Credit in Brazil—and particularly consumer credit—is expensive, but ubiquitous. Exclusion from the credit market, where basic needs not covered by wages are increasingly financed, is now a threat to the very social reproduction of the working classes. Accordingly, the massive expansion of access to banking services, known as “financial inclusion,” has made working-class and poor Brazilians key players in the creation of financial wealth—the indebted counterparts of a booming creditor ecosystem.

Over the last few decades, there has been an accelerated and continuous increase in the number of people in debt and the amount of disposable household income spent paying it off. According to the Central Bank of Brazil,1 at the end of 2020 there were around 85 million people in debt to the financial sector, roughly 46 percent of the adult population, with just over 8 million designated as “at-risk debtors.”2 Nearly 9 million have defaulted.

In the wake of the Covid-19 crisis, the situation has continued to deteriorate. While the number of borrowers expanded at the expected rate, surpassing 105 million people, the number of people in risky debt has practically doubled—reaching 15.1 million in March 2023.3 An attendant explosion in defaults has taken place, affecting tens of millions of people who together carry debt worth R$350 billion (US$70 billion).4 Meanwhile, the debt poor5—those who fall below the poverty line due to the amount of income lost to loan payments—are another growing part of the increasingly complex landscape of Brazilian inequality.

The scope and impact of this problem affects millions of lives and, by inhibiting the consumption of working families, acts as a brake on the reheating of the domestic economy. Looking to address the urgency of the situation early in his third term, in July 2023 President Luis Inácio Lula da Silva launched an ambitious social program focused on debt renegotiation. Desenrola Brasil—“unroll” or “untangle” in English—offers conditions so that people who have been denied credit can renegotiate their debts, reduce their degree of financial vulnerability, and reestablish their creditworthiness. The program began as a campaign promise, but has become a lifeline for tens of millions of Brazilians who are in arrears.

It is also a lifeline for their creditors. The Central Bank acknowledged that the high leverage of household debtors, and the growing losses that this leverage imposed on the financial sector, had resulted not only in a retraction of the supply of credit to families, but also in a limit to banks’ profitability.6 The latter is explained by the fact that 65 percent of credit is in the hands of families, whose loan arrangements generate the majority of credit interest for the banking sector—73 percent—from consumer credit.

The aim of this article is threefold. First, to contextualize the development of chronic indebtedness among Brazilian families. Second, to situate and map previous public policy initiatives that, reflecting the power of creditors in the Brazilian economy and the acute crisis caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, have chosen debt as their object of treatment. And finally, to reflect on the implications of household debt becoming an explicit and institutionalized dimension of public policy with the creation of Desenrola Brasil.

From mass financialization (1995–2015) to the profitability crisis (2016–2021)

The process of financialization in Brazil began after the end of the “economic miracle” (1967–1973) and can be divided into two phases. The first phase, which we call “elite financialization,” took place from 1981 to 1994 and was marked by the context of the foreign debt crisis and rising inflation. During this phase, the banking system implemented indexing mechanisms that guaranteed financial gains for a small, privileged clientele. In these years, where income from financial securities grew, productive investment stagnated.

The second phase, called “mass financialization,” lasted from 1995 to 2015. This period saw a reduction in inflation and real interest rates, accompanied by a notable increase in credit operations. At the institutional level, this period was marked by a regime that reconciled the expansion of social policies—particularly cash transfers7—with the expansion of financialized accumulation. During these years, the country moved from a period of stagnation in productive investment, characteristic of the first phase, to the consolidation of a process of deindustrialization and low economic growth.

