Leaders need followers. Last month, US National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan delivered a speech outlining the Biden administration’s international economic policy at the Brookings Institute in Washington. The “New Washington Consensus” was not directed at citizens but at capitals abroad. Sullivan’s speech took aim at the rise of global Trumpism. He addressed a question posed by social democrats the world over: Why can’t the center hold? An erosion of legitimacy, he argued, is at the core of the problem. In the face of compounding crises—economic stagnation, political polarization, and the climate emergency—a new reconstruction agenda is required.

Hegemony, however, is not the ability to prevail—that’s dominance—but the willingness of others to follow (under constraint), and the capacity to set agendas. Sullivan’s speech frames those common problems faced by countries and provides a menu of solutions: full employment, local content requirements, subsidies for manufacturers, loan guarantees, place-based incentives, pro-labor provisions, public R&D, tax the rich for others to creatively adapt to their domestic political economies.

Gone are the shibboleths of previous US administrations that extolled free trade, open capital flows and fiscal discipline. De-risking state interventionism is here. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen laid out the logic of “modern supply-side economics,” while Biden’s former chief economic advisor Brian Deese said the administration won’t accept “that the individualized decisions of those looking only at their private bottom lines will put us behind in key sectors.” Since neither climate, inequality, nor the rise of China could be tackled by the market, he added, “the state had to step in.”

On May 19, G7 leaders will meet in Hiroshima. A year since the Infrastructure Investment & Jobs Act, CHIPS & Science Act, and Inflation Reduction Act became law in the US, the rules about what qualifies for tax credits are being vigorously contested. But firms are gobbling up the carrots. The White House announced last month that vast investments had already been secured, including over $225 billion in clean energy and electric vehicles, $200 billion in chips, and about $15 billion in biomanufacturing. There are multiple reports of European and East Asian companies chasing those carrots and relocating planned facilities to the US. Having learned hard lessons about blowback and “leakage” with Russia sanctions, the US is coordinating with Japan and other allies to “derisk” its relationship with China by negotiating export controls on chips and diversifying sensitive supply chains, such as for transition minerals.

While the New Washington Consensus offers allies carte blanche on the interventionist economic tools they seek to apply domestically, it’s up to them to “crowd in” private investment and find fiscal space. Biden’s green industrial strategy prioritizes solving domestic inequalities rather than global ones. Its priority is using state power to actively steer markets that have proven incapable of providing public goods and broad-based growth.

Biden’s “foreign policy for the middle class” anchors the agenda. The basis of that framing originates in a 2020 report based on a two-year project by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace that surveyed Americans in Colorado, Nebraska and Ohio. By the time the report was published, Sullivan and several of his coauthors—including Jennifer Harris, Salman Ahmad, and William Burns—were senior officials in the Biden White House.

