The last day of June marked the final printing of the London Inter-Bank Offered Rate (LIBOR)—an average of anticipated interest rates among London banks which has thus far served as the benchmark for short term and off-shore lending around the world. For all dollar-denominated loans, LIBOR has been replaced by the Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR), a measure based on real transactions in the US Treasury repurchase market. SOFR is thought to be an improvement on LIBOR because it is based on observable rates rather than anticipated ones.

The shift has initiated cascading regulatory dilemmas in funding and risk markets. In the former, regulators have begun to scrutinize benchmark design with the aim of standardizing the construction of interest rates to avoid the proliferation of unobservable and unfounded numbers. In derivatives markets, regulators like the International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO) and the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) seek to shape the behavior or market actors through the creation of a single centralized clearing house for all dollar based and credit sensitive interest rate derivatives. These two approaches to regulation may conflict: because only large market makers can afford to participate in a centralized clearing house, a shortage of liquidity in the interest rate swap market might limit credit provision in the funding market.

These policies came under scrutiny for their impacts on derivatives and funding markets. But they also affect an additional and far less recognized aspect of global financial markets: the payments system—most wholesale payments depend on the liquidity conditions in funding as well as hedging markets. Overlooking the consequences of these rules is not an accident. Rather, it results from a longstanding hesitation around surveilling the evolutions in market structures, including those that facilitate the flow of payments, in order to understand systemic risks.

In conventional understandings, scholars and regulators conceptualize the payments system through the transfer of funds and exchange of information. I, however, argue that the contemporary payment system additionally depends on the flow of risk. I introduce the perspective of corporate treasurers, for whom managing the risks of wholesale, cross-country payments precede funding. As cash-rich institutions, multinational corporations (MNCs) are concerned not so much with access to funding but with obstacles posed by foreign exchange fluctuations, cash flows, and supply chain disruptions. To account for these risks, treasurers integrate a hedging strategy into their payments process.

For regulators, this analysis contains an important upshot: stability in the global payments system depends on the health of derivative markets. Beginning with the practices which constitute market microstructure thus highlights the indirect implications of regulatory measures, demonstrating the linkages between ostensibly separate spheres of market behavior.