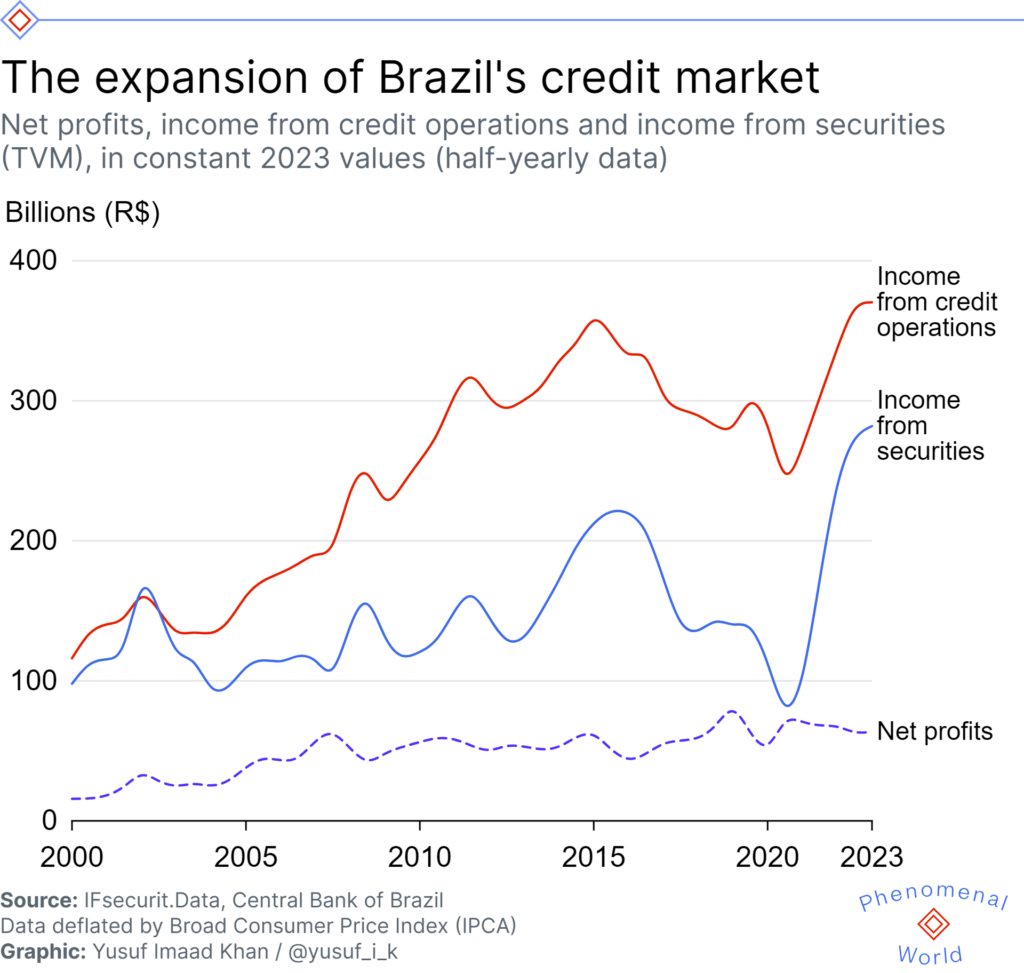

The expansion of the credit market in the second phase is visualized in the above chart, showing data from a representative basket of the financial-banking sector for the period between 2000 and 2023.8 The graph shows the variables net profit (dotted line), credit revenue (highlighted by the red line), and revenue from securities (or TVM,9 represented by the blue line). As illustrated, the financial-banking sector’s net profit, driven by credit and securities revenues, grew almost uninterruptedly. In the mass financialization phase, operations in the credit market overtook debt securities as the main source of growth. Unlike the first phase, in which the debt securities market was central, the increasing importance of income from operations in the credit market now stands out.

Against this backdrop, this section proposes an analysis from the perspective of financial cycles. To do this, we discuss two points: first, a fall in the two main banking revenue streams appeared as a trend before the Covid crisis and, for this reason, we can consider that decline to have a more structural dimension; second, the state played a key role in restoring the sector’s profitability.

Analyzing the period of the profitability crisis also reveals interesting characteristics. Given the decline in dominant sources of income from 2016 to mid-2021, the banking sector’s strategy to boost and stabilize net profit growth was based on increasing the margin applied to credit operations, i.e. the spread. The spread represents the amount effectively retained by the banking sector in credit operations, calculated as the difference between credit income and funding costs. In other words, the spread represents the banks’ reaction to the fall in revenues.10 Using their power in the credit market to increase their rents, banks transferred the burden of the crisis to borrowers.

Among borrowers, that burden fell mainly on households.11 The credit data show that at the end of 2016, for the first time in the historical series, the balance of credit to households surpassed that of credit to non-financial companies, and has remained dominant until the present.12 It is those households, therefore, and particularly those on lower incomes, who are bearing the brunt of the prohibitive interest rates.

