This is the twelfth edition of The Polycrisis newsletter, written by Kate Mackenzie and Tim Sahay. Subscribe here to get it in your inbox.

The maiden flight of a new cargo route between Shenzhen and São Paulo took off on Monday as European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen and France’s Emmanuel Macron prepared to travel to Beijing. US Vice President Kamala Harris has just been in Africa, attempting to avoid talking about China. Next week, Brazil’s President Lula and an entourage of hundreds of local business people will travel to the Chinese capital with plans to sign at least twenty bilateral agreements.

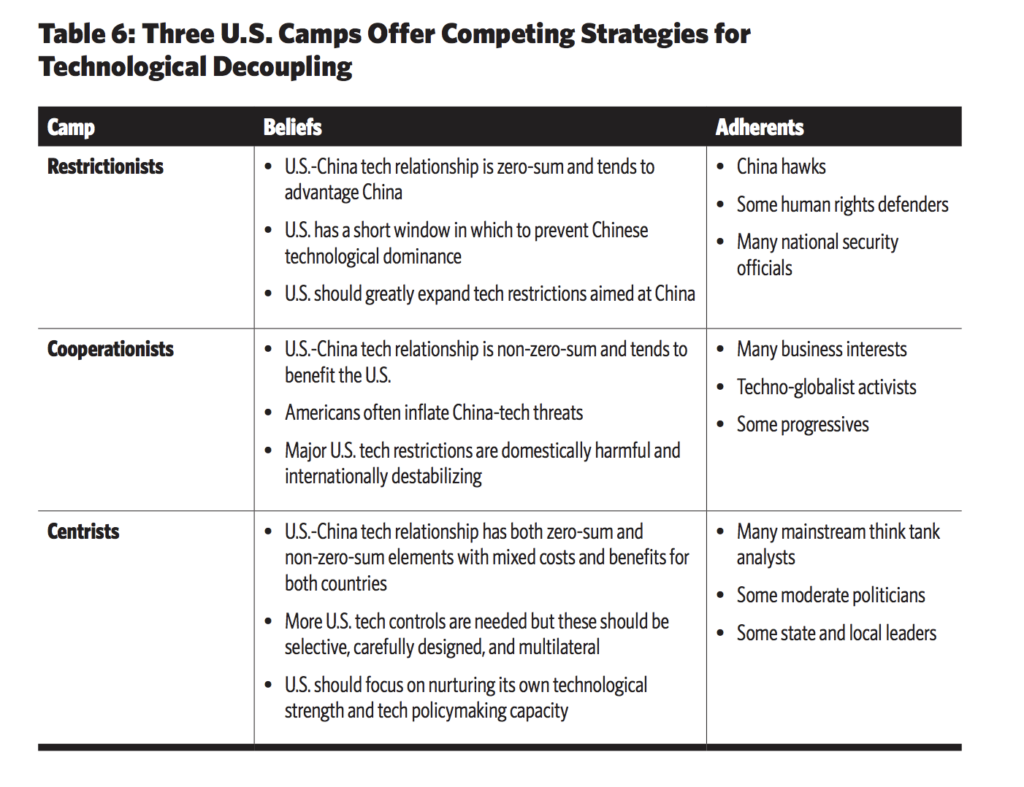

Each of these diplomatic journeys are the result of growing preoccupations with industrial policy, fragmentation, and the energy transition thanks to tensions around China and Russia. Trade flows, supply chains, and entire industries are rapidly being reorganized. Free trade led by “cooperative factions” in key countries has given way to “friend-shoring” led by “restrictionist” factions, largely on grounds of national security. New policies on export controls, visa bans, investment blocks, and sanctions are redirecting the flow of goods and people. US Allies, adversaries, and firms face hard questions: Who can invest in your country? Who can you sell to? What can and can’t you sell? Which countries do you risk arrest for trading with?

Table from US-China Technological “decoupling”: a strategy and policy framework by Jon Bateman (Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2022).

