The majority of countries in the world have some sort of fiscal rule: an institutional constraint on fiscal policies to discourage government overspending and reduce political influence on state expenditure. But these rules have their own politics. As Clara Zanon Brenck and Pedro Romero Marques write in their recent Phenomenal World essay:

Fiscal policy can help resume economic activity and maintain social stability—a precondition and ultimate policy aim of a social democratic pact. But when rigid and ostensibly apolitical fiscal rules moralize the public spending debate in favor of sound finance, responding to changing economic conditions with blunt compliance mechanisms, such a path cannot be pursued.

In October, Zanon Brenck and Romero Marques were joined by Max Krahé for a Phenomenal World panel on the politics of fiscal rules in Brazil, Germany, and the European Union. Romero Marques is the research coordinator at MADE, the research center on macroeconomics of inequalities at the University of Sao Paolo. He has a PhD in Economics from the University of Sao Paulo, and his research focuses on the distributive aspects of contemporary Brazilian financialization, as well as the international monetary system. Zanon Brenck is an associate at MADE and holds a PhD in Economics from the New School. Her work focuses on inequality, debt dynamics, and taxation. Krahé is the Research Director of the Dezernat Zukunft, which he co-founded in 2018, and received his PhD in political economy from Yale University.

The conversation, moderated by Alexandros Kentikelenis, analyzes the evolution of fiscal management over the past two decades, in the aftermath of the Eurozone debt crisis and the resurgence of the Workers’ Party ( the Partido dos Trabalhadores, or PT) in Brazil. The panelists discuss the increasingly legal nature of fiscal rules, their relationship to party politics, and prospects for reform, demonstrating how technical debates hold major consequences for the working classes. A recording of the event can be viewed here. This transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

A discussion on fiscal rules

Alexandros Kentikelenis: The fiscal rule is a long-lasting constraint on fiscal policies through limits on budgetary aggregates, like limits to the fiscal deficit. The IMF, the world’s guardian of fiscal orthodoxy, says that “fiscal rules typically aim to correct government incentives to overspend and to ensure fiscal responsibility and debt sustainability.” We can recall limits of 60 percent debt-to-GDP ratio or 3 percent deficit limits that many countries did not comply with in the EU. Fiscal rules are prevalent across the world.

Fiscal rules are intended to provide incentives for governments not to overspend—especially during good times—but they also have key drawbacks. Strict fiscal rules may reduce the scope of governments to adjust policy in response to unexpected shocks like economic crises. Equally importantly, they may limit available spending necessary for making economies more resilient, not least, to the risks posed by climate change. In Latin America, evidence shows that public investment is the category of spending that is most adversely affected by fiscal rules. For these reasons, understanding the political economy of fiscal rules is more important than ever. Fiscal rules form part of the infrastructure of contemporary capitalism, both in the global North and in the global South.

Max, can you speak to the role of fiscal rules in Germany?

Max Krahé: The history of Germany’s fiscal rules begins with debate in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Germany used to have a golden fiscal rule that said the state had to balance the budget. However, the state was allowed to enter into a deficit through the volume of investment spending. The Constitutional Court was frustrated with this, because nobody could delineate what precisely was an investment and what wasn’t. In 1989, the court ruled that the state had to provide a more precise definition. While this led to some reforms, there were no significant changes. The Maastricht Treaty process occurred in parallel to this domestic German contestation, linking notions of German reunification and European Monetary integration. The Maastricht process introduced quantitative fiscal rules—the famous 3 percent extent limit on annual deficit and the 60 percent on debt-to-GDP-ratio. As history moved forward, and frustration with the German fiscal rules bubbled up again, another ruling by the German Constitutional Court later expressed the court’s displeasure with government policy. In the early 2000s, both Germany and France broke the 3 percent limit or deficit. In response, European fiscal rules were reformed to allow a temporary breach of the 3 percent rule, quantified as a 0.5 percent limit on your structural deficit.

In 2006-2007, a commission was instituted to examine German federalism, in particular, how the fiscal relationship works within the federation. The European reform of 2005 had introduced the possibility of a structural deficit limit. In 2008, the Schuldenbremse (“debt brake”) federal constitutional reforms—instituted ahead of the 2009 elections—marked a decisive moment for Germany’s debt/deficit protocols. During the financial crisis of 2008, the conservatives agreed to a fiscal stimulus on the condition that the state harmonized them with the quantitatively precise European rules, as opposed to the loose golden rule of the Constitutional Court.

