In South Africa’s watershed election last May, the African National Congress (ANC) failed to secure an outright majority for the first time in the country’s democratic history, sinking 17 percentage points from five years prior to obtain just 40.18 percent of the vote. Opponents of the ruling party celebrated the sudden shift in popular sentiment. The ANC’s “liberation dividend”—the condition-free support it has been granted in appreciation for its role in delivering democracy—appeared to have expired. The ANC was becoming an ordinary party, in an ordinary country.

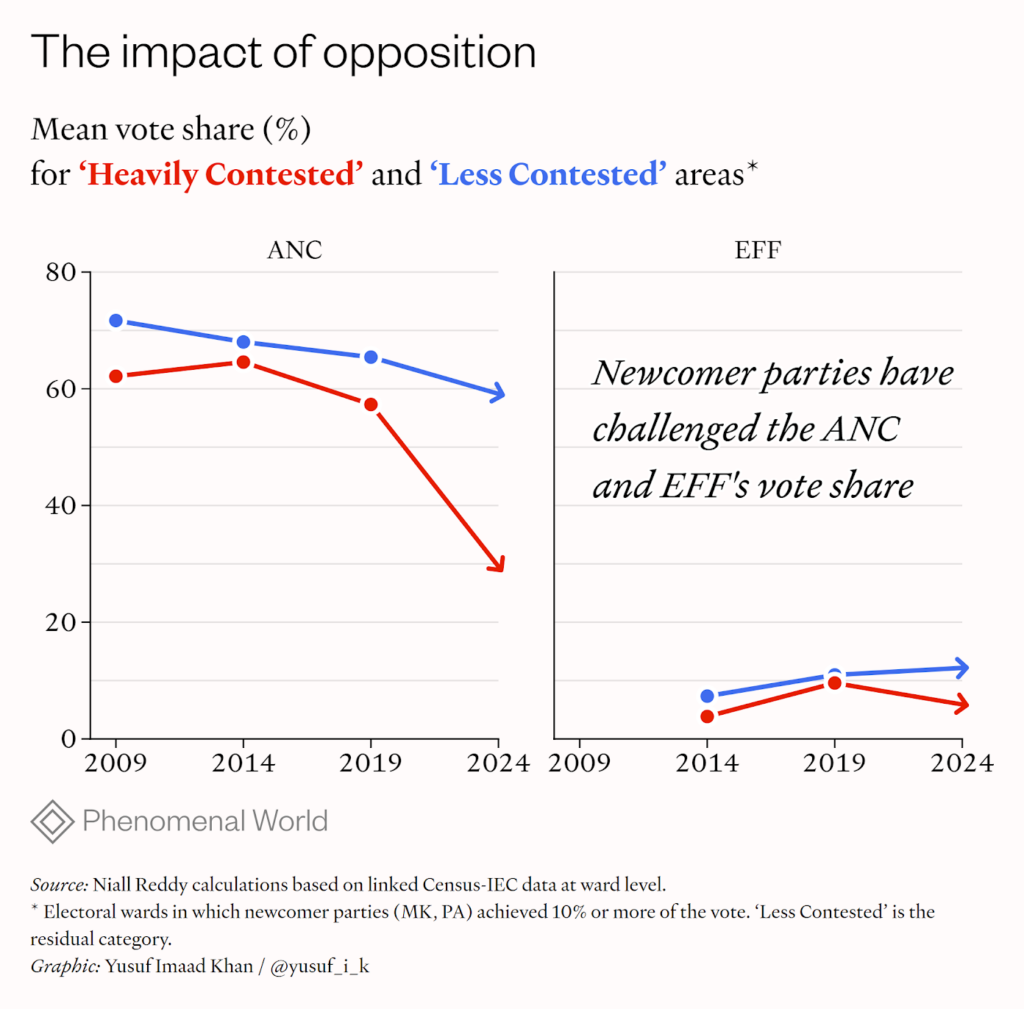

The sudden decline in the ANC’s electoral fortunes can’t be understood without examining the broader electoral dynamics in South Africa, key among them the emergence of the breakaway uMkhonto weSizwe (MK) party, formed by former ANC president Jacob Zuma just six months before the election. MK won 14.58 percent of the total vote, mostly from Zuma’s native KwaZulu Natal (KZN) province. Another relative newcomer, the Patriotic Alliance (PA), cut heavily into the ANC’s vote share in majority colored districts, mostly in the Western and Northern Cape provinces. In voting districts where the ANC was not harassed by newcomer parties, its average vote share dropped by 6.3 percentage points—a more significant drop than the last election, but no earthquake. The party still won a comfortable majority in these districts. In contrast, in areas where newcomer parties made a strong showing, ANC support plummeted, from 57.3 to 29.5 percent.

