Protests led by farmers have been roiling Europe for months. In Belgium, Germany, Romania, the Netherlands, Poland, and France, farmers—armed with grievances ranging from subsidized Ukrainian grain imports to the EU-Mercosur trade deal and falling prices—have been taking to the streets, blocking traffic, and pelting the European parliament with eggs.

In the European halls of power, right-wing parties are taking note. In the Netherlands, populist and conservative parties have protested the ammonia tax imposed on the nation’s livestock. In Italy, figures in the ruling hard-right League and Brothers of Italy coalition have denounced EU decarbonization policies as hurting both consumers and industries. In France, Marine Le Pen, who ran for president as the National Rally candidate in the last election, is fighting against diesel taxes and for greater energy subsidies. The crystallization of a robust anti-climate coalition in the European Parliament is a real possibility after elections in June.

The farmers’ protests are a powerful reminder that the challenge to achieve “net zero” isn’t simply a technical one, but a political one. Unable to form or mobilize coalitions with working and middle classes, parties of the left have been locked out of power in much of the continent. Meanwhile, fossil-fuel interests have mobilized cross-class coalitions for militarized adaptation.

The socioeconomic risks of rebellion are not lost on incumbent governments in the global North and South. In the energy crisis of 2022–2023, European governments chose to cut fuel taxes and subsidize citizens’ energy bills on an enormous scale. Southern governments, for their part, continue to resist IMF’s consistent policy advice that they should stop supporting their populations with fossil-fuel, food, and agricultural subsidies.

Why is it so hard to stitch together a cross-class coalition for climate policy? One part of the answer may be that, for generations, electorates have been sold a political vision of modernity that is centered on the carbon economy. Legitimizing decarbonization with powerful electoral mandates to move sclerotic parliaments will require political leaders to persuade voters not just of its necessity, but also its desirability. It can’t just be a recipe for pain and sacrifice. The investment-based programs will have to differ from country to country. Worryingly, this is a task in which leaders in Europe and beyond are coming up drastically short.

In this interview, climate researcher Chris Shaw, author of The Two Degrees Dangerous Limit for Climate Change and most recently Liberalism and the Challenge of Climate Change, analyzes how our understanding of climate change has been shaped by liberalism’s limits, and why our dominant politics lacks answers for decarbonization.

An interview with Chris Shaw

Ts: What is it about liberalism that makes it particularly unsuited to dealing with the climate challenge?

CS: “There is no society,” as Margaret Thatcher put it. Hence the focus on individual change and market solutions in liberalism that guards against any systemic change.

Fossil energy provides individuals with a great deal of independence from other people. Fossil fuels give individuals the ability to make choices and buy items without relying on others. One doesn’t have to work as part of a group to hunt for food each day. Instead I can go on my own in my car down to the supermarket and buy what I want. That is a lot easier than having to work with my neighbors to build a different world. And one’s consumption can be used as proof of one’s status. So fossil fuel-enabled individualism in the West is seen as sacrosanct, as it enables freedom from constraints of social obligations.

It is very difficult to bring about climate action in a world that prioritizes individuals and in which we are so alienated from each other. Technology is intimately related to markets; one can define it as the practical application of science in the service of markets. I argue, much like the sociologist and philosopher Jacques Ellul, that technology changes culture, and the introduction of new technologies hinders the emergence of other ways of thinking and acting on climate change.

