It is now over a month since Hamas launched its attack on Israel, killing an estimated 1,400 Israelis and taking more than 200 people hostage. Israel’s response has, in Netanyahu’s words, sought to “crush and destroy” Hamas, but the main victims of his campaign are Gazan civilians. Daily air and artillery pounding has so far killed more than 10,000 Palestinians—including four thousand children—and destroyed large tracts of public infrastructure: schools, hospitals, universities. Food, electricity, and water have all been cut off by Israel’s siege, contributing to a gathering humanitarian crisis. Malnutrition, overcrowding and disease often take more lives than bombs.

To shed light on some on the cleavages in Israeli society that surround Netanyahu’s leadership, and the wider regional context of Israel’s assault on Gaza, we interviewed the Israeli historian Guy Laron in late October. Guy Laron is a senior lecturer of international relations at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and the author of two books: Origins of the Suez Crisis and The Six-Day War.

An interview with Guy Laron

Tim Sahay: Bibi Netanyahu is Israel’s longest serving prime minister, surviving many corruption scandals and public protests. In a tweet you said: “the Bibi doctrine has collapsed: it created a Hamas monster, Apartheid in the West Bank, and a hollow state. But he’s not letting go of his efforts to create a personalist dictatorship.” What is the Netanyahu doctrine? What are its bases of domestic support?

Guy Laron: It started in 2009, when Netanyahu came back to power. Nobody then thought that he would be in power this long. The starting point of the Bibi doctrine is neoliberalism. From that you can derive all other aspects of his policy. The doctrine is upheld by his domestic coalition. That is where his foreign policy begins. What he cares about is getting the support of two demographically ascending sectors of Israel’s society: the ultra-Orthodox and the settlers in the West Bank.

The ultra-Orthodox are not that important for his foreign policy, but they are important for his domestic policy. While the rest of society suffers cuts in spending for public health, public education, and public transport, the ultra-Orthodox are exempt from cuts.

Next is support for settlers in the West Bank. It’s an open secret that there is a welfare state in Israel, which exists only in the West Bank, and only for Jews. Each time Netanyahu wrote new legislation—to make the state smaller, the budget smaller, the taxes lighter—parties representing the ultra-Orthodox and the settlers supported him. In everything he does, then, Netanyahu needs to show settlers in the West Bank that he is meeting their needs.

This is where Hamas comes in. What is the greatest threat for the settlers in the West Bank? It is a scenario of a Palestinian unity government between Fatah (the faction which governs the West Bank) and Hamas in the Gaza strip. It hasn’t been the case for the last five years, but previously there have been opportunities for a Palestinian unity government to emerge across Gaza and the West Bank. In that scenario, with a unified political leadership for the Palestinians, Netanyahu could not postpone negotiations over a Palestinian state.

Each time such unity was possible, Netanyahu derailed it. His overall strategy has been to ensure that Hamas would remain strong in the Gaza Strip, and maintain a split in the Palestinian elite. One example of this strategy was his approval of an arrangement by which Qatar sent funds into Gaza, to Hamas. The resulting status quo was Netanyahu maintaining the division of parts of the Palestinian state, while costing Israel nothing.

“Anyone who wants to foil the establishment of a Palestinian state needs to support the strengthening of Hamas and the transfer of funds to Hamas.”— Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu at a Likud faction meeting in March 2019, as quoted in Haaretz

Until October 7, even his critics understood his divide-and-conquer strategy as a stroke of genius. Hamas’s attack changed that. This is why, for example, the Haaretz Editorial Board was quick to lay all the blame for Israeli deaths on that day at Netanyahu’s feet.

Israel as “energy hub” turning into personalist autocracy

TS: You have researched Netanyahu’s ambition to remake Israel’s economy into an “energy hub” and a “transit state” for oil and gas from the Eastern Mediterranean to Europe. What have you found?

GL: Although Netanyahu is identified with the idea of “startup nation”—Israeli high tech—that’s not really his doing. He reaps rewards of policies of predecessor governments.