Europe, having dramatically cut its reliance on Russian gas within the space of months, still faces challenges around its own energy security and its place in this latest industrial revolution.

The EU was alarmed by the IRA’s strict Made in America requirements on the components, parts, and assembly required to qualify for the $7,500 consumer tax credit on each electric vehicle. Tense negotiations over the last six months resulted in the announcement of a far reaching EU-US agreement. The Biden administration has overruled a protectionist Congress and allowed the EU, Japan, and South Korea to source processed minerals from home, assemble them into batteries, and then get reduced consumer subsidies when selling them into the American market. Senator Joe Manchin, however, is not happy with the US Treasury battery rules. “American tax dollars should not be used to support manufacturing jobs overseas,” he said. “It is a pathetic excuse to spend more tax payer dollars as quickly as possible and further cedes control to the Chinese Communist Party in the process.”

Europe’s own stance towards China is more fragmented still. Cooperative factions in the bloc remain more powerful than restrictionist factions. “Our relationship with China is far too important to be put at risk by failing to clearly set the terms of a healthy engagement…I believe it is neither viable—nor in Europe’s interest—to decouple from China,” said European Commission President von der Leyen in her agenda-setting speech last week.

The European Commission’s attempts to align with restrictionist American interests are not supported by member states like Germany or France, whose leaders Olaf Scholz and Emmanuel Macron are opposed to national champion firms like Volkswagen, BASF, Alstom, and Airbus losing their China market. Von der Leyen wants member states to “derisk,” not decouple, from China, by controlling outbound investment for dual-use technologies like artificial intelligence or biotech that can be put to civilian and military purposes. On green technology, the EU has ambitious targets for local production (to substitute current sourcing from China) in its new Net Zero Industry Act. In contrast to the IRA, however, these targets remain unfunded.

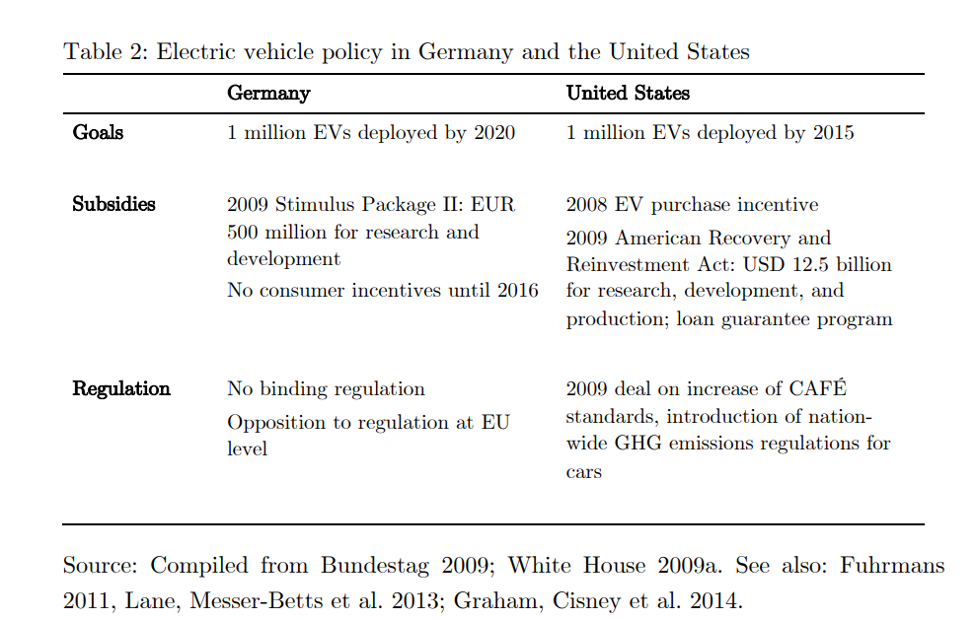

Car manufacturing will have an outsize role in this pivotal juncture, perhaps even more so than the petrostates we covered in our last newsletter. In the US, the administration is walking a line between Congressional desires to promote US jobs and keeping big car manufacturing allies on board with its foreign policy goal of containing China.

