Ecuador’s prominence in the transnational network of organized crime is a relatively recent phenomenon. Although the country has supplied chemical inputs for cocaine production in Colombia since the 1990s, there were few spikes in violence or power struggles between criminal organizations fighting over control and access to drug trafficking routes. In early 2024, however, Ecuador captured global attention when an organized criminal group (OCG) took over national TV channel TC Television, holding staff hostage in Guayaquil. Violence escalated dramatically the year prior, leading Ecuador to be classified as the most violent country in Latin America.

How did Ecuador transform into a battleground between local criminal groups? The most compelling explanation examines Ecuador’s strategic role in the logistics chain of drug trafficking. In just a few years, the Andean country has become a highway for the transportation of cocaine to the United States and Europe, making it a crucial zone for transnational organized crime.1

The rise of cocaine trafficking in Ecuador can be attributed to the influence of international OCGs, disputes among local OCGs, and the importance of the logistics and value chains for the globally lucrative cocaine business. The risk level of operations, the distance between production centers, and the various intermediaries involved in transporting cocaine to the global North influence both the profitability of cocaine production—as well as the resultant violence within Ecuador.

How does the price of a kilogram of cocaine, with an initial production value of $1,500 in Colombia, reach $20,000 in the United States? Confronting control strategies implemented by Colombia and the United States, criminal groups have been displaced toward the border regions, with an increase in illicit coca leaf cultivation and cocaine production in Ecuadorian territory. The Ecuador-Colombia border has become an epicenter of drug trafficking worldwide, with Ecuador generating approximately $300 million in revenue in 2019, in addition to the revenue derived from drug trafficking logistics, estimated at around $150 million in 2022 for the country’s OCGs.

While these numbers are relatively modest compared to the Colombian context, the flow of approximately 500 tons of cocaine per year to Ecuador—alongside still incipient but rising cocaine production—has incited conflicts over territorial control and institutional corruption. This scenario of war and criminal anarchy has left over 15,000 dead in three years. In response, Ecuadorian President Daniel Noboa has embarked on a desperate mission—declaring an “internal armed conflict” to combat criminal groups. Twenty-four years after the launch of Plan Colombia, Ecuador is following a similar path, with the government aiming to increase the military’s arsenal of weaponry in the state’s war on drugs.

Structural changes

To understand Ecuador’s rise in the drug trafficking value chain, we must look to two crucial moments in history: 2000 and 2016. The former marked the start of Plan Colombia, the Colombian government’s main strategy to combat drug trafficking. Supported financially and militarily by the US, the policy strengthened Colombia’s military and police in order to destroy illicit crops and target cocaine production. Part of the US “war on drugs,” the policy also increased maritime interdiction through the Southern Command of the Caribbean Sea to intercept cocaine transport. By 2016, upwards of $141 billion had been invested into Plan Colombia, with $10 billion provided directly from the US.

The strategy led to the borderization of illicit crops, which spurred interest in new border networks in the supply of chemical precursors, as well as in the consolidation of logistics networks for the transportation of cocaine to Central America and the United States. Although there was a reduction in cocaine flows in the Caribbean, drug trafficking organizations shifted their logistics networks toward the Pacific Ocean. In response to these efforts, Mexican criminal organizations assumed a more prominent leadership role in the drug trafficking business. Due to the “balloon effect” generated by maritime controls in the Caribbean, the Sinaloa Cartel saw a lucrative opportunity to establish a cocaine trafficking logistics network through the Pacific Ocean. In 2006, the International Narcotics Control Board (INCB) warned that the Pacific route had become more relevant for the drug trade, with Ecuador’s Galápagos Islands serving as a landing for vessels carrying cocaine to Central America and Mexico to evade maritime controls and refuel. 2

As a result, the Sinaloa Cartel strengthened its presence in Ecuador. The organization had operated in the Andean country since 2003, initially through emissaries whose objective was to coordinate the transportation of cocaine from production enclaves in Colombia to Central America and Mexico. Since then, the organization has established a complex logistics network in Ecuador responsible for mobilizing cocaine from the Colombia-Ecuador border to international markets, involving former Ecuadorian military personnel and a network of businesses and asset laundering facilitated through links and intermediaries of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC).