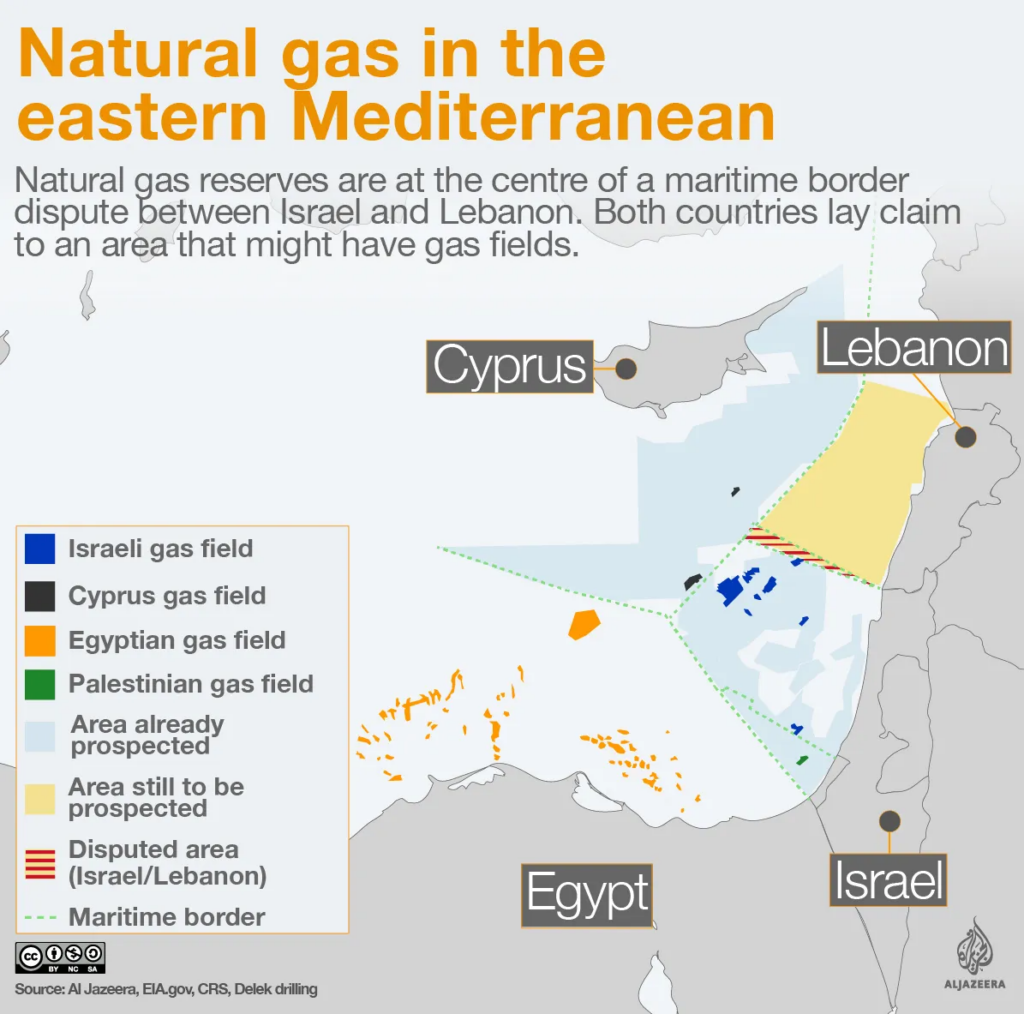

Netanyahu has long wanted to turn Israel into a resource economy and an energy hub. Ever since the 2010 discovery of enormous gas fields in the territorial waters of Israel—the Tamar gas field (200 billion cubic meters of reserves) and more famously the Leviathan gas field (600 billion cubic meters of reserves). The aim is to supply Europe from these two offshore fields.

There was some existing infrastructure he could work with. For example, the secret Eilat-Ashkelon pipeline, that Israel has been working on since 1957, which connects the Red Sea to the Mediterranean. From 1957, Israel doubled the capacity of that pipeline. Recently—exactly when is classified—Israel made the pipeline bidirectional. Previously one could only stream liquid oil in one direction from the Red Sea to the Mediterranean. After he became PM in 2021, Netanyahu approved the much delayed development of the far smaller gas field in the territorial waters of Gaza, which has reserves of 30 billion cubic meters.

