In the eyes of the IMF, a G20 panel, and, lately, the US Treasury Secretary, the time has come for multilateral development banks to adapt their development mandates to the logic of derisking. This tactic—lauded as a solution for “mobilizing” the trillions necessary to achieve the green transition—demands that public entities shift private investors’ risks onto their own balance sheets, incentivizing investment to meet the world’s infrastructure needs.

Although development banks have floated serious plans to reorient themselves toward catalyzing private investment since the “billions to trillions” hype in 2016, such efforts never took off. The World Bank’s recently leaked “Evolution Roadmap” is its latest attempt to kickstart derisking at a global scale.

But the roadmap’s emphasis on mobilizing private finance through derisking obscures one proposal that on the surface appears to run the other direction. Securitization allows public entities and development banks to offload their assets to the private sector, thereby transferring risk away from themselves and freeing up their balance sheets for more immediate lending. To be sure, securitization still fits snugly within economist Daniela Gabor’s Wall Street Consensus, in which governments meet development goals by turning public services into investment opportunities for private finance.1 But while derisking calls for the public sector to shoulder additional risks, securitization calls for shrugging them off.

How would securitizing the World Bank’s portfolio work, and how does this tactic relate to the larger derisking turn in development finance? Is securitization a preferred alternative to derisking, or does it align with its broader logic?

Parts of the development community have advocated for risk transfer through securitization as both countercyclical and prudent: securitization supposedly frees up multilateral development banks’ balance sheets for more green investment, especially during times of market stress and higher emerging market borrowing costs. The best available precedent is the African Development Bank’s (AfDB) 2018 Room2Run initiative, through which it securitized $1 billion of its private sector project loans.

On closer examination, however, securitization’s promise to free up public balance sheets parallels the promise of privatization—and it threatens to produce the same failures. The securitization of development bank assets is procyclical insofar as it chains development finance to volatile private investment trends, and as such it may ultimately reduce development banks’ fiscal space for investment. While securitization may free up balance sheets in the short term, in the long run this is yet another financial “innovation” that will put private investors in the drivers’ seat of the green transition―likely at considerable cost to everyone else.

Securitization or privatization?

Conventional asset-backed securitization for green infrastructure resembles mortgage-backed securitization. The World Bank or any other entity could pool and collateralize its assets’ revenue streams to borrow on cheaper terms from an institutional investor.2 Given the existing framework for securities regulation and risk weighting, proponents of development bank asset securitization believe that “capital relief” or “increased lending headroom” will result, given that securities they offer up will be cheaper and less risky for investors to purchase. The amount of risk that a development bank can offload will determine how much more investment it can undertake—a mundane argument, consistent with the laws of accounting.

This line of reasoning, however, echoes the World Bank’s Washington Consensus promise that freeing up public balance sheets through the privatization of state assets would improve a country’s investment climate. Securitization and privatization both press public entities to surrender control over assets, or at least their revenue streams.

Privatization, for its part, has not exactly succeeded. Water privatization drives in Bolivia, Nigeria, and elsewhere across the global South have been failures. The complete privatization of British utilities is complicit in the country’s cost-of-living crisis. And the privatization of Puerto Rico’s energy grid has not helped the territory’s communities weather increasingly severe climate disasters. Writing off these letdowns as examples of poor implementation only serves to paper over privatization’s glaring conceptual flaws.

Crucially, investors don’t want to buy just anything. Given a pool of public assets to choose from―hospitals, utilities, transit―private investors will cherrypick those with steady revenue streams from wealthier and more concentrated groups of citizens. Absent strict regulation, infrastructure privatization usually also permits an asset’s new owners to raise prices, lay off staff, and diminish service quality―all to maximize revenues and cut costs. Asset manager Macquarie’s ownership of an English water utility, for example, left customers paying higher prices while letting raw sewage leak into the country’s rivers, while the proposed deregulation of India’s electricity distribution sector has sparked protests over fears that it will degrade rural electricity provision and harm electricity sector workers. While the private sector profits from serving the privileged, the public sector loses money serving everyone else. This segregation is by design.

While securitization could leave a development bank’s assets under nominally public control, it ultimately mirrors privatization. If development banks must depend on the sale of their securitized assets for new financing but investors will buy only those that offer the least risk, then banks face a perverse incentive to offload their best assets. Private investors’ sustained retreat from higher-risk global South economies suggests that any successful securitization will be quite limited in both scale and revenue generated.

Regardless, public-serving infrastructure remains an illiquid asset with unpredictable future revenues. A rush to offload these assets will quickly depress their sale prices, subsidizing private buyers and leaving governments and development banks short of the capital relief they’re seeking.

