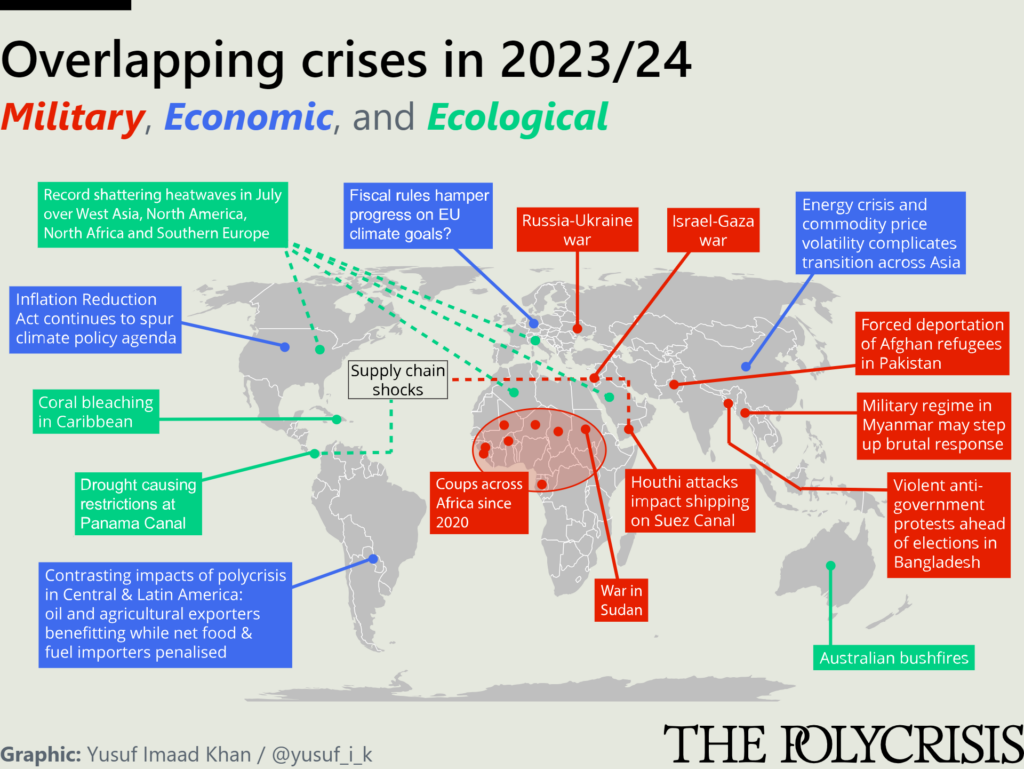

When we launched The Polycrisis a year ago, we set out to examine the intersecting crises in the economy, energy system, commodities markets, geopolitics, and climate. Our aim was to break intellectual and political silos to give a fuller picture of what’s going on: security and climate, political economy and commodities, domestic and foreign politics, macroeconomics and populism. In the meantime, our world crisis of ecology, economics, and empire, has continued to metastasize. It is, as Nancy Fraser put it, shaking confidence in established worldviews and ruling elites everywhere.

In twenty-eight newsletters, ten articles by contributors, and four panels with experts so far, we have mapped four main shifts:

Global South left high and dry

A new Washington Consensus has arrived. Following the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), Biden officials from Jake Sullivan to Janet Yellen have emphasized that the world can and should follow the US in its new passion for productivism. Food and energy import bills are not only a climate problem, they point out, but a security concern. Indeed, nearly every import is increasingly scrutinized through a security lens, down to Chinese garlic.

The vision, then, is for localized, manufacturing-led green growth, erring on the side of redundancy rather than just-in-time production. All countries, the story goes, should be able to achieve prosperity through derisking, paired with local content restrictions, higher taxes, and subsidies for key sectors like clean energy, biotech and digital infrastructure.