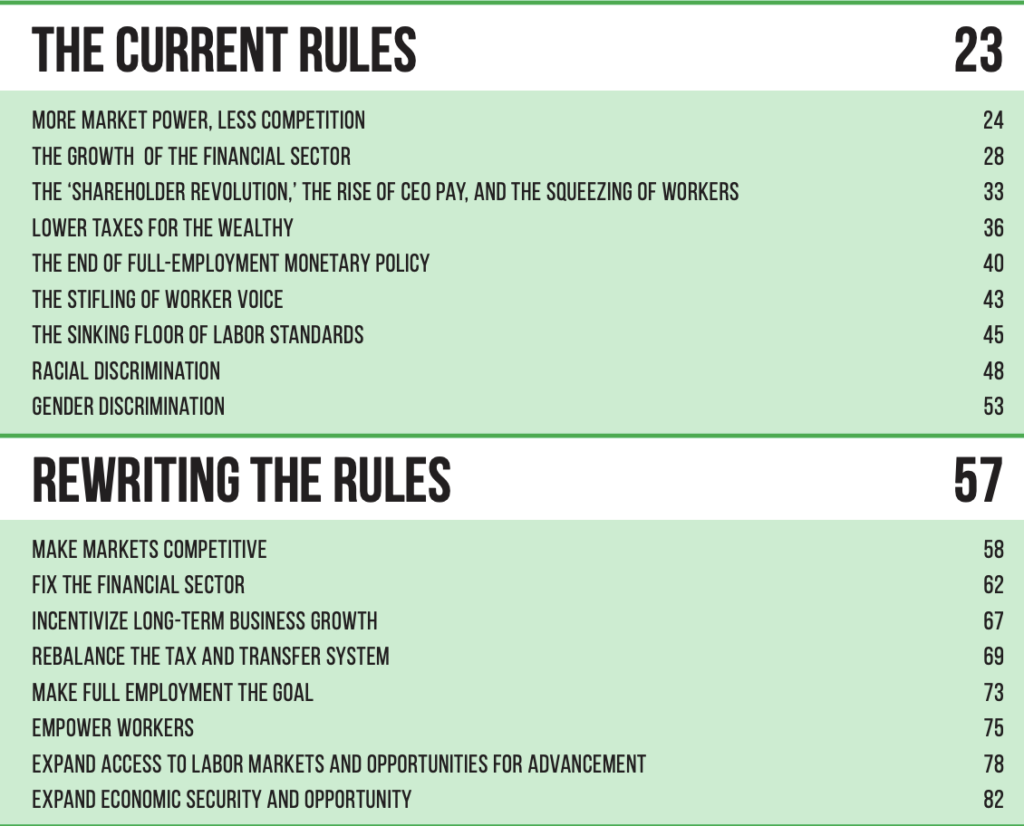

The Carnegie report called into question a longstanding presumption of Beltway politics: that foreign and domestic policy should be neatly siloed. It suggested that the two realms could be mutually reinforcing. To “credibly assert global leadership,” it asserted, the country must “get its own house in order.”

The report set out a shift away from laissez-faire trade, liberalization, and globalization, yet was at pains to insist it was not pursuing a Trump-style America First retreat. Trade itself was not the problem, it argued, so much as the breakdown in the social contract between business, government, and labor to mitigate the effect of a world shaped by global corporations and labor-saving technology. The country’s own middle classes would be likely unmoved by “restoring US primacy in a unipolar world,” it stated, but might be more supportive of strengthening foreign alliances that address a spectrum of issues “from pandemics to cyber attacks to unsecure weapons of mass destruction and climate change—that could imperil middle-class security and prosperity.”

Is it too costly?

Leaders on the continent responded to the IRA with outcry, suggesting it would prompt a subsidies race to the bottom. For its part, the EU’s main preoccupation is European stability, as well as EU-US competitiveness. The possibility of transatlantic fracture is real. Loosening fiscal and state-aid rules could mean more subsidies for French and German firms. Re-industrialization in the core and further de-industrialization in southern EU countries would risk fragmenting the single market.

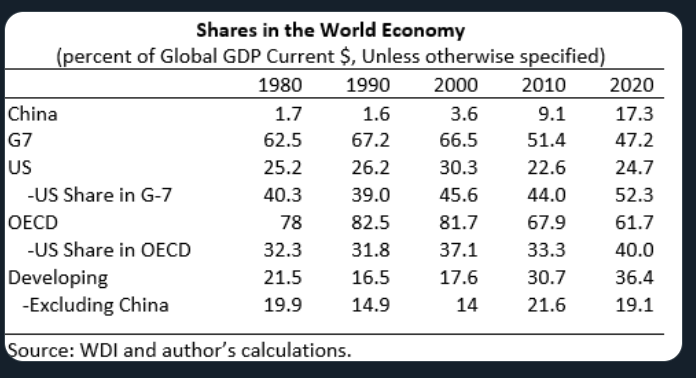

The US is in a unique position. As the main reserve currency issuer it, unlike many countries, runs an external deficit. As such—and notwithstanding GOP debt brinkmanship—it can afford to subsidize heavily. It also has a huge internal consumer market and is less intertwined with Chinese supply chains than some Asian countries. It has fared relatively well among G7 countries in the recent decades of globalization:

US policies are not radically out of step with those of other wealthy countries in recent years. Traces of Bidenomics can be seen in the “Leveling-Up” agenda of the Conservative government in the UK, albeit on a far smaller scale. Today, the Labour Party is proposing 280 billion pounds for a “green prosperity plan” over a decade, including publicly owned renewable Great British Energy utility, and a National Investment bank—coordinated with the Bank of England and Treasury.