Liabilities

Even if development banks are compensated fairly for their assets, Australia’s “asset recycling” program demonstrates how they could end up saddled with greater liabilities than they started with.

Asset recycling was an infrastructure privatization program established in 2014 with the same explicit goal as infrastructure securitization—to free up “asset rich, cash poor” public balance sheets for new investment. By the time it was shut down in 2016, however, it seems to have done the opposite. Selling future revenue flows to pare down existing liabilities should have left Australian states’ net debts—and therefore their ability to raise new investment—unchanged at best. In reality, because “income-generating assets were sold to finance new investments that did not generate income,” in the words of Australian economist John Quiggin, asset recycling increased Australian states’ debts and decreased public sector net worth in the eyes of private creditors.

Because many of the new investments were public-private partnerships, Quiggin judged that financing them usually involves “hidden government borrowing or guarantees.” Indeed, Australia’s federal government privatized its Federal Health Commission to promise a two-year, 15 percent subsidy to every new infrastructure project built with money from a state asset sale.3

Green infrastructure securitization could see similar results. Many of the investments most needed to combat climate change―dense housing, mass transit, mangrove restoration―are public goods that don’t easily generate the kind of income that attracts private investors. That goes especially for emerging markets, where regulatory and currency risks can spook foreign capital. Following Quiggin’s logic, persistent asset securitization may therefore erode development banks’ balance sheets over the long term—returns-generating assets will be collateralized to finance necessary but likely unprofitable green infrastructure and restoration projects. The subsequent deterioration in these banks’ net worth won’t look good to shareholder governments and might impact their willingness to recapitalize. Development banks will be incentivized to build infrastructure that can turn a profit. This course of action would not only be massively inequitable, it would fail to meet the world’s green investment needs.

Room2Run

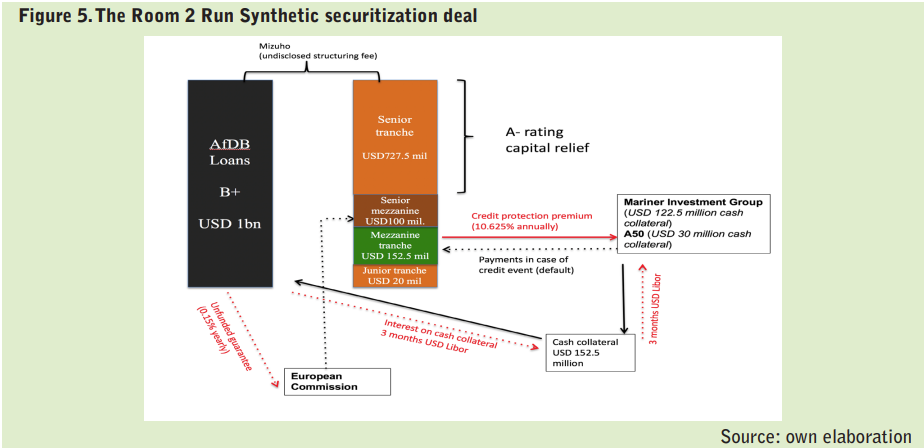

The AfDB’s Room2Run initiative serves as a test case for the future of securitization as a development strategy. Here, $1 billion of private sector loans were “synthetically” securitized. Projects themselves stayed on AfDB’s books; all AfDB did was transfer the risks of its securitized loan portfolio to private investors, allowing it to mobilize $650 million in new lending, according to the bank. Synthetic securitization achieves a similar outcome to conventional asset-backed securitization through the purchase of credit protection, which could allow the World Bank to lend more elsewhere.

Room2Run highlights how securitization puts public money towards derisking private finance rather than the other way around, precisely by shielding the private sector from the highest risk assets. The AfDB held onto the lowest tranche of its security to insulate private investors from the risks of the weakest assets in the portfolio and paid a hedge fund for credit protection on the second-weakest tranche, costing around $100 million. Additionally, the AfDB secured a $100 million guarantee from the European Commission over another tranche of Room2Run. In total, Room2Run saw the AfDB retain ownership of nearly $750 million of the $1 billion in loans that it securitized. Although the AfDB was securitizing its private sector portfolio, which should have offered higher returns than its public-sector counterpart, not even these private assets were “bankable” without the AfDB’s or European Commission’s derisking measures.

Freeing up $650 million in new lending (if the figure is accurate) is still significant. An Inter-American Development Bank working paper argues that for securitization to work, banks and governments must address the considerable information and risk appetite asymmetries between themselves and private investors. But given Room2Run’s four year preparation period and perhaps overcomplicated structure―these are bitterly tough coordination problems to solve―attempting to meaningfully scale securitization into a legitimate climate finance solution wastes precious time.

