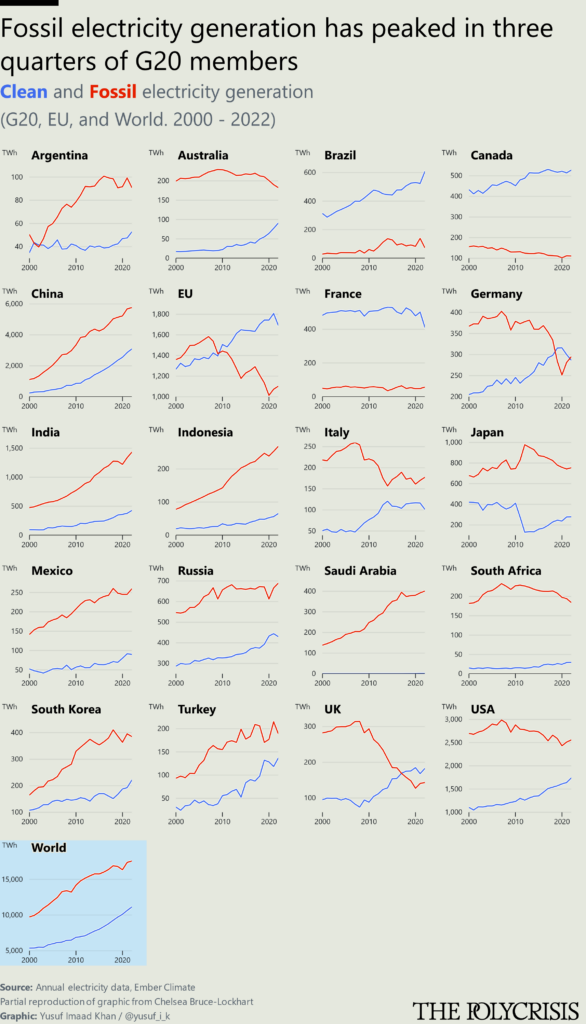

A world with terminally declining oil demand has never been experienced before, but the growth era for fossil fuels is ending, as many producers, investors and forecasters are acknowledging. This does not put climate goals in close reach, as CO2 flows need to fall far more dramatically to reduce the stock that is already too high. But pathways to both energy independence and strategic export industries no longer have to involve fossil fuels. Instead, they center on new manufacturing capabilities and technologies, mineral resources, and increasingly delicate trade relationships and security alliances.

Countries highly dependent on fossil fuel exports are seeking to diversify. Among the wealthiest countries in this category, Norway has been doing this most decisively via its sovereign wealth fund. Meanwhile, Gulf Coordination Council countries are deploying footloose petrodollars via private acquisitions targeting new industries and an increasing focus on development finance, especially vast forest carbon offset deals. Several low-income countries with fossil resources are hoping to develop them in time to exploit a declining market; while others such as Colombia and Ecuador are exploring ways to transition to new industries before the price decline.