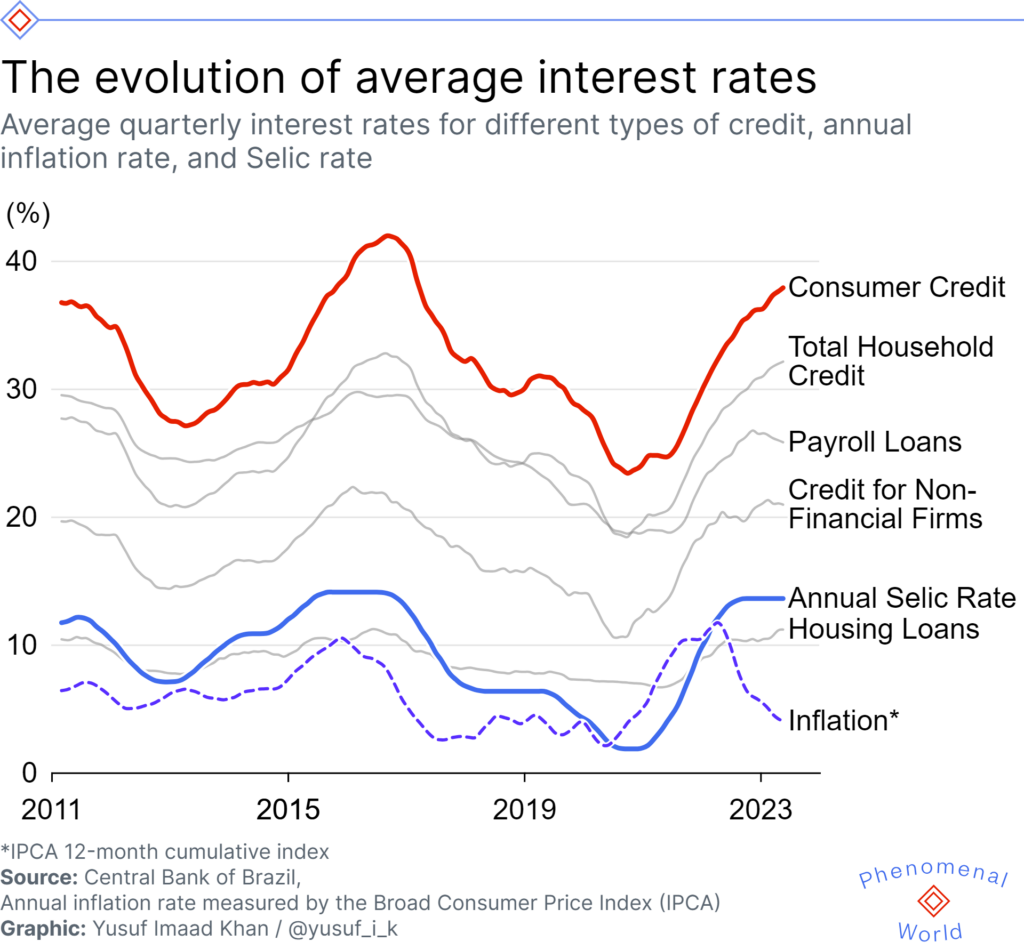

The above chart shows the recent evolution of the average interest rates charged by the financial sector, comparing the Selic rate and the IPCA.13 It highlights the centrality of the Selic rate in understanding how the banking sector’s revenues are recovering whereas household indebtedness is increasing. It is clear that, as of 2021, following the accelerated rise in the Selic rate, interest rates for common household credit registered a significant jump. Low-risk payroll loans rose on average from 19.98 percent per year in May 2020 to over 25.81 percent in May 2023, while free resources loans, which include all types of loans to families, moved from 25 to 38.22 percent per year on average over the same period. In May 2023, the month prior to the launch of Desenrola, with inflation at around 4 percent, the interest rate on the balance of loans to families was almost 7 percentage points higher than that on the total balance of loans.

On the credit supply side, as of 2012, 90 percent of new credit concessions relate to non-real estate credit, i.e. consumer credit, which is not used to accumulate assets as part of a risk prevention strategy.

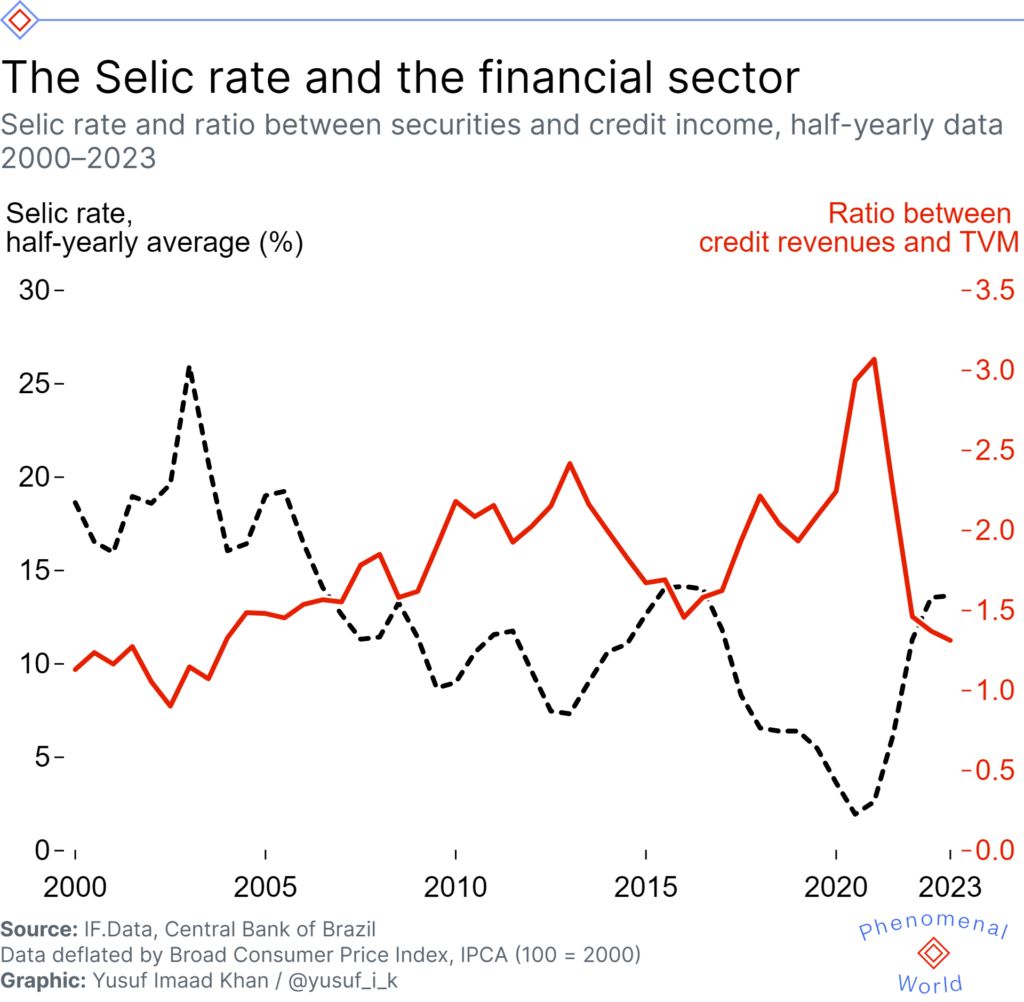

The Selic rate is also a crucial variable for understanding the expansion of the Brazilian credit market. This relationship can be seen in Graph 3 below. The ratio between securities and credit income (represented by the red line) shows a negative correlation with the nominal Selic rate (represented by the dotted line). This correlation indicates that the banking sector expanded its credit operations in line with changes in monetary policy: the more the Selic rate fell, the more the sector came to depend on credit income.