These figures suggest something simple but important: there has been a supply side issue at the heart of South African electoral politics. The glacial trends in voting behavior that we’ve seen over the past decade are not solely explained by the sheer depth of loyalty to the ANC. Rather, they have much to do with the persisting lack of credible opposition. For specific segments of the electorate, this dynamic changed in May. Where newcomer parties gained traction, the slow trickle away from the ANC turned quickly into a flood. But most voters remained uninspired—only 58 percent of those registered went to the polls—down from 66 percent in 2019—which is less than 40 percent of the voting eligible population. Reversals for the ANC and patchy gains for its opponents are producing a fragmentation of the electoral field which looks set to hold for some time.

Disorienting dominance

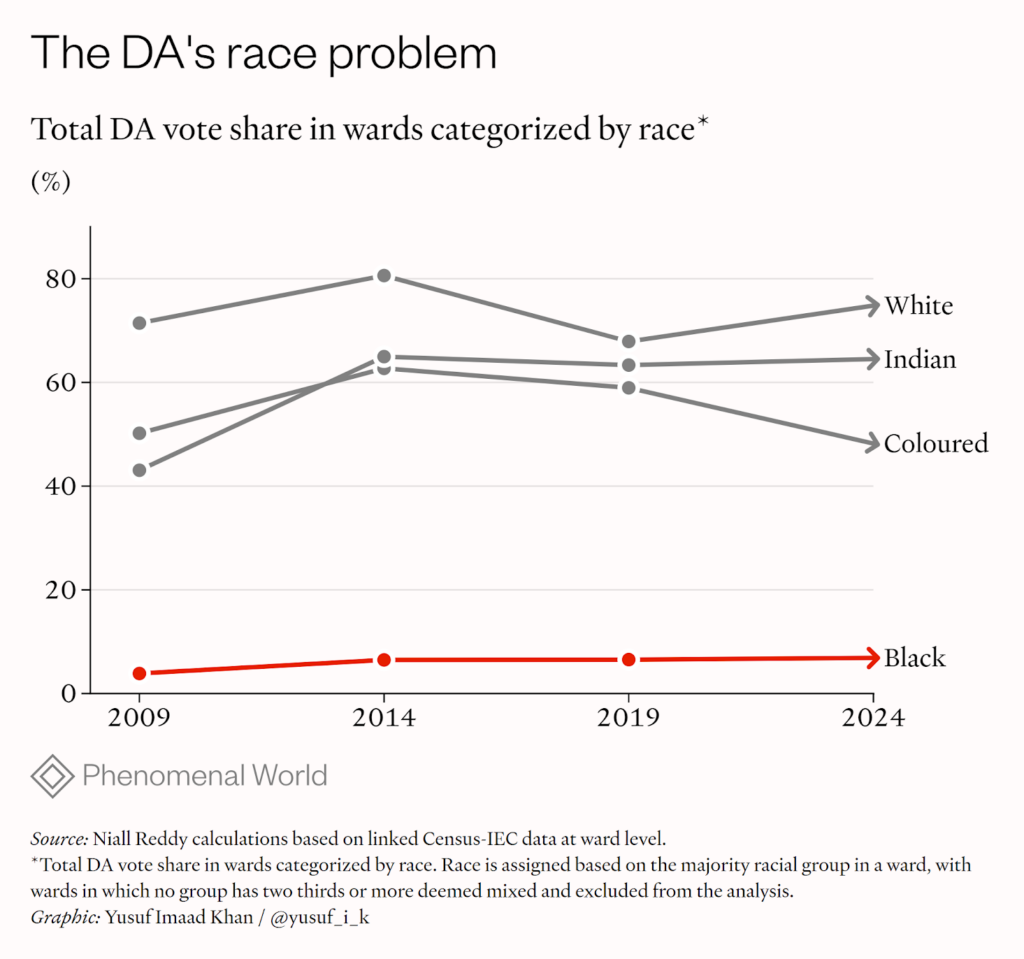

Opposition weakness is partly endogenous to the strength of the ANC: opposition parties have been so ineffective because the ANC has been so powerful. The ANC’s stranglehold over the electorate since the end of Apartheid worked to constrain the space available to its opponents, nudging them towards niche strategies, focused on mobilizing specific segments of the electorate rather than constructing platforms with wide appeal. This is most evident in the case of the Democratic Alliance (DA), which grew out of the Democratic Party—the main liberal opposition in the Old South African parliament. Maligned as race traitors by the ruling National Party (NP), the DP received modest support right up until the country’s first democratic elections, in which it won just 1.73 percent of the vote. But it maneuvered skillfully in the early transition period, hoovering up former NP voters as that party collapsed under the weight of its historical associations with Apartheid and its modern links with the ANC (with whom it had formed a Government of National Unity). The DA also made large inroads into colored and Indian communities around this time, positioning itself as a defender of minority interests in the face of the ANC’s increasingly black-centered notion of transformation.