The class view of payment as a system of daily credit management

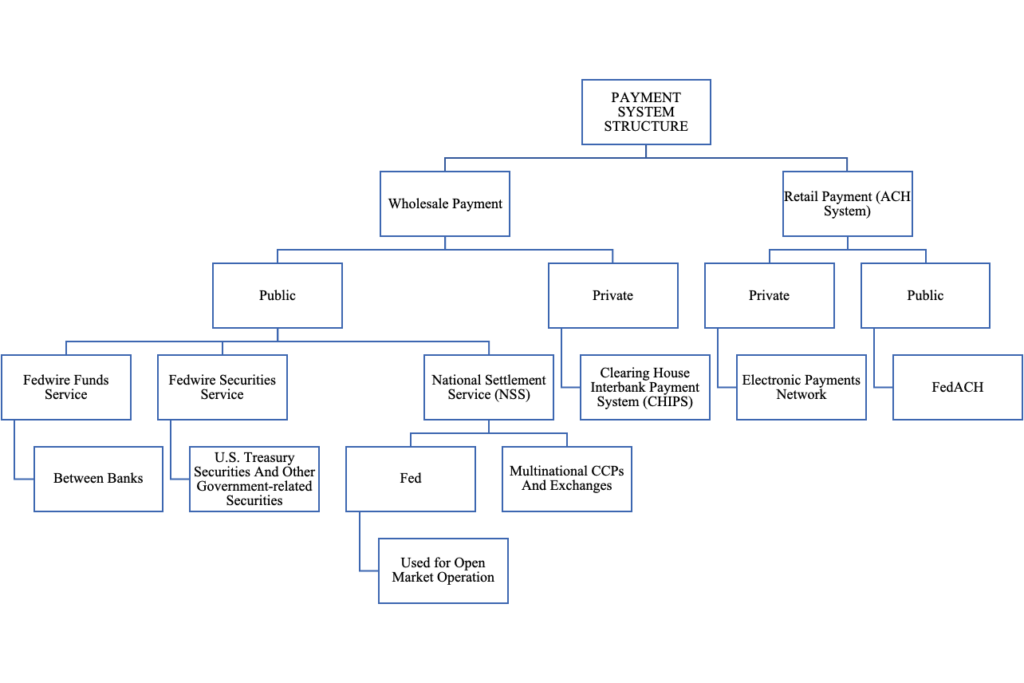

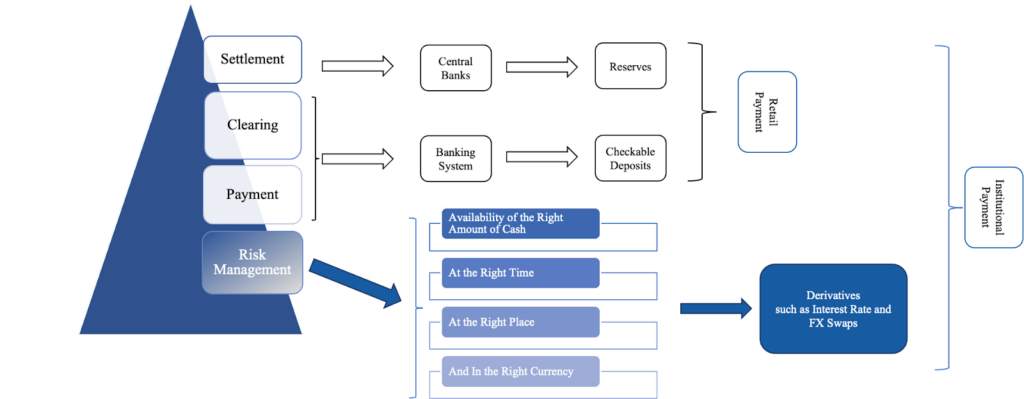

Two understandings of the global payments system prevail. Among regulators, the payments system is primarily understood through the lens of clearing and flow of information. It is divided into three stages: payment, clearing, and settlement. At each of these stages, transactions depend on IOUs (i.e., liabilities) issued by various entities. Payments between actors within the real economy are made through bank deposits. These deposits are cleared via information sharing between major financial institutions. And finally, net payments are settled using reserves.

Transactions within the flow of payment thus illustrate the hierarchy of money underpinning our contemporary financial system. Small and medium-sized banks issue deposits, automated teller machines (ATMs), and electronic fund transfers. Non-banks provide credit and debit card networks. These claims are cleared using private intermediaries who route information among financial institutions. And finally, they are settled through central bank reserve issuance.

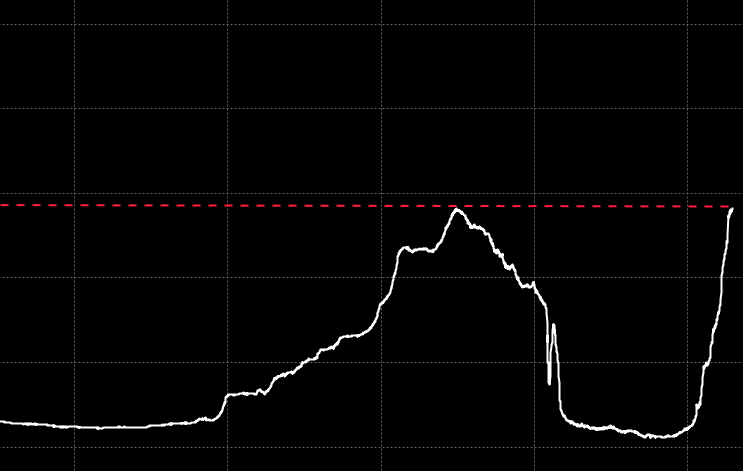

Among scholars, the payment system is often conceptualized as an intraday credit management system. In this framework, central banks manage liquidity based on an intraday credit. With this service, banks and non-banks temporarily expand their balance sheets to increase the system-wide credit level. This “operational intervention” or “payment coordination” happens when banks and non-banks supply the minimum liquidity required to settle all payments by critical intraday deadlines. When time-critical payments experience a delay or are at risk of being missed, these institutions intervene (by pledging more collateral, providing more credit, or altering payment timings). This expanded purchasing power enables clients to meet their critical intraday payment deadlines without depending on settlements from central banks. When such payment coordination or credit intervention does not occur, it could trigger systemic missed payments or outright central bank intervention.

