China has ended zero-Covid. The resultant viral tsunami is crashing through China’s cities and countryside, causing hundreds of millions of infections and untold numbers of deaths. The reversal followed widespread protests against lockdown measures. But the protests were not the only cause—the country’s sagging economy also required attention. Outside of a few strong sectors, including EVs and renewable energy technologies, China’s economic dynamo was beginning to stutter in ways it had not in decades.

Whenever global demand or internal growth faltered in the recent past, China’s government would unleash pro-investment stimulus with impressive results. Vast expanses of highways, shiny airports, an enviable high-speed rail network, and especially apartments. In 2016, one estimate of planned new construction in Chinese cities could have housed 3.4 billion people. Those plans have been reined in, but what has been completed is still prodigious. Hundreds of millions of urbanizing Chinese have found shelter, and old buildings have been replaced with upgrades.

The scale of construction has been so prodigious, in fact, that it has far exceeded demand for housing. Tens of millions of apartments sit empty—almost as many homes as the US has constructed this century. Whole complexes of unfinished concrete shells sixteen stories tall surround most cities. Real estate, which constitutes a quarter of China’s GDP, has become a $52 trillion bubble that fundamentally rests on the foundational belief that it is too big to fail. The reality is that it has become too big to sustain, either economically or environmentally.

Recognizing this danger, in 2020 China implemented limits on developers’ ability to borrow. Firms that crossed the three “red lines”—liabilities-to-assets ratio of 70 percent, 1:1 net-debt-to-equity ratio, and cash greater than short-term borrowing—would be cut off from accessing more loans, an attempt to reduce the leverage of developers who had become addicted to debt-fueled growth. Evergrande, a mega developer, became the poster child of unsustainability, defaulting with over $300 billion in debt. Other developers such as Kaisa, Fantasia, and Modern Land also failed to repay creditors in 2020 and 2021.

Many buyers who bought their homes in “pre-sales”—that is, paid for their houses prior to their construction—now find that those funds have been squandered, causing some to boycott mortgage payments on homes that may never be built. Freedom House’s China Dissent Monitor has tracked 272 separate acts of dissent, mostly group demonstrations, related to housing in 2022. Developer defaults had exploded past $31 billion by August of last year, and markets have priced in over $130 billion-worth.1 Most ominously, the belief that real estate is a good investment seems to be dissipating. As economist Michael Pettis noted, three years ago, a People’s Bank of China survey found the ratio of people who thought house prices were likely to rise versus decline to be 2.4 to 1. In the December 2022 PBOC survey, that figure has dropped below parity.2 The news that China’s population shrank last year once again calls into question who, precisely, is ever going to live in all this housing.

Despite knowing that the construction party needs to be wound down, all indications are that the government will again try to pump up the sector. Developers’ stocks have already rocketed upward, and the PBOC sounds a lonely note in trying to tamp down expectations as officials worry about China catching the global inflation that it’s avoided so far.

All of this is symptomatic, however, of a deeper problem facing China’s economy, a complex interaction of finance, land, and real estate that I call the carbon triangle.

The triangle

In the 1970s, Chinese political elites led by Deng Xiaoping emphasized that the country needed to “seek truth from facts”—a classical Chinese maxim popularized by Mao Zedong himself—rather than remain mired in ideological battles while the people starved. This clever quoting of Mao to upend Maoism helped orient politics and policies towards a few key metrics. Now it is GDP, but initially, this meant increased agricultural production.

China is a country of more than 1.4 billion people and has a history of famine; the disaster of the Great Leap Forward killed as many as 40 million people barely sixty years ago. Making sure that there is enough food to eat has been a principal concern of political leaders ever since and was the source of another “red line” policy—the area of cultivated land is not to be diminished. In a 1994 fiscal overhaul, the central government granted cities the power to convert land for urban use, in part as an attempt to corral blind urban development.

As with most systems designed to maximize particular performance indicators, this system of “limited, quantified vision” created blindspots where problems such as corruption, pollution, and falsification were allowed to accumulate. But the principal issue was over-investment in pursuit of GDP growth. Construction directly increases GDP, even if what is being constructed barely gets used. But development-incentivized local cadres faced an additional constraint—the central government alone maintained taxing authority, and finding the revenue to pay for their own salaries, let alone public goods and services, has always been difficult. This land conversion was their solution.