Propelled by its rapid ascent but facing the exhaustion of its minority-centered growth path, the DA switched to a different strategy from the mid-2000s. In an attempt to broaden its appeal among black voters, it softened its opposition to affirmative action, blended welfarist positions into its economic platform, and began aggressively courting black leaders. Mmusi Maimane’s ascent to the helm in 2014 represented the apogee of this strategy, showing real dividends in 2016 with the party achieving its high water mark of 26.9 percent in local elections. But a decline set in thereafter, as white voters defected to the right and middle ground black voters went back to the ANC following Zuma’s ouster. The DA won only 20.77 percent in the 2019 national elections. With dizzying suddenness, the party’s long gestating pivot to the center left was unwound. High profile black leaders were forced from the seats with most choosing to leave the party, including Maimane himself. A virulently neoliberal, color-blind faction under John Steenhuisen gained ascendancy.

Several factors contributed to this outcome, first of all genuine concern that the DA was losing its grip on its core constituency—white voters. Secondly, the fact that certain key figures had had a sudden rethink on race issues as they were sucked into the vortex of culture war politics spinning out of the US. Thirdly and perhaps most importantly was the internal pushback emanating from white functionaries of the party who saw power slipping from their hands as younger black leaders were rapidly elevated up the ranks.

But the force of the right-wing backlash would have been seriously blunted if the Maimane program had gained real ground. Had he managed to make and sustain large inroads into the black electorate he might have succeeded in shifting the racial complexion of the party, stabilizing his hold on power and drawing in a wider coalition of less ideological actors, particularly in business, who had an interest in fostering a viable alternative to the ANC. As it were, the unpromising electoral math made it far easier for revanchist elements to make the case for the DA embracing its role as a professionalized—and ideologically pure—opposition.

It’s harder to say what strategic bearing the single-party landscape has had on the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), because that party—and the leader-for-life with which it’s inseparably bound—have always been more ideological in nature. The EFF was formed in 2013 by Julius Malema several years after his expulsion from the ANC. A former leader of the ANC’s Youth League, Malema tried to cast his new party in the historical mold of that organization, which was traditionally seen as the radical conscience of the Congress movement. Always heavily disposed towards revolutionary bombast, it’s not entirely clear whether the EFF would have tried to cut a more electable image in its early days, even if a more open path were available. That said, Malema’s track record is hardly one of unshakable principle. Tailed by corruption scandals and deeply mistrusted by centrist voters, his current political brand appears to be hitting up against its limits. The EFF’s selectoral share has been broadly flat for eight years—although this conceals massive churn among individual supporters, which suggests that many treat the party as a protest vote rather than a viable alternative. Moreover, the niche it has chosen to occupy has grown suddenly more crowded with the emergence of MK—most of the EFF’s losses in the last election were in KZN (see the first figure, second panel). While it’s hard to see the party making any wholesale pitch for the middle ground, we might start to see electoral expediency start to curb aspects of its radicalism.

Immigration will be the bellwether here. Outwardly, Malema himself has been fairly steadfast in his commitment to an inclusive Pan-Africanism, a stance which has become increasingly costly as xenophobic attitudes have hardened in the public. In truth, though, the party has always talked left and walked somewhat right on the issue, loudly defending immigrants from the podium while allowing local branches to dabble in xenophobic politics. An alignment of rhetoric with practice might signal a bigger shift in strategic direction.

The ANC’s unassailable dominance hasn’t only worked to disorient existing contenders, but also potential ones. The strategic confusion induced by the ANC’s control over civil society is central to explaining why several decades of vibrant activism at a street and community level have failed to congeal into any political alternative. Radicals outside the ANC have faced an enduring dilemma: deep cultures of protest have provided ample resources for mobilization but resilient loyalties to the Congress tradition have frustrated efforts to cohere organization. This has fomented a deep rooted movementist tendency within the so-called “independent left” which has tended to spurn electoral and party politics in favor of an abiding faith in spontaneous action. The fact is that in over two decades, the only new major opposition parties have come from within the ANC.

Complex cleavages

Strategic errors can’t wholly account for the weakness of opposition. Contenders to the ANC have been forced to navigate a complex political terrain that offers no easy formulas for assembling majoritarian coalitions. The South African polity is partitioned by deep, cross cutting cleavages which have been somewhat obscured by the ANC’s broad church but are now coming into view as the latter recedes.

