Next week, a couple of dozen heads of state—from countries including China, Brazil, Indonesia, and almost a dozen African countries, among them Kenya, Zambia, and Senegal—will gather in Paris for the Summit for a New Global Financing Pact. Instigated by Barbados prime minister Mia Mottley and French president Emmanuel Macron at last year’s COP27, the event is aimed at the reform of the global financial architecture so as to “build a new contract between the countries of the North and the South.” Those who won’t be in attendance, however, include Joe Biden and Narendra Modi, who will instead be in Washington, likely announcing a North-South deal enabling General Electric fighter jet engines to be co-manufactured in India by Hindustan Aeronautics.

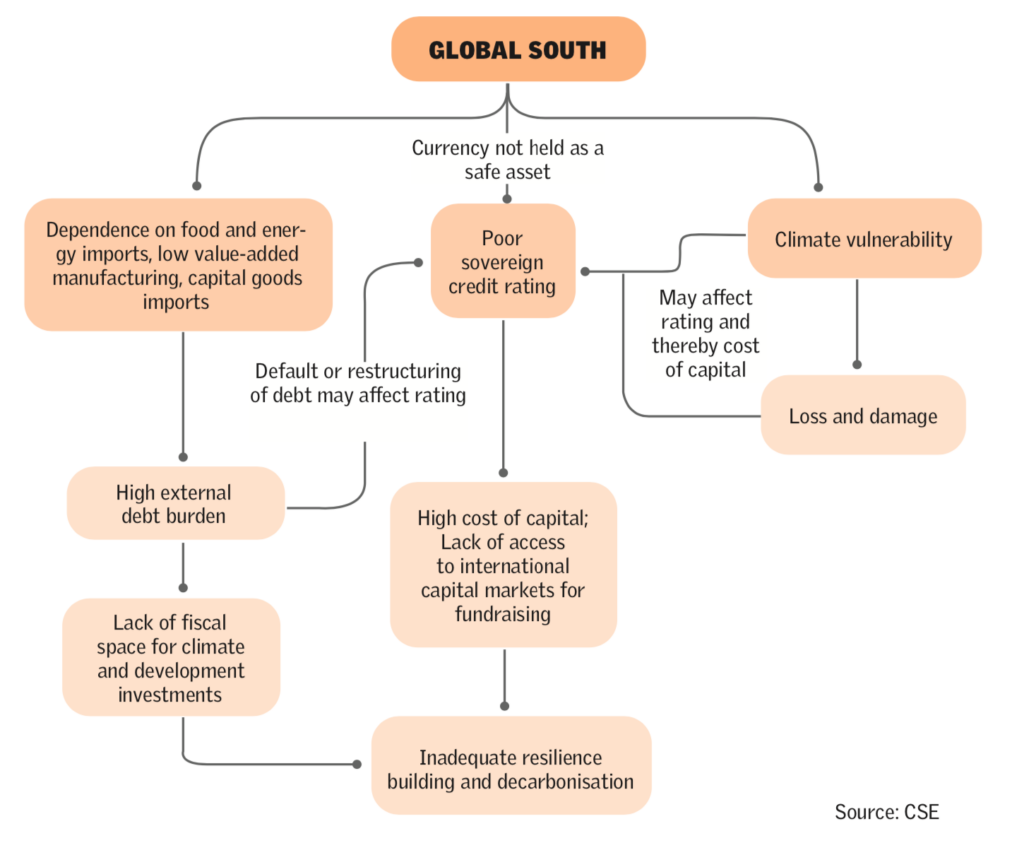

The declaration of a “New Washington Consensus”—the term given to the US’s renewed industrial strategy and its geoeconomic implications, elaborated by National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan in an April speech—by the Biden administration has faced opposition from Europe and other allies. US officials have in response invited them to not complain about protectionism and instead try the same measures. The investment-first approach to tackling the energy transition is possible for wealthy countries whose governments manage to find the political will. Middle income countries might be able to mimic the new industrial policy to a degree; nickel processing in Indonesia, or the development of EV and battery technology in India are two examples of such attempts. Smaller, poorer, and more vulnerable countries, however, have limited options when capital markets are shut, interest payments shoot up, and currencies devalue.

In a striking speech last month, former US National Security Council official Fiona Hill acknowledged that “the Rest”—the middle powers or swing states—were rebelling against the West. With unusual frankness, Hill depicted global South governments’ disinterest in the war in Ukraine—subject of much hand wringing in the North—as “less a cohesive movement than a desire for distance, to be left out of the European mess.” “The Cold War-era non-aligned movement,” Hill advised, “has reemerged” and developing countries don’t want to be “caught in a titanic clash between the US and China.” She cited an unnamed Indian interlocutor asking, “where are you when things go wrong for us?”

