With India headed to elections this April, the ruling BJP is rolling out enormous publicity campaigns to promote its record on economic growth and Hindu nationalism. Central to Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s third bid for reelection is the narrative that the Indian economy continues to grow and remains open for business. Amid the ample flows of international finance, and support from Western capitals, Modi’s India is an increasingly ethno-nationalist state. This week, tens of millions of Hindus mobilized across the country as Modi inaugurated a Ram temple in Ayodhya, in the state of Uttar Pradesh. Built at the site of a Muslim mosque destroyed by Hindu extremists in 1992, the temple’s unveiling represents a major step in Hindu nationalism—and the symbolic end of India’s secular republic. The question as to whether Modi’s Hindutva agenda lies in contradiction with the economic liberalism that has defined much of BJP’s policy is on many commentators’ lips.

The BJP has long relied on a well-oiled marketing machine to win votes. The advertising blitz now underway recalls the party’s “India Shining” campaign of 2004, launched by the Ministry of Finance. Then, as now, images were plastered across the country, expressing optimism about the country’s economic performance and promoting liberal reforms. At the 2014 elections, Modi ran with the slogan of “good times,” promising development, a “muscular Hindu nation,” and a bright and glorious future.

To discuss these ad campaigns and the connections between the seemingly separate spheres of economic growth, national identity, and international politics, we talked to the Indian historian of nationalism, Ravinder Kaur. She is the associate professor of Modern South Asian studies at the University of Copenhagen, and the author of 4 books, including Brand New Nation: Capitalist Dreams and Nationalist Designs in 21st Century India, The People of India, Identity, Inequity and Inequality in India and China, and Since 1947: Partition Narratives among Punjabi Migrants of Delhi.

An interview with Ravinder Kaur

TIM SAHAY: Your book, Brand New Nation, looks at how countries were plugging into the liberal global economy of the 1990s to attract investment capital, and far from diminishing the importance of nation-states, rejuvenated ethno-nationalism. You’ve argued that in the Indian case, the “liberal” economy and “illiberal” hypernationalism of Modi’s BJP are not separate phenomena, but two strands of Hindutva’s vision. How would you characterize these connections?

Ravinder kaur: I begin my book in the 1990s, arguing that the last three decades of economic reforms basically transformed the nation into a commodity. I traced the ways in which India, the post colony, turned itself into an “emerging market.” Contrary to the understanding of globalization as a process imposed from the outside and resisted by local groups, I argue that economic “LPG” reforms—liberalization, privatization, globalization—were embraced by the policy elite in India. Initially, there was some political pushback against it, both within the BJP and Congress, but by the turn of the century, any resistance to them had disappeared.

This great transformation activated a seemingly unlikely alliance between global capitalism and hypernationalism, a foundation on which twenty-first century Hindu nationalism would begin taking shape.