Race has been of singular importance for most of the democratic period—political scientists tended to refer to South African elections as a “racial census,” with black voters lining up almost universally behind the ANC. Race remains one of the most powerful predictors of individual voting behavior today. DA supporters like to argue that the party is post-racial, pointing out that it is the most diverse major party, which it is in a narrow statistical sense. Somewhere around one third of its regular voters are black, which might have been regarded as an achievement if it weren’t for the fact that 81.4 percent of the country is black. The DA is a major established organization with national reach and profile, a record of (relatively clean) governance and huge resources drawn from its ties to the business community and the white elite. Despite this, it captures less than 7 percent of the vote share in black electoral districts—a figure which has been flat for ten years—hardly evidence that the party is managing to transcend the color line.

South Africa’s sixth largest party after the May elections—the Patriotic Alliance—is a racially exclusivist one. Formed in 2013 by Gayton McKenzie, a former bank robber turned motivational speaker, the party only got 6,660 votes in 2019. In the five years since, it rode a wave of nationalist sentiment in the colored community. It also appealed to conservative voters with hardline anti-immigrant and tough on crime stances.

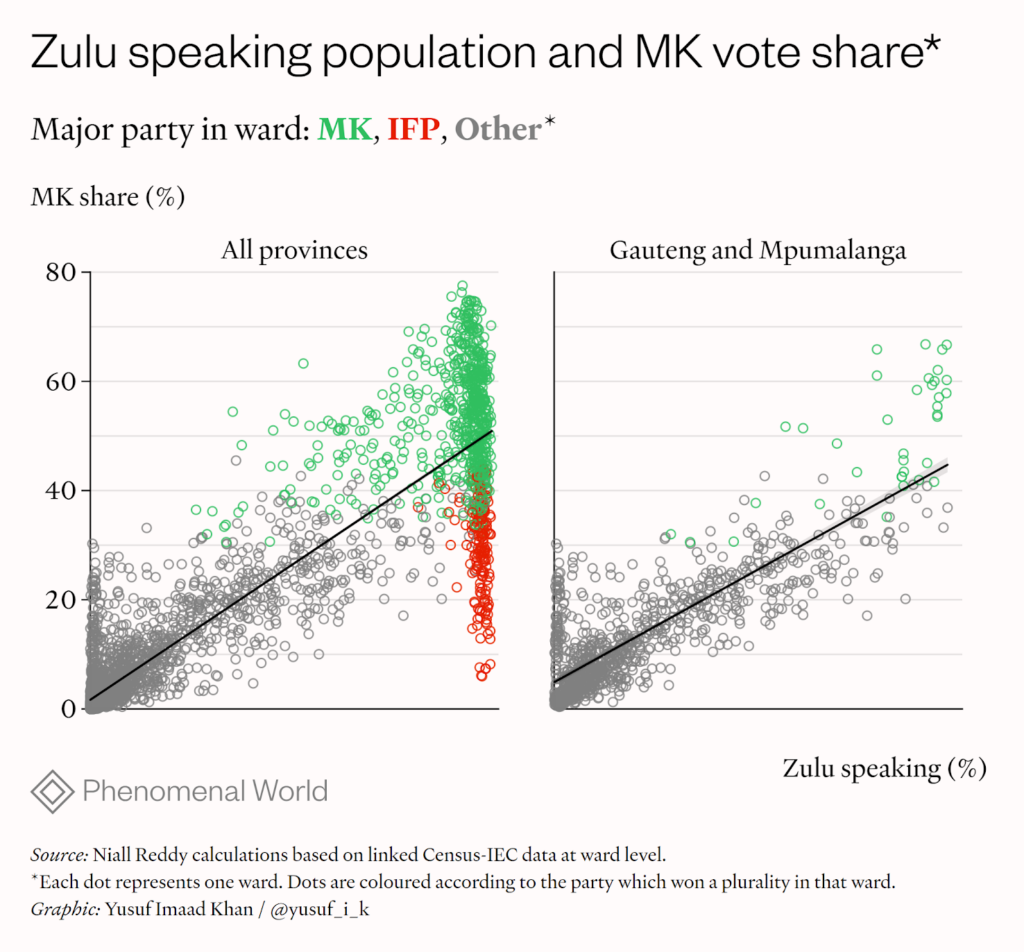

Until 2024, ethnicity had not played a particularly strong part in South Africa’s elections. In the early transition years, large shares of the electorate in the Zulu-dominant KwaZulu Natal (KZN) province aligned with the traditionalist Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP), but when Zuma came to power they were progressively won over to the ANC. The ANC suffered a wave of defections in KZN after Zuma was deposed in 2017, with many of those leaving going back to the IFP or turning to the EFF. In May, Zuma’s MK collected a huge portion of these votes, winning 45 percent of the vote despite having formed just six months prior. The party stoked entrenched social and economic grievances in a province that has borne the brunt of the social and ecological crises in the country. But it also raised traditionalist demands, including the call for a third house of parliament comprising traditional leaders. MK’s stunning victory in KZN was achieved by turning large sections of the ANC to its banner. Whole branches went over to MK, but often in secret, continuing to draw resources from the ruling party while campaigning for its opponents.