This moment resulted in the shortened versions of the debt brake, which are still in place in the Constitution, making them incredibly difficult to repeal. In Germany, you need a two-thirds majority, requiring the conservatives, namely the CDU and CSU. The German debt brake is a limit on the deficit that completely ignores debt levels. It has no interest in the debt stock, only in the annual deficit, and it limits the annual deficit to a structural deficit of 0.35 percent of GDP. There’s also a cyclical component: if you’re in a recession, you can spend a little bit more, and if the economy’s doing well, you have to tighten your ship a little bit.

The operationalization of that is a complicated story. Today, European rules have a preventive arm, to prevent countries from getting into trouble in the first place. The centerpiece of that is the so-called medium-term objective. This tells the state to run their fiscal policy so that they have a 0.5 percent of GDP structural deficit. If you’re kind of getting out of hand, this kicks in. This means you have to have a deficit of plain deficits, not cyclically adjusted, that is less than 3 percent, and your debt-to-GDP ratio should be lower than 60 percent. If you violate those rules, an excessive deficit procedure (EDF) will be initiated. Unlike the European rules, the German rules are immediately binding—the German government can immediately be brought in front of the Constitutional Court for breaking the rules. It’s a hard quantitative limit with a legally-binding nature. Breaking the European rules initiates a long and complicated procedure, which involves the political voting of states.

AK: Are reforms necessary? If so, what are their prospects?

MK: In the 2000s and 2010s, the Eurozone suffered from slack, high unemployment, very low interest rates, and very low inflation. All the macroeconomic indicators indicated that there was plenty of spare capacity that was not being used. Monetary policy was at the zero lower bounds, or the effective lower bound. Even quantitative easing couldn’t push the economy to full employment, and instead have side effects on asset prices such as housing. There was a clear case for more fiscal stimulus, but it kept running into the fiscal rules.

While the high-level structure of Germany’s fiscal rules is written in the Constitution, the cyclical component is government by decree—it’s easier to change than the Constitution. We at Dezernat Zukunft looked to see if there’s space for improvement. The way that it currently works is that you have a projection of potential output, and you have a projection of what you expect actual GDP to be. If your projected, actual GDP is significantly below your projected potential output, you have a so-called output gap—that generates additional spending space. Potential output, however, is unobservable, and the calculations involve a high degree of discretion. Depending on the macroeconomic situation, reform ideas can yield significant additional spending space. We’re currently in conversation with the government which has decided to look into research, and we’re also engaged in bureaucratic trench warfare with the relevant civil servants and the relevant ministries that do these calculations. We’re trying to convince them that there’s a better way of doing this.

The European level also has a reform effort around the fiscal rules. The European Commission has tabled a proposal, which would put a new tool in the fiscal rules toolbox. This new tool, the debt sustainability analysis (DSA), originally came from the IMF. It’s worth highlighting the extended timeframe of the reform effort. DSAs are meant to work with spending plans ranging from four to seven years, put forward by member states. The DSA begins at the end of those spending plans. At the end of the timeframe, your debt-to-GDP ratios—projected from fourteen to seventeen years—must be lower. Those projections are going to be extremely assumption-driven.

How do we fix these reforms? The current rules are very strict, but killing this reform effort means that when they come back next year it might be so politically untenable, that this could be a reset button and space could be created for a better version of the reform. If that’s not possible, then at least prevent the worst—Germany’s currently pushing for quantitative benchmark, meaning if you’re not meeting the targets then automatic tightening takes place

We also look at the interest rate assumptions inside the DSA given the long time horizon. Market-based interest rate assumptions bring a risk of doom loops. Let’s say Italy’s expected interest rates look bad, and there’s a DSA. The DSA based on bad interest rates gives even worse results, and the markets look at those results, and drive up spreads even more. To prevent this kind of doom loop, you should not use market interest rates in your assumptions for the DSA.