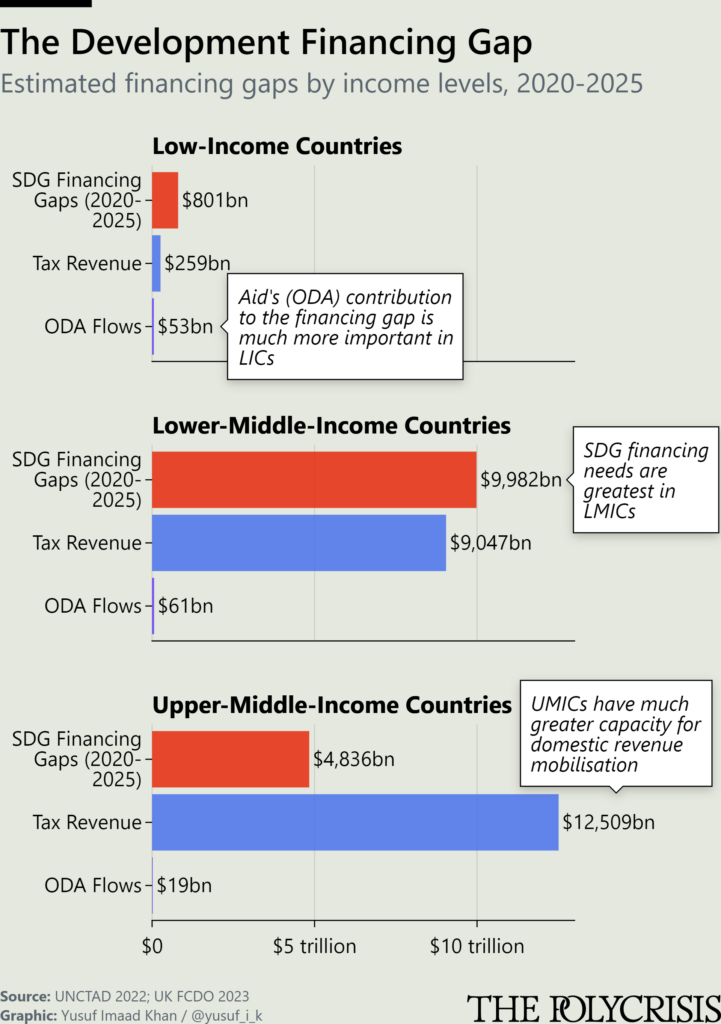

There is only one small problem. After overhauling its internal investment regime, the US has thwarted any meaningful structural changes to the global financial architecture. On IMF quotas, voting shares, taxation, and even on its measly contribution to the new Loss and Damage Fund, the US has been conservative and isolationist. There have been a few consolation prizes—Barbados’s PM Mia Mottley won debt payment pauses for natural disasters; the IMF will give slightly more interest-free loans to low-income countries—but, on the whole, the global financial safety net continues to ensnare, rather than rescue, the most vulnerable countries.

For every $1 the IMF provides to poor countries for social spending, it demands $4 in cuts in public spending. Countries do everything they can to delay and avoid bailouts since, when they come, they reduce domestic policy space and autonomy, and force countries to choose between debt repayments, social spending and climate.

The situation is not entirely hopeless. Norway, which has historically acted as a mediator between the North and South, has made $150 billion in oil and gas profits from the Ukraine war. Like the UAE, it may rechannel some of this windfall to underwrite the risk of green investments in developing countries. But we are far from seeing any coordination that could rival even the New International Economic Order of the 1970s—let alone the kind of South–South solidarity needed to tackle the climate crisis.

War

The past two years have seen more violent conflict than at any time since the end of World War II, according to the Uppsala conflict data program. Conflicts have broken out in many continents. In Africa, there have been over half a dozen coups, with combat fighting in the Congo and Sudan, and now a teetering cease-fire in Ethiopia. In the Middle East, Israel’s assault on Gaza threatens to expand into a regional war. In Europe, Russia’s brutal war of attrition in Ukraine has strikingly altered the political scene. After months of European and US support for its ally, including aggressive sanctions, the US Congress is left in a deadlock on the question of funding Ukraine’s resistance. The result in a multipolar world? Russia’s economy has been decoupled from Europe’s but thanks to its trade with countries in the East and South, its treasury remains flush with cash. We wrote about how the EU is preparing for Ukraine’s accession, and the all important question of who will pay to reconstruct the country?

