The energy transition is underway and the global North is putting up the cash. In our series, we have investigated questions about the international hierarchy of money, the distribution of economic power, and trade wars. Today, we turn to labor, which will determine whether the energy transition can develop a mass constituency—or whether it flounders as workers are left behind and rebel.

In this new political and economic context, a raft of questions are emerging. Can labor adapt to nascent green industries? Can new industrial policy investments reverse the erosion of wages for non-college-educated workers? Will unions be supported or further undercut as new sources of labor are developed? Will enough new skilled workers be trained to execute the transition, and in which countries will they work?

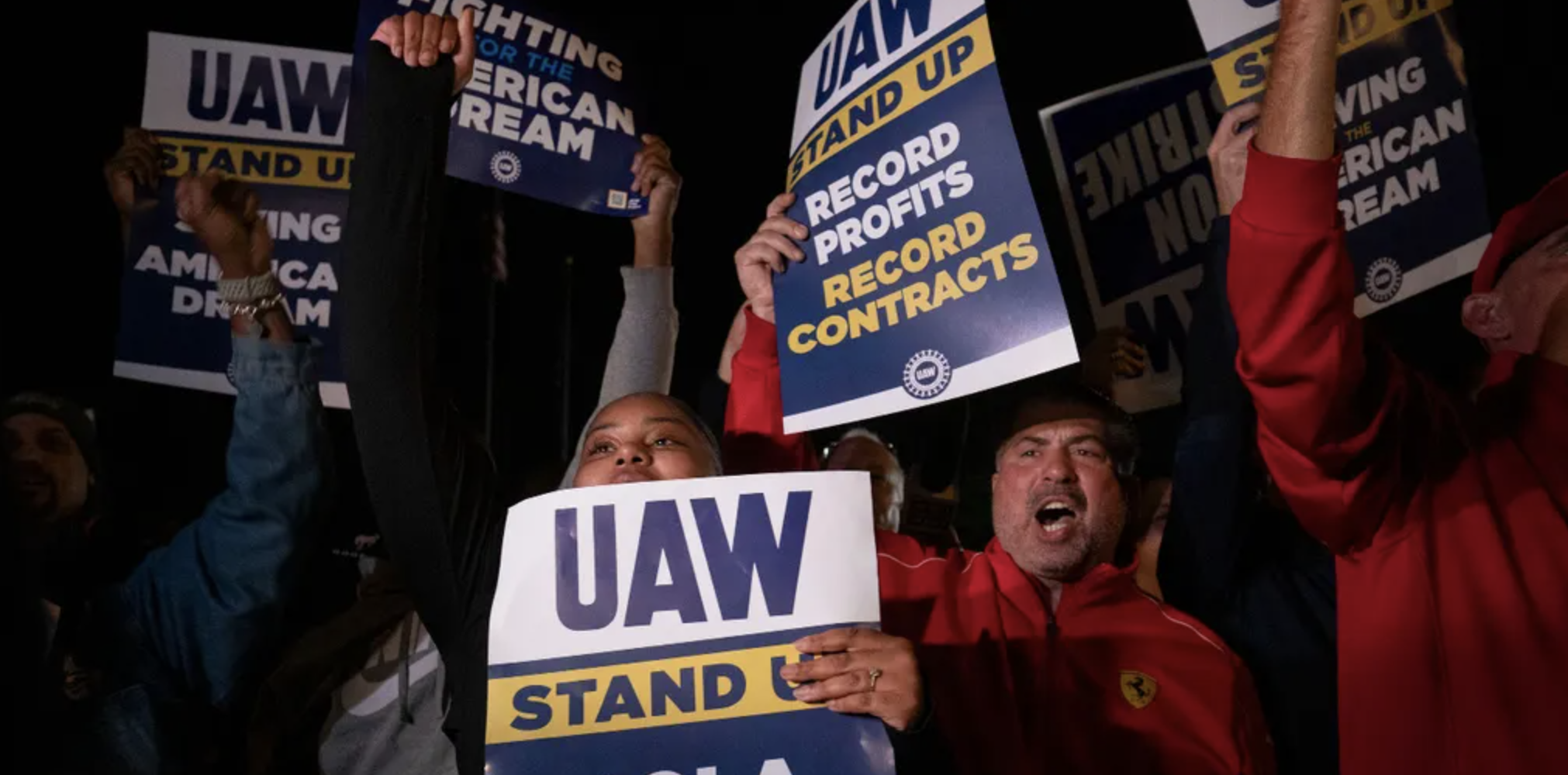

With manufacturing investment just beginning to tick up, and mining prospectors starting to stake their claims in rocky Nevada soil, it’s too soon to see the whole picture. But a searing discrepancy between North and South is evident. In the US, unions are asserting their demands amidst an upsurge in strikes. Union reform campaigns have given workers more militant leadership, and a tight labor market has given them greater leverage in the new energy economy.

In the global South, meanwhile, the energy transition is underway in a much slacker labor market, where precarity and informal contracts rule, and little in the way of a social safety net exists. Workforce shortages that constrain US producers positively cripple poorer countries’ efforts to move up the value chain. If both rich and developing countries have underinvested in industry that builds and trains needed human capital, the latter face tougher conditions for catching up in boom times.