Faced with changes in drug trafficking routes in the region, the Sinaloa Cartel’s Ecuadorian subsidiary networks sought to embed itself in cocaine trafficking between 2010 and 2016. During this period, Ecuador’s OCGs perfected their logistics for cocaine transportation through the Pacific Ocean—these criminal organizations centered on the transportation and storage of cocaine. The Galápagos Islands, along with other supply and transfer points for cocaine such as Cocos Island in Costa Rica, became strategic locations to establish storage and transportation points for cocaine through loaded boats in open waters.

However, the balance of power of organized crime in Ecuador shifted in 2016, following the Colombia-FARC peace accords. Cocaine production began an aggressive decentralization process that particularly affected the Ecuador-Colombia border region The departure of FARC opened up space for the entry of new actors like Albanian, Italian, and Mexican mafias, who experimented with new techniques and supply chains that involved Ecuador. 3.

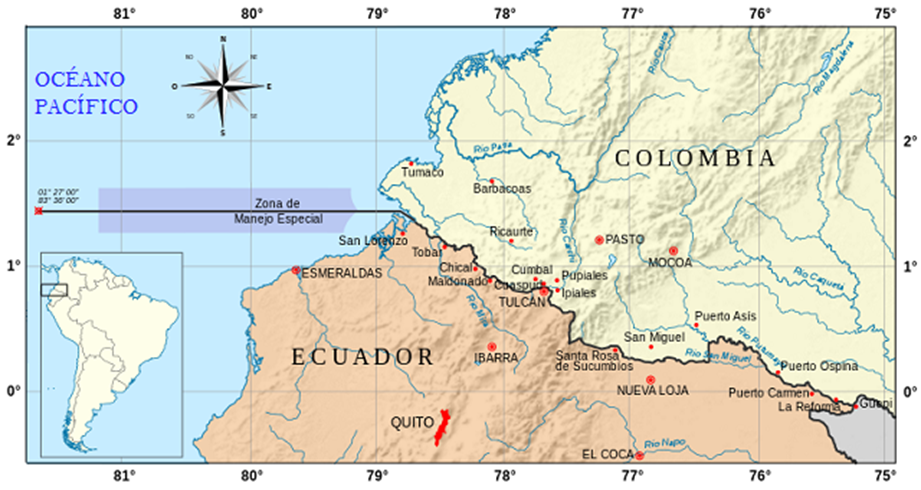

Figure 1: Border between Ecuador and Colombia

Decentralization coincided with the arrest and extradition of “El Chapo” Guzmán—the leader of the Sinaloa Cartel—to the United States, intensifying organized crime in Ecuador. The extradition resulted in a loss of power and legitimacy and created an opening for the Jalisco New Generation Cartel (CJNG). The CJNG, which began operations in Ecuador in 2018, aimed to mobilize shipments acquired from Colombian FARC dissidents through Ecuador to Central America and Mexico. To achieve this, the organization hired Ecuadorian logistical networks for cocaine transportation. One of the CJNG’s objectives in Ecuador was to weaken the most powerful criminal organization in the country, “Los Choneros,” which since 2003 was in a strategic alliance with Sinaloa. This alliance granted the Choneros significant power and a criminal monopoly in the country, but, with the weakening of Sinaloa, the CJNG began to finance their rivals. The CJNG quickly caught the interest of the Choneros due to structural changes in the cocaine business in southern Colombia. 4 The relationship between the cocaine economy and the power structure of the business led to the fragmentation of the Choneros organization by the end of 2019. What resulted was fierce competition among local criminal networks to control cocaine transportation.

Comprising three criminal groups—Tiguerones, Lobos, Chone Killers, and Lagartos—and financed by the CJNG, a new criminal structure, the “New Generation Alliance,” soon emerged. On the other hand, groups loyal to the Choneros, led by the new leader of the organization “Fito,” and supported by Sinaloa, remained. Within this landscape, Balkan mafias have surfaced as a source of financing for the highest bidder, generating even more aggressive competition among local criminal networks.

These changes in the local criminal structure, alongside international participation, have formed a kind of criminal anarchy in Ecuador. Alliances and disputes rise and wane amid bids to control drug trafficking routes and storage centers in the country. By the end of 2023, Ecuador’s high homicide rates led it to be classified as the most violent nation in Latin America. 5

The global cocaine chain

The economy of drug trafficking has undergone significant structural changes in recent decades. The managerial “cartel” model, where a few mafia structures control production, trafficking, and sale of illicit drugs in consumer markets, no longer prevails. In line with the process of economic globalization, criminal groups have adapted their business environment through an innovation strategy in drug trafficking, including the decentralization and specialization of various activities related to this lucrative illegal industry.