But only a fraction of intraday credit expansion is ultimately funded by reserves. Liquidity-saving mechanisms (LSM) complement the real-time gross settlement systems (RTGS) by allowing banks to delay payment or place payments in a “queue” with specific rules for release (typically once the bank has sufficient reserves in its account or once the payment can be offset by other transactions). LSM significantly reduces the amount of reserves compared to the total value of transactions in the real economy and financial system.

The dynamics of intraday credit creation and contraction transform the payment system into a private-public network of credit management. During the day, newly created means of payment become indistinguishable from reserves. But once markets close, central bank liabilities become the only acceptable money to fund outstanding payments. The majority of the private purchasing power the banks create during the day disappears.

The two different conceptualizations of the payment system bear different implications for system stability. Among regulators, the primary concerns are the lack of transparency and insufficient infrastructure for information sharing. By contrast, scholars foresee systemic disruptions resulting from a lack of intraday liquidity for large-value real-time gross payment. Each of these views leads to different solutions to ensure stability: regulators push for standardization and central clearing of the products while central banks direct their member banks to hold extra overnight reserves on their accounts to ensure financial stability.

The modern view of the payment system as a hybridity of risk and credit management

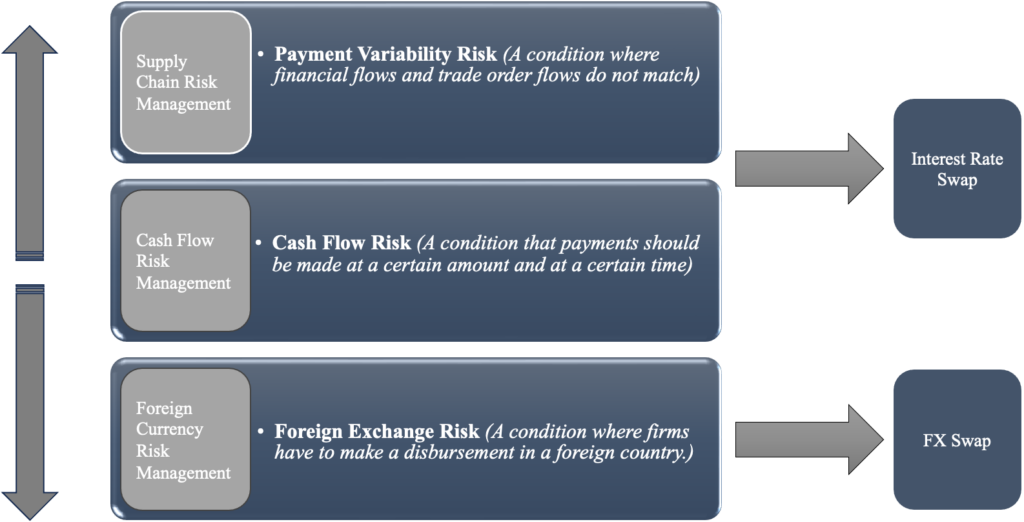

Things look different from the perspective of actors in the market. Analyzing the behavior of corporate treasurers actually responsible for making payments reveals a parallel infrastructure underpinning payment flows: risk management. In order for a retail agent to make payments, corporate treasurers must manage a spectrum of payment-related risks, including supply chain, cash flow, and foreign exchange risks. In other words, for most corporate treasurers, the payment system has four, rather than three, stages: risk management, payment, clearance, and settlement.

Even when institutions have sufficient means of payment, certain risks might still prevent them from paying on time, at the right amount, and in the correct currency. First, most transactions by multinational corporations happen in foreign countries and through foreign currencies. These companies therefore must manage risks arising from control over foreign-located funds, governmental restrictions on the cross-country movement of funds, and financial market regulations. Foreign exchange risk, which captures this category of exposures, could imperil their ability to pay.