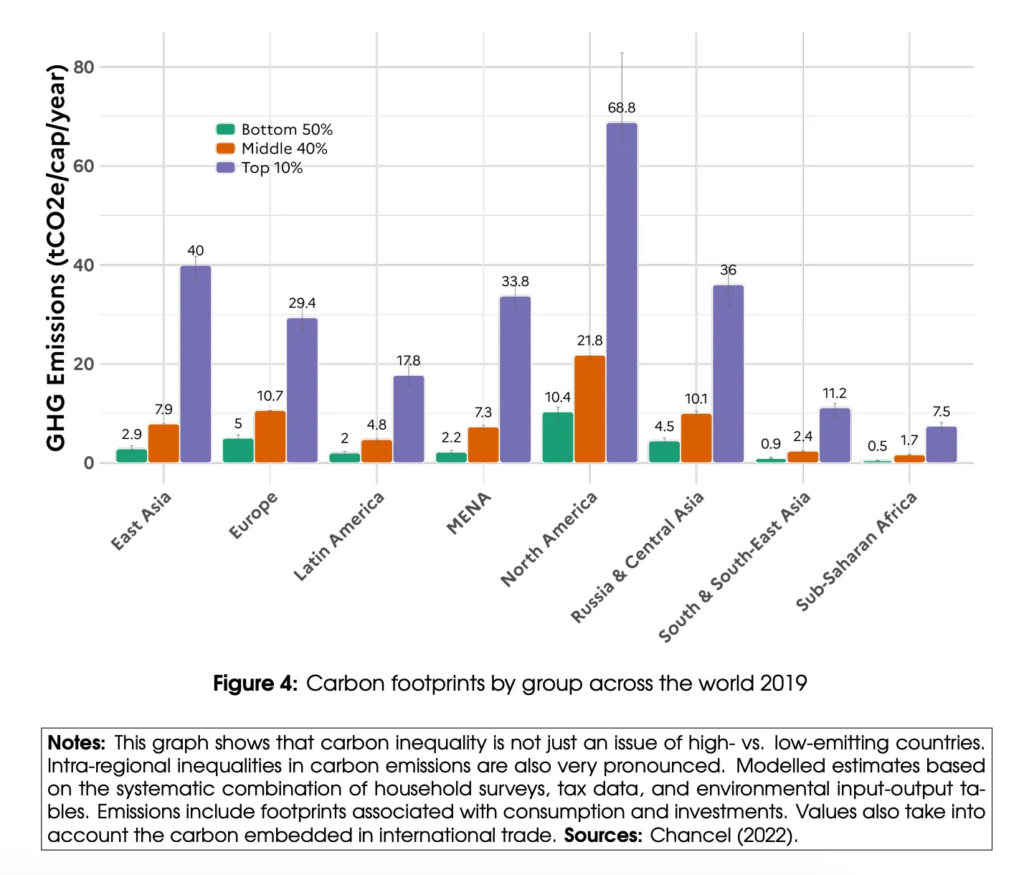

Ts: A lot of the language around climate policy is about “win-win” growth: everyone will be better off in the green transition, we’re told. It’s a universalizing discourse. But by now it is well understood that the impacts of climate change and the core responsibility of emissions are highly unequal. Why has this realization taken so long to emerge?

CS: Our scientific understanding of climate change emerged in the late-twentieth century, primarily in the institutions of the global North, which in turn promoted a globalized picture of climate change and denied the differentiated dimensions of the crisis. At its core was the idea that there is a single dangerous limit and that climate change is the same whoever and wherever you are. This is a conception that does not acknowledge climate change as a historical phenomenon. Instead, it’s one that is depoliticized, viewed purely on the basis of the science and targets.

Ts: In what ways have working-class perspectives been ignored in discussions about climate change? What does a positive vision of climate led by the working class look like?

CS: What is the most that a working-class person could hope for from a net-zero future? At present, in the vision being broadly promoted, it’s the same hard work, the same exploitation, but with a heat pump instead of a gas boiler. What do people fight and die for? They don’t fight and die for a fluorescent-lit strip mall. They don’t go and die to have central heating. Much of the discourse around net zero seeks to replicate all the comforts of middle-class life—for the middle class. That it needs the working class to come on board and do their bit to achieve it is one of many hypocrisies.

Four years ago, I went to a meeting in Brussels about climate justice. People there were shitting themselves because of the Yellow Vest protests in France. Their conclusion from the uprisings was that they needed to at least talk about climate in a way that met some of working-class concerns—but that’s all. Middle-class protests are fine—Fridays for Future, that’s great, because it’s aligned with the net-zero agenda. The “just transition” idea may have its roots in the labor movement, but here in Europe it’s become more of a liberal shibboleth, and I don’t hear working-class people talk about a just transition.