Risk-taking

By relying on the whims of private investors’ risk appetites, development banks are tying themselves to global financial cycles that could render their climate investment goals unachievable, while also exposing them to even greater investment risks.

Privatization schemes falter when global financial conditions do. Emerging market governments struggle to secure a fair price for their assets when investors won’t spend on risky ventures abroad.4 Similarly, governments and development banks that securitize their infrastructure assets in emerging markets must ensure that the risk-adjusted returns match or exceed those of dollar-denominated assets to keep investors interested.5 Under today’s stormy global market conditions, “investors must be given a reason (higher returns) to invest in an EM rather than move their money into less-risky US assets,” a recent World Bank blog summarizes. This sheer scale of derisking required to placate private investors―which will rise as risk perceptions worsen―will undoubtedly harm the health of public balance sheets.

What’s more, financial policymakers have long known that securitization is correlated with overall markets in a potentially damaging way. “Securities financing markets fed boom-bust cycles of liquidity and leverage,” former Bank of England governor Mark Carney wrote in 2014 about the shadow banking industry that caused the 2008 global financial crisis. Similarly, as Gabor noted in 2018, “the IMF recognizes that encouraging countries to join the global supply of securities exposes them to the rhythms of the global financial cycle over which they have little control.”

What happens when the revenue streams backing these securities become erratic or dry up? In a world of intensifying, interlocking, and sometimes unforeseen challenges, there is an increasing chance that the infrastructure assets development banks and governments turn into collateral become illiquid or insolvent. A collapse in collateral value that threatens high-leverage institutional investors involved in a securitization scheme would stop any infrastructure securitization market in its tracks.

And yet today, Carney chairs the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero, a group of institutional investors and financial institutions allegedly committed to a swift green transition, which has praised securitization as an innovative financial structure. The IMF’s latest Global Financial Stability Report also endorses securitizing green bonds ”with the public sector providing risk reduction.” The proponents of securitization have failed to acknowledge the dangerous interplay between financial and climate risks.

Boom or bust?

Development banks are part and parcel of the climate crisis and policy responses to it. But those that retool themselves to mobilize private capital will end up funding infrastructure that meets private standards for investment, not public ones. Despite their seemingly opposite motives, both derisking and securitization work in tandem to guarantee private investors consistent returns backed by public funds.

As the parallels between privatization and securitization make clear, turning public investments into worthy collateral for private investors embeds development banks into a crisis-prone, undemocratic financial system. As Anusar Farooqui and Tim Sahay put it, “a boom-bust dynamic” in green investment “would destroy the moral economy of the energy transition,” not to mention waste valuable time that the environments we want to preserve do not have.

Reincarnated in its Evolution Roadmap, the World Bank’s push to “maximize finance for development” has ended up promoting the wholesale financialization of development itself. By letting privately held notions of risk, profit, and thrift guide the provision of global public goods, development policymakers are surrendering public control over the future of the planet. Relying on private capital to make ends meet is a Faustian bargain, threatening to transform governments and development banks into the risk-averse, profit-maximizing investors whose money they’re seeking.

Disclaimer: the views expressed here are the author’s personal opinions alone. They do not necessarily represent and should not be construed to represent the views of the Department of Treasury or the United States Government.

FootnotesGabor explored the intricacies of securitization in detail in 2018. Her research is crucial both to this piece and to development finance more broadly.

How much cheaper should depend on how much revenue the fund thinks the collateral can generate (more precisely, the net present value of the revenue stream adjusted for perceived payment and regulatory risks). That being said, securitization is more than simply collateralizing different revenue streams; it requires an originator to legally reorganize a financial asset with one revenue stream and risk weight into an asset with senior and junior revenue streams, each with a different expected return and associated risk weight. This financial engineering should make it cheaper for financial institutions to invest in these assets: regulators should permit these institutions to hold fewer reserves against these assets because these senior claims are less risky than a claim on the whole asset.

Governments may also need to keep funds on hand to cover the consequences of privatization: the New South Wales state government had to subsidize consumers’ energy bills after “electricity prices doubled in five years after poles and wires were privatized.”

The IMF’s latest Global Financial Stability Report judges EM equity and bond assets as far less liquid—and therefore far more vulnerable to financial system shocks—than their advanced-economy counterparts.

The price of a US Treasury bond, the world’s safest asset, sets the cost of dollar-financed investment worldwide―and, when it rises, investment sputters worldwide as capital flees emerging markets toward dollar-denominated assets.

Filed Under