Europe meanwhile was developing its own “green deal” agenda even before Covid. Over the past three years, exemptions have been made to allow common debt issuance and state support of national companies. These marked a shift in the bloc’s fundamental rules that ensure member states are on an “even playing field.” Emmanuel Macron last week announced a French green industrial strategy, declaring his government will seize the same tools used by both “partners and rivals”: tax credits to subsidize clean tech investment, local content rules for electric vehicles (EVs) and batteries (plus a EV consumer subsidy of €7000).

No Washington Consensus for developing economies

India and other big middle-income countries are in a very different position. Having declined to support western sanctions on Russia, many are wary of aligning with the US in ways that would threaten their economic relationship with China. Lula’s election in Brazil has sparked the re-emergence of South-South solidarity networks. The EV boom has spurred talk of a “lithium OPEC,” and Chile is now proposing nationalization of its lithium industry. Indonesia has been for years requiring foreign companies to refine its nickel domestically for EV batteries.

As to the question of what carrots the G7 might offer to countries in the global South, the details remain hazy. Last September, in our inaugural essay for The Polycrisis, we laid out what the countries flirting with a new non-alignment wanted:

1. Core technologies to power future growth;

2. Advanced military hardware for enhanced security;

3. The upper hand in trade negotiations with Europe, the US, and the new Russia-China bloc;

4. The ability to buy essential commodities like food, energy, metals and fertilizers from the new Russian-Chinese bloc;

5. Better terms to restructure their debt to Western and Chinese creditors during a punishing global dollar debt crisis that threatens their sovereignty.

Japan has made “global South outreach” a focus of its G7 presidency for 2023, and some potential, albeit patchy, efforts can be seen. The finance ministers’ meeting last week in Niigata produced a 26-point communique that included several references to emerging market and developing economies. It highlighted the importance of debt restructuring, of MDB reforms, and of better quality FDI.

That said, despite vaccine apartheid, the question of technology transfer has not been addressed, nor has the issue of securing essential supplies like food and energy amid geopolitical shocks to commodity markets.

The G7 finance ministers did, however, reference a new collaboration with the World Bank, to “help developing countries move up the supply chain” for EVs, solar panels, and storage. Timelines are vague, but policy guidance promotes joint R&D, and commits to unspecified support for low- and middle-income countries. It mentions using tools like “tax incentives, subsidies, guarantees and public loan and investment”—exactly the tools now being embraced at home by wealthy countries.

Without wide-ranging reforms to Bretton Woods institutions and other parts of the international monetary system, most developing countries remain reliant on costly and fickle sources of foreign investment capital, while remaining exposed to an IMF that imposes austerity measures and punitive surcharges whenever they stumble.

Sullivan’s speech assured its unambiguous commitment “to not leaving our friends behind.” While the US will “unapologetically pursue our industrial strategy at home,” he said, “we want them to join us.” But there is little sign of how deindustrializing developing countries might join the US or its G7 peers, whose leaders will be concerned with tightening Russian sanctions when they meet in Hiroshima. EU diplomat Josep Borrell told the Financial Times that Europe can’t take for granted that [developing countries] are on our side,” and must demonstrate support for their development needs, rather than forcing them to choose sides.

But there is no equivalent to the 2020 Carnegie report suggesting a path to reconcile tensions between security and domestic political economy in the global South, and paving the way for substantive change. The G7 has done nothing to address painful debt burdens in Africa. Its infrastructure initiative, PGII—viewed as an attempt to counter China’s BRI—is under-resourced. Bretton Woods quota reforms are idling, and SDRs are under-channeled.

After the G7, the next time the global South will be on the agenda will be the June Summit for a New Global Finance, to be hosted in Paris. The summit is inspired by the Bridgetown initiative, which was developed by Barbados and proposed concrete measures to improve developing countries’ access to finance for development and climate. After some confusion on the agenda, the Elysee promises the summit will “build a new contract with the North and the South.” It is also, notably, explicitly pledge-free.

Filed Under