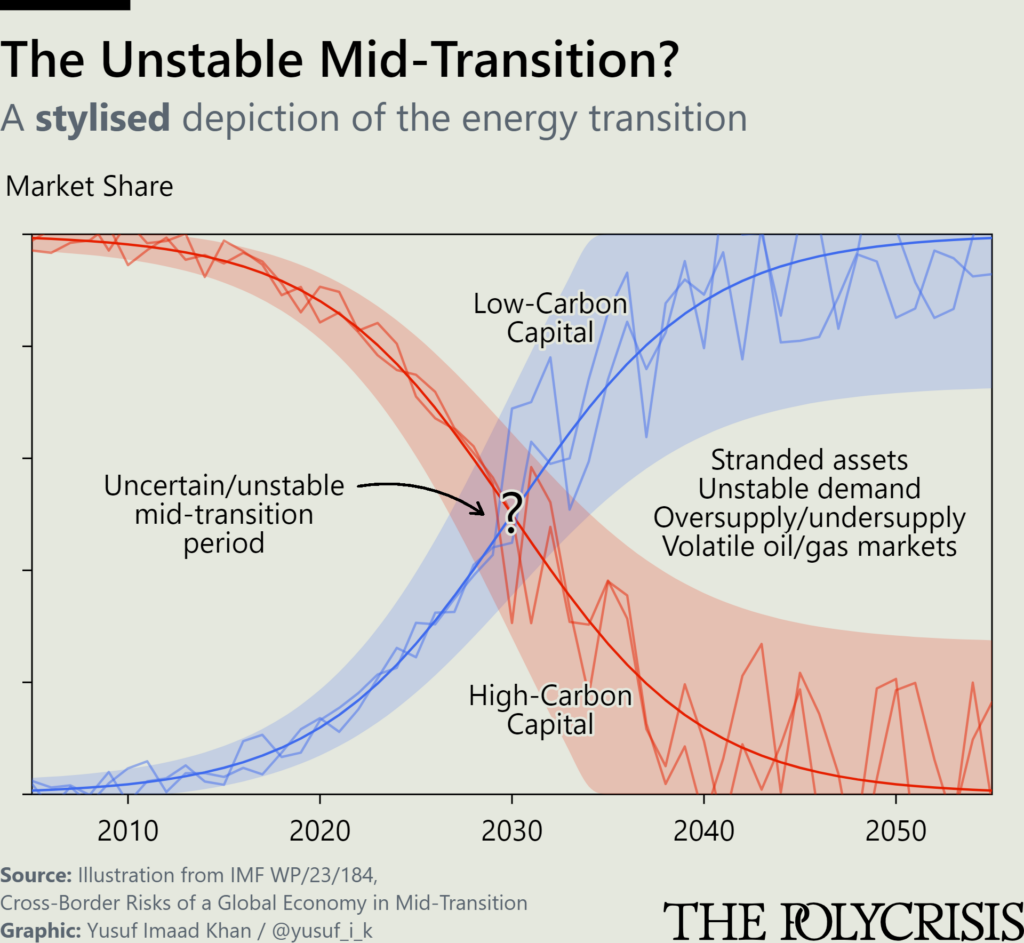

Today fossil fuel markets still involve great power plays between producers and consumers. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine was funded and buoyed by its export earnings and its apparently captive market for gas; the response by western countries also sought to weaponize fossil fuel markets through price caps and prohibitions on shipping insurance. Fossil fuel demand can change much more quickly than production, which—for oil in particular—expands slowly and capital intensively, and retrenches painfully for both sovereign and commercial producers especially those that rely upon higher prices. This lends itself to lumpy, chaotic pricing shifts, captured by the phrase “the mid-transition” developed by Emily Grubert and Sara Hastings-Simon. A recent IMF working paper, co-authored by one of our panelists, William Oman, applies this concept to cross-border relations to produce a framework that suggests both winners (China, India, Japan) and losers (Saudi Arabia, the US, Russia).

Every country, whether a net supplier or importer of energy and transition minerals, is grappling with the new world.

To discuss these issues, we convened a panel with Amy Myers Jaffe, Morgan Bazilian, William Oman,1 Alex Turnbull, and Adam Tooze. You can watch the full discussion here. The following transcript was edited for clarity.

A discussion on the geopolitics of a transitioning global energy system

ADAM TOOZE: The theme of the panel could hardly be more topical. We are facing something completely new, a world which is now embarking on an energy transition in various messy, incomplete, but nevertheless highly dynamic ways. Our task for today is to begin digging into the geopolitical questions that arise from this.

Some of the questions that immediately arise: How do we think about who the winners and the losers are going to be? What are the prospects for various types of mineral-exporting countries? How does a world with terminally declining oil demand look? Getting into the weeds, we have to speak of an electric vehicle (EV) shock. This is happening as fast as anyone anticipated it could possibly happen, and in very dramatic ways—driven, of course, by China. How do we imagine a new generation of EV-centered subsidies playing out? What does the future of a more distributed energy system look like—one which doesn’t rely on the hunter gatherer model of discovering fossil fuel reserves, but instead is centered on farming wind and solar power?

AMY JAFFE: I’m a big fan of Emily Grubert’s concept that we’re starting to build out the new energy system, but we haven’t integrated it or figured out how to get it to work well with the old energy system. I would say that oil demand itself is not going to fall evenly—there’s still a lot of places where oil demand is rising. The bottom line is, as we move forward, oil has become less inelastic. In the past oil served certain functions—especially in vehicles, but also in certain petrochemical sectors and other sectors—for which there was no substitute. Therefore prices could go way up and stay there until somebody drilled for more oil. But today with the digital world, I am able to own an EV. And even if I don’t own an EV, there is a strong possibility that I know someone who can give me a ride with an EV or that I can access a ride-sharing service with an EV. Individuals and communities can now actually move away from oil.

But we have a problem, which has arisen from the invasion of Ukraine. We’re now at the fiftieth anniversary of the OAPEC oil embargo, but we’re still not out of the woods: if OPEC+ pick a price that’s too high and we fail to damp down the inflationary pressures, high interest rates are going to crash the housing market in different locations. We could see a return of a pretty dire picture if we don’t get this right.

I want to make one more point as we’re going to delve into metals. When you put a metal in my vehicle or in my virtual power plant setup, I’ve got to have it there probably for a decade. And then—because we’re talking ten years from now—I’m going to be able to recycle it. The US Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) is giving out billions of dollars for recycling of metals, and Vitol and some of the other big commodity traders are investing in recycling of metals as well. People want to argue that Chinese government controls these metal assets for processing, or that there’s a lot of these metal resources in this country or that country, but it’s not the same as oil and gas because you don’t burn it in one minute and then it’s gone forever.