This outcome was only possible because Zuma had continued to command mass appeal and huge influence with local potentates in KZN. His resilient image—despite the leading role he played in the numerous crises afflicting the province—cannot be fathomed apart from his ability to act as a standard bearer for renascent Zulu nationalism. Outside KZN, Zuma is one of the most disliked politicians in the country. Yet his party also won substantial support in Gauteng and Mpulmalanga. Some analysts have read this as evidence of the party’s more universal appeal, but a closer look shows that its gains in those provinces track extremely closely to the size of the Zulu speaking population. In parts of the country where Zulu’s speakers are marginal, the party had little traction.

If there was to be an ethnicization of South African politics, KZN was always going to be its ground zero. For historical reasons, ethnic consciousness and organization are far more elaborated there than in other parts of the country. While there are few signs of this so far, there is nonetheless some risk that the emergence of a strong Zulu faction on the national scene will spur ethnic mobilization elsewhere.

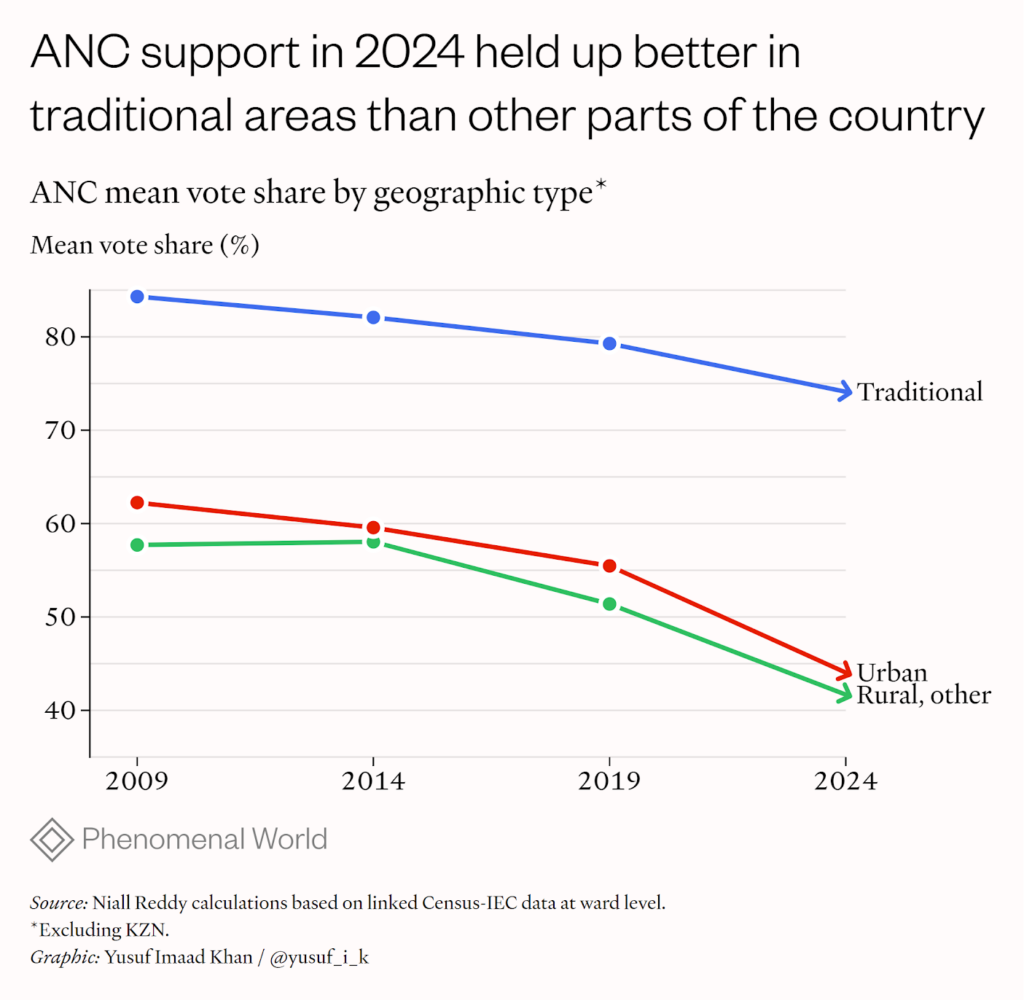

In the countryside, challengers to the ANC face serious dilemmas. The vast majority of the rural population lives under traditional authorities—originally colonial instruments of indirect rule. Today they’re a somewhat mixed bag: some abide by certain principles of consultative democracy while most remain firmly in the colonial mold of concentrated patriarchal authority. For whatever reason, traditional authorities have retained far greater legitimacy than other spheres of government. Because they facilitate access to mining rights and corral their “subjects,” into voting booths, they’ve become important cogs in the ANC’s patronage machinery, helping the ruling party secure its hold over the rural population in exchange for a share of the mineral rents and supportive legislation. Excluding KZN, ANC support in 2024 held up far better in traditional areas than other parts of the country, declining at half the rate it did in urban settings.