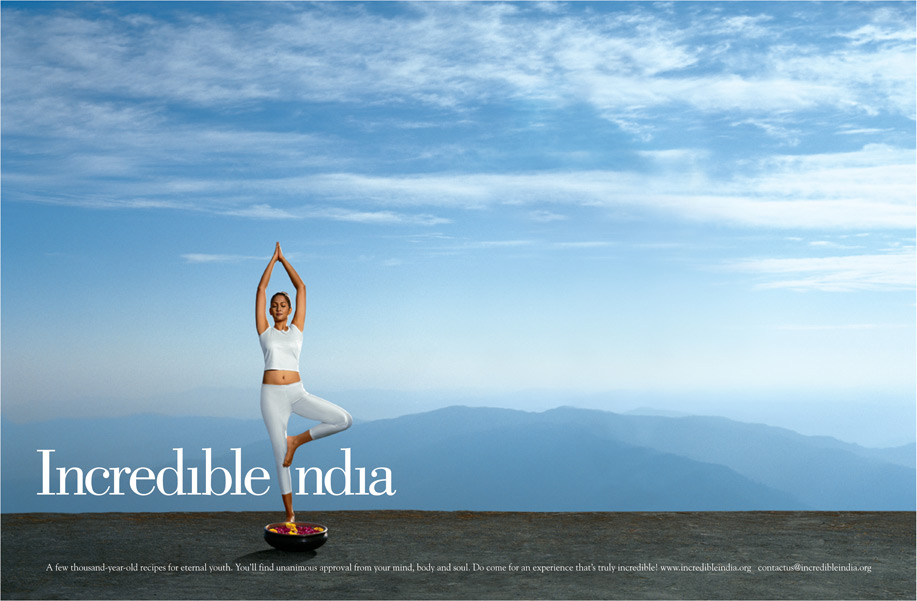

In the early 2000s, the government organized and funded mass publicity campaigns, such as “Incredible India” and “India Shining.” These were used to try to brand postcolonial India as a lucrative investment destination for global capital. These campaign ads showcased India as Hindu, rather than the multiethnic society that it is. The Brand India publicity material mostly appeared as a repackaging of cultural symbols—from yoga to Ayurveda, colorful festivals to nature, and a virtual absence of Muslims. These campaigns dovetailed with a broader cultural politics that sought to define who was included and who was excluded in India.

The question I took up in the book was: “What is a nation in the twenty-first century?” It leads us to a different set of answers. I elaborate on the idea of an “identity economy,” in which a national identity is put to work in the domain of the economy, and harnessed to boost the self-image, self-identity, and prestige of the nation. I look at ways the economic and the non-economic work together to produce a particular kind of nation form.

TS: What is unique about this project of national rejuvenation? China’s CCP has the story of a century of humiliation at the hands of Western powers, while the Indian BJP narrative has been a millennia of humiliation, of being conquered by foreigners, whether Muslim kings or British colonialists. These civilizationist-nationalist narratives violently flatten their history.

RK: The infusion of capital promises progress and prosperity, and is a sign of the nation’s arrival on the world stage. Capital appears as a curative force that can efface the shame of colonial subjugation and violence, and redeem the nation’s lost glory via economic growth.

Identity economy entails reimagining the nation as a commercial enclosure that can be put at the disposal of investors—its territory as a vast reservoir of untapped natural resources, its population as a “demographic dividend” that provides both labor and consumer markets to sustain growth, and its cultural essence to be turned into a corporate brand identity. Thus, the emergent nation form—the brand new nation—is erected not just upon the scaffolding of economic growth, but also the promise of civilizational glory and rejuvenation.

Stalled liberalization

TS: Could you specify the link between liberalizing policy changes to attract foreign capital and India’s domestic politics?

RK: One goal of these ad campaigns is to signal to the world that we are open for business. They seek to invite investment, both domestic and foreign. In India, much of the liberalization of the economy has taken place in the service sector, and the country’s service exports have boomed. There has also been an attempt to boost and open the manufacturing sector—as with the flagship program called “Make In India”—and turn the entire territory into a zone of production, with mixed results. Meanwhile, the vast agricultural sector—India remains a country where 46 percent of working age adults are engaged in farming—has been the last area to remain protected. When in 2020 the BJP made attempts to liberalize and deregulate farming, large-scale farmers’ protests broke out and forced the government to shelve its reforms.

Liberalization has not happened suddenly, as shock therapy, but gradually. There are regulatory requirements for Indian partnerships or joint ventures, rather than 100 percent foreign ownership. These projects lead to a lot of conflicts, as making land—especially farmland—available to investors is often fraught, and Modi’s land liberalization agenda too has stalled.

Likewise, modes of federal governance have changed a lot. India competes for foreign investments but, within India, different regions also compete with each other to lay claim to those investments. The current government has sought to create what’s known as the “one nation” model—one nation, one tax, one market. This entails greater centralization of economic and political power in Delhi and the weakening of the regional power structures. This has been attempted, for example, through a common Goods and Services tax system that centralizes revenue collection, thus giving greater power to the central government. That too is a project to unify the entire territory, both in an economic and cultural sense.