This evolution has transformed the economy of drug trafficking from a model dominated by large drug cartels to one where numerous criminal actors participate and specialize in each link of the chain. In the context of globalization, these groups have adopted practices similar to those in formal international trade, implementing a systemic value chain process aimed at reducing risks, increasing profits, and leveraging the specialization of each criminal organization operating in different territories.

In recent years, armed groups and OCGs from Colombia have specialized in cocaine production, while Mexican OCGs have specialized in logistical chains that transport various illicit drugs to sales networks for consumers. The groups dedicated to logistical activities constitute the most important and profitable link in the value chain, due to their ability to influence the selling price in the consumer market. Ecuador is situated within this dynamic of value chains.

Ecuador was historically considered a country with low levels of violence, a “peaceful island” compared to the serious security conflicts in Peru—where the coca leaf plays a significant role in the economy—and Colombia, which hosts persistent armed conflict. After 2019, the situation changed abruptly, with Ecuador’s proximity to the growth of illicit crops and cocaine production enclaves contributing to the rise in violence. According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), between 2015 and 2019 there was an alarming 76 percent increase in coca leaf crops in Colombia, rising from 96,000 to 169,000 hectares. 6 This increase was exacerbated by the FARC peace accords, which precipitated the rise of illicit crops in border areas. In 2016, 30 percent of crops in the border departments of Nariño and Putumayo were within 20 kilometers of the border, as depicted in the following image:

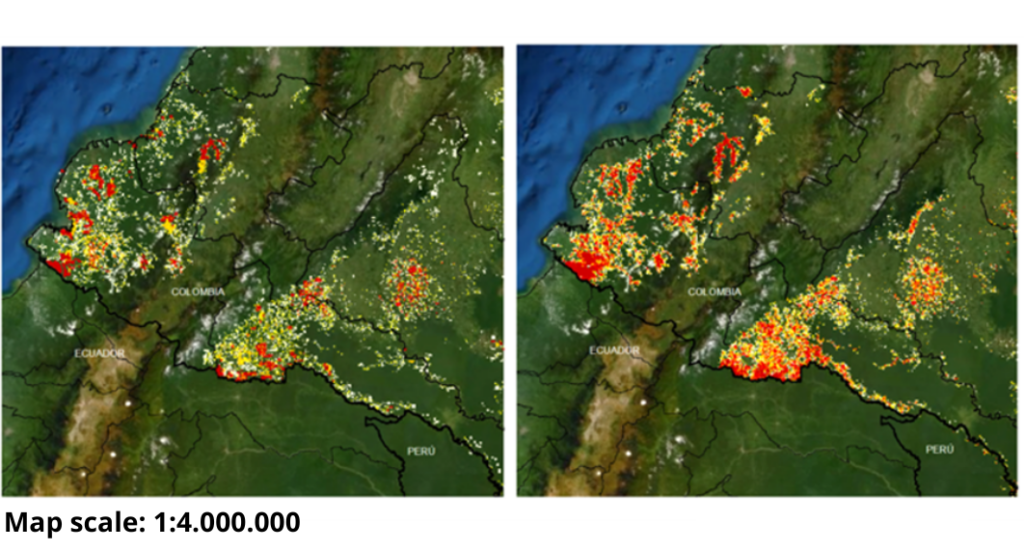

Figure 2: Concentration per hectare of illicit crops on the southern border of Colombia

By 2022, according to data provided by UNODC (2023), 47 percent of Colombia’s total cocaine production was concentrated in border departments with Ecuador. Furthermore, 50 percent of these crops were within a 10 kilometer radius of the border. These figures demonstrate a process of expansion or “borderization” of cocaine production centers into Ecuadorian territory, where criminal actors take advantage of the institutional weakness of states to exert control over borders. This is compounded by the state’s historical neglect of these regions—affected communities have few socioeconomic opportunities, making it easier to recruit cheap labor dedicated to the maintenance and harvesting of these crops.