Becoming a player in the energy market and establishing itself as a transit state is useful for national security as well. That way, Israel could pitch itself to the West as a safety valve: “If something happens to the Suez Canal, we are here.”

TS: The Gaza Marine gas field is within Gaza’s territorial waters, but the Israeli government has barred Gaza from developing it.

GL: Yes. Until recently, Israel did not allow British Petroleum to develop the Gaza marine gas field. But the pressure to develop the Leviathan and Tamar has increased given European energy needs since the war in Ukraine, when the EU voluntarily cut off Russian oil and gas. In March, Netanyahu gave the final green light after meeting with Italian prime minister Georgia Meloni in Italy to discuss common interests. Italy wants to become the energy junction of Europe, the meeting point of various gas fields from Algeria up to Cyprus, Israel, and Egypt. Netanyahu discussed with Meloni how to connect the Leviathan gas field to Italy via Cyprus partnering with Eni, Italy’s national champion oil & gas firm.

TS: What is the relationship between this energy development agenda and the Bibi doctrine?

GL: More and more, much like Putin, Netanyahu feels that the educated middle class that made Israel a powerhouse in high tech and arts is a burden. They were interfering with his quest to create a personalist dictatorship. These are the people he has been trying to drive off with his judicial coup in the last year—he no longer needs them. He’ll have revenue from transit fees, gas exports, and Israel’s military industrial complex. These are the only sectors of the economy he’s focused on.

ts: One viewpoint is that Netanyahu is trying to imitate an Arab oil Kingdom, where the ruler is relatively insulated from democracy, in that the fiscal revenues of the state are not dependent upon taxing people or firms, but on extraction, royalties and oil revenues. That gives the leader a lot of freedom with few checks and balances, and pushes the country in the direction of a personalist autocracy. Is Netanyahu consciously pursuing that goal, or is everything with Netanyahu just improvisation?

GL: The educated middle class in Israel is important not just economically but for the functioning of the army. Netanyahu had this idea of investing in a “smart, agile, small” army. And while this too is a state secret, my educated guess is that he put a lot of money into Israel’s nuclear capabilities.

What is better known is investment in the three technologically advanced arms of the military: the Navy, the Air Force, and the Intelligence Corps. But that investment gives the educated middle classes a veto position in Israel: once Netanyahu began his judicial coup, pilots in the Air Force said “we won’t volunteer for active service.” Those reservists are considered the most important for the functioning of Israel’s military because they have a lot of experience. Netanyahu refused to relent with his judicial coup saying, “Israel can live without one or two squadrons. But it can’t live without a functioning government.” That’s from a leader who has been beating the drum for war with Iran. Now, suddenly, he says Israel doesn’t need the air force that much!

The Abraham Accords and the “axis of resistance”

ts: For more than a decade, the foreign policy of the Netanyahu doctrine characterized Iran as the “axis of evil” and created a coalition with Arab autocrats—the Abraham accords—to contain it. How does Iran look upon Israel?

GL: Netanyahu has long been Iran’s worst enemy in the region. Over the last decade, Mossad got a lot of money to run a series of operations that humiliated Iran by assassinating leading Iranian nuclear scientists and high officials in the Iranian Revolutionary Guards. There were also several cyber warfare operations. The Stuxnet virus that disabled Iranian uranium centrifuges is the most well known. But other incidents include jamming traffic lights in Tehran, or displaying anti-regime slogans on electronic billboards.

Until the October 7 Hamas attack, which I don’t believe was authorized by Tehran, the Iranians thought their best option was to sit this one out, to let Israel’s internal political strife play out, and hope that the opposition would succeed in toppling Netanyahu. In interviews over the past months, Hezbollah’s leader Nasarallah talked like an analyst working for the Israeli opposition, shrewdly describing how Netanyahu is trying to create a one man rule that was destroying Israel from the inside.

Iran wants to see Netanyahu gone. The question is the method. Obviously, Iran is upset about the Abraham Accords between Israel and the Gulf kingdoms, which they view as an anti-Iran alliance. The Accords also had a military component with summits between Israeli and Gulf generals. The idea was to turn airfields in the UAE, Bahrain, and Saudi Arabia into further outposts of the Israeli Air Force.

ts: What has been the longer-term backdrop of changes within the Arab world that led them towards the Abraham Accords? Your books on the Six Day War in 1967 and the Suez crisis in 1956 pay enormous attention to the traditional powers of the Arab world: Egypt and Syria, which have since declined. How is it that the UAE and Saudi Arabia are now more powerful and leading the detente with Israel?