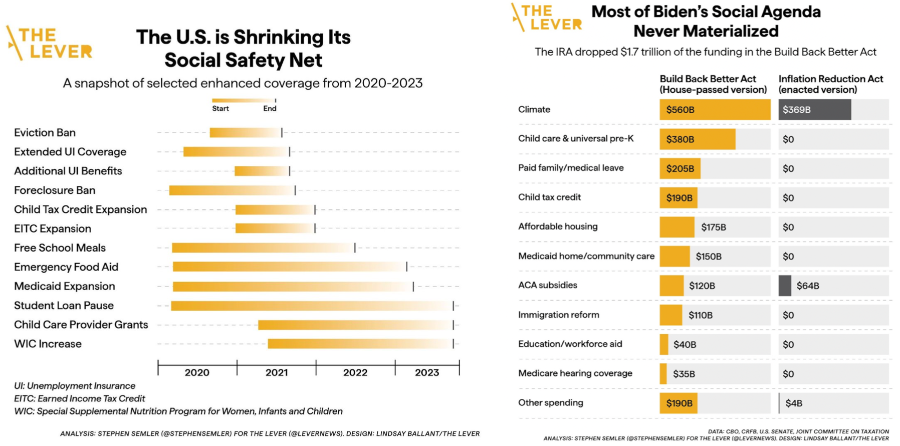

Ecologists say that the planetary crisis has deep roots in the contradictions of capitalism—a crisis in reproduction and production, a crisis not just of carbon, but of care. If that sounds abstract, consider Joe Manchin, the conservative Democratic Senator from the gas-rich state of West Virginia, who authored the Inflation Reduction Act. He slashed all social welfare, eldercare, and childcare funds from the House-passed Build Back Better Act, while boosting critical mineral extraction, fast tracking the construction of new pipelines, and providing incentives to oil and gas.

Strike weapon

Last month, for the first time in US history, a sitting president walked a picket line in solidarity with striking United Auto Workers at a GM plant in Detroit. If Reaganomics was framed by the GOP’s crushing of striking airport workers, Obamanomics by pressuring autoworkers to swallow wage cuts, Biden’s support of the UAW carries a new symbolism. Bidenomics has from the beginning sought to increase the bargaining power of workers in their conflict with capital over the national income.

Four out of five Americans support the UAW strike. As the union’s president Shawn Fain (yes, the US has its own IRA and Sinn Féin) has summarized, companies have raised prices on vehicles by 35 percent while raising wages by just 6 percent. CEO pay has gone up 40 percent. Biden has responded by appealing to workers: “You sacrificed a lot in 2008 when the auto companies went bankrupt; now that they are doing incredibly well, you should be doing well too.”