According to Graph 3, the lowest value of this ratio was more than 0.9 in 2002, when the nominal Selic rate was, on average, above 20 percent. A value of 1 indicates that the two incomes have the same weight for the Brazilian banking sector. The highest value recorded was 3.1 in December 2021, when the Selic rate reached a historic low (2 percent per year) and was negative in real terms. It is also worth noting that, with the increase in the Selic rate in 2022, the ratio returned to its 2004 level, reaching 1.3. With regard to 2021, as Graph 1 above shows, the year stands out for reversing the downward trends in both revenues. A very plausible explanation, based on a combined reading of the two graphs, is that the Selic rate played a crucial role in this reversal. Brazil’s monetary policy diverged from other central banks when, from 2021 onwards, the BCB prematurely adopted a contractionary approach and raised the Selic rate to 13.75 percent in August 2022, putting the country back at the top of the list of the highest real interest rates in the world.14 Only with the intervention on the Selic rate was the profitability of the financial-banking sector restored.

One interpretation of these developments supports the framework of a financial-rentier class coalition, whose preferences guide Brazilian monetary and fiscal policy decisions.15 It is possible to infer that a downward trend in revenues caused these actors to intensify rentier channels in the debt securities market, in favor of raising the Selic rate. In a situation of declining revenues, it becomes not only preferable but imperative for the financial sector to secure the state as a debtor, as opposed to budget-constrained families and firms.

It is in this context, of a financial cycle in a contractionary phase, and with the state playing the role of “revenue guarantor of last resort,” that the Desenrola program was born, interpreted here as one of the pillars for the inauguration of a new financial expansionary cycle.

However, before explaining the context that led to the creation and implementation of the program, it is worth examining the changes caused by the Covid-19 crisis and how they impacted the relationship between debtors and the financial system.

Covid-19 and the social crisis

During the coronavirus pandemic, which led to lockdowns and other forms of social isolation, emergency measures were adopted to alleviate the suffering of families and prevent companies from closing their doors or massively laying off their workforce. Unlike the Great Financial Crisis of 2008, the bailout of families prevailed as a centerpiece of global initiatives dealing with the economic, social, and health crisis caused by Covid-19. In all latitudes, various income and employment guarantee programs were implemented, with the common goal of giving cash to those unable to work, at higher levels than existing social protection systems could achieve.

Brazil was no exception, and it adopted a suite of ad hoc programs: emergency aid to people in situations of vulnerability; an emergency benefit for formal employees; an emergency benefit for maintaining employment and income; and emergency financing to cover payroll expenses. These emergency income guarantee programs consumed 63.5 percent of the “war budget” spent in 2020.16

The generous Covid tax relief packages laid bare the folly of the fiscal and monetary orthodoxy that had previously restricted public spending and reduced the redistributive and risk-mitigating power of social policies. After four decades of neoliberalism, austerity policies had dismantled the provision of public services, encouraging privatization and financialization in their stead. Chronic indebtedness is a symptom of this shift, a fact that became clear with another set of measures adopted during the Covid crisis: the temporary suspension of payments on household debt.

Debt suspension programs were necessary because of the explosion of private household debt that characterized the decade prior to the pandemic and that now comprises a considerable portion of households’ disposable income. As incomes dropped violently with the pandemic shutdowns, already record-high default rates ran the risk of spreading throughout the country’s financial system.

The United States, the United Kingdom, Argentina, Spain, Italy, and many other countries all adopted similar temporary measures—combining generous cash transfers with the temporary suspension of debt repayments and sanctions previously applied to defaulters or those in arrears. Once again, Brazil was no exception. In parallel with the implementation of Emergency Aid, which covered 67 million people for eight months, some debts were suspended, such as students’ debt with FIES, for example.17 However, the July 2020 law restricted this favor to debtors who were up to date with their payments or less than 180 days in arrears,18 and offered significant discounts to those who agreed to renegotiate their debt while the law was in force. No federal provisions were passed to suspend the payment of debts from mortgages, rents, or current account payments.

What we saw across national contexts in the midst of the Covid crisis was a sharp reduction in the occurrence of defaults. This happened by way of fiscal stimulus guaranteeing relatively high liquidity for families, and through debt payment suspension measures and other related administrative instruments, which stimulated a wave of debt renegotiation with clear leadership from private banks. The reduction in defaults and arrears was accompanied by an increasing credit balance that deepened the ties between households securing their consumption through debt and the financial institutions whose profits are guaranteed by that debt.19

In Brazil, the process of restoring families’ debt capacity took place outside of coordinated state action—in other words, it was the initiative of the banking sector itself.20 Thus, the most vulnerable families and workers covered by the emergency cash transfer program began to seek out banks to renegotiate their debts.21 Banks and other financial institutions spent around 60 billion reais (12 billion USD) on debt extension programs between March and December 31, 2020 without renegotiating interest rates, which at the time were in free fall.

With regard to the repayment of mortgage loans, the National Monetary Council recommended that financial institutions suspend mortgage installments for up to 120 days, later extending the recommendation to 180 days. This was aimed at borrowers who were in default or who were no more than two installments in arrears. There was no interest forgiveness, which continued to apply to the remaining installments. On the other hand, for borrowers of the housing access program Minha Casa Minha Vida,22 track one of which is 90 percent financed by public funds,23 it was necessary to pass a specific law to suspend these installments, not least because in December 2020 defaults of more than 360 days had already reached 33.2 percent of contracts. The bill (795/2020) passed the Chamber of Deputies, but is still being processed in the Senate. In the meantime, the percentage of defaulters over a year in arrears reached a record high in December 2022: 45 percent of borrowers in Band 1 of the program.24

Individual debts were handled on a case-by-case basis—meaning that they may not have been fully favorable to the debtor—leading to a reduction in the principal and interest rate. It is estimated that, during the Covid crisis, in a context of extremely high unemployment and rising levels of severe food insecurity, the option left to the population with “survival debts” was to ensure their ability to remain in debt in order to meet their most immediate needs.25 This indicates that “financial inclusion” has become the unavoidable material basis of social inclusion for a large number of households, even in the face of high financial vulnerability.