TS: The BJP’s major support has come from the rising Hindu middle classes of North India. Is the success of Modi and the BJP a bottom-up expression of a newly prosperous Indian middle class?

RK: These policy initiatives have always been led by the elite; to think that they have ever had a grassroots constituency is a mistake. Only after the policies are made by the elite does the question of selling it to the population come up. This is where mass campaigns or political spectacle have become a central component of Indian politics.

What I analyze in the book is how these mass publicity campaigns emerged as a form of governance. In the run up to the 2004 election, BJP prime minister Atal Bihari Vajpeyi launched the “India Shining” campaign, which celebrated the high growth rates the country was reaping while encouraging higher consumption among newly affluent Indians. When the BJP then lost the 2004 election, many blamed the “India Shining” campaign. What people forget is that though the government lost the election, its liberal economic reform program had already become hegemonic. The Congress Party’s counter slogan to the BJP’s “India Shining” was “Aam Aadmi ko kya mila” (“What did the common person gain out of it?”). The Congress-led United Progressive Alliance government (2004–2014) also wanted to deliver “reforms with a human face.”

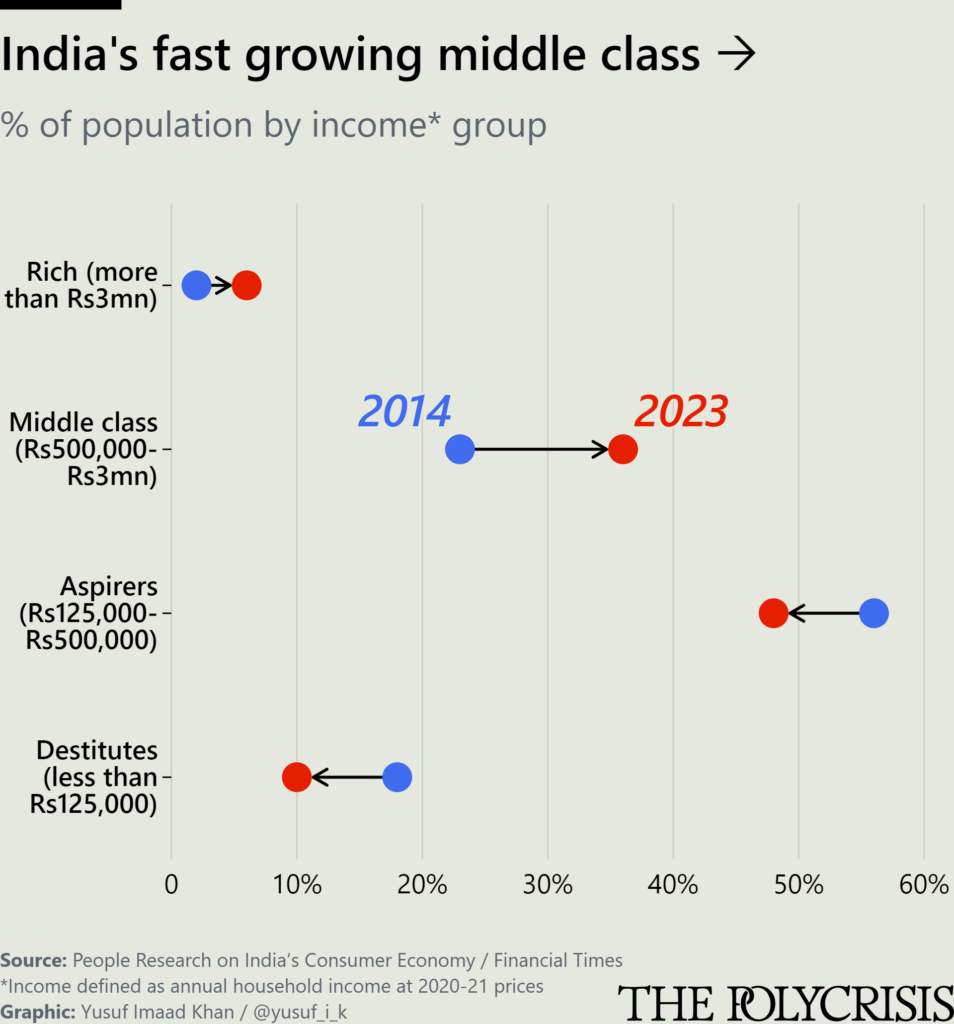

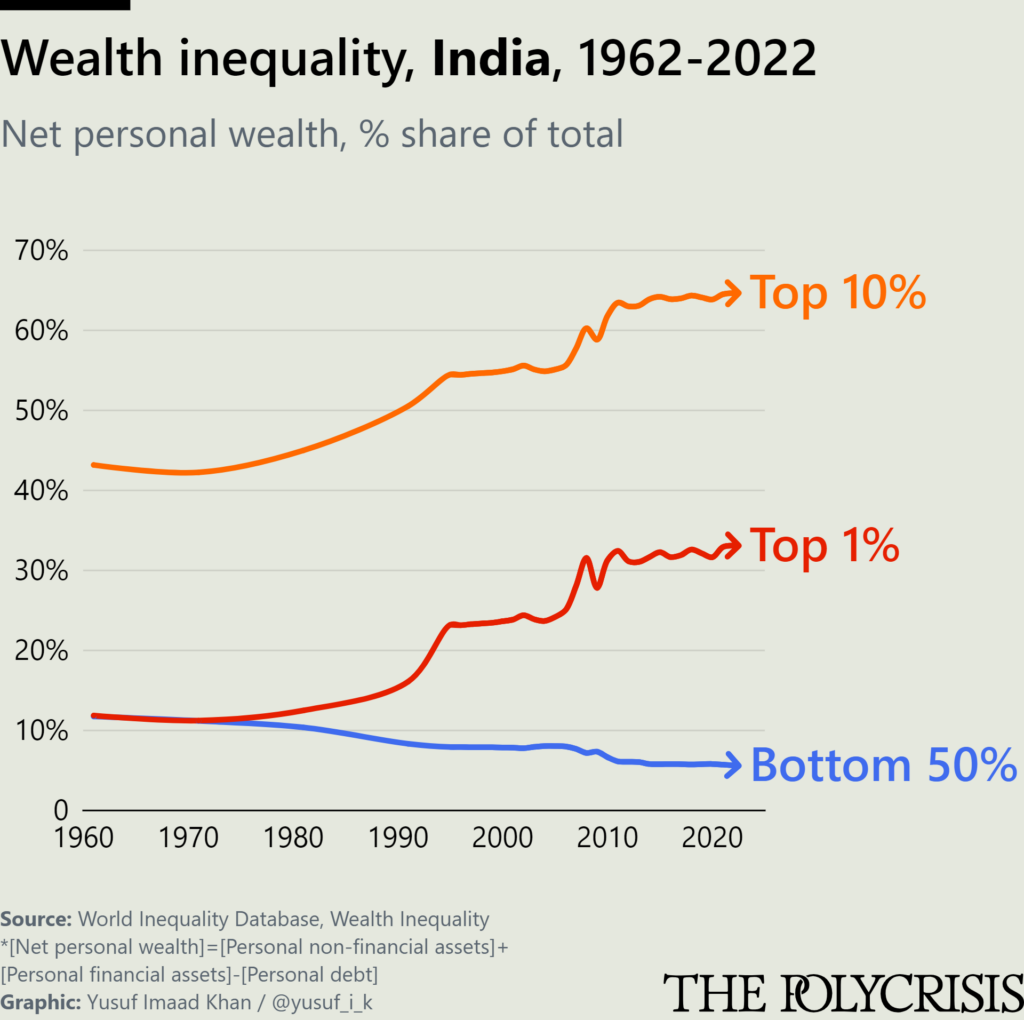

TS: When Modi came to power in 2014 his election campaign promised acche din: India Shining 2.0. Despite the optimism from many corners, India’s economy has underperformed since then. Growth rates have fallen, underemployment remains high, investors have been burnt, and inequality is skyrocketing. How has Modi’s government responded to all this? Is it concerned about inequality or is it totally committed to an oligarchic project with the Adani and Ambani families at the core?