We need to move away from that storyline—which I do believe is a very oil industry-oriented storyline—that somehow these metals are just as bad. I’m not saying metals don’t have environmental impacts that need serious consideration, but it’s really a very different kind of thing. People said we’re going to run out of lithium—now there’s been a world historic find of lithium in India, so much that they’re not going to need to import lithium from anyplace else. Like oil, I think metals will suddenly appear in ways we didn’t imagine they would. It’s a commodities market, and commodities have a way of showing up when somebody needs them.

TOOZE: Thank you so much for taking us into metals, oil, and finance all in one fell swoop. Morgan, which bit of this subject do you want to pick up for us?

MORGAN BAZILIAN: I’ll say five things. The first is that, in 2008, I co-wrote one of the only textbooks that’s been written on energy security. It has the catchy title of The Analytical Methods for Energy, Diversity, and Security. In the second paragraph of the introduction, we warned about the dependence of Europe on Russian natural gas. It was obvious then. There were meetings of ministers happening all over 2008 to 2009 about transit through Ukraine.

The second is, I co-authored wrote a paper that was published in Nature, resulting from a scenario exercise we did for the German government—not the German Department of Energy or Economics, but the Ministry of Security, similar to the US State Department. In the paper, we came up with four different scenarios, wildly different outcomes, of things like oil versus renewable energy; we also included other fossil fuels and different kinds of energy. The most important outcome was that there would be—will be—winners and losers. It’s very easy to make goals. We see that all the time. Many of the world’s powers—maybe most—now have net-zero climate goals. In fact, Russia brought their net-zero goal to the climate talks six weeks before the invasion of Ukraine. And so one can be rather cynical about the value of making high-level political statements. The planning is extraordinarily difficult—not just politics, but engagement with communities and funding.

The third is, I co-authored a piece that tried to look at security in a different way. I believe we coined the term “actorless threat,” which was a way to look at how you move, at least in the US, from a military Carter Doctrine perspective on security toward a situation where there’s no place to put military force, per se—there’s nowhere to target a missile. The examples we gave were the COVID pandemic and climate change.

The fourth has to do with critical minerals. The straw man argument that we have to make an analogy between oil security and mineral criticality is long debunked. But a few things in the critical mineral space are important to keep in mind. One, it is true that China dominates, and the US is not going to catch up in the very short term—not just because China has planned for this over the last three decades, but also because they’re not waiting for us. They’re presently making enormous investments in those sectors. Two is that you have to think across supply chains and critical minerals. No one needs the raw minerals themselves; the value for the economy goes up as you move along the value chain to advanced manufacturing. The markets for these different things are minute, in most cases. They have very poor price signals, and they’re not liquid. Those are significant threats. There’s plenty of the stuff in and on the Earth, but there are challenges to using it.

The final thing I’ll say is that, at the Payne Institute, through satellite data, we see light and we impute heat. In other words, we calculate heat through basic equations of physics, and through that we have really a very different way to look at how energy security, national security, and human security are being reshaped. That has long been the purview of the intelligence community and the military; now those functions are, as an example, at a public university in Colorado.

TOOZE: Thank you so much Morgan. That was fascinating. So, William, I’ll call on you, then Alex, and we’ll start going back and forth.

WILLIAM OMAN: There’s been a lot of focus on the ways in which geoeconomic fragmentation and geopolitical rivalry matter for the prospects of global decarbonization; however, as my coauthors and I argued in our “Mid-Transition” paper, that there’s been much less focus on the potential impact of global decarbonization on geoeconomic fragmentation and geopolitical rivalry—the other way around. We build on the concept developed by Grubert and Hastings-Simon of the mid-transition, which we interpret as a volatile, unstable, and potentially chaotic period where we have the fossil-based energy system persists even as low-carbon technologies rise. We have some modeling results that show very large changes in energy exports, trade balances, and GDP among G20 countries at the 2030, 2040, and 2050 horizons.

A main conclusions of our paper is qualitative: the world economy may be entering this mid-transition, unstable phase. This is happening even as climate impacts and other impacts of the polycrisis worsen. In this context, there’s a real risk of the world economy being increasingly exposed to cross-border risks of an economic and financial nature, which would deepen fragmentation. This could ultimately disrupt national economies, global trade, and potentially even the international monetary and financial system. That would, in turn, interfere with countries’ ability to decarbonize.