The framework for DSAs needs to evolve. The current European rules are determined by a so-called output gap working group, staffed by civil servants from various national ministries. Extremely important discussions happen there—they are very technical, but highly politically consequential. It is important to replace that body with something more political and more transparent. These discussions need to take place out in the open, not in the shadows. They must be held publicly and own up to their politics.

AK: Pedro and Clara, can you speak about the debate around Brazil’s fiscal rules?

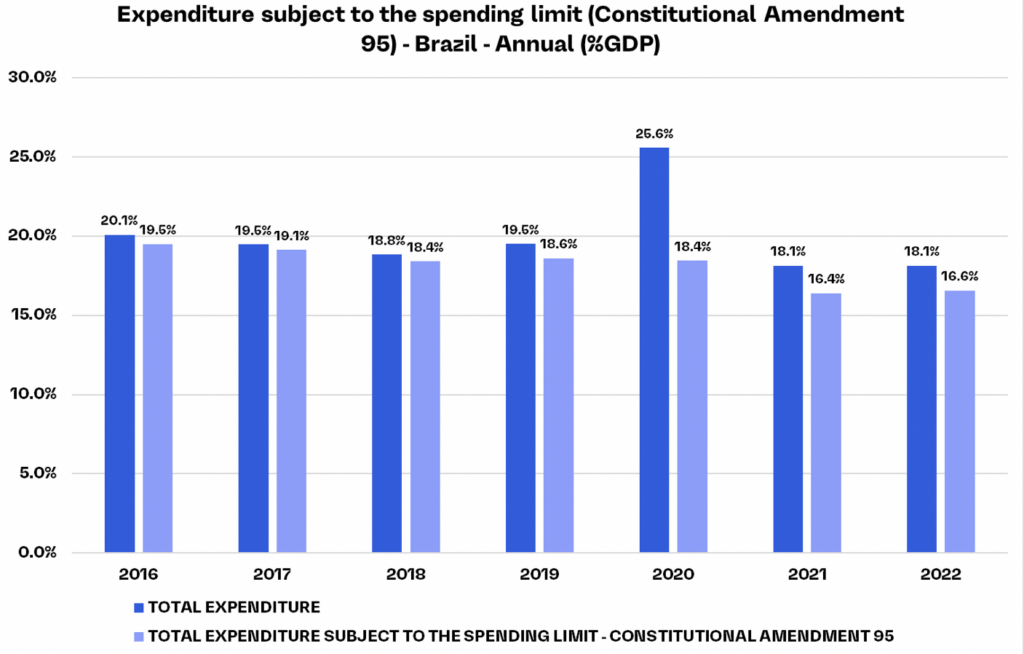

pedro romero marques: Since 2016, Brazil’s fiscal rule prohibited the government’s spending to increase in real terms for twenty years, effectively freezing state spending. Of course, some economists and specialists argued that the state’s finances would not be able to keep up with the state activity with this rule, but the consensus around the difficulty regarding the spending cap only came in 2020 during the pandemic, when it was clear that the spending cap wouldn’t be able to accomodate emergency expenditures. It was already expected that the winner of the 2022 election would propose an alternative—now that responsibility is with Lula’s Workers’ Party.