The vision presented is basically: “this world, but without the emissions.” But there is just no understanding of working class experience. It’s all, “Come on, care! Be concerned about this heat pump, get behind dropping meat from your diet one day a week, be part of this transformation.” And for what? The same as now. Nothing changed about the status quo, the structures, the norms, what it’s possible to hope for and aspire to.

This creates a space for the fascists and the right to jump in and say, “the liberals have got nothing for you, and we have; they’ve ruined it for you.”

Ts: One big socio-economic trend of the last fifty years has been the divide between those with college degrees and those with a high school education. Thanks to various management techniques and algorithms, those in the latter group are seeing a massive decline in their control and autonomy at work. Think of the example of an Amazon delivery worker who, rather than being given the freedom to deliver their packages according to their own know-how, is controlled by an algorithm that demands that these packages are delivered in the most efficient way possible. How does this question of working-class control and autonomy relate to climate and the broader threat of disempowering and deskilling people?

CS: Absolutely correct. Surveys we’ve done have asked, what is an attractive benefit of green jobs? Working-class respondents don’t rate “green jobs” as such very highly. If a green job is the same Amazon gig but with more electric vehicles, that’s of limited appeal. Nothing of any real import is changed. The deskilling, the decreasing control over one’s work—that sense of a lack of freedom provides leverage for the right to attack net-zero policies.

The left and center left have very little to say about freedom, which is a big problem. If acting on climate change means sacrificing what little freedom I have left, then what value is that to me? I hear this a lot among the working class; this idea that the few remaining freedoms are going to be taken away from them by the same credentialled class.

This is connected to the question of place. About half the American adult population still lives within fifteen miles of their parents. I know plenty of people here in the UK for whom that’s the norm. For the middle class, in contrast, it’s normal to uproot oneself and go where the work is; place doesn’t matter. But it does matter to the working class. They understand climate change very much in terms of what’s happening to the trees in my street, what’s happening to the river down the road. This doesn’t help progress on climate change, but it reveals that it’s those immediate experiences of the environment rather than global atmospheric concentrations of CO2 that affect people’s ideas about climate. There’s a big divide between this strong, long standing connection with place and those working at the UN, IPCC, World Bank, concerned with the global.

Ts: What kind of shift has taken place in climate politics over the last three or four years? Lately, every election seems to be a climate election, with governments throwing enormous amounts of money and even coercive tools of economic statecraft at the problem. How should we make sense of these developments?

CS: States have taken, in relative terms, dramatic action in the name of climate (and competition). But the politics are still fragile. I think a big part of this is that the language of climate change remains an elite, technical language. It is opaque and impenetrable to most people, and it excludes the working class. The imperative political question is: how do we make that discussion about our future accessible to, and inclusive of, a broader range of voices?

My belief is that societies cannot organize effectively to cope with the impacts of climate change without a shared understanding of the future that awaits. Currently, representations of the net-zero future don’t do that. They are a denial of the best of human nature. They shut down the possibility of imagining something different in favor of a fantasy of more of the same, minus catastrophic climate change. With a better, shared understanding of the world we’re moving toward, we can better organize ourselves to live in that world, whatever that might mean, whatever that might look like.

Ts: Your book, Liberalism and the Challenge of Climate Change, came out last year. Could you tell us how you came to write this book?

CS: People with my background don’t really belong in the world that I find myself in—a middle class, privileged world of climate campaigning. My working-class background—broken family, no history of university education, lots of manual labor jobs—has given me an outsider’s perspective. I wasn’t brought up to expect that the world would respond to my desires. I wasn’t brought up to have much sense of agency; the world does stuff to me, I don’t do stuff to the world.

My book argues that the language and ideas used to address climate change are shaped by power relations—and that this language inadvertently accelerates the problem.

I must also own up to the anger that motivated my book. I believe Cormac McCarthy said that people write instead of blowing up the world. The anger is in part a product of working-class resentment against the middle class who is complacent about the status quo, and vicious when its privilege is threatened. The anger is also about being lied to. The lie being that the liberal middle classes of the global North are the carriers of the light, the masters of our future, the saviors of humanity. But liberalism is now destroying the foundations of life.

Filed Under