Land sales became a critical budget fixer for heavily indebted Chinese local governments, providing about 30 percent of revenue in 2021. In 2022, however, with the softer real estate market, this income stream plummeted by nearly a third. As a consequence, government deficits are breaking records—8.96 trillion yuan in 2022—just as they face some 3.65 trillion yuan in debt repayments this year. A long discussed property tax continues to face resistance from the propertied middle classes and the officials in their circles. With limitations on where they could build and facing the local land monopolist, developers bid up the prices of land leases at auctions. By then building on that land, they helped local officials both by providing revenue directly and by contributing to GDP.

Why build with 30 million new apartments still empty? There may not be people who want to live in them but there are people who want to buy them. Despite persistent poverty, economic growth has created a class of hundreds of millions of Chinese people with plenty of savings and not a lot of places to invest them. Capital controls limit their ability to diversify their holdings outside of the domestic market, and the Chinese stock market makes gambling in Macau look like a safe bet. But the government has repeatedly signaled that it will not let home prices collapse.

The carbon

Why do I call this the carbon triangle? Because China is the world’s leading emitter of greenhouse gases, producing around 30 percent of global carbon emissions; the US, at No. 2 contributes 13.5 percent.3 Beyond direct emissions, constructing empty buildings is a significant waste of labor and of land. Land is necessary for agriculture as well as for acreage-hungry renewable energy sources like solar and wind. The vast swathes of concrete that constitute Chinese cities are also increasingly vulnerable to massive flooding episodes. Top-down efforts such as the “sponge city” campaign to adapt urban infrastructure for heavy rainfall are unlikely to prove sufficient; many are already falling by the wayside.

China’s emissions are different from those in the US (and even more different than Europe) in shape as well as size. While transportation, electricity, and heat dominate emissions elsewhere, in China, electricity, construction, and industry are king.

China produces more than half the world’s steel and cement, and those two sectors alone account for about 14 percent of global CO2 emissions. Chinese steel and cement production have become more efficient over the past decade, but their emissions have skyrocketed nonetheless because production volumes have increased by so much more—a multiple of three for cement and five for steel compared with fifteen years ago. The extent of this endeavor can be simultaneously difficult to fathom for outsiders and perfectly normal to insiders.4 Consider the following section from David Sandalow and co-authors excellent Guide to Chinese Climate Policy 2022, buried in the middle of paragraph of Chapter 18:

Tsinghua’s Institute of Climate Change and Sustainable Development estimates that the massive demolition and construction of new buildings leads to as much as 40 to 50 Mt of steel and 220 to 260 Mt of cement every year. When taking into account the energy consumed in the construction process, this results in an additional 120 mtce5 energy consumed every year, or 5 percent of global energy consumption (emphasis added).