Patronage politics

This brings us to the final and most important cleavage in South Africa—the divide created by the vast systems of patronage surrounding the ANC-controlled state. It might seem odd to talk about patronage as a “cleavage,” a term which refers to deep, lasting divisions in the general population. But in fact, this is exactly the nature of the conflict engendered by entrenched practices of rent-seeking that have themselves become a defining feature of post-Apartheid political economy. As Karl von Holdt has argued, rent-seeking in modern South Africa is more than a narrow criminal enterprise, it comprises an “informal political-economic system” that has become the primary vehicle of class formation for an aspirant black elite.

This informal economy is in many ways the progeny of the neoliberal formal economy that the ANC built over the last thirty years. That economy reinscribed the dominance of an increasingly globalized set of major corporations while inflicting enormous damage on the productivity and foreign exchange-generating engines of the economy. While a small but influential cohort of black elites were secured entree into the globalized enclaves of the new economy through Black Economic Empowerment policies, the aspirations of the broader class fraction of emergent black business were thwarted by poor growth prospects and premature deindustrialization. Those aspirations were increasingly displaced from the private economy onto the state.

A similar process occurred at a popular level, as the sclerotic job market failed to absorb the giant surpluses of labor that had been previously contained by the bantustan system. Mass unemployment and state dependency became defining features of the new dispensation. Huge “demand-side” pressures for patronage and rents were thus exerted directly onto the new ANC-controlled state. On the “supply-side,” the conditions for the rapid expansion of the informal economy were laid by the ANC’s politicization of the public service and its attempt to project party control over all levers of government. A “contract state,” defined by bloated procurement expenditures, was brought into being alongside and enmeshed with a “tenderpreneurial” layer of capital. Public employment became a huge engine of social advancement for black South Africans.

Patronage machineries formed the social base of the Zuma presidency. Brought to power in 2007 by a wider coalition in which organized labor was prominent, he quickly jettisoned the left planks of his platform and amplified a traditionalist message more resonant with the rural hinterlands of the party, where clientelism is more entrenched. His administration oversaw a gigantic increase in rent seeking and a surge in public sector employment. But he also ensconced himself personally at the heart of the largest single nexus of corruption in the state, which was centered around the infamous Gupta brothers—a family of Indian businesspeople who had been building close relationships with ANC bigwigs since the 1990s.

The Zuma-Gupta nexus operated according to an expansionist model in which rents were heavily reinvested into accumulating political capital and access. It grew rapidly, with the Gupta’s extending influence over an extraordinary array of public institutions and inserting themselves into the executive level of power, going as far as to summon, appoint, and fire cabinet ministers from their Johannesburg compound. Soon the Gupta machine butted up against the limits imposed by the pockets of still-intact regulatory authority in the state, particularly those located in the National Treasury which had retained broad oversight over procurement and financial intelligence. The “logic” of the informal economy, as von Holdt argues, required the capture of these agencies.

In December 2015, Zuma announced a shock cabinet reshuffle in which a little known backbencher, Des van Rooyen, was announced as the new Minister of Finance. That catalyzed massive opposition from big business, particularly the banking sector, which promised a financial maelstrom should the appointment remain in place. Van Rooyen was removed three days later and a business-friendly candidate reinstated. That incident put big business on a war footing and opened a phase of assertive mobilization against Zuma. In a public relations campaign orchestrated by the infamous marketing firm Bell Pottinger, the Guptas and their allies began to cast themselves as the protagonists of a vision of “radical economic transformation” (RET)—in practice, state capture and large-scale corruption—which was being stymied by so-called “white monopoly capital.”

Thus the relationship between informal and formal economy quickly evolved from one of symbiosis to one of contradiction. Patronage systems helped to stabilize the initial path of neoliberal reform by undergirding the ANC’s legitimacy, but under Zuma they began to critically undermine conditions for corporate accumulation. The most intense predation during Zuma’s administration was targeted at state owned enterprises (SOEs), including those in logistics and electricity. Recent analyses have shown that it was the collapse of these sectors above all else which produced the “lost decade” of growth that stretched across Zuma’s years in power. In setting its sights on the Treasury, the RET faction threatened the key institutional pillar of the fiscally prudent, neoliberal economy and made certain an all out confrontation with large-scale capital.