Since coming to power in 2021, Biden has repeatedly emphasized his intention to bridge the growing divide in the Democrats’ traditional voter base. Throughout the twentieth century, center-left parties around the world relied on coalitions of non-college-educated workers with those from the professional-managerial classes. In recent decades, that cross-cutting social coalition has broken down, as Thomas Piketty and others have documented, and working-class voters have abandoned social-democratic parties.

The Biden agenda seeks to bring working-class voters back into the fold. When Democrats retook Congress in 2021, they first focused on plugging some of the many holes in the welfare system. Expansions to social services were then paired with pro-labor provisions in bills in an effort to create jobs for those without college education and make it easier to unionize. The National Labor Relations Board was restaffed away from its anti-worker Trump membership. When anti-union Democrats tanked the Protecting the Right to Organize (PRO) Act in Congress, the administration resorted to executive action—federal contractor rules, NLRB penalizing anti-union employers—to lift wages.

According to a new report by University of Massachusetts and the Blue Green Alliance, 70 percent of jobs created by CHIPS/IRA/IIJA over the next decade will be for non-college-educated workers. And beyond the administration’s policy support for unions, Biden has just launched a Climate Civilian Corps, which will train and employ young people in nature restoration and disaster relief.

The macroeconomic policy has been to continue running a hot labor market with the Fed targeting full employment and risking inflation going above the 2 percent target. The result is that gaps between black and white unemployment rates, as well as for wage growth for those with and without college degrees, has narrowed. Low unemployment has in turn shifted power from employers to workers and boosted workplace militancy. This year, Teamsters, teachers, writers, and healthcare professionals have all fought successfully for better contracts.

A full employment economy and striking unions are all good news for the American labor movement long on the backfoot. But will these higher wages and benefits be will o’ the wisps or turn into something more permanent? Last Friday, UAW secured a historic win that will shape the future of EV jobs in North America: General Motors agreed to put its new battery factories under a master union contract.

Skill shortage

Last month, at the foot of the Rocky Mountains, mining experts gathered at Colorado School of Mines to plot the resurfacing of an American industry once considered virtually extinct. At a symposium on critical minerals, national security officials and energy executives mingled with scientists to survey the investment landscape for copper, lithium, and metals seeing white-hot spikes in demand.