Fresh from forcing Germany’s coalition government to exempt synthetic e-fuels in the EU ban on internal combustion engines by 2035, the German car industry has strong views on relations with China. The powerful sector is enmeshed with China’s domestic automotive landscape through dozens of local plants and joint ventures. Besides, the country is the biggest source of profit for Mercedes, VW, and BMW. Can the restrictionists win against cooperationists? In 2022, Germany’s Ifo Institute surveyed roughly 4,000 national firms about their import relationships with China. Four out of five firms wanted to reduce their imports of Chinese inputs and buy more inputs from European countries.

German automakers might have other problems in China. EV sales there are growing rapidly, while foreign car brand sales are falling. Neither of these bode well for Germany, which has consistently dragged its feet on electrification.

Table from Jonas Meckling & Jonas Nahm (2018), “When do states disrupt industries?” Electric cars and the politics of innovation,” Review of International Political Economy, 25:4, 505-529.

Developing countries push back

For their part, countries in the global South are cautious about getting caught between bigger powers. They point to the escalating Cold War that is breaking down the free movement of goods, technology, and people. Shortages of food, energy, money, and technology have all intensified because of Covid-19 and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Can they risk a full blown war between the US and China? Can they risk losing export markets where they earn precious hard currency during a worsening global debt crisis? The IMF’s latest report on fragmentation estimates that 2 percent of world economic output could be knocked out, with losses rising to 7 percent for developing countries. The new Cold War is going to hurt trade, migration, capital flows, and technology diffusion. Losing 7 percent of a country’s GDP is devastating. As the proverb goes, when elephants fight, it is the grass that gets trampled.

New protectionist (“Buy American”/“Buy European”) industrial policy in the rich world is in tension with the agenda of developmentalist states in Asia. Developing countries are seizing the new policy space that has opened up to pass non-WTO compliant policies like local content requirements and export bans. Indonesia’s president Jokowi has banned export of the country’s raw nickel. His government is demanding that Indonesian minerals remain onshore for domestic processing and that foreign firms instead transfer technology like high pressure acid leach there to make battery-grade nickel. The policy has helped secure Chinese investment in Indonesian processing and even battery capability. The Chinese company CATL, South Korean LG, and American Ford and Tesla have all set up joint ventures in Indonesia with the state-owned mining and battery giants.

In Brazil, South–South cooperation has long featured in Lula’s foreign-policy program. He has signaled a policy of strategic non-alignment, rejecting any new Cold War between the US and China, pledging to “have relations with everyone.” Former president Dilma Rousseff has relocated to Shanghai to lead the New Development Bank (NDB), also known as the BRICS bank, which she was involved in setting up in 2014. Since Bolsonaro’s defeat, diplomatic and trade relations between Beijing and Brasilia have been recovering. China, which just one year ago purchased none of Brazil’s corn, is now its biggest customer, enabling Beijing to drop corn imports from the US. Brazilian beef, too, is now being exported to China, which has been the biggest market for Brazilian soy since 2018, after Trump’s tariff war.

Again, though, it is the energy transition and electrification that are creating entirely new paths in geopolitics. As EV demand soars, Brazil is involved in talks with Argentina, Chile, and Bolivia on a “lithium OPEC”—an attempt to replicate perhaps the most successful South-South solidarity exercise in modern history.

Western-China relations are at their lowest point in decades and spiraling further. US Secretary of State Blinken was forced to cancel his visit to Beijing by the spy balloon fiasco. Cooperationists are pushing back in the US too. Free traders, ex-Generals, ex-Intelligence analysts, civil society groups, scientists, and even Bernie Sanders have all argued for detente. Meanwhile, the G7 will be negotiating their economic security counter measures against China at Hiroshima in May. But what do national security driven “blocs” of globalization look like? If we are lucky, perhaps they look like an improvement on the patchwork that gave us vaccine apartheid. If we are unlucky, it looks like a mushroom cloud.

Filed Under