fruition. In the late 1990s, smelting licenses were extended to domestic firms, but these proved costly. Besides, enormous amounts of capital were needed to purchase the technology needed to begin operations and then scale them up to profitability. The government only funded twenty-six small-scale smelters with loans. At the same time, foreign and domestic investments in exporting nickel ore continued to increase. This situation frustrated the political elites who wanted to bolster industrial policy and increase downstream activities.

In 2009, the Tsingshan Group from China’s Zhejiang Province showed interest in investing in Indonesian mining, as a way to secure access to mineral concessions in the longer term. Tsingshan was the world’s largest producer of ferro-nickel and the second-largest manufacturer of stainless steel. The SBY government pushed Tsingshan to instead invest and develop an industrial park, moving the smelting activities from China to Indonesia. To do this, Tsingshan worked with the Bintang Delapan Group, a long-term partner of the Chinese firm and one of the largest nickel mining companies in Sulawesi. The new park was to be located at Morowali Regency in Central Sulawesi Province, covering 5472 square kilometers, which is estimated to hold 370.59 million tons of nickel reserves.

Construction for the park began in 2014. While industrial parks and special economic zones exist throughout Indonesia, there has never been a park in the mining sector that links extraction-to-smelting so easily, and at such a large scale. Tsingshan group owns 66.25 percent of the park and Bintang Delapan holds a 33.75 percent share. Spanning 2,000 hectares of land, the park holds smelting facilities and a transportation network. It also boasts a five-star hotel for investors, barracks for thousands of workers, major roads, a port, and a small airport. By 2019, sixteen major firms—including from Australia, Japan, and Korea—were operating there in activities such as battery production and carbon steel development. Adjacent to Bintang Delapan’s mining concession, one of the largest in Sulawesi, the Morowali Industrial Park (IMIP) has succeeded by bringing together smelting and extraction in a single location. Together, Tsingshan and Bintang Delapan established Sulawesi Mineral Investments, which has bolstered extraction by pouring capital investments into new mining technologies.

Since the facilities at IMIP are offshoots of existing ones in China, Chinese workers were recruited to take up supervisory, technical, and managerial roles. With the Indonesian government’s encouragement, however, IMIP soon began investment in nearby vocational schools with the goal of upskilling Morowalians, in turn providing jobs to locals and supplying IMIP a relatively cheaper supply of workers than what they would have contracted from China. In total, the company has thus far employed— directly and indirectly—80,000 Indonesians, the majority of whom come from Sulawesi or neighboring islands. In addition to schools, the IMIP constructed mosques and established health clinics.

With the success of IMIP, more firms are looking to invest in Indonesian nickel. The Weda Industrial Park (IWIP), built on the same model as IMIP, has become the largest nickel smelter in Weda, North Maluku. The Brazilian firm Vale, one of the largest nickel mining companies in Indonesia, has signed partnerships with Chinese firms Taiyuan Iron & Steel Co. Ltd. (Tisco) and Shangdong Xinhai Technology Co. (Xinhai) to build new smelters. Tsingshan played a major investor role, inspiring both imitation and competition from other Chinese and foreign mining companies. Indonesian smelting firms are worried that the scale of mining-smelting activities will result in decreased supply. IMIP and other smelting firms have started importing ore from the Philippines, the second largest nickel ore exporter in the world.

The cost

With the government’s export ban, Indonesia’s mining companies have been obliged to sell their nickel domestically, rather than to the highest bidden in international markets. National strategy on nickel smelting has led to a boom for industry, but it has also incurred important economic, political, and social costs. First, the export ban has created a nickel mining oligopsony, privileging the buyers of nickel minerals over sellers. Since Indonesian mining firms cannot sell extracted low- or high-value nickel to the overseas market, they are left with no choice but to sell on the far smaller domestic market, giving power to the select number of buyers. Among the buyers, two Chinese nickel smelting firms and their domestic Indonesian counterparts comprise 80 percent of the domestic market; only they have the productive capacity, thanks to Chinese financial support. IWIP will likely take a bigger share of the domestic nickel market in the future. Contained to this oligopsony, the price of nickel has been kept low, hovering between 15 and 30 percent of global market price. Mining firms, which need to sell their extracted nickel to pay their investors, firms, and service costs, have had no choice but to acquiesce to these extortionary prices.