In my view, the focus on winners and losers is missing a very big blind spot, which is that we’re facing a huge collective action trap related to political economy. Neither the middle classes in high-income economies nor the majority of developing economies have the means in the current international institutional configuration to achieve the transition. We are seeing the simultaneous occurrence of significant costs related to climate policies and rules of the game that prevent many countries from achieving a rapid transition. The risk is that this could give rise to a significant political backlash, with the rise of populist and extremist parties. We’ve already seen this recently in Germany, where regional elections over the summer were won by AfD, the far-right party; also the U-turn of Rishi Sunak.

TOOZE: Thank you. This whole mid-transition issue is one that we’ve got to come back to. Alex, can I ask you to wrap up this first round of comments?

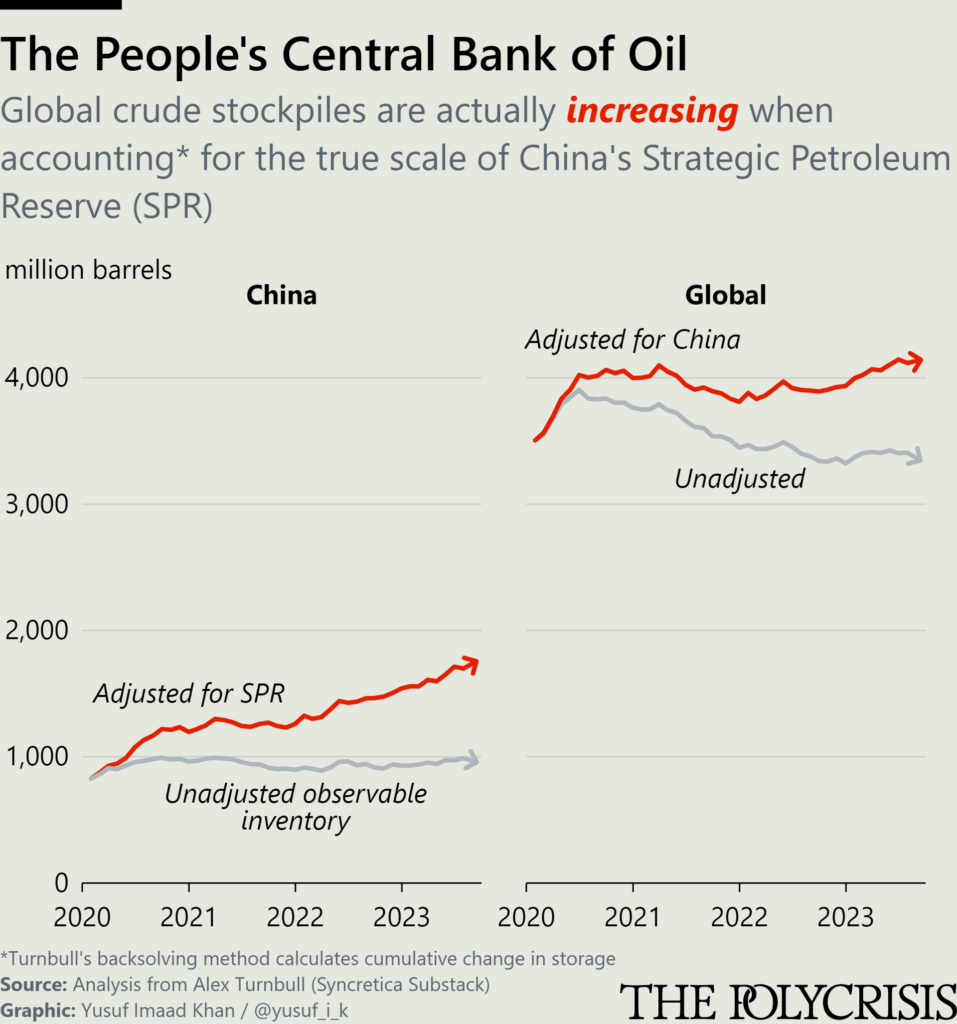

ALEX TURNBULL: With the Australian National University (ANU), I’ve been modeling the details of these mid-transition dynamics, particularly with respect to China. China is in some respects far more advanced in activities like stockpiling, though they are loath to disclose these things, which leads to some interesting forensic econometric work. We have been modeling how China has been reconfiguring its internal logistics to essentially exit coal markets, and how their changes in grid investments could immensely accelerate the process. We are also trying to pick apart what exactly China does with its strategic petroleum reserve. China has really deep capacity, though its disclosure is not excellent, which makes it very hard for other countries to coordinate their behavior in response or anticipation.

There’s also the issue with China—much like a lot of other countries and particularly the US—where it is a large domestic producer of a lot of fossil commodities, but also newer energy products. The issue is that you can have this very turbulent dynamic where a country can previously be a large importer of things and then make a very rapid phase shift to self-sufficiency, both policy-led and in response to changes in demand dynamics. This, of course, has very big macro implications for anyone who trades with China in commodities.