The informal-formal economy division is therefore a cleavage within the elite sphere first and foremost. Broadly, although these delimitations are not so neat in practice, it pits historically-white but now actually-mixed big business against a “tenderpreneurial” fraction of capital. But the fault lines it inscribes extend much deeper. Patronage in South Africa has always had a social character. Large constituencies are directly incorporated into the circuits of the informal economy through the politicization of public employment, welfare delivery, and the clientelistic practices of branch level machines.

Beyond this, RET forces have amassed a broader social base by framing their project as an answer to the unresolved national question. Convergent interests within the informal economy and the persistent failure of the formal economy to offer pathways for transformation have given RET coherence and social traction. In this way, von Holdt is right to speak of processes of “class formation” incubating within the patronage system. To some extent, these divisions will correlate with unemployment status, which is the key marker of inclusion in the formal economy. According to some surveys, supporters of populist parties are somewhat more likely to be drawn from the swelling ranks of the unemployed. That also gives these parties a more youthful character.

On the other hand, the impact of actually existing “radical economic transformation” has been a catastrophic erosion of state capacity—this has made RET many enemies. The collapse in basic service provision, driven by the failure of utilities and of local administration, has been ruinous for millions of ordinary South Africans. The economy shrunk consistently in per capita terms during Zuma’s lost decade and unemployment reached staggering highs. Anger with corruption runs white hot in large sections of the population. Outside of KZN, Zuma was unable to shirk the blame for this and left office with an approval rating in the low twenties. Other RET figures, like thee EFF’s Julius Malema, faced similar disdain outside of their devoted support base. As the clean-up candidate, the ANC’s Cyril Ramaphosa assumed office with an approval rating in the high 70s.

Age of framentation

The era of ANC dominance is ending. But the historical weakness of opposition, the complex cleavage structure of the electorate, and a low-barrier proportional representation system means that the ANC is not giving way to any single new party but to a fragmented political field. May 29 produced a parcelized legislature: the ANC took 159 seats; three mid-sized opposition parties collectively won 184 seats; two smaller opposition groups claimed twenty-six seats between them, and the remaining thirty-one seats were split between minnows. This is going to cause serious challenges of governance in a society that is deeply divided, with no history of coalition politics at the national or provincial level. Recent turbulence in the local government sphere, where coalitions have been a widespread reality for some years now, provides a concerning foretaste of the problems to come.

But fragmentation may be the main reason South Africa hasn’t been dragged along in the global undertow of populist authoritarianism. If Dani Rodrik is right to attribute the populist tide to globalization’s aftershocks, then South Africa should have been among the first countries to have undergone democratic “backsliding.” In the last few decades, the country has experienced major trade and immigration shocks, aggravating an already acute crisis of mass unemployment and high crime. But while populist formations (MK and the EFF) have grown, these so far haven’t shown any potential of achieving the level of majoritarian support that has facilitated democratic erosion elsewhere.

We shouldn’t let this be cause for more South African exceptionalism. It’s true that the liberation legacy imparted a certain resilience to democratic institutions here, not least through a strong constitutionalist strain in the Congress tradition. But it’s also true that popular sentiment has grown more nativist and more authoritarian in recent years, tracking the populist tide globally. A key reason this hasn’t produced the same kind of electoral result is that globalization shocks, rather than producing their own divisions, have been refracted through the post-colonial cleavage structure, which remains dominant. Consequently, local variants of populism cannot be likened to those abroad, they are largely sui generis. The EFF and MK, the two major populist parties, emerged from within the ruling party. They are not outsider movements, and their moral grammar is one of transformation not anti-corruption. Their vital energies derive from elite patrimonialism rather than middle-class chauvinism.

Crucially, their class configurations are very different from other populists in the global South, most saliently in that they are locked into a deep antagonism with large scale capital. This gives them a much more difficult road to power, but it also makes them more dangerous. Their irreconcilable breach with the investor class means that they have no means of crafting a viable economic program. That in turn means that, to govern, they will either have to moderate drastically and enter a wider coalition—or they will have to usurp the investment prerogative from their antagonists. The latter route implies a direct conflict with property and with democracy, not a slow curtailment of political freedom as has been the modus operandi of most modern authoritarians.

Lumping the EFF and MK together might be seen as analytically questionable when they are so divergent ideologically. The EFF describes itself as Fanonian-Marxist and draws heavily on the caché of the Left (minus the democratic bits) in its manifestos, which denounce exploitation, call for state-led development and espouse Pan-Africanism. MK also calls itself a left party, though makes no similar effort to live up to the label. Its message is brazenly chauvinistic, misogynistic and even feudalist. Yet the two find themselves in an ever tightening alliance, now made official in the parliamentary “Progressive Caucus” which also comprises a number of smaller nationalist and ostensibly left parties. Key figures associated with Zuma’s project, like the disgraced former public protector Busisiwe Mkhwebane, have joined the EFF’s parliamentary benches. The convergence of EFF and MK demonstrates most clearly the ways in which the informal-formal divide has become the primary contradiction in the South African social formation—if not by way of its popular salience then by way of its centrality in organized political conflict. It’s a common commitment to graft, rationalized as historic redress, that binds these parties together.