Debt renegotiation reappeared in 2023, but this time as federal public policy. Designed by the Ministry of Finance, Desenrola was marketed as one of the founding milestones of the Lula 3 administration.

Is Desenrola an ad hoc rehash of a successful one-off initiative implemented by banks during Covid-19, now with the participation of the state? Or is it meant to regulate the credit market in order to support a new cycle of financial expansion, and by so doing transform debt management into a full-fledged social policy?

A focus on defaults over debts

Victorious in the 2022 federal elections, the Workers Party brought forward the Desenrola Brasil bill in June 2023, which was voted into law in September with a large majority. The bill’s main objective is to open a channel for debt renegotiation between defaulters and institutional creditors (banks, financial institutions, and public service providers) under the tutelage of the state, in the form of guarantees.

Initially, the government planned to help up to 32 million people,26 restricting itself to those registered with credit bureaus who had defaulted on debts issued between 2019 and 2022. Given the very heterogeneous profile of debtors and defaulters, the program is structured into two bands. Band 1 targets 21 million defaulters with incomes not exceeding two times the minimum monthly salary, equivalent to R$2,824 (US$656)—encompassing the majority of borrowers (66 percent). Band 2, on the other hand, includes those with monthly earnings of above two times the minimum wage all the way up to incomes of R$20,000 (US$4,036), which corresponds to a potential universe of eleven million defaulters.

The legal framework means that, in Band 1, the state assumes a significant portion of risk: in the event of a repeat default, it guarantees the bank’s payment of the principal (stipulated after the debt has been renegotiated), adjusted by the Selic rate. For Band 2, the risk is entirely borne by the financial institutions. In contrast to Band 1, the incentive to renegotiate Band 2 is purely regulatory in nature: renegotiated debts generate “presumed credit,” reducing banks’ minimum capital requirements and providing greater liquidity. The renegotiation of Band 2 began in July 2023. Band 1 began to be serviced in September 2023.

In Band 1, renegotiation takes place through the Desenrola Brasil digital platform, accessed through a government portal. This platform was developed by the company PdTec with the aim of consolidating debts and strengthening the relationship between creditors and debtors. This company has know-how in the area of digital collections, working to recover defaulted debts through electronic summons. On the platform, creditor firms take part in an auction, offering discounts on the value of debts, which are defined by the creditors on a case-by-case basis. The liability for defaulted debts was initially estimated at R$150 billion (US$30 billion). According to the Ministry of Finance, the auctions organized by the creditors ended up facilitating the significant discount of R$126 billion (US$25.2 billion), reducing the defaulted debt to be renegotiated to just R$24 billion (approximately US$5 billion). The average discount was expected to be 60 percent, but ended up at 83 percent.

The program covers debts from consigned and nonconsigned loans, as well as nonbank debts. Debts secured by real guarantees or linked to rural credit, real estate financing, and operations involving third-party risk, are not eligible for renegotiation. In short, the program prioritizes consumer credit.

In Band 1, the state grants a guarantee exclusively to debts that do not exceed the R$5,000 (US$1,000) mark, in aggregate totaling around R$13 billion (US$2.6 billion). It’s expected that the main debts renegotiated will be those related to consumer bills, such as water, electricity, telephone, retail, and bank obligations. The rules offer the option of paying in cash or through bank financing, without the need for a down payment. Interest for Band 1 is a maximum of 1.99 percent per month, equivalent to an annual rate of 26.68 percent per year, with the first installment due after a maximum of sixty days. The minimum payment installment will be R$50 (US$10) and the payment term is between two and sixty months, with decreasing installments. In real terms, the ceiling for charging interest is high, which makes the renegotiated debt more expensive, since the IPCA stood at 4.68 percent in 2023. In 2024, inflation is expected to be even lower, at 3.25 percent.

The guarantee offered by the National Treasury comes from the Operations Guarantee Fund (FGO), a program originally launched in 2009, in the context of the Great Financial Crisis. In terms of the legal framework, therefore, the Desenrola Brasil FGO is nothing new, but it extends the existing framework from legal entities to individuals. The government initially made R$87.5 billion (US$17.50 billion) available to the National Treasury to make up the FGO for Band 1.

For debts addressed under Band 2, each financial institution has the autonomy to renegotiate through its own channels or together with its partners, in an approach similar to that adopted during the Covid-19 crisis. In order to participate in the program, individuals with debts that can be renegotiated under Band 2 must go directly to their creditor institution.

Unlike Band 1, Band 2 does not have a FGO or a digital platform, and the discounted debt is to be paid in cash. But given slow growth in demand, the government decided to review the rules for Track 2 and permit defaulted debt to be paid in installments. Regulatory incentives are offered to encourage financial institutions to increase the supply of credit for the program, while the incentive for the bank is that the value of the renegotiated debts generates “presumed credit.” As Minister Fernando Haddad explained: “If the discount for the person is R$7,000 (US$1,400), the [presumed] credit for the bank will be R$7,000 (US$1,400).”27 Therefore, when renegotiating debts, banks have a “presumed credit,” freeing up liquidity for investment.