Those countries that were quick to respond in unity to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have been much slower to attend a summit addressing developing nations’ concerns about finance. Although invoked as a “key moment” in the G7 communique from Hiroshima last month, so far Germany and France are the only two wealthy countries whose heads of state will attend. (British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak will be at a Ukraine conference in London.)

The great and the good

The proposals to be discussed at the Paris summit are technically intricate and politically complex. Any agents pushing for change—be they governments, technocrats, campaigners, or academics—are aware that ambition needs to be balanced with the question of political feasibility and effectiveness.

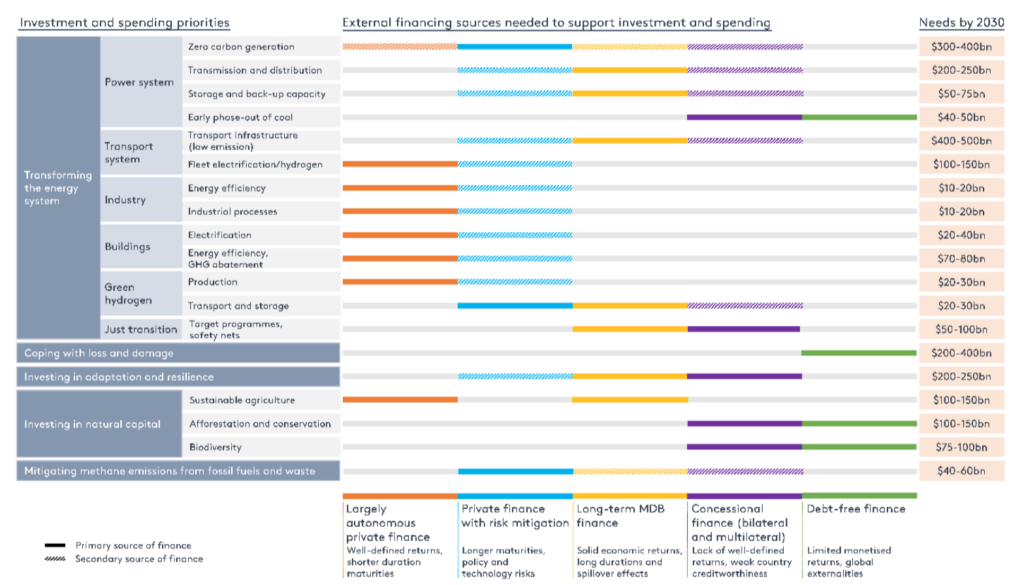

With a handful of countries in prolonged debt negotiations and another 61 nearing debt distress, urgency is high. Systemic reform of the international financial architecture has been pursued for decades but with little progress. No real forum exists, for example, for countries that run into debt repayment problems to work out a procedure with creditors. (Efforts to introduce such systems in 2002 and 2015 both failed.) Progress on reform of the global tax system has so far produced an imperfect floor, whose coordination is dominated by wealthy countries. IMF governing quotas remain skewed towards advanced economies, and the flawed system of sovereign credit ratings continues. The World Bank and its peers tend to lend on a project basis and the IMF continues to prescribe austerity measures for countries in urgent need of its liquidity support. Reforms at the World Bank allowing for an increase in its lending have so far yielded an additional annual $5 billion—a miniscule figure compared to its $240 billion of outstanding loans, and smaller still against the $1 trillion of annual finance that is needed each year to meet development and climate goals.