This mid-transition is almost, in physics terms, a phase shift. Unpredictable and nonlinear, it leads to very peculiar dynamics, where Europe can be absolutely hurting for gas one year and then swimming in it the next. It’s a volatile period.

In the stockpiling work, I’ve taken a cue from China’s State Reserve Board behaviors, which offers a model for how other countries can achieve a smoother supply growth of these critical transition minerals. Having worked on, I think, seven lithium bankruptcies over the past twelve to fifteen years, it seems quite clear to me that the way we are not managing this challenge optimally this in the West.

TOOZE: Thank you so much, Alex, for that perspective from the market. Sitting here with my historian’s hat on, I’m tempted to paraphrase Keynes. In the long run, are we always going to be in the mid-transition? I can understand why we need transition thinking; what I’m really puzzled by is the idea of the “mid.” That seems like a teleological construction that implies that we know that we get there, but you all are saying that the transition we’re embarking on is turbulent and there are many obvious points of resistance.

JAFFE: I love how you framed it because I think you’ve really clarified down to the nub. I wanted to throw out an example from the state of California, which I think is further along in the so-called mid-transition than many other locations—even more than China. Because even though, as Morgan correctly points out, China has been plotting this line for themselves for decades, they are still highly dependent on coal—are in fact one of the world’s largest importers of oil. They’re buying LNG from the US as well. Despite our complicated relationship, they have ponied up even more for the new LNG terminals than the Europeans.

California seems to me a microcosm of what can go right and what can go wrong. One of the things that comes about in the mid-transition is that companies take different strategies—they have to decide what to do, and that’s influenced by what they’re forced to do by policy. California has this policy, which seems to be quite effective in terms of implementation—the low-carbon fuel standard, as per which fuel providers have to show increasing decarbonization or purchase carbon credits, which will get more expensive over time.

California is a weird gasoline market. Theoretically, you could ship in gasoline from Singapore or some other location, but there’s a limited number of ways you can bring it in by pipeline, which is the way most fuel moves around. They’re a little bit of an island nation in the sense that if a refinery breaks or something goes wrong, it has an instant price impact.

In California, a few of the refinery players have realized that as people move away from oil, a race emerges between those left with market power and governmental efforts to get people into electric cars and other kinds of transport solutions. The whole thing has blown up into a political scandal about this premium for gasoline prices in California, which is not really a direct result of carbon pricing or anything like that but more a symptom of the mid-transition. Because you have had refinery closures, there is market power.

A question arises: Are we going to say that the refineries are utilities now, keeping them open until there’s enough people to move? As Morgan also correctly points out, there’s also a justice issue. Are we going to accept a situation where people who are wealthy and have EVs or other means of transportation do fine, but those with an old vehicle that needs gasoline get socked with very high gasoline prices? Even though they’re further ahead on electric car deployment, boast a higher percentage of renewable energy, and are doing really well with batteries, a mismatch may still be brewing—a power struggle between the state government and refining industry over the path forward.

TOOZE: William, when you talk about your mid-transition trap, how deep is that trap? The mid-transition concept has this incredibly strong teleological implication that we can define the middle. To me, it’s a little bit like the interregnum idea which floats around critical political economy that we’re between hegemonic structures. I’m always tempted to ask, what convinces you that there’s another one coming? In your modeling, how destabilizing is it to the overall narrative of transition?

OMAN: We argue the transition is actually more of a transitory phase—not in the traditional sense of decarbonization policy discussions, where its basically presented as a controlled trajectory on a certain timeline with a certain shape of the curve. We interpret it in a slightly different way, as this volatile, unstable, and potentially even chaotic phase characterized by the persistence of fossil-based energy systems and the rise of certain low-carbon technologies.

We see the risk of a trap because of numerous cross-border feedback loops. To give you one example, the materialization of physical climate risks hit hydropower in Latin America, directly leading to a buildup of fossil infrastructure to offset that. Multiple countries face sovereign debt crises arising from different sources, which have led to an inflow of foreign direct investment into extractive sectors to address these countries’ foreign currency needs. There are also huge gas projects in Argentina. The climate crisis will continue to be fueled by all this.

We also have in the background these biophysical dynamics going on that are, in principle, irreversible—contrary to the crises that we’re all used to thinking about such as the Great Depression, which can ultimately be reversed. That’s why I think there’s a blind spot on this discussion about winners and losers—because we will all be losers, in an absolute sense, if the current configuration persists. That is because we are likely to see these very significant binding constraints materialize both on resources and supply chains.