GL: Most simply, the Gulf Kingdoms have a rivalry with Iran over hegemony in the Gulf. Even Iran under the Shah was always a strong player in the Gulf. The monarchist regimes fought but they didn’t have irreconcilable differences. Iran after 1979 is a different story. Iran that is using Shiite minorities throughout the region—and particularly around the oil fields in eastern Saudi Arabia—is a problem for the Kingdoms. There is a big Shiite population around the oil fields in eastern Saudi Arabia. Within that framework, for the Gulf Kingdoms to be allied with Israel against Iran seemed like a good idea.

It’s been a long time since Egypt and Syria have called the shots in the Arab world. After the oil shock of the 1970s, the center of power moved to the Persian Gulf. Egypt did have a leading position in the Arab world for many years, but ever since the Arab spring in 2011, the internal crisis within Egypt has precluded it from playing a regional role. The biggest issue for Egypt today is its external debt and the growing crisis for the Sisi regime around soaring energy, food, and debt servicing costs after the Ukraine war.

When Egypt was ruled by Nasser, it was a transit state and so earned high transit fees. Almost all the wars that Nasser got into were about controlling the Suez Canal. When King Faisal or the Shah looked at Nasser, they thought “he was out to extort us.” I think they were basically right. There was a deep rivalry between Nasser”s Egypt and the conservative Gulf Kingdoms. Sadat changed the rules of the game when he approached both King Faisal and the Shah, saying “why not work together?” That was the organizing idea behind the October War in 1973. Namely, that Egypt would launch a military maneuver, and Saudi Arabia would begin using the economic weapon, the oil weapon.

It was from then that the center of power moved away from Egypt and toward Saudi Arabia. Egypt can serve as an intermediary between Hamas and Israel. But in terms of who decides the result of an Arab summit between Arab leaders, President’s Sisi’s Egypt would come as a beggar to the richer Gulf kingdoms.

US-Israel military and political engagement

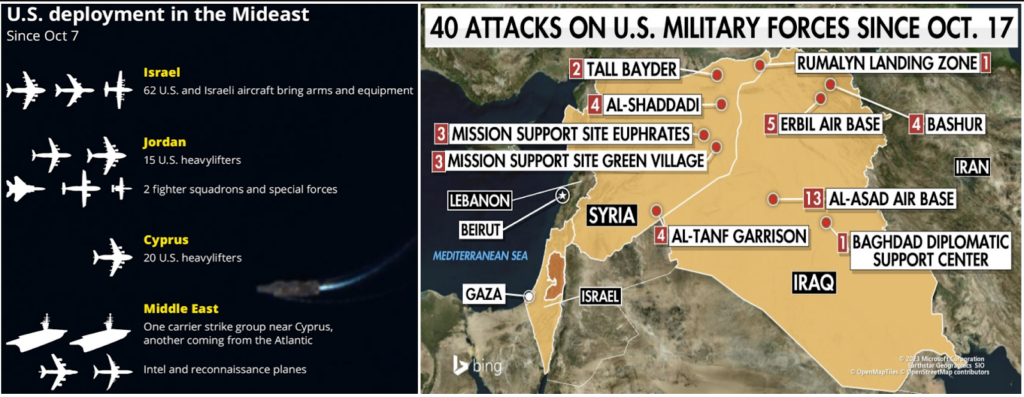

ts: US Secretary of State Blinken has made visits to every capital across the Middle East in the last month. He has gone to Egypt, Jordan, Israel, Bahrain, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Cyprus, Turkey, and Iraq. What is he trying to achieve? Secondly, Haaretz reported in October on a massive US-Israel air lift of arms and equipment that has been in continuous operation since October 7, which hasn’t received much attention in the US press. Does this airlift make it a joint US-Israel war?