To summarize the main differences between the structure and state backing of the two bands: in Band 1, there is fiscal support, namely the Operations Guarantee Fund (FGO), whose principal is covered by the Treasury and adjusted by the Selic rate in the event of default on the initial debt renegotiated; Band 2, meanwhile, encourages renegotiations via an accounting incentive, whereby banks gain presumed credit in equal value to the renegotiated debts.

With Desenrola underway, the federal government decided to extend its scope of action. Its target audience now includes MEIs (individual micro-entrepreneurs) as well as FIES-funded students in default, covering loans that were taken on up to 2017 and which were in default in June 2023—comprising about 1.2 million students. The channels for renegotiation are Banco do Brasil, Caixa Econômica, and the Ministry of Education (MEC), indicating that it is exclusively up to the government—the creditor of the student loan—to define the renegotiation rules, without requiring the participation of private institutions. Three different debt refinancing profiles were created, which can be paid in installments (from fifteen to 150 months), with different percentages of principal discount (ranging from 77 to 99 percent) or charges (100 percent). The path to refinancing depends on the condition of the debtor, whether they are registered with CadÚnico and/or a former Emergency Aid beneficiary, as well as their accumulated time in arrears.28

Unraveling knots

At the end of 2023, the Ministry of Finance acknowledged that the targets achieved by the program had fallen short of what had been planned. While about eleven million people across both bands had benefited (against estimates of more than thirty-two million potential debtors), only 1 million people (5 percent of the target audience) in Band 1 were able to renegotiate and pay off their debts, which collectively amounted to R$5 billion (US$1 billion). Under Band 2, 2.7 million people paid off debts of R$24 billion (US$4.8 billion) through direct negotiations with financial institutions. By the end of 2023, R$29 billion (almost US$6 billion) had been renegotiated. The same occurred with Desenrola FIES, with only 14 percent of defaulting students having renegotiated their debts by the end of December 2023.29

But the seven million people who were taken out of the default list via Desenrola were registered as defaulters with debts of less than R$100 (US$20). Forgiveness for these small sums was off the table—debt is to be paid, whatever the amount and whatever the conditions that led to it. By way of illustration, it is worth pointing out that the renegotiation of the individual debt of R$100 (US$20) of seven million defaulters, if maintained in full without discount, would correspond to a maximum of R$700 million (US$140 million), which represents just 0.2 percent of the total credit revenue obtained by banks in 2022, according to data recorded by the Central Bank.

With the program still under development and subject to adjustments, and which has already been extended twice, a full accounting of its impact would be premature. But some crucial elements can still be assessed—starting with the justifications for a federal government program to reduce defaults.

The resumption of growth is a primary objective of the third Lula administration, and credit to families appears to be a crucial strategy in pursuit of that goal given the existing policy framework. In 2023, Congress approved the New Fiscal Framework (NAF), which consists of new rules for public spending. In short, primary public spending (excluding interest payments) can only grow up to 70 percent of the previous year’s tax revenue. If this growth reaches above 3.57 percent per annum, an additional clamp is imposed on public spending, limited to an annual real increase of no more than 2.5 percent. Health, education, and social security spending are exempt, in compliance with the Constitution, but other social spending will likely be heavily repressed to meet the requirements of the NAF.30 As Pedro Bastos has pointed out, if this rule is not complied with, “the punishment is for spending to grow the following year at a rate 50 percent lower than the rate of revenue growth.”31 Within this framework of fiscal austerity, in which the lever of growth can only be wielded by private capital, maintaining demand becomes even more heavily dependent on household consumption financed by credit.

The other flagship policy of the administration is the New Industry Brazil (NIB), a policy launched in January 2024 to reverse the process of reprimarization of the economy by fostering a cycle of reindustrialization. It will take time for the resulting productivity gains and raised wages to appear. In the meantime, massive household indebtedness will compensate for the absence of public investment, fulfill the expected transition to a virtuous cycle of growth with rising real wages, and, by expanding the credit market, boost the optimism of private investors.

Therefore, cleaning up a situation of extremely high default rates is a task for yesterday. Not least because, if, as the Finance Minister says, the resumption of growth will be based on public-private partnerships (PPPs), we need to reduce the risk that household defaults may jeopardize the prevailing development financing model. Reducing defaults without tackling indebtedness in some way reflects a de-risking strategy, insofar as it ensures that, via loans, families are able to pay for the services charged by private investors in the event that family income does not cover all needs. These are mostly institutional investors, operating in the area of social and urban infrastructure, notably health, energy and sanitation. In these sectors, the price of consumer tariffs tends to increase in real terms to ensure a good return on investment.

But the causes of default remain unaddressed. Desenrola has failed to offer mechanisms to protect families from chronic indebtedness, which today amounts to approximately R$3.5 trillion (US$670 billion or 32 percent of GDP). While the sum may seem low in comparative terms, it is worth noting this is debt taken on for short-term consumer needs—to finance basic social reproduction.

It’s worth remembering that, in 2021, following strong mobilization by consumer protection bodies, a law was passed to establish an extrajudicial legal framework for renegotiating debts. It covers the same debt profile covered by Desenrola—debts related to consumption or linked to financial institutions—but its target audience is over-indebted people, regardless of whether they are in default. Eligibility is extended to anyone in good faith who has accumulated what debts are necessary to meet their basic needs and does not have enough income to pay them off without compromising what the program calls an “existential minimum.” The minimum acts as a safeguard, stipulating that the monthly payment of debts cannot compromise more than 35 percent of the over-indebted person’s income. The law also includes criteria that financial institutions must observe, such as preventing abusive practices when granting credit and collecting debts that could threaten vulnerable social groups.