A US multinational firm with cash inflows in Euros, for example, bears the risk that the latter will move adversely to the firm’s exposure in that currency: cash inflows are exposed to the depreciation of the Euro relative to the US dollar, while outflows are exposed to an appreciation of the Euro relative to the U.S. dollar. To deal with this risk, treasurers hedge their exposures using derivative instruments like foreign exchange swaps. These derivatives ensure the company’s ability to pay in the future by fixing the price of foreign currencies. For corporates handling charges in different countries, access to foreign exchange hedging instruments is the de-facto first step of payments.

Global corporations are also vulnerable to fluctuations in the global supply chain. Payment variability risks arise from a mismatch between products, information, and money—if the prices of vital inputs change significantly, or a container ship traffic jam affects production costs, for example. In these instances, firms must make similar or even higher payments with a lower output. If the firm is an essential player in the global supply chain, it could reduce its revenue, minimize trades with its partners, enter a cycle of missed payments, and ultimately break the supply chain. Corporate treasurers manage supply chain risks using derivative instruments like forward and futures contracts. These hedging products help corporations maintain production even when the input prices change significantly.1

Finally, corporations are concerned about their ability to pay an exact amount of cash at a precise time. This cash flow mismatch risk may stem from an anticipated loss due to defective products or other operational mishaps. It is dealt with using the “cash flow hedge.” Through risk neutralization, a company can mitigate the outcome of an expected loss from an identified risk by reducing the likelihood of it occurring or reducing the severity of the loss should the identified risk be realized. Alternatively, the firm can “transfer risks” to a third party. For instance, the corporation may enter into a contract with a counterparty willing to take on those risks. Otherwise, the firm may embed the risks into a structured financial product and sell the securities in the fixed-income market. In this case, the risks will be shifted to the bond investors willing to accept it. These transactions take place through derivatives and structured finance.

Using derivatives, corporate treasurers are thus able to mitigate potential disruptions to firms’ payment commitments. For these actors, payment is inseparable from risk management. Corporate treasurers administer institutional payments by forecasting transactions and managing a spectrum of payment risks. They use derivatives to ensure the risks do not materialize and payments go through. Credit and risk management, therefore, add a fundamental outer layer to the hierarchy of the payment system.

Hybridity as a pillar of financial stability

The payment system is a dynamic map of global cash flows facilitated by a network of private entities and central banks. The market microstructure lens reveals the countless linkages facilitating these payments. Notably, it points to the connection between risk management and the flow of payments, integrating derivative and funding markets into our understanding of how payments work.

The shift from LIBOR to SOFR imposes different sets of rules on dealers and bankers, with dealers likely to face a bigger regulatory burden than their bank counterparties in the funding market. Because the payment system links the business model of bankers and derivative dealers, such developments have the potential to impact the payments system as a whole—systemic risk in the payments system may arise out of diverging business models and financial incentives of key institutions. This approach goes beyond measuring a few designated systemically important institutions’ liquidity, capital, and leverage ratio. At the core, the stress shifts from the static measurement of the balance sheets to the dynamic changes in the business models that could affect essential functions in the ecosystem.

In today’s financial system, the secular rise of missed payments in the corporate world can be rooted in the pipelines facilitating both hedging and credit instruments. Such interpretations allow policymakers to capture the shifts and linkages in the complex financial ecosystem and design regulations that control market-based cycles rather than charge them postmortem.

To understand such hedges and their importance for the payments, let us assume a company that purchases plastic resin regularly during the regular production course. The fluctuations in the cost of plastic resin can change the production costs. As part of its risk management strategy, the company entered into resin forward hedging transactions constituting approximately 15 percent of its 2023 resin needs and 10 percent of its 2024 resin needs based on 2022 volumes. These contracts obligate the company to make or receive a monthly payment equal to the difference in the unit cost of resin per the contract and an industry index time of the contracted pounds of plastic resin. Such contracts are designated as hedges of a portion of the company’s forecasted purchases through 2024. They are effective in hedging the company’s exposure to changes in resin prices during this period.

↩

Filed Under