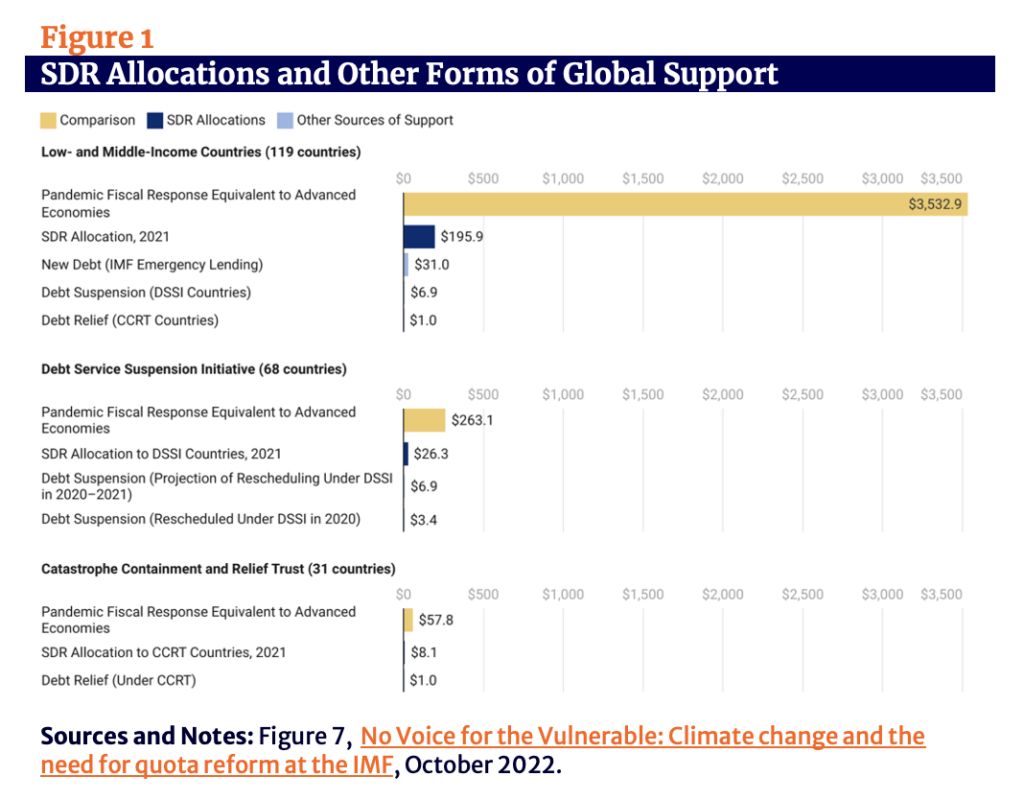

Even the most modest of proposals, involving little to no cost to rich countries, have been met with resistance. For example, one “announceable” outcome being floated for the Paris summit is to confirm the rechannelling of $100bn worth of Special Drawing Rights, an IMF-issued reserve currency, which was already promised by wealthy countries to poorer countries.

IMF rules mean that most SDRs are disbursed to the wealthiest economies. Many middle- and low-income countries quickly spent much of what they received to pay down debts and support domestic budgets, and so are in urgent need of funds, but rechannelling must be done in a way that satisfies both IMF rules and legal requirements in each country. Last year the Fund created a new facility, the Resilience and Sustainability Trust, to receive “rechannelled” SDRs from wealthy countries and distribute them to developing ones. While the RST has some novel features—longer term lending, and eligibility for middle- as well as low-income economies—it requires countries to be in an existing IMF program with the attendant subordination to IMF policy guidance that that entails. In any event, the RST can’t absorb the full $100 billion earmarked for rechannelling. Even when the Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust (the only other eligible IMF facility) is accounted for, some $37 billion worth of SDRs pledged for rechannelling will need to find a mechanism for distribution. The ECB insists that its own rules prevent them from rechannelling its SDRs into alternative facilities, such as multilateral development banks, even while detailed proposals exist to circumvent this problem.

Some items on the agenda exhibit ambitions greater than simply meeting existing commitments. Among these is a proposal for the widespread adoption of natural disaster clauses in sovereign bond contracts, which would automatically suspend debt repayments in event of major catastrophes such as pandemics or hurricanes. This, too, should be relatively easy to implement; Barbados, Granada, and the Bahamas all include such clauses in the bonds they issue, and a model clause has been developed by the International Capital Markets Association. But there’s little sign that rich countries will compel their financial firms, or even their official lenders, to adopt such clauses.

Elsewhere, there is some ambition for debt relief on a large scale, reminiscent of the publicly-backed HIPC program in the 1990s. As a key pillar of its Bridgetown agenda, Barbados has put forward a proposal for a mechanism to reduce the costs associated with foreign currency risk for investing in developing countries, and thus make borrowing cheaper. A working group convened by the Élysée has canvassed an application of the “polluter pays” principle to compensate for climate damages. The formal agenda includes a global tax on fossil-fuel extraction to support the rising losses associated with climate change in poor countries, which could raise $150 billion, and a shipping-fuel tax that would raise $40–60 billion annually; while debt campaign groups advocate for a 5 percent tax on multimillionaires that could raise $1.7 trillion a year. Though it often goes unmentioned, the US Congress raised revenue for the IRA by similarly taxing rich Americans and polluters.

Political space

Before the debt ceiling debacle took center stage, a top priority for the US Treasury had been reforming the World Bank. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen affirmed that the Bank should lend more generously and take climate more seriously. She also suggested that the Bank could take a broader view beyond discrete projects, acknowledging that “some of the ideas… will be easier to implement. Some will be harder.”