The Over-indebtedness Law was not enough to reverse, over two years, the spread of overindebtedness. But the federal government scored a goal by inserting into the Desenrola law a cap on the repayment of credit card debts. Under the law, accumulated interest cannot exceed the principal, putting an end to outrageous percentages that reached interest rates above 430 percent per annum at the end of 2023. This is an important step, even as it exemplifies the same logic that has stimulated family indebtedness as a driver for rentierism, as removing the threat of default is essential to the stability of the financial system.

The idea of making the Desenrola program permanent, as has been announced, offering a legal framework for renegotiating defaulted debts for low-income families, suggests that FIES Desenrola may also be here to stay, considering that a new expansion of FIES to finance access to private and paid university education is already on the table of the Minister of Education. The Minister of Entrepreneurship, Micro-enterprise and Small Business, would also like a Desenrola to call his own. In whatever new forms it takes, this program represents the adoption of an unprecedented institutional and legal framework for debt management via public policy, rearticulating the relationship between the government and financial institutions, while placing family debt at the center of current attempts to restructure the Brazilian economy.

The government has renewed the program, from December 2023, to March and now May 2024, for those covered by Band 1. Similarly, in order to reach more debtors who have not rushed to make use of the program, the government made access to its digital platform more flexible through partnerships with the post office, additional financial institutions, and companies like Serasa—a private consultancy, credit granting, and debt recovery firm which has built a national reach by lending at exorbitant rates to those excluded from formal credit. With these expansions, coverage has improved, but barely hit 50 percent of the target population. According to the most recent figures from the Ministry of Finance on the program, up to mid-March of this year, about 14 million people across both Bands 1 and 2 have renegotiated R$ 50 billion in debt. It remains to be explained why this ambitious, highly-publicized program has failed to attract the poor, defaulting population it was designed for, and who seem indifferent to their debts.

In this way, the government’s claim that Desenrola would reconfigure the frameworks of social policy by easing the burdens of defaulters loses its strength. What was the amount previously paid as debt service before the default, and what criteria did the financial sector adopt for discounts and auctions? How did the government act so that, in addition to defaulters, highly indebted Brazilian families could escape the spiral of persistent debt refinancing in order to survive? In place of answers to these fundamental questions, there seems to be a functional strategy that supports mass consumption via indebtedness for the purposes of rentier accumulation. The novelty lies in the fact that the state is taking on debt management as a way of confronting the contradictions that rentier accumulation itself engenders—thereby turning debt management into a novel dimension of social policy.

Financialization in Brazil is advancing by searching for profitability in the public debt securities market and in the credit market, depending on what is most lucrative. This status quo has a new partner in Desenrola Brasil. In twenty years, Brazil has gone from a society without much credit to a nation where debt rollover is part of the struggle for survival—a trend that, by the looks of things, is here to stay.

This article was translated from Portuguese by André Lucena.

Central Bank of Brazil, “Financial Citizenship Report,” Cidadania Financeira, Brasília (2021).

↩In Portuguese: “endividados de risco.” According to the Central Bank (2023), the risk is characterized when two or more of the following criteria are present: i) default on payment of the credit installment; ii) monthly income commitment to pay debt services of more than 50 percent; iii) monthly disposable income after paying debt services below the poverty line; iv) when debts with overdrafts, personal credit without consignment, and credit card revolving credit prevail.

↩Central Bank of Brazil, “Financial Citizenship Report,” Cidadania Financeira, Brasília (2023).

↩“Map of Default and Debt Negotiation in Brazil,” Serasa, https://www.serasa.com.br/limpa-nome-online/blog/mapa-da-inadimplencia-e-renogociacao-de-dividas-no-brasil/.

↩Costa, Pedro Rubin. Pobres por dívida: o endividamento familiar e as estatísticas de pobreza entre 2008 e 2018 – uma análise a partir da Pesquisa de Orçamentos Familiares. Rio de Janeiro: Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, 2023. (Dissertação de Mestrado).

↩Central Bank of Brazil, “Financial Citizenship Report,” Cidadania Financeira, Brasília (2023).

↩See Lena Lavinas, The Takeover of Social Policy by Financialization: The Brazilian Paradox, (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017).

↩Methodologically, we followed Mader (2023): we collected accounting data for the financial sector from the Central Bank of Brazil’s IF.Data system; these are income statements and quarterly reports from which we calculated the half-yearly figures. The business category called B1 was selected to represent the sector, including commercial banks and multiple banks with commercial portfolios. The B1 category represents approximately 70 to 85 percent of the financial sector’s total net revenue, depending on the year, and is analyzed as a continuous series. The historical series have been deflated by the Broad National Consumer Price Index (IPCA).

↩TVM are securities, both public and private, with the latter being indexed on the Selic prime rate.

↩Bruno Mader, “The Rentier Behavior of the Brazilian Banks,” Brazilian Journal of Political Economy 43 (2023): 893-913.

↩Lena Lavinas, Lucas Bressan, and Pedro Rubin, “Brazil: How Policies to Tackle the Pandemic Have Ushered in a New Cycle of Family Indebtedness. Brazil in Global Hell: Capitalism and Democracy Off the Rails. Organizers: André Singer, Cicero Araujo, Fernando Rugitsky (São Paulo: FFLCH/USP, 2022): 249-292.

↩At the start of 2011, loans to households totaled 42 percent, overtaking those to companies for the first time since September 2016. By mid-2023, they continued to predominate, accounting for 54 percent of all new loans.