Regarding the policy implications, I want to speak about international coordination and cooperation, which has become a bit of a cliche. Regarding critical minerals, do we need an international agency? The International Energy Agency (IEA), World Bank, and International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) are all jockeying for leadership on supply and prices; however, I see this goal as a very concrete policy agenda for international cooperation. In the context of geopolitical rivalry, China and the US in particular make cooperation extremely difficult, but I think this has to be a kind of working hypothesis for a policy agenda. Because at the moment, I don’t see this being at the center of policy discussions.

TOOZE: Alex, in the markets do you see solid conviction around the 2050, 2060, 2070 horizon for decarbonization? Or do you see the markets pricing for some sort of mixed and very unstable environment?

TURNBULL: No-one cares about 2050, not really even in bond markets.

JAFFE: Well, I think the question is: Are people today making capital investments with their eye out in a distance or only on the next couple of years?

TURNBULL: I’ll give you an example. It is very hard to fund pumped hydro assets right now because they are five- to seven-year capital works projects, which are predicated upon diurnal price cycling spreads. The good news is that batteries have gotten a lot cheaper, and there’s a number of other, more modular long-term energy storage options. In Australia, we’re seeing this mid-transition get to a good place. During the Ukraine shock, electricity prices moved in sympathy with fuel costs, namely coal and gas. But now enough people have installed solar—utility but primarily residential—and the battery supply is large enough that gas burns on the Australian grid are probably going to drop by 50 to 60 percent.

From an industrial organization point of view, Australia is a little bit like Canada. Not as big and competitive a country as the US, it’s a little bit clubby. People tend to extract rents and engage in portfolio bidding. That’s going to completely break down because you suddenly have more players with peaking capacity, and that’s probably going to destroy pricing power on the market. Prices are going to be essentially pinned by a marginal cost of solar, plus or minus whatever spread a battery needs to make on a diurnal basis.

In oil and energy markets, the media coverage sometimes makes me want to scream. The reason is, it’s very hard to observe China’s petroleum stocks because they don’t like to report them. You can get it from satellite services for the above-ground stuff, and then for the below-ground there is the strategic petroleum reserve. The first rule about the strategic petroleum reserve in China is you don’t talk about strategic petroleum reserve—a lot of consultants who used to provide that data have been harassed and left China. But you can back it out by looking at stock flows.

The funny thing is everyone talks about oil and ventures being super low right now globally; however, if you zoom out of the accounting anomaly in China, we’re probably at record stocks. China has been building up its petroleum reserves like crazy during COVID. As soon as they stopped, the market kind of fell out of bed. In a weird way, China’s been acting like a covert central bank of oil, a fact which is not very well appreciated.

JAFFE: Are they trying to help the Russians? I mean, they’re taking oil from the Russians.

TURNBULL: They have a really interesting problem. They had structurally declining diesel demand because they moved a lot of coal transport from trucks to rail. As a result, diesel cost per kilometer went down about 75 percent. Consequently, diesel demand fell, but it’s gone to the moon more recently because they’ve been buying all this heavier Russian crude and running it. Their real estate sector is so sick, though, they’re not able to use it.

My estimate is they’re sitting on about 200 million barrels of diesel stocks right now, which is quite a lot. But then just a couple of weeks ago, they decided not to bump their quota for exports. They’re either planning to blockade someone in the not too distant future, or this is just really incoherent policy.

JAFFE: A lot of people say that they need diesel for reasons other than their economy.

TURNBULL: Yes, and one thing I’ve been mulling over as we model things like coal and the grid build-out is, when you have a lot of pumped hydro and a lot of distributed solar, you don’t need as much gas for peaking, so maybe their LNG demand falls quite sharply. It hard to draw conclusions about Chinese governmental policy, as the data is not easily available. It is occasionally profitable, but not exactly easy work.

JAFFE: One of their motivations for going green, quite honestly, was that the US now has its own oil. The US had this big boom with shale, and still has a thriving refining industry. The strategy of China going green was to be much more self-sufficient. That’s part of why it’s hard for them to commit to closing coal. And then the question is, if I’m building up all this oil, and the US has its own oil, why did I feel I needed all that oil?

TURNBULL: They stockpile everything, and they are honestly great traders—maybe not as good as Glencore, but close.

JAFFE: They’re stockpiling oil at a high price, no? They think it’s going higher?

TURNBULL: They built most of their SPR over 2020 when transport demand imploded. More recently, over the pas three, four weeks, they have completely stopped importing. It’s like the Bank of Singapore managing a trade-weighted band for their currency—China’s effectively got a band for oil that they are quietly enforcing, which I think is kind of a good thing from an inflation stability point of view.

TOOZE: Standing back from this, are we basically saying that the importing side drives this industry over the medium- to long run? In these transition stories, it’s the demand side that’s really king, right? It’s all very well to have your own oil, but in a sense it could just be a kind of a giant pile of stranded assets, especially if they’re expensive.