On October 7 2022, the US launched an economic war against China. Biden issued a sweeping set of export controls aimed at restraining Chinese military modernization efforts by controlling advanced AI chips made with US inputs. The chips embargo was buttressed by the Pentagon’s largest ever military spending bill—$840 billion—with nary a murmur from inflation hawks. New US bases to be built in the Philippines and Papua New Guinea further cemented Beijing’s view that the US plans to encircle it and prevent its future growth. The panic about an impending war that set the tone during the first half of 2023 soon subsided with a series of crisis stabilization cabinet-level meetings and a constructive meeting between Biden and Xi in San Francisco in November.

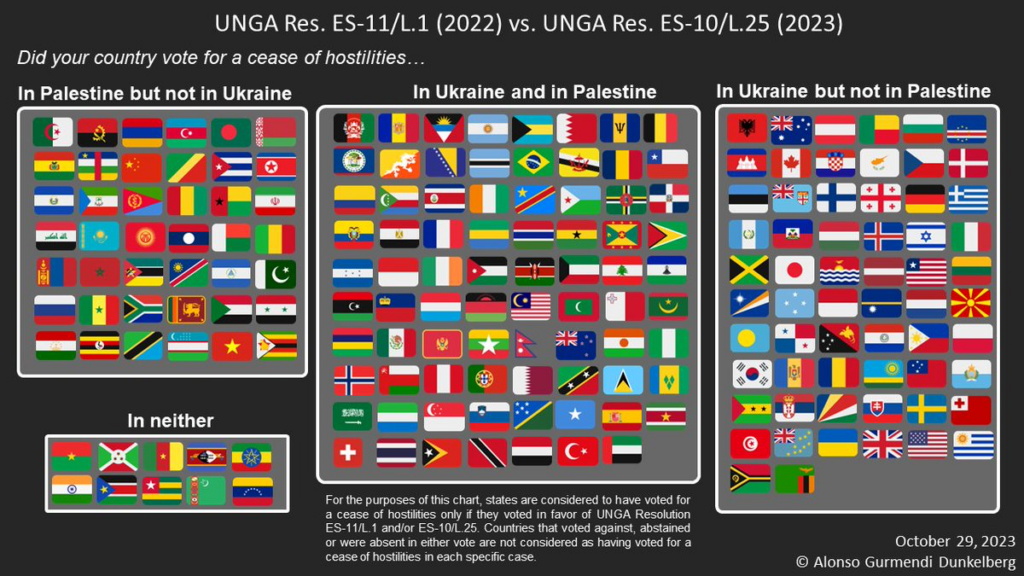

In the present context of a dangerous and differentiated world system, categories like “global South” and “global North” may no longer work. This is because, as Patrick Porter has argued, the global South isn’t simply comprised of “aggrieved cultures,” victims bearing wounds, but of ruthlessly self-interested nation states—much like those in the global North. Paying attention to regional actors and their rivalries and partnerships is key. Countries in the South are split on calling for a ceasefire in Ukraine and Palestine. For example, Brazil has called for a ceasefire in both cases, India in neither; Bangladesh and South Africa for a ceasefire in Palestine only; the Pacific Islands in Ukraine but not Palestine.

Labor

Around the world, workers are striking in a way not seen in decades. Betrayed by the US Congress in the IRA legislation, unions across America are taking it upon themselves to make the EV transition good for workers. A dispute between the US and the EU last year over the IRA meant that union-made cars did not get fatter subsidies. The United Auto Workers have fought back in an escalating series of strikes led by Shawn Fain in the US and Marie Nilsson—head of IF Metall, Sweden’s largest industrial union—has led a similar fight among Nordic unions fighting against Tesla.