Ravinder kaur: I think it’s a balancing act here. Firstly, inequality has certainly widened in India since Modi came to power, and Adani and Ambani’s wealth have skyrocketed.

At the same time, the Modi government has kept in place many of the welfarist policies established by the UPA. For example, it maintained the Right to Work (National Rural Employment Guarantee) schemes, which guaranteed 100 days of work to 64 million rural workers, especially women. It also preserved the Right to Food program. Likewise, the BJP increased social welfare goods. The most prominent successes have been targeted poverty alleviation programs: the distribution of cooking gas cylinders, widening access to bank accounts, and direct cash transfers. So it’s not the case that Modi simply embraced a free-market model, which would have had its own major obstacles in a country the size of India.

A key difference between the UPA and the current government is how welfare is administered. Rather than a basic provision from the state, welfare provisions are marketed and advertised as a benevolent gift from the BJP government, indeed as the beneficence of Modi himself. This is not welfare as a citizen’s right but as a gift one should be grateful for. These branding exercises have reaped electoral benefits for the BJP, especially among rural women in Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh.

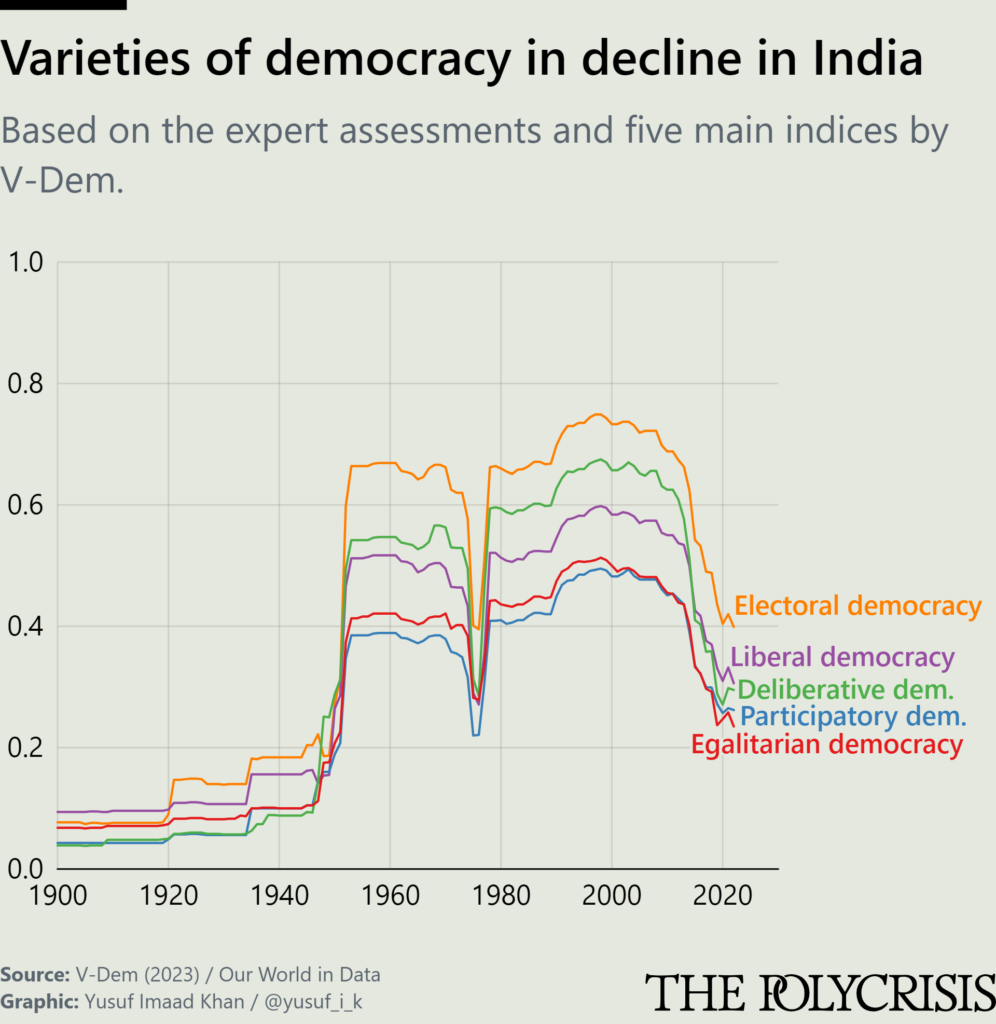

TS: Why has the rise of Brand India gone hand in hand with the decline in liberal democracy?

RK: India’s efforts to brand itself as the “world’s largest democracy” helped project it as an alternative to an authoritarian China—whence the paradox: under Modi, the very democratic advantage that shaped Brand India’s image on the world stage entailed its steady erosion at home. Hindutva politics recognises this contradiction: it cashes in on India’s democratic credentials to gain external recognition even as it weakens democratic institutions at home. Consider the unabashed implementation of the hardline Hindutva agenda in Modi’s second term—from the revocation of the special status of Kashmir in August 2019, the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) that excluded Muslims, to the inauguration of the Ram temple in Ayodhya this week. What characterizes this moment of majoritarian muscle flexing is the heavy-handed suppression of dissent (the crux of democracy), especially in university spaces, and how the act of protest itself has been criminalized by the State.

Alignments

TS: What do you make of Modi’s India positioning the country as a pro-West bulwark against China? This project seems like it would be a momentous shift away from India’s long-held foreign policy of nonalignment.