Productive enclaves of cocaine in Ecuador

The cultivation and harvesting of the coca leaf shapes the nature of organized crime, given its status as a high-value, “plunderable” good, and its success or failure directly influencing the global cocaine market. Looking at the variation in cocaine hydrochloride production on the southern border of Colombia, the departments of Nariño and Putumayo, bordering Ecuador, reported an increase from around 20,000 hectares of coca leaf in 2010 to over 100,000 in 2022. This implies that by 2022, approximately 800 tons of cocaine were produced in Colombian territory destined for international markets.

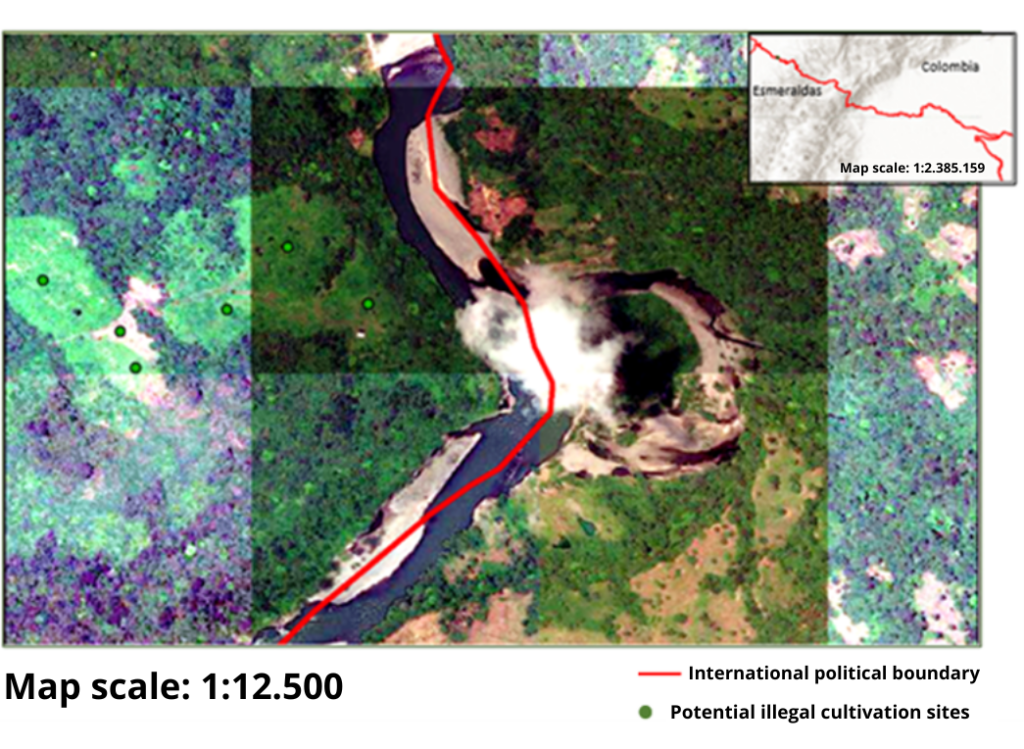

Although Ecuador was previously considered a country free of illicit crops, a 2020 study using satellite images identified 154 plots, representing approximately 700 hectares of illicit coca leaf cultivation at that time, in the provinces of Esmeraldas, Carchi, and Sucumbíos.7 Figure 3 shows the presence of illicit crops on the Colombia-Ecuador border, depicted on the left side.

Figure 3: Illicit coca leaf crops in Esmeraldas-Ecuador (2018)

Taking into consideration market costs related to the production yield of each hectare of fresh coca leaf, approximately 4,830 kilograms of cocaine could have been produced per harvest in the provinces of Esmeraldas, Carchi, and Sucumbíos. This is concerning considering that coca leaf crops can generate an approximate yield of eight harvests per year. Thus, using the production in the Ecuadorian northern border as a reference, approximately 38,640 kilograms of cocaine hydrochloride were produced in 2019 alone, representing approximate revenues of over $300 million for Ecuadorian GCOs.

Logistics

Situated between the world’s two main cocaine producers and using the US dollar, Ecuador has become a key point for cocaine trafficking worldwide. To transport cocaine from “productive enclaves” to Ecuadorian ports, OCGs use the extensive road network of the Amazon, the coast, and the Andean mountains, facilitating the movement of hundreds of kilograms of cocaine from the border to maritime ports in less than twelve hours. Additionally, they take advantage of international border crossings and approximately fifty informal crossings between Ecuador and Colombia, thus facilitating the transportation of substances and the supply of inputs for cocaine production.