GL: I’m speculating here, of course. Blinken’s visits played an important role in decision making in Washington. Their primary goal was to understand what capitals are thinking. In the lead up to Biden’s visit to Israel, Blinken underscored the understanding that an Israeli operation in Gaza would not be like any previous operation. That the rage in the Arab world is so intense among the public that governments like Jordan and Egypt feeling the political earthquake of October 7.

On October 16, Blinken participated in a seven hour long Israeli cabinet meeting. Pentagon chief Lloyd Austin, speaks daily with Yoav Gallant, the Minister of Defense. The general message Blinken conveyed to Israel’s cabinet was to refrain from a ground operation until the US figures out a “day after” plan and to contain any general escalation in the region.

Such deep American involvement also shows you how weak Israel is. The American understanding from Blinken’s visit to Israel and to leading Arab countries was that the government in Israel is crazy and unreliable, and that there was a high risk of a Middle east conflagration. Hence the Biden administration’s insistence to the Israeli war cabinet on planning. What will the political ends of an Israeli operation in Gaza be? The American plan is to get the Palestinian Authority to administer a post-Hamas Gaza with Saudi backing.

Other than that, we have two US aircraft carrier strike forces: the Gerald Ford, sitting next to Cyprus, and the Eisenhower stationed somewhere near the Persian Gulf. That creates an umbrella of anti-missile defense. My guess is that the Americans told the Israeli cabinet, “whether or not you invade Gaza or not, you need to give us the time to secure our assets in the Middle East.”

This unprecedented US naval maneuver is part of the effort to deter Iran, Hezbollah in Lebanon, Houthis in Yemen, and militias in Iraq and Syria. The reasoning seems to be to deter these players, in the most persuasive way possible, not to jump into the fray. Sending two aircraft carriers is the clearest signal to Iran: “this will be bad for us, the US, but it will be horrible for you.”

Going back to your question, I think the Blinken visit created a reassessment in Washington, and the most important conclusion was that the Americans need to be much more involved, both politically and militarily.

ts: We are in the midst of a much broader New Cold War—a Hot war with Russia, a Cold war with China. Your books were about how Cold War dynamics shaped the modern Middle East and the global South. What do Arab-Israel, and US-Israel, relations look like within the context of an emerging de facto alliance between Iran, Russia, and China, each of whom have found themselves being contained by the US?

GL: I think this broader Cold War won’t end, at least in the next few years. If it’s a new Cold War, then you would have look at the first Cold War solution to Europe’s energy problems. The first Cold War arrangement was to replace Polish coal, Romanian oil, and Soviet oil (that Europe was dependent on before 1947) with oil from the Persian Gulf.

You can see the same thing happening now. There are new centers of production, not just in the Persian Gulf, but also in North Africa. Algeria will be very important going forward, as will Libya. There are talks about connecting Nigeria with Algeria through a trans-Saharan pipeline. And in that jigsaw, Israel will be important as it was in the past as a transit area and an energy hub. Whether it can fulfill that role today is an open question. Israel is very much a divided society.

ts: Israel and America’s window of legitimacy appears to be shrinking each day. Everyone from the Pope to the Financial Times, UN agencies to 120 governments of all political stripes at the UN are calling for a ceasefire. Meanwhile, the US Congress and the President are staunchly opposed (despite decisive pro-ceasefire majorities in the polls) and Netanyahu is now talking of an “indefinite” re-occupation of Gaza. How does this end?

GL: This Israeli operation in Gaza could continue for a few more weeks, but not much longer than that. Public opinion in the world and the Middle East, the deteriorating Israeli economy, and the fact that Israel is awash with the tens of thousands of internal refugees (people who fled the border regions both in the south and the north of the country due to fighting with Hamas and Hezbollah) would not allow the IDF enough time to achieve their stated goal of defeating Hamas. At the end of the operation, with a soaring civilian death count, the IDF will point out some tactical achievements: some ruined tunnels, some dead Hamas officers—but little more than that.

Then a bitter and protracted struggle would begin inside Israel over the question of whether Netanyahu exits public life. As long as he is around, he will not allow the Gaza crisis to be solved and it would continue to simmer. Only after his resignation—if it ever happens—will a window of opportunity be opened up to create a more stable settlement between Israel and the Palestinains living in Gaza and the West Bank.

Filed Under