↩The Selic rate is the Brazilian federal funds rate. The IPCA is the Extended National Consumer Price Index.

↩g1, “Leader in the world ranking of real interest rates, Brazil has more than double the rate of 2nd place,” Globo, 08/03/2022, https://g1.globo.com/economia/noticia/2022/08/03/lider-em-ranking-mundial-de-juros-reais-brasil-tem-mais-do-dobro-da-taxa-do-2o-colocado.ghtml

↩For analyses that elaborate this argument, see: Luiz Carlos Bresser-Pereira, “Rentier-Financier Capitalism,” Estudos Avançados 32, no. 92 (2018); Luiz Carlos Bresser-Pereira, Luiz Fernando de Paula, and Miguel Bruno, “Financialization, Coalition of Interests and Interest Rate in Brazil.” Revue de la Régulation. Capitalisme, Institutions, Pouvoirs 27 (2020); and Bruno Mader, 2023: 893-913.

↩It is worth remembering that 4.6 percent of GDP was allocated to this exceptional “war budget,” which surpassed the constitutional spending ceiling, and that R$524 billion was actually spent to deal with the health and economic crisis, of which R$322 billion was spent directly on emergency aid. For more, see: Bahia Ligia, Jamil Chade, Claudio S. Dedecca, José Maurício Domingues, Guilherme Leite Gonçalves, Monica Herz, Lena Lavinas, Carlos Ocké-Reis, Maria Elena Rodriguez Ortiz, and Fabiano Santos, “The Brazilian Coronavirus Tragedy,” Insight-Inteligência 93 (2021): 60-89.

↩The Student Financing Fund, managed by the Ministry of Education, provides credit for students who, unable to get into free public universities, seek higher education at private institutions. In 2022, almost 77 percent of Brazilian university students were enrolled in private, fee-paying institutions: Semespe Institute, Map of Higher Education, 12th edition (São Paulo: Semespe, 2022)

↩This restriction in the eligibility criteria left out more than a million defaulting students (40 percent of those in debt with FIES).

↩Lena Lavinas, Lucas Bressan, and Pedro Rubin, 2022.

↩These extensions (for 60 days) and debt renegotiations were authorized for the five largest Brazilian banks by the National Monetary Council, which includes the Ministers of Economy and Planning and the President of the Central Bank. Credit card and overdraft debts were not included in this package. There were parallel measures to suspend and extend collections by the Federal Revenue Service and, at the state level, the payment of electricity and water bills: Wellton Máximo, “Confira pagamentos e tributos adiados ou suspensos durante pandemia,” Agência Brasil (2022), https://agenciabrasil.ebc.com.br/economia/noticia/2020-04/confira-pagamentos-e-tributos-adiados-ou-suspensos-durante-pandemia

↩It is estimated that 66 percent of families who sought new loans in November 2020 were receiving Emergency Aid benefits.

↩The Minha Casa, Minha Vida (My House, My Life) Program (MCMV) was created in 2009, during the second term of President Luís Inácio Lula da Silva, with the aim of expanding large-scale access to home ownership for the low-income population.

↩Idiana Tomazelli, “Pausa na prestação do Minha Casa Minha Vida não alcança faixas menores,” Estadão, 2020.

↩It should be remembered that the principle of fiduciary alienation, which leads to the forfeiture of the property after three months of default, does not apply to track 1 of the MCMV, but to tracks 2 and 3. Data on defaults of more than 360 days comes from the Ministry of Regional Development, https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/mercado/2023/03/inadimplencia-na-faixa-1-do-minha-casa-minha-vida-bate-recorde-e-atinge-45-dos-contratos.shtml.

↩For the authors, as opposed to accumulation debts, which allow the accumulation of assets and wealth: Solène Morvant-Roux, Max-Amaury Bertoli, Sélim Clerc, Malcolm Rees, and Hadrien Saiag, “Surplus versus accumulation measures: the financing of social inequalities in Switzerland,” (Revue Française de Socio-Economie 30, 2023: 219-244).

↩On the occasion of the launch of the program, Minister of Finance Fernando Haddad cited the figure of 70 million Brazilians, an estimate that combined different patterns of delayed payment, not all of which are associated with defaults. Later, the program was designed to serve 32 million.

↩Agência o Globo, “Haddad on Desenrola: ‘We released R$50 billion for banks to carry out negotiations’,” 2023, https://exame.com/economia/haddad-sobre-desenrola-liberamos-r-50-bilhoes-para-que-bancos-facam-as-negociacoes/

↩Agência gov, “Conheça os canais de atendimento do Desenrola do Fies,” 2023, https://agenciagov.ebc.com.br/noticias/202311/conheca-os-canais-de-atendimento-do-desenrola-do-fies-1

↩In 2023, 1.2 million students financed by FIES were in default—a debt amounting to R$ 54 billion (US$ 10.8 billion).

↩In Brazil, there is a Constitutional minimum for health and education. The spending floor for healthcare establishes that 15 percent of net current revenue must be allocated to the national health system, SUS, Sistema Único de Saúde. For education, it is 18 percent. To meet these constitutional requirements would be in disagreement with the new fiscal framework, hence the notion that other social expenses will be sacrificed. It is no coincidence, then, that both the Treasury and the Ministry of Finance have indicated the possibility of amending these constitutional floors—which would worsen the defunding of the nation’s public health and education systems.

↩Bastos PPZ. “Four ceilings and a funeral: the New Fiscal Framework/Rule and Minister Haddad’s Social-Liberal Project,” CECON Note 21, São Paulo, April 2023.

↩

Filed Under