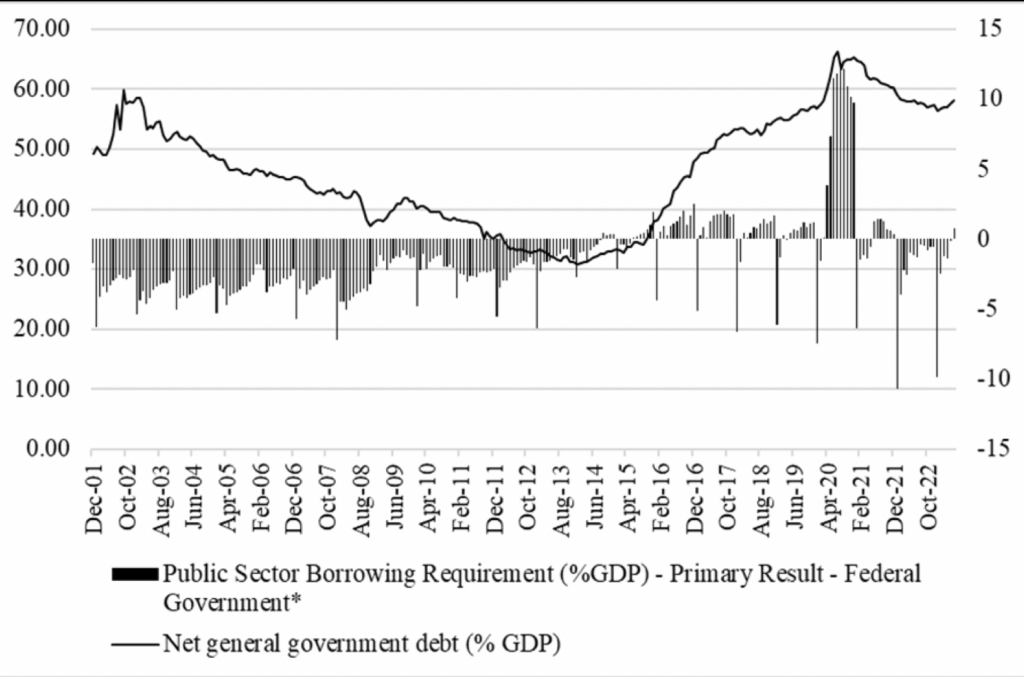

How did Brazil adopt this strict rule? The origins of the spending cap are around 2013–2014 when fiscal surpluses became fiscal deficits in Brazil. The fiscal responsibility law of 2000—not a constitutional rule—was established to complement the inflation-targeting regime in Brazil. It required the government to define fiscal results targets each year, leading to some predictability in fiscal policy. The PT came to power in 2003. It’s important to note that the fiscal responsibility rule was enforced during the whole period of PT rule, with no difficulty in complying until 2013. There were fiscal surpluses, and the debt-to-GDP ratio had fallen. But in 2013, fiscal deficits led to a sharp increase in the debt-to-GDP ratio in Brazil. This mobilized an austerity discourse, motivated by right-wing opposition and traditional media that accused the PT government of being irresponsible and fiscally negligent, despite the trajectory of the debt-GDP-ratio in the decade prior. This discourse was powerful in Brazil; it was a key factor in the changes to Brazil’s political system. It was also responsible for the spending cap approval.

Brazil’s debt-to-GDP ratio and Federal Govt borrowing requirement (Dec 2001 to June 2023)