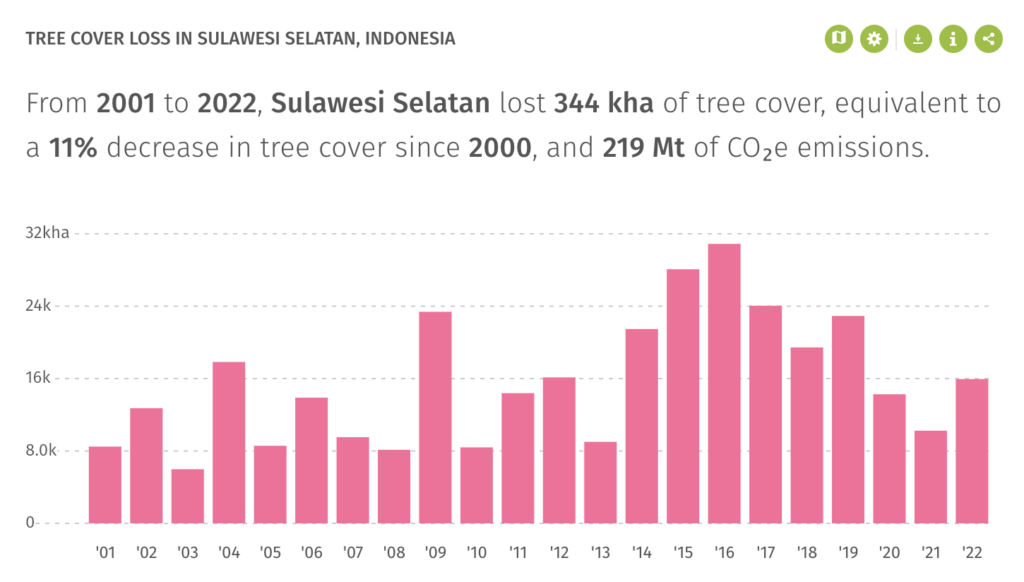

Thanks to these market effects, mining firms have been prompted to cut corners, with often severe impacts to surrounding communities. The disposal of mineral tailing has become a major issue, with firms illicitly dumping their mineral waste in the sea or in open pits.1 Another adverse effect is that nickel extraction has been significantly scaled up in an effort to compensate for dwindling prices—leading to deforestation to make way for open-pit and deep-pit mines (see figure 2). Mass deforestation means that Sulawesi’s periodic rains are more and more devastating. In 2022 alone, there were twenty-one floods and mudslides just on Sulawesi. This stands in contrast to the record before the implementation of the export ban; between 2005 and 2008, the island flooded only two to three times a year.

Beyond the environmental effects, the expansion in nickel production has meant more wage suppression throughout the country, and particularly in Sulawesi. This has taken the form of extending the working day as well as of relying on part-time workers who receive little-to-no protection from the national or local authorities. Fisher folk, who rely on the fishing stocks in the surrounding areas, have been affected by the illicit tailings deposit. Indonesians with alternative forms of livelihood in farming or tourism have no choice but to work with the mining sector. Many have migrated to the Morowali and Kendari area for jobs.

More export bans?

Despite owners and investors of nickel mining firms lobbying against the ban, the Jokowi government has withstood the pressures because the Indonesian oligarchy has no major investments in the nickel mining sector. While externalities continue to pose problems, the government insists that these are the inevitable costs of pursuing higher-value industrial activities.

The Indonesian government has signaled that its future policy will focus on the forward linkages of nickel smelting. Minister of Investment Bahlil Lahadalia said that the government will likely prioritize firms who plan to put Indonesian nickel in the service of domestic electric vehicle battery production, as well as smelters that rely on green energy. Government officials recognize that the country’s high-grade nickel reserves will run out within the next two decades, further underscoring the need to develop industry beyond smelting.

Nonetheless, the government’s success in the nickel sector has inspired confidence in similar strategies for bauxite. Indonesia is the sixth-largest producer of bauxite in the world, and there are currently four domestic bauxite and aluminum smelters, which produce 14 million tonnes of refined bauxite annually. In June 2023, the Indonesian Bauxite and Iron Ore Companies Association, which represents twenty-eight bauxite mining companies, voiced their protest of the ban. But replicating nickel’s success will be challenging: a bauxite processing or smelting facility costs $1.3 billion, which is three times more than a nickel smelter.

While the government stayed its decision to implement an export ban for copper and iron, these are likely to be implemented further down the line. A strange coalition of often conflicting actors—opposition politicians, mining firms, labor groups, environmental non-governmental organizations, and villagers in kampungs—stands to lose out in this future wave of export bans. As Karl Polanyi argued in The Great Transformation (1944), the commodification of land, labor, and money displaces groups that do not typically align with one another. But a very specific set of beneficiaries—Chinese smelting firms and their Indonesian partners in Sulawesi—have been empowered at their expense. Export bans and their mineral investments are large-scale, technology-advancing, and capital-intensive, helping to burnish the government’s legitimacy. This has enshrined a near-consensus among Indonesian political elites around the importance of smelting and value-added upgrading, which has these sectors to determine the nation’s industrial policy.

In January 2020, two nickel mining companies sought to acquire a permit from Indonesia’s Coordinating Ministry for Maritime and Investment Affairs to use deep-sea tailings. The Widodo government has previously given gold and copper mining companies the right to use DSTD, but nickel firms have not been accorded such rights. As such, the request has simply been to level out what has been given to other mining firms. The Widodo government refused the request claiming that nickel is far more destructive than gold or copper to the sea. Mining firms generally prefer DSTD due to the cost effectiveness of the solution. Storing tailings on a dam, which has been the traditional way to deal with tailings, is the more costly option due to the need to negotiate land and space with communities. While mining firms claim that this process of deep-sea tailings disposal (DSTD) is safer than the alternatives, research has been scant.

↩

Filed Under