TURNBULL: It’s good to have stocks so you can manage price volatility. China has been significantly growing its oil production and gas production in the last couple of years. Both are good things to have in order to manage price. A lot of transition assets are quite long-dated investments; wind and solar are about twenty-five years of cashflows. So if you can manage the cost of capital, that’s desirable for allowing the transition to occur. It’s an interesting tension, though—if China’s trying to enforce a price band of $70 to $90 per barrel, and Saudi Arabia requires, to break even fiscally, $85 to $90 to $95. It is also a question of, if you are an oil exporter, how do you fund your transition to the next thing? Whatever Saudi Arabia may want to export in fifteen years, it will be affected by buyers managing reserves in a different way. There’s lots of funny national interactions that are occurring, which are perhaps not as well publicized as they should be.

TOOZE: I want to spin around and ask about copper. In the news coverage of minerals and metals, lithium is the heartbreaker—everyone expects it to make money, and then you go bankrupt because somebody discovered another lithium thing. If you look at the world through the lens of the Financial Times or The Wall Street Journal, however, the vision you get is a looming issue in copper because the expansion of capacity has not been there. Existing mines in Latin America are unpromising for political reasons, and the investment lags on these things are gigantic. If there’s one thing we feel reasonably confident about, it’s that we’re going to need a lot of copper, only a part of which can be acquired through recycling. Allowing for the fact that, in general, we buy the market dynamics in innovation and recycling and everything else, is copper the exception to that story? Or is that another kind of fallacy of commodity journalism?

BAZILIAN: I think about all these discussions in terms of priorities. There’s almost no country in the world where climate change is an actual political and social priority. And if you don’t have something prioritized then you’re not going to get very much done about it.

From both a public policy perspective and an investment perspective, we can do the right thing for the wrong reasons. When we think about critical minerals, the only reason that they are being talked about it—at least in the US, and to a large degree in other OECD countries—is because of the angst with China. It’s not because of some mid-transitions struggle or climate change imperative. In the US, of course, that means it’s one of the only things that’s remotely bipartisan. You could see that in the Congress if it were actually functioning.

Down to copper: Copper is very important for energy transitions; it’s very important for electrification, especially. It also happens to be incredibly important for munitions. Is there some sort of dearth in copper? No, there’s no dearth of resources of copper. But there are issues in countries that have copper—including political conflict the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Everyone talks about the DRC in the context of cobalt. But cobalt is a secondary mineral—you mine for copper, not cobalt. There are political challenges in Peru, Chile, the US, and on and on.

Interestingly, copper is not on the US Geological Survey critical minerals list. It is on the newer list that came out of the Department of Energy. That doesn’t mean it’s more or less critical. Of course it’s critical, and you’ve had some famous energy people like Dan Yergin write reports with S&P about it recently. Will it halt the energy transition? No, it will not. But people need to keep in mind that some people are more concerned about using copper for munitions than they are for transmission lines. I come back to my point about priorities—if you don’t understand where the priorities are, then you’re very unlikely to come to a reasonable answer or solution.

TOOZE: I take that point. It is sobering to scan the world’s governments and ask who, in fact, is taking this seriously. Is there an energy expansion happening? Or is it the same old process, with new and added sources being thrown into the mix, pell mell? William, you had something you wanted to add?

OMAN: I wanted to pick up on what you just said about energy symbiosis, the additive dynamics between energies and energy sources—which, I think, is another big blind spot in discussions. Independent of any trade and geopolitical tensions between the US and China, Europe faces a really steep challenge in terms of acquiring critical mineral. Europe’s supply of critical minerals contains only 3 percent local production; the target is to get to 10 percent by 2030, and to 40 percent of refining of metals by 2030. This is a huge challenge. There is also the fact that the EU taxonomy for sustainable activities does not include mining activities, and the related Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation requires that investors explain how their investments take sustainability into account, with the implication being that investment is not being steered toward the decarbonization-relevant mining sector. This is despite the fact that technical experts cited aluminum, copper, nickel, cobalt, lithium, lead, zinc, and precious metals as being essential for the transition. There’s a real contradiction there, with pretty big ramifications.

It’s important to realize that copper is not just important for the energy transition, it’s part of the vitamins of the economy. If we continue on the current trajectory of expanding consumption at the global level and gradually increasing income levels, this implies massive needs for copper for reasons independent of the energy transition. And speaking of EVs, there’s some big challenges that are being sidelined in discussions. The CEO of Stellantis recently said that if EVs are not affordable, you can’t leave a big chunk of the US middle class without freedom to move around. There are rumors that European Commissioner Thierry Breton reassured the auto industry in Europe that they would be able to export internal combustion engine vehicles to developing economies. The pushback on EVs comes from those saying the grid may not be stable enough in many developing countries, putting aside the question of affordability.