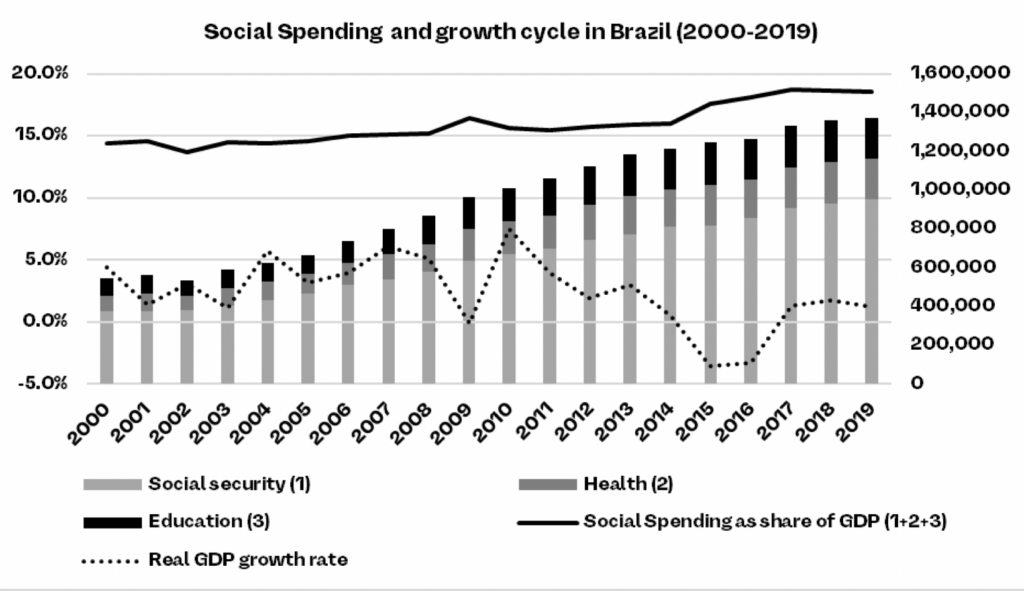

The economic dynamics that caused this pro-austerity surge are very interesting. Looking at the literature, we can see that distributive questions related to the PT’s growth model were important. In the 2000s, Brazil was part of the “Pink Tide” in Latin America, in which left-wing governments profited from international and domestic favorable conditions to increase government expansion in social policy to reduce poverty and inequality levels. During this period, it was common that social spending, both in real terms and share of GDP, increased. The problem began when the economy started to decelerate around 2011. Consequently, the falling revenues and the increasing trajectory of social spending compromised the Fiscal Responsibility Law around 2014–2015.

The trajectory of social spending in Brazil is resilient. This is related to several redistributive mechanisms placed in the Brazilian constitution that allow government spending to increase with policies like the increase of the minimum wage value. The PT’s redistributive model was structurally placed in practice, making it difficult to stop only through politics or policy action.

The actions taken to remove the fiscal structure of the Workers’ Party came in two ways. First, the reaction came politically and President Dilma Rousseff, Lula’s successor, was removed from power in 2016, due to charges of committing fiscal crimes. Secondly, the spending cap ultimately stopped the process of increasing social spending. From 2016 to 2022, a constitutional rule of the spending cap was the fiscal rule in Brazil. In 2022, Lula was reelected over Bolsonaro with a very small margin. He won with a large coalition, but also with a Congress not politically aligned. Under these conditions, Lula is preparing the new fiscal rule.

CLARA ZANON BRENCk: Now, the PT needs to meet certain conditions in order to gain trust from their coalition that they won’t “break the country” again. This discourse around the PT almost “breaking the country” is why we have debt caps in the first place, and the new PT government is tasked with proposing an alternative.

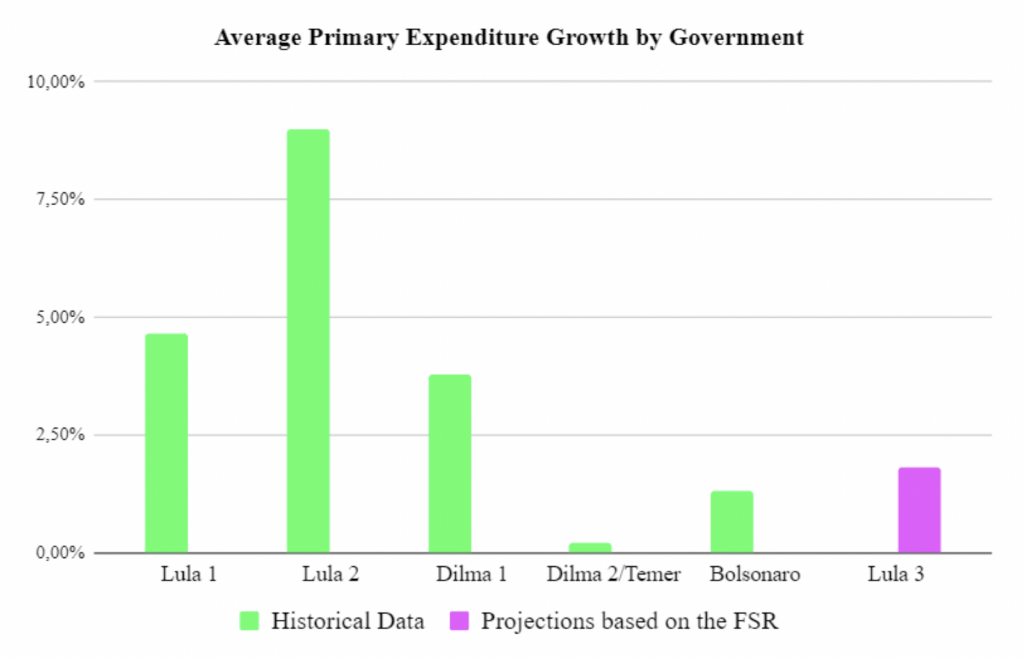

The PT’s new proposed rule is very restrictive. It’s very dependent on tax revenues and contradicts Lula’s promises for greater social spending. The need for social spending and investment will not fit into the new rule. The new rule makes the government dependent on the private sector to foster growth for greater revenues, which will then allow for social spending.