While organizationally fragmented, the political field is more and more splitting into two great hostile camps: the liberal camp on the one side, and the kleptocratic on the other. What complicates this otherwise neat bifurcation is the ANC, which straddles both liberalism and kleptocracy. Its ruling faction under Ramaphosa sits firmly in the liberal camp and has strong ties to the corporate bourgeoisie. There is no openly organized RET faction in the ANC though key power brokers, including the chairman and deputy president, retain ties to the kleptocratic camp. They are said to have preferred an alliance with the EFF following May’s result. The Gauteng branch of the ANC, in which the deputy president has his base, has rebuffed the national organization’s mandate to seek co-governance with the DA.

More broadly, the party as a whole remains utterly enmeshed in the circuits of the informal economy. This doesn’t necessarily mean that a majority favors a return to the Zuma model of statecraft. There is likely a substantial “moderate” faction that wants to keep up the flow of rents but to mitigate their antagonism with the formal economy and avoid the electoral consequences of regression to state capture. At a grassroots level and within the Left of the party, Ramaphosa’s clean up agenda likely remains popular. His appeal with the electorate, which despite some knocks remains much higher than that of the ANC itself, is still his greatest advantage within these factional conflicts.

Future fractures

Hence the ANC was deeply divided over the coalition question following May 29’s outcome. There were loud voices denouncing a potential agreement with the DA as amounting to doing a deal with Apartheid. Others preached doom should the ANC bring RET back into the fold. Ramaphosa, the consummate negotiator, deftly navigated these choppy waters, managing to secure his first order preference in a consolidation of the liberal camp; the so-called Government of National Unity is in practice a deal between the ANC, the DA, and the IFP. None of the other minnows in the tent have the seats to make any difference. If the Government of National Unity is in many ways an achievement, it’s been won by Ramaphosa without expending the considerable capital that would have been required to have called openly for a DA pact. Instead, Ramaphosa flung the door wide open, inviting all parties to join the GNU while betting correctly that RET’s intransigence towards working with “white interests” would prevent the EFF and MK from joining an alliance. At the same time, by keeping alive the threat of an RET tie-up, he managed to extract a highly favorable deal for the ANC in negotiations with the DA, holding on to the main centers of ministerial power.

Ramaphosa’s masterstroke has given the country a welcome reprieve. Had the ANC chosen to form a government with the kleptocratic camp, it would have thrown fuel on the simmering social crisis and reversed recent gains. But major questions present themselves about how long the GNU coalition will last. Ramaphosa’s term as ANC president will end in 2027. He currently has no successor of the stature that could guarantee the continued stability of his project and the main contender to take over from him, Deputy President Paul Mashatile, is generally thought to have EFF leanings.

To win decisively, the liberals would have to chip away at the material basis of kleptocratic power. They would have to squeeze the informal economy on both the demand and the supply side. That would require firstly an ambitious project of state rebuilding to professionalize the public service and establish centralized control over procurement. Ramaphosa has no possible means of purging corruption root and branch but there may be ways in which he might canalize it such that rents start to align with rather than undermine institutional goals, in the manner that East Asian developmental states seemed to achieve. On this front, there are some faint grounds for hope. Ramaphosa and his GNU partners are pro-reform. Public service transformation might be somewhat easier to sell to the ANC now that it is losing its monopoly over appointment. History shows that dominant parties are more likely to accede to a de-politicization of the state when confronted with the possibility that the weapons of patronage might be turned against them.

Much dimmer are the prospects for a major revamp of South Africa’s defunct growth model. Here the liberals don’t have any discernible vision or program. The GNU’s immediate priority is to carry forward Operation Vulindlela, Ramaphosa’s marquee reform program, which focuses on modernizing the country’s infrastructure and undoing the damage that state capture did to key network industries. It has made notable progress, most visibly in the dramatic turnaround in the electricity crisis. At the time of writing, South Africa had gone 144 days without scheduled outages. In 2023 there were only seventeen calendar days in which the lights stayed on uninterruptedly.

Modest though it may be, Vulindlela stands a good chance of affecting meaningful improvements given the complete rut in which the economy is currently stuck. That gives the GNU some welcome runway in the medium term. But even in the rosiest scenario in which growth bounces back to around 3 percent, is it not clear that this will be enough to consolidate the liberal bloc in the longer run. The country’s current unemployment rate is an eye watering 41.9 percent. The vast majority of those caught in the trap of long term exclusion from the job market are young people. Unless the political class sets its sights higher, towards a fundamental transformation of South Africa’s economic model, the country will continue to skirt around the chasm of populism and social unraveling.

Filed Under