RK: If India is positioned as a bulwark against China, this is largely thanks to efforts by foreign powers rather than Modi. With much of the world “derisking” its economies from China, India now finds itself in a happy position. It is the only country which rivals China in terms of scale of population.

The old Indian project of pan-Asian unity is long gone. Nehru was very much invested in that, but it came undone thanks to the Indo-China War in 1962. The ongoing border conflict between India and China has caused immense nationalist mobilization on both sides. So regardless of which party is in power, given the security threat China poses to India, any government would be pro-Western.

TS: India today relies upon extremely anti-Muslim, majoritarian, identity-based politics, but it’s not clear to me that the Hindu extremists in Modi’s party are entirely under his control. How unstable is this as a basis for rule in a country with over 200 million Muslims and other minorities?

RK: Whether the growing strength of Hindutva will lead to some social breakdown that causes investment capital to flee, we don’t know. For now, India remains profitable to many, such that the world more or less wishes India well. The United States grants Modi’s violent project a carte blanche. This provides a high degree of security. But the impacts of a further deteriorating social fabric remain to be seen. Such projects can never truly be contained.

TS: Modi has also positioned India as a champion of the Global South. He has argued that India faces massive challenges and wants reform of the unequal Westen-led international order—just like developing countries in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. At last year’s G20, India championed the goals of debt relief, poverty reduction, and sustainable development. What makes this project different from the non-aligned movement of the 1950s–60s?

RK: On the face of it, it looks as if the 1950s have returned. But much is different this time. Countries across Asia, Africa, and Latin America are no longer impoverished in the way they were at the time of decolonization in the mid-twentieth century, and there is tremendous inequality within the global South. Meanwhile, in terms of foreign-policy influence, larger and more prosperous countries, like those in BRICS, now have substantial clout in the world, and are seeking to come together.

So this is very different from the Non-Aligned Movement, which many people did not take seriously, because it lacked economic or military power. But nevertheless, the old Non-Aligned Movement always had very strong currency, primarily because it came with very strong moral arguments about anti-racism, decolonization, and nuclear disarmament. The current mobilizations have nothing like that. There is no alternative vision of the world that they are trying to put forward, but instead new ways to plug into the capitalist world-system for their own advantage.

Filed Under