The proposed rule allows real growth that establishes a minimum of real primary expenditures growth of 0.6 percent. It connects the real growth of expenditures to the real growth of revenues, allowing expenditures to grow 70 percent of the growth rate of revenues of the previous year, if the government meets the target. Just like the fiscal responsibility law, the government needs to establish a target for the primary result. However, this target is a bit more flexible, because it has a range that can be + or – 0.25 percent. It’s already a surplus rule because you’re limiting 70 percent of expenditure, but there’s a counter-cyclical mechanism that requires the 70 percent to be within a range of 0.6 percent and 2.5 percent. So if the economy is growing too much, and if your revenues grew 5 percent in the previous year, 70 percent of that would be 3.5 percent, but then you have a cap of 2.5 percent. If the economy is growing rapidly, you cannot increase your expenditures rapidly.

During a crisis, in which revenues decrease, there’s a limit of 0.6 percent. You don’t need to cut expenditures, you can grow 0.6 percent in real terms. Consequently, it guarantees a minimum but it also has a limit that makes this counter-cyclical movement. If you don’t meet the primary target and you’re less than -0.5 percent of your target, then some things must change. Wages of public servants cannot increase. If the primary targets are not met, you also have to grow 50 percent of the revenue growth while also staying between 0.6 percent and 2.5 percent. This is a complicated rule, but it allows real growth, it has a counter-cyclical movement, and more importantly, it establishes a minimum for investment. In Latin America, investment is the first to be cut when we cut expenditures.

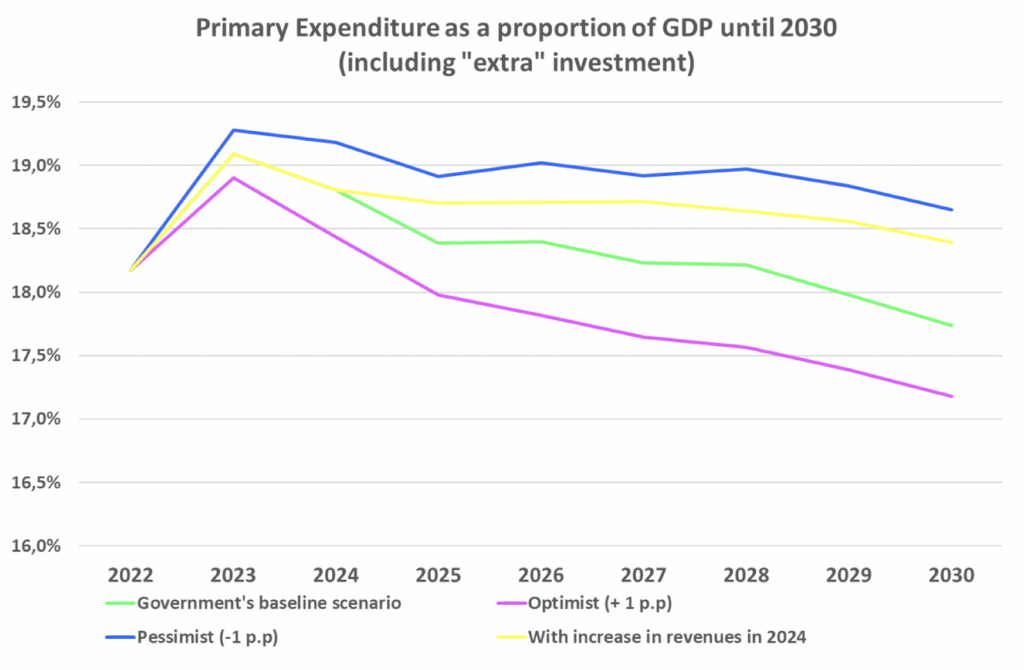

The expenditures of this rule are much lower than the expenditures of the previous PT governments. The government has much less space, and the rule reduces the size of the state related to GDP over time, because it restricts expenditure growth to 70 percent of revenue growth. Even in the more optimistic case of GDP growth, the government is shrinking. The counter-cyclical rule limits the growth of the state.