One last point on energy symbiosis. Vaclav Smil pointed out in Energy and Civilization: A History (2017) that a fundamental fact of energetics is that every transition has to be powered by the intensive deployment of existing energies and prime movers. It’s important not to underestimate the extent to which coal is needed to produce steel, which is currently needed to produce EVs, and so on. We may be able to decarbonize steel at some point, but we are not there yet.

JAFFE: Morgan raises an important point: What is your priority for different materials? And how might that manifest itself in a war situation, as opposed to during peacetime?

Part of the storyline of the Industrial Revolution, then followed by the World Wars, was that there were a large number of electric cars in the US in the 1910s. There was a lot of metal that was needed for munitions, as was mentioned above about copper. The US president deployed Ford Motor Company and other organizations to provide gasoline trucks and chassis and change their assembly line from electric to fuel-based vehicles to facilitate sending those vehicles to help Europe in the war. A war could actually be a definitive feature in shuffling away from a technology if it requires taking up materials.

TOOZE: I’m trying to pull together the strands of this fascinating exchange. We started out with a kind of script, which was energy transition—we are mid-transition in regards to falling oil demand. And what I’m hearing is something different and more complicated.

Picking up Morgan’s point, maybe the energy transition is really no one’s priority. The real priority is great power competition logic, which energy technologies may play into. There’s every reason to think the Chinese government would, from their position in the world, have a substantial interest in diversifying their energy sources and stockpiling oil and minimizing their dependence on seaborne routes. But the way Alex described it, it’s not really a one-way street. It’s not an unwinding. It’s actually a kind of strategic play between the Saudi and Chinese governments.

And then we have a kind of general skepticism about California, a warning about the fragility of Europe, and Morgan’s point about how, really, when the chips were down, everyone clustered around fossil again. And then from William, a series of questions about the fragile states in-between. Because as complicated as the status quo is, the world that comes next for many of them looks even more complicated.

TURNBULL: You’re the historian, but I’m not sure state behavior and priorities really change much, ever. When you throw a new technology in the mix, whether that’s nuclear weapons or cheap renewables and storage, all that changes is the lay of the land in terms of priorities and edges countries can get.

Given the current trade contention over EVs—if EVS exist at a reasonable price point and people are willing to purchase them—companies, particularly like Geely, really cannot compete with the Volkswagens. So they just said, alright, if we’re going to be relevant, we have to go all in EVs. There was definitely a good amount of state support, but there was also a calculus that we’re not going to have an export sector in this space otherwise. And of course, they’ve succeeded wildly there.

I’m not sure priorities really changed that much; I think Morgan’s absolutely correct on that. But once these technologies get to certain price points and availability, people have to deal with them. They have to integrate them into their calculus one way or the other.

TOOZE: How bad does the climate crisis have to get before it has impact on these systems? William reminded us that we’re all losers unless something acts. Implicitly, what we’re saying is that, for all relevant purposes, over the next ten to fifteen years, the climate crisis is actually bracketed for the big actors in the system.

TURNBULL: I would say that the bad thing about the climate crisis is that hydrological cycle intensification tends to destroy infrastructure. The good thing about renewable technologies is that they tend to be sort of anti-infrastructure.

The Panama Canal water levels are quite low right now. Shipping is starting to be constrained, and most global shipping is just moving around joules. That means we’re getting to a point where there’s a real confluence between bookish security people and people that care about climate.

JAFFE: Europe installed a giant amount of renewable energy. They put in solar, and Germany added batteries. They made announcements that they’re going to triple their targets for renewable. So I think the war actually hastened the transition, not the other way around. It just set back last year’s emissions for some temporary fixes.

TOOZE: Morgan’s hypothesis becomes more relevant when you ask the question: Can the most progressive government in Europe get serious about heat pumps? In fact, that is very difficult. But Morgan, you wanted to come in?

BAZILIAN: I liked what Alex said about this convergence of interests. That’s why you see the military in the US talking about climate and security. And what Amy said—of course, it’s exactly right that you asked, what will it take to take climate seriously? War is one thing. But to go back to my point, we can use things people really care about—like security, like air and water pollution, and like economic development—as prime motivators that will help the climate as well. You can get some of these happy coalitions. But if you insist on transacting everything through a climate lens, it is, in my view, not the most powerful nor the most effective way to make those transitions.

TOOZE: There are some constituencies where you may be able to sell climate head on, but in the vast majority of places, it’s got to be in combination with, exactly as you put it, either pollution, or cheap energy, or development, or national security. It’s got to be coupled.

The views expressed by William Oman do not necessarily represent those of the IMF, its Executive Board, or IMF management

↩

Filed Under