Figure 4: Cocaine trafficking routes in Ecuador.

Intelligence reports from the Ecuadorian Anti-Narcotics Police estimate that between 70 to 80 percent of cocaine produced in the southern departments of Colombia enters through the northern Ecuadorian border.8 Analyzing this production-to-trafficking relationship in 2022, approximately 571 tons of cocaine hydrochloride entered Ecuador destined for Europe and the United States. Of these, only 32 percent are retained by the efforts of Ecuadorian control authorities, meaning that 68 percent of this production generated economic profitability for Ecuadorian criminal networks.

According to data obtained by the Ecuadorian National Police, each kilogram of cocaine yields Criminal Organizations an approximate profit ranging between $500 to $1,000. This represents revenues of over $150 million in Ecuador in 2022. Nevertheless, these figures do not include payments to third parties, bribes, or fees to Mexican or Albanian OCGs.

The absence of controls, profitability, and the significant presence of export ports make the city of Guayaquil in Ecuador the most important for cocaine trafficking to international markets. Amid conflicts between OCGs, 35 percent of the homicides nationwide have been concentrated in this port city. 9

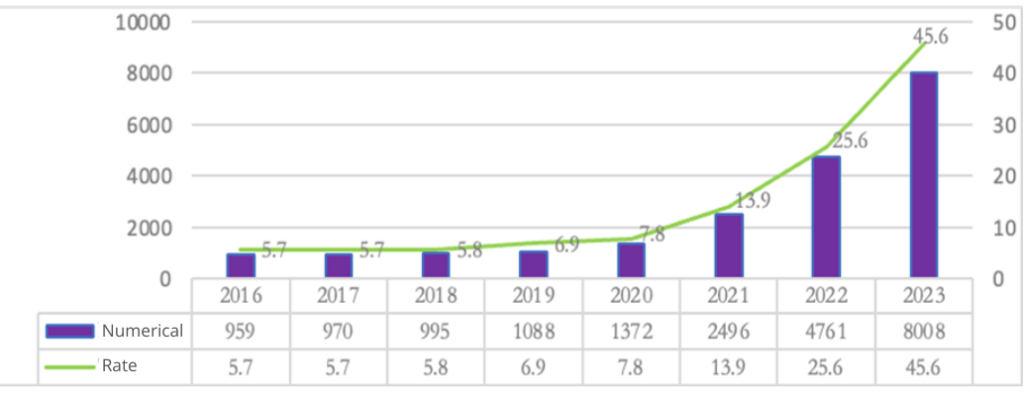

The profitability and interest in logistics prompted a substantial increase in violence in Ecuador. The country’s homicide rate increased from 5.7 in 2017 to 45.6 in 2023. 80 percent of violence in Ecuador is the product of disputes between those with criminal backgrounds. In a context of criminal fragmentation in Ecuador, homicide rates are significantly higher in the strategic corridors of drug circulation. Changes in the homicide rate in these corridors correspond to rivalries between drug trafficking organizations.

Figure 5: Homicides in Ecuador

Distribution and consumption in international markets

The Ecuador-Colombia border and the Mexico-United States border host the highest homicide rates in the world, “precisely because these points of entry are scarce, drug traffickers are prepared to fight tooth and nail to control them.” 10 Cases of tunnel construction and the Sinaloa Cartel’s expansion into Chicago and other US cities illustrate the need for OGCs to control large cocaine warehouses prior to their commercialization.

Once large packages reach distribution networks, kilograms of cocaine are divided into small portions to be sold in grams. The consumer constitutes the last link to complete the drug trafficking value chain and, at the same time, plays the most representative role as the economic catalyst of this phenomenon. This business is paid in cash, circulating its value back to large traffickers and producers.

According to the Global Cocaine Report (2019), the gram of cocaine in a producer country like Colombia has a value of less than $5, while it exceeds $215 in countries like Australia. Even the profit of those who sell the substance at retail (micro-trafficking) tends to be higher since they usually mix cocaine with cornstarch, talcum powder, lime, or fluorine to increase their profits. 11 The US accounts for 2.5 percent of global cocaine consumption; consumption and price determine the main destinations of drugs produced in the Andean region. 12

The Covid-19 pandemic saw the overproduction of cocaine, leading to an increase in cocaine consumption across the world. Europe and North America remained the largest consumers. According to the Global Cocaine Report (2023), “the estimated number of users worldwide has grown steadily over the past 15 years, driven in part by rising population levels but also by a gradual long-term increase in prevalence.” 13

As a supply and demand market, productive enclaves interpret their market and cater to production according to consumer preferences, which increasingly demand cocaine at lower prices, higher purity, and with a multitude of new actors willing to provide by any means necessary.