The United States, with its veto vote in the Bretton Woods institutions, could in theory push through many of the proposed reforms and amendments. The new World Bank president, Ajay Banga, is an American appointee, as convention dictates. (A European traditionally heads the IMF.) But with US elections set for next year, the Biden administration is reluctant to take any action that might be seen as handing out money to developing countries.

Yellen, who will attend the summit in Paris, testified this week before Congress that the IMF and World Bank were strategically important to the US. “These investments will bolster our engagement in these regions at a time of geopolitical competition,” she argued, making a case to proceed with rechannelling SDRs and to boost involvement with other IMF programs. The Republican party, which controls the House committee on Financial Services where Yellen testified, is unlikely to be moved. The GOP has a simpler reform of the Bretton Woods Institution: “don’t ban fossil fuel investments, stupid.”

The demands of domestic politics are not only a constraint for the global hegemon. India does not want China to be the champion of the South. Narendra Modi referred to the “global South” for the first time in a summit with 125 developing countries in Delhi. Though not facing any debt distress itself, India used its presidency of the G20 this year to launch a Global Sovereign Debt Roundtable with the IMF and the World Bank. The group aims to address the process for sovereign debt restructuring, and all creditor groups are represented including bondholders and China.

But given national elections in 2024, Modi is looking for quicker bilateral deals with the US that will play to jobs and industrial indigenization at home. Technology transfers of US fighter jet engines and chip fabs to be co-manufactured in India have proven more appealing than wading through the morass of an international reform agenda.

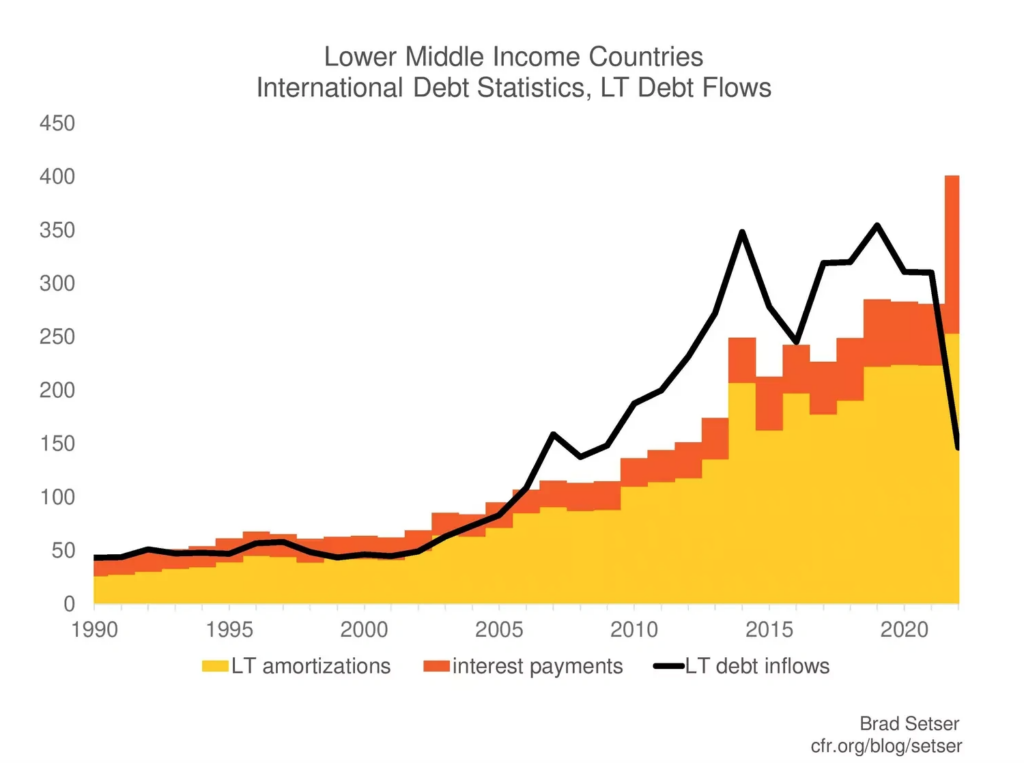

Meanwhile, since interest rate hikes in 2021, low- and middle-income countries pay more in interest payments than what they would need to spend annually to achieve their national Paris agreement climate action plans. Financial hardship is on the rise, with half of low income countries in or at high risk of debt distress. At the Paris summit, even modest proposals for incremental solutions have to garner significant support to navigate the scarce and narrow avenues for change. The wildfires billowing smoke across North America are a reminder of our shared destiny; the mix of ballooning debt payments, hunger, blackouts, and political instability are no less incendiary.

Filed Under