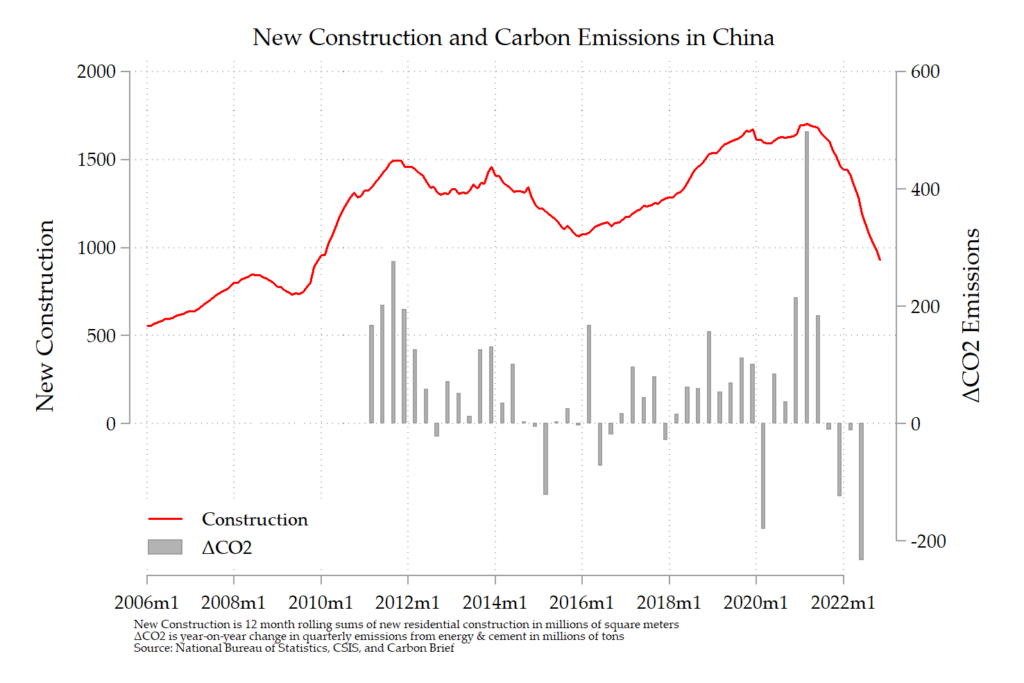

Again much of this construction is not actually producing value as housing or office space. Only fugitive methane emissions and deforestation put more greenhouse gasses into the atmosphere while producing less value than the Chinese construction sector, which means that right-sizing that sector represents an immense opportunity to slash global emissions. To be clear, the ‘value’ here is not meant in monetary terms but instead in terms of services for people, as the IPCC put it, to help us live our lives well. Rhodium Group estimates the stable level of demand for construction in China at 550-750 million square meters annually, which would require another 15-37 percent decline from the level of newly started projects today. The IMF recently suggested a higher level and wider range, 750-1050 million square meters, for the steady-state. However, the upper range here is almost certainly too high. Completed construction has remained bouncing around 800 million square meters for the past decade, so a suggestion that what is needed is an increase of 200 million square meters annually given all of the existing emptiness is odd. That answer though raises another question—why focus on construction starts rather than completions, which aren’t so far off of the steady-state level? Projects that begin construction but stall out tend to use much of the gross tonnage of material involved. See all the steel and concrete husks of projects that have faltered with the more intricate work to transform those husks into livable units. But in emissions terms, those bare husks represent most of the embedded emissions in a constructed building.

If residential construction continued to slide to say 600 million square meters, Chinese cement production could fall from well over two billion tons annually to only 1.2 billion tons going forward. Steel could follow a similar path. A gigaton of CO2, 2 percent of annual global emissions, could disappear.

That right-sizing has begun. The question is, will it be allowed to continue, or will the Chinese government succeed in achieving its 5 percent GDP growth target by repowering its over-leveraged real estate market?

Chinese officials have long understood that the carbon triangle needed to be dismantled, but they have struggled to do so because of how deeply enmeshed it is in the country’s political and economic fortunes. If China is able to rev up the economic engine with real estate—as many Australian mining conglomerates, Chinese housing speculators, and vulture funds scooping up developers’ distressed debt are hoping—then emissions will surge. But while powerful forces are invested in that path at the moment, everyone involved understands that this debt-fueled, deficit-exploding, inequality-stretching, land-wasting concrete expansion cannot and should not continue forever. Demand signals remain weak, yet most economists predict growth at around 5 percent, which would be impossible without a return to growth in real estate construction. Xi Jinping has regularly declared that “houses are for living and not for speculation.” If this idea can move from mere slogan to reality, then China will have taken a major step towards building its own green new deal.

New stats are dropping next week. Most notably GDP will fail to hit the 5.5 percent target threshold.

↩Same survey, from SCMP: “The income confidence index dropped 2.1 percentage points from the third quarter to 44.4 percent, a decade low, suggesting widespread pessimism.”

↩This accounts for international trade. Consumption versus production emissions statistics aren’t that different, even in China.

↩The unlikely pair of Bill Gates and David Harvey share their appreciation for Chinese cement statistics. China produces half of global totals, and the scale is immense, and in the three years from 2009 to 2011, China used more than the US in the entire twentieth century.

↩Million tons of coal equivalent

↩

Filed Under