Trade defiance

For most of 2023, it seemed that free trade had given way to “friend-shoring,” largely on grounds of national security. Predictions of a crackup in global trade patterns abounded. New policies on export controls, visa bans, investment blocks, and sanctions are now redirecting the flow of goods and people. We dug into the narrative to find that 2023 has seen an all-time high of goods traded across borders. Even bilateral trade between China and the US was at a record high of $400 billion in 2022. Firms are responding to geopolitical crackup by diversifying their supply chains into new countries. Bloomberg analysts identified which countries benefited—Indonesia, Mexico, Morocco, Poland, Vietnam—to which we added India and Australia.

Assessing and Looking Forward

What we got right and wrong

- US policy elites underrated the seriousness of chips export controls—we expected these would provoke a furious response from Beijing and US allies in East Asia and Europe. By the year’s end, US policymakers’ decoupling rhetoric softened into “derisking.”

- We expected a wave of debt defaults with record high interest rates, but only saw a few. Why? Commodity exporting countries showed surprising resilience as they earned higher dollar revenues.

- We anticipated a geopolitical crisis in Asia with Chinese aggression. This didn’t happen. There were lots of military flashpoints but only a North Korean rocket scare in Seoul—part of North Korea’s record year of weapons testing—plus some skirmishes in the Himalayas and in the South China Seas.

- We expected greater coordination among BRICS countries. We got this half-right. We’re seeing BRICS prioritizing local currency settlements and boosting African trade and investment. A troika of India, South Africa, and Brazil are leading reform of the Bretton Woods institutions during their G20 presidencies. Here, it remains to be seen whether the developing world will achieve the greater autonomy and coordination it aims for, or remain fragmented. Either way, one should have no illusions about the radicalism of a new non-aligned movement. The ruling elites of these countries are rarely concerned with carving out more policy space and autonomy for their publics. As William Shoki tartly put it, BRICS is only ever the anti-imperialism of the ruling class.

The year ahead

There are forty national elections slated for next year, the effects of which will cover 41 percent of the world’s population, in countries representing 42 percent of global GDP. These votes also represent approximately the same percentage of global emissions, with fossil-fuel industry interests well-represented.

We anticipate an anti-incumbency wave of world leaders over the next twelve months as voters elect heads of state in Mexico, South Africa, Russia, UK, US, India, Indonesia. Even a single election—Argentines have just elected libertarian dollarizer Javier Millei—has global consequences. Alongside nations, the European parliament and a host of other representative bodies are also going to the polls. Population movements may complicate polling predictions in several elections, given that the UNHCR anticipates that up to 130 million people will be displaced and in need of protection in 2024.

Lula will occupy center stage in 2024 as Brazil takes on the global reform agenda in its G20 presidency. Frustration with the US and Europe’s so-called green protectionism may frame the G20 and BRICS meetings. Lula may well amplify the anger expressed by many global South nations at this month’s climate summit, especially when Brazil hosts COP30 in 2025. Since China and India have already threatened to make formal complaints about EU’s carbon border adjustment mechanism, Lula’s intervention could be key at the WTO.

Barbados PM Mia Mottley’ successful advocacy of climate resilient debt clauses has raised hopes for a more systematic rethink of the G20’s Common Framework on debt resolution. It is creaking and may soon be replaced given Zambia’s public creditors, including China, just “derailed” a deal brokered with private creditors under the Framework.

These issues may transform 2024 from the year of elections into the year of finance. British Foreign Minister David Cameron has flagged a return to treating Aid as a mechanism to lever-in more private cash. This will rely on new mechanisms and private finance’s willingness and ability to meet the gaps. Recapitalisation of multilateral development banks, new SDR issuance, or a New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG)—a major theme to-be for next year’s UN climate summit in Baku—will be the focus of discussions.

We end at sea. Houthi rebels are poised to seriously disrupt the global economy with their actions in the Red Sea, in solidarity with Gaza’s besieged population, forcing ships to re-route around Africa. Meanwhile, thanks to drought, cargo ships in the Panama Canal are now stuck, holding up another major trade passage. Unlike the rather comical scenes of that large boat wedged in the Suez Canal in 2021, images from Panama fail to raise even a chuckle. We’re no longer dealing with the errors of a single human being, but with the tragic collective error of burning such vast amounts of fossil fuels, long after we should have stopped.

Filed Under