The size of the State under the Sustainable Fiscal Regime

This is a complicated situation—we will not be able to sustain this rule in the long term, and if we do, we will have to change public spending. The rule needs to change to give a minimum for spending for health and education, or it will force us to cut government benefits such as Bolsa Familia. The minimum wage is linked to government expenditures, because many benefits are tied to the minimum wage. If you increase the minimum wage, public expenditures also increase. If you increase revenues, you also have a rule that connects health and education to those revenues. However, the cap doesn’t allow the overall spending to increase. In the end, investments will be left out, despite the budgetary minimum. You can cut investment if revenues are less than expected.

This new rule is still a very strong austerity rule, but the debate around it was limited. The functioning of the rule was barely discussed, because the consensus was that we needed a rule that restricts government spending in some way. The PT, a government that increases spending and thinks about the importance of government spending in the economy, is actually the one proposing this rule. This shows you the strength of the pro-austerity discourse.

Growth is left to the market, because public spending will not be enough for investment beyond social spending. To finish with a quote from our Phenomenal World essay, “The fiscal rules claimed to insulate fiscal policy from political influence, but this is its own form of politics. So it constrains and reduces the space for the working class whenever in power to influence fiscal policy and pursue distribution redistribution.”

AK: What is so concerning is how fiscal rules exit the state’s fiscal architecture and enter its legal architecture by being constitutionalized. They fundamentally transform the political economy and the ways in which different politicians as well as civil society can engage with these rules. As Max described, the part of the Schuldenbremse that relates to the structural deficit cannot be touched. We can only play with how we understand the cyclical component. The constitutional dynamic yields a set of pressures and politics of its own.

In principle, I agree with Max’s recommendations on transparency and high-level politics, but doesn’t transparency also yield unwanted politics? Of course, we remember the discourse around the lazy Southern Europeans and the hard-working Germans and Dutch people subsidizing them. If we have this high-level political approach, won’t this invite that sort of politics, on which political parties build their entire raison d’etre?

MK: The politics of discussing fiscal roles within Europe has been ugly in the past. Things got very, very ugly in the 2000s, and over the 2010s they improved a bit. It took a lot of time, longer than in the Anglosphere. But eventually, the European discussion has accepted that this form of austerity is destructive. By 2019, we had reached a place where the old fiscal rules were viewed quite skeptically, even in countries like Germany and the Netherlands. During Covid-19, both German rules and European rules were suspended very quickly. Moreover, significant stimulus packages, which, as in the US, led to a far faster exit macroeconomically from the crisis. Politics, especially in the early 2010s, were really ugly, but discussing them made it better over time.

The politics of not discussing the fiscal rules are arguably worse, especially since the rules as they are currently being proposed will not succeed, especially if they’re too tight. There are two outcomes. The first is a terrible rule that would wreck Southern European economies that attempt to stick to them, and in turn create huge resentment in the South. The second option is that these countries fail to abide by these rules, out of realism. In the German and Dutch political sphere, people will say that “no one is sticking to the rules,” this will cause political troubles in the North.

Going forward, I do think that the 2020s look much better for fiscal rules in Europe than the 2010s. I attribute this largely to a pivot in the French position. In terms of public debate, the French have been in favor of more reasonable fiscal rules. However, when push came to shove in the 2010s, they didn’t stick up for this position, because they didn’t really need it and it would have been politically costly. I think in the 2020s, the French are very keen on fundamentally refurbishing the nuclear fleet. That’s precisely the kind of thing that’s very effective, safe, and able to be quickly financed through debt. These are extremely long-lived assets that allow for higher leverage. If the French really pushed for allowing higher leverage, they should have that financial conversation publicly and build trust. Hopefully, we will get better fiscal rules through this process.

AK: Pedro and Clara, you ended by arguing that fiscal politics limit the ability of governments to spend on the working class, ultimately preventing them from living up to the fiscal promises they make during their electoral campaigns. If cuts need to happen, could they be made to disproportionately affect those with higher incomes, who are able to purchase health services or educational services on private markets, thus protecting those of lower socioeconomic status? If the pie of social spending has to remain the same in real terms, is there distributional space?

PRM: You make an interesting point on the changing nature from the economic to the legal character of fiscal rules. I want to make two observations. In Brazil, this legal side was diminishing. Dilma’s government was punished with regards to its budget management, and then the constitutional law in the spending cap that halted our capacity to conduct public policy.