Ecuador’s path forward

With a dramatic four-year rise in violence, Ecuador shows that the absence of criminal activities in the past does not exempt a country from the influence of drug trafficking. The scenario prompts a profound evaluation of traditionally reactive security policies in Latin America, which center on substance interdiction actions and short-term policies. This approach has neglected fundamental aspects of prevention, such as border control, social cohesion, and, above all, the strengthening of financial intelligence units responsible for monitoring possible activities linked to money laundering and the growth of illicit economies.

The Ecuadorian case exemplifies how the drug trafficking economy has been shaped by internal and external factors of the value chain. Smaller groups enter conflicts in order to control logistics at the border regions, connecting production to trafficking, leading to the significant increase in violence rates seen after 2019. Although the transnational nature of drug trafficking is rhetorically recognized as a problem requiring greater coordination between hemispheric prosecutors and police institutions, in practice, there remains a high degree of distrust among states. This results in isolated actions employing a militarized strategy to promote interdiction and deterrence. Over two decades of militarization through the War on Drugs in Colombia and Mexico have not achieved the desired results. On the contrary, the militarized approach has contributed to the increase in the value and purity of cocaine in consumer markets.

Crop eradication policies have led transnational OCGs to specialize and adapt their business model through alliances and value chains that concentrate their activities in fragile institutional environments, such as border areas. At the Ecuador-Colombia border, strategies for interdicting productive enclaves have led to the “borderization” of drug trafficking, generating greater coordination between local and international criminal groups that have facilitated reducing their risks while managing to co-opt a greater number of officials in charge of their control.

Under President Daniel Noboa, Ecuador is pursuing a militarization and policing strategy that is destined to fail, relying on the reactionary approach and seeking little regional cooperation. Despite Noboa’s very publicized efforts to wage “war” on criminal actors, homicide rates have yet to see a dramatic decrease. Only cooperative approaches that understand the value chain will be able to address both the causes and consequences of drug trafficking. Such coordination requires strong regional political alliances, which may be difficult to forge given the ideological fragmentation on the continent. The fragmentation itself can in part be attributed to the dominant influence of the US, and divergent positions towards the War on Drugs across the region.

FootnotesJames Bargent, “Ecuador: autopista de la cocaína hacia Estados Unidos y Europa,” Insight Crime, October 30, 2019.

(International Narcotics Control Board, Report of the International Narcotics Control Board for 2006, New York: United Nations, 2006).

By Jonny Wrate, David Espino, Jody García, Angélica Medinilla, Enrique García, Víctor Méndez, Arthur Debruyne, Brecht Castel, Jand uanita Vélez, “Cocaína: todo a la vez en todas partes. Cómo la producción de la droga se extiende a Centroamérica y Europa,” Plan V, 2023)

Observatorio Ecuatoriano de Crimen Organizado. Informe de caracterización del crimen organizado en Ecuador, 2023.

Insight Crime, Balance de InSight Crime de los homicidios en 2023, 2024.).

Oficina de las Naciones Unidas contra la Droga y el Delito, Monitoreo de territorios afectados por cultivos ilícitos 2018, United Nations, 2019.

Rivera Rhon & Bravo Grijalva, Crimen organizado y cadenas de valor: el ascenso estratégico del Ecuador en la economía del narcotráfico, Revista de Estudios de Seguridad, 28 (2020).

OECO, “Evaluación situacional narcotráfico en Ecuador 2019-2022,” Policia Nacional, 2023).

OECO, “Evaluación situacional narcotráfico en Ecuador 2019-2022,” Policia Nacional, 2023).

Tom Wainwright, Narconomics: How to Run a Drug Cartel, New York: Library of Congress (2016): 83.

UNODC, World Drug Report 2019, United Nations, 2020.

Oficina de las Naciones Unidas contra la Droga y el Delito, Monitoreo de territorios afectados por cultivos ilícitos 2018, United Nations, 2019.

UNODC, Global report on Cocaine 2023—Local Dynamics, Global Challenges, United Nations Publications, 2023.

Filed Under