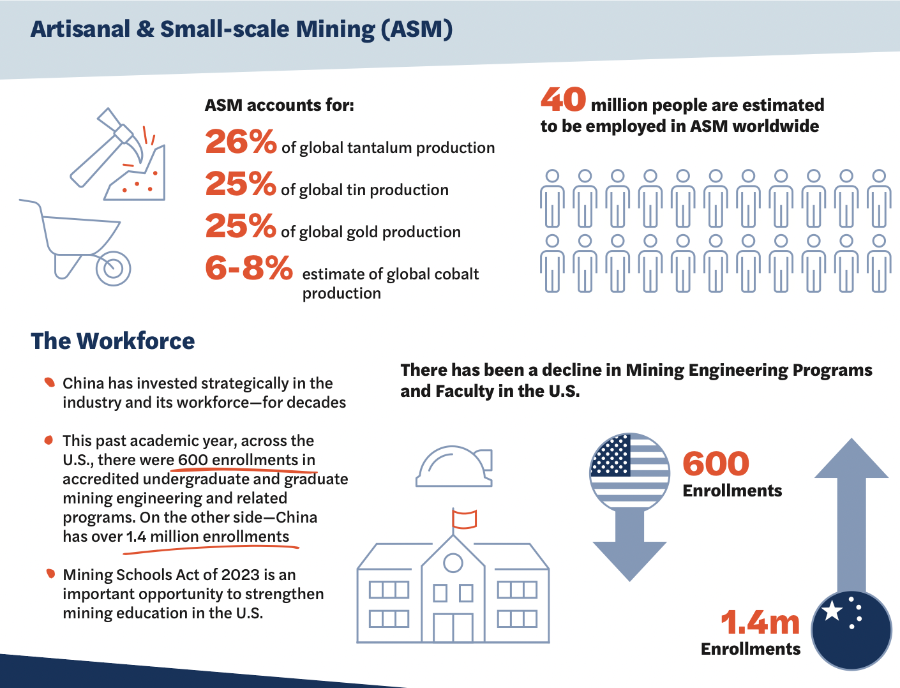

While public discussion has agonized about the availability of minerals, investors have other concerns. The physical supply of minerals can be secured, they say, but ESG risks are a political minefield and there is a persistent shortage of skilled workers to extract and refine them. Long-term underinvestment has eroded mining workforce capacity, and much of the institutional knowledge in mining is held by an aging workforce, or has otherwise been lost entirely thanks to offshoring.

Now Manchin has suddenly realized that throwing money at industry is not going to solve the spectacular shortage of skilled workers. At the Colorado symposium, he argued for the need to make fresh recruits to the mining industry, promoting his new bill on the topic in the process. “Legislative support such as grants for mining schools,” he said, were “vital” in the context of “hundreds of thousands of retiring workers.”

If there are shortages of skilled workers in the US, the situation is far more extreme in countries in the global South. Small scale mining—so-called artisanal mines—employ the vast majority of mining workers, more than 40 million people worldwide. How can they be supported in the energy transition?

Skilled mining labor that supports large-scale and capital-intensive mines is transnational. Workers in one country are often attracted to other countries where wages and benefits are better. One is more likely to find South African mining engineers working in Australia or Canada than at home. Labor migration might be a solution to skilled worker shortages but it is in conflict with other objectives.

Gone are the days when mining majors could open a few primary schools, drill a few wells, and bribe officials to retain mining rights. As Western-based multinationals return to African and Latin American countries to obtain more drilling rights, they are finding that some countries no longer intend to be plundered for raw materials at basement prices. The DRC has negotiated a higher royalty rate on Western and Chinese companies, and last week a domestically-owned company won a smelter to process cobalt and copper dug up by millions of Congolese artisanal miners.

To obtain a social license to operate extractive industries, both national and local leaders trumpet job-creation. But jobs for whom? A conflictual dynamic plays out over and over again in many countries. A shortage of skilled workers domestically leads to use of foreign workers which means resentment and often violent conflict with local workers. Management and companies often frame such local workers’ protests as xenophobic. Industrial policy proponents in both advanced and developing economies are more committed to training and recruiting local workers.

Solidarity surge

While the interests and conditions of workers in the North and South may not necessarily converge, recent months have shown remarkable displays of solidarity. In Brazil, for example, workers sent messages of solidarity to American autoworkers. Autoworkers in Mexico are going further, refusing voluntary overtime in support of the US strike.

Solidarity campaigns from Brazil and Mexico to South Africa, Malaysia, and France are backing the UAW. “In Europe…our unions are facing the same problems of low wages and job insecurity,” the leader of a French teachers’ union said in a support video. On October 13, he added, European unions will call on the public to demonstrate to oppose austerity and for equal pay.

In a week when saltwater is creeping up the Mississippi River and another shoddily designed Himalayan dam has left dozens dead, it is heartening—and surprising—to see the expression of so much cross-border worker cooperation.

Not to say that coordination among a global green workforce will be easy. Earlier this year, Germany and India signed a memorandum of understanding, agreeing to increase green skilled migration, but such commitments remain fledgling. But those who write the “decisive events of our time,” as Pope Francis reminded us, are the “doctors, nurses, supermarket employees, cleaners, caregivers, providers of transport, law and order forces, volunteers, priests, religious men and women and so very many others who have understood that no one reaches salvation by themselves.”

Filed Under