The new fiscal rule is not constitutional, and its punishment is not legal but economic. Both fiscal rules and social expenditure interact with the constitution and are at stake. This new rule is a policy option by the government to endorse social assistance programs, such as the Bolsa Familia, while entering a trade-off, which means that they will probably have to reduce provisions related to public health and education, as well as pensions and social security. This is related to the Brazilian state’s new form of social policy— opting for social assistance and income transfer policy, rather than public health and education in a way that would remind us of the welfare state. This would punish the poorest classes—social assistance can take people out of extreme poverty, they can remain poor. Importantly, Brazil needs free, universal, and well-funded public health and education. To me and Clara, adapting the size of social spending in the new rule will lead to a significant reduction in these provisions.

AK: There’s an assumption around some degree of coordination between fiscal policy, administered by ministries of finance, and monetary policy, dictated independently by central banks. Can fiscal rules work in tandem with monetary orthodoxy, and if so, to what extent? Can we reform fiscal rules without reforming the central bank?

Also, why is Brazil so worried about deficit and debt? Brazilian debt is mostly denominated in Reals, and its domestic debt. Is the concern pure ideology or does it make economic sense? Is the government just terrified of having to go back to the IMF?

CZB: The answers are related. The origin of the fiscal rules in Brazil is the inflation-targeting regime. We had a period with very high inflation rates in the 1990s, and to control that, we had a change in our currency and system that ended with what we call the macroeconomic tripod. This is the inflation-targeting regime on the monetary side, and the fiscal responsibility law on the fiscal side. There’s the idea that you must control government spending to control inflation.

At the beginning of this year, we had nominal interest rates at 13.75 percent, in real terms around 8 percent. The central bank maintained that rate as they waited for the fiscal rule. We have a difficult situation where the inflation-targeting regime holds monetary dominance over the fiscal policy.

If you reduce interest rates to control debt, you change the whole macroeconomic tripod. This would move the exchange rate and affect inflation—our biggest fear in Brazil given our past experiences. Consequently, all the discourse revolves around controlling inflation. The fear of growing debt was employed during Dilma’s presidency for her impeachment. As an ideological discourse, there was no actual evidence our debt was exploding and that we were going to careen off into high inflation. The Brazilian state is quite well positioned economically regarding rampant high inflation, but inflation is used ideologically.

AK: Max, I also wonder if you can speak to the coordination between monetary and fiscal policy. Given the current policy priorities around the green transition, what are the immediate next steps for strengthening the EU’s fiscal capacity? One option, of course, is reforming the fiscal rules. Another option could be to establish a permanent fiscal capacity through some kind of permanent investment fund that may be modeled after the Recovery and Resilience Fund (RRF).

MK: In a well-functioning macroeconomic regime, you would absolutely coordinate fiscal and monetary policies to achieve desired macroeconomic outcomes. In the European context, the European Central Bank (ECB) has actually been a fairly cooperative player. They’ve put in place the “transmission protection instrument”—a protective umbrella for states like Italy, whose interest rates might increase through spreads over Germany—which I’d argue is a key component for improving the European macrofinancial architecture. The ECB has said that as long as you meet certain criteria, including abiding by the fiscal rule, they will buy your bonds. The weight is then on sticking to the rules, which can put states in a difficult position—either you chop your leg off in order to abide by the rules and get the ECB protection, or be at the mercy of the bond markets without ECB protection. The operative issue that’s preventing reasonable cooperation between monetary and fiscal in Europe right now is the fiscal rules. It’s not the obstructive or excessive conservatism on the ground.

I don’t see the potential for a permanent RRF in Germany—both the conservatives and one of the three coalition parties aren’t willing to touch it before 2027. In Italy, a major beneficiary of the RRF, the spending is not fast enough—a result of lack of administrative capacity, which itself owes to a state of near-permanent austerity. I wouldn’t put too much weight on the RRF or RRF replacement. Fiscal rules reform is a much more promising space due to the highly technical nature of its structure. If you get the right players to support Green New Deal financing, you can make projections linked to Green New Deal spending, and so on. I am much more observant of